“Only 16% of the Board’s eligibility decisions fully reversed the eligibility rejections, and none of the other 84% of the applications have been allowed despite the effort and the expense of the appeal.”

Approximately two years ago, the Supreme Court’s issuance of Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank[i] changed the world of prosecution. The decision led to a stark decrease in allowances of patent applicants across industries as diverse as software to biotechnology.[ii] Applicants stuck in the post-Alice purgatory have had several prosecution options:

- Abandon their application;

- Attempt to wait out the Alice effects, in hopes that a new Federal-Circuit or Supreme-Court decision would change the current eligibility stance of an art unit or examiner; or

- Appeal a rejection.

Past reports have indicated that the reduced-allowance effect of Alice is not consistent across biotechnology art units[iii] or across computer-related art units[iv] Potentially, this art-unit variability suggests that some of the “harsher” art units are issuing erroneous eligibility rejections and that appealing the rejection would lead to favorable results. [v]

Only recently has the Patent and Trademark Appeals Board (PTAB) begun to issue decisions on appeals with appeal briefs filed after the Alice decision. We requested that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) identify each published application (and the art unit for which the application was assigned) for which: (1) an appeal brief was filed since September 1, 2014 (a date on which we estimated that Alice would have been considered by the applicant or representative) and (2) a PTAB decision was issued. As of July 12, 2016, 162 PTAB decisions met these criteria.

Over Half of PTAB Decisions on Post-Alice Appeals Fully Affirm Rejections

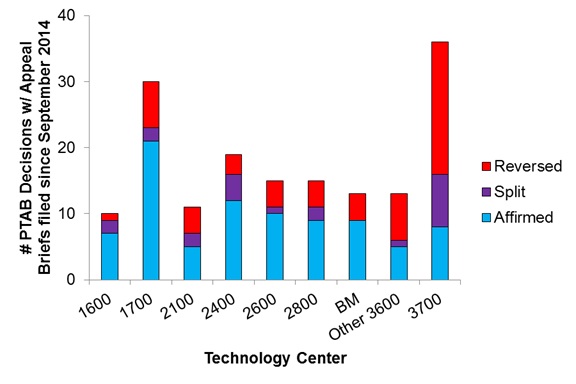

Overall, the PTAB affirmed or affirmed-in-part two-thirds of the appeals, 53% of which being affirmed in full and 14% being affirmed in part. As shown in FIG. 1, the lowest affirmance rate was observed in Technology Center 3700 (which examines applications corresponding to industries such as manufacturing, medical devices, mechanical engineering and education), where only 22% of the appeals were fully affirmed. Meanwhile, approximately 70% of appeals in each of Technology Center 1600 (Biotechnology and Organic Chemistry), Technology Center 1700 ( Chemical and Materials Engineering) and the business-method “BM” art units (3621-29 and 3681-96) were fully affirmed.

FIG. 1. PTAB decisions per technology center. PTAB decisions corresponding to appeals with Appeal Briefs filed since September 1, 2014 were analyzed to associate overall PTAB decisions with technology centers. Technology center 3600 was divided in business-method (“BM”) art units (art units 3620-29 and 3680-96) and other art units in the center (“Other 3600”).

Few PTAB Decisions on Post-Alice Appeals have involved Patent-Eligibility Rejections

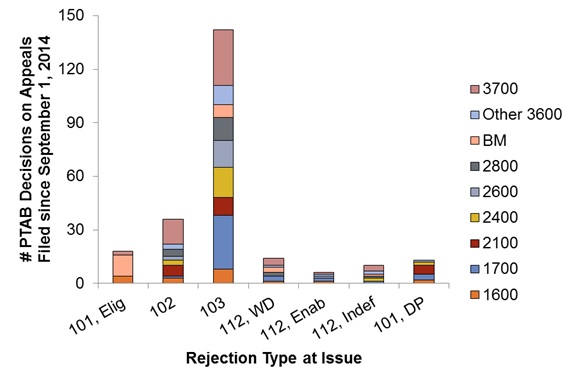

We manually reviewed each decision to identify each particular type of rejection at issue in the appeal and the decision types of the PTAB corresponding to each particular rejection. Specifically, we determined whether the appeal involved any of the following issues: patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 (“101, Elig”), anticipation under 35 U.S.C. § 102 (“102”), obviousness under 35 U.S.C. § 103 (“103”), written description under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) (“112, WD”), enablement under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) (“112, Enab”), indefiniteness under 35 U.S.C. § 112(b) (“112, Indef”) or double patenting under 35 U.S.C. § 101 (“101, DP”). For each of these issues, we determined whether a rejection was affirmed, reversed, affirmed with respect to a portion of the rejection or claims (“split”) or whether the PTAB had issued a new rejection on these grounds.

The most common type of rejection at issue in the appeals was obviousness. (See FIG. 2.) Meanwhile, only 18 appeals involved patent eligibility, which is perhaps surprising given the recent turmoil in this space. Of the eligibility appeals, 12 (66%) were from a business-method art unit.

FIG. 2. Types of decisions appealed from different Technology Centers. PTAB decisions were analyzed to identify which types of rejections were of issue. The plot shows the number of appeals from each Technology Center (dividing Technology Center 3600 as described in the legend of FIG. 1) that involved each rejection type.

The PTAB has Predominately Affirmed Eligibility Rejections Challenged in Post-Alice Appeals

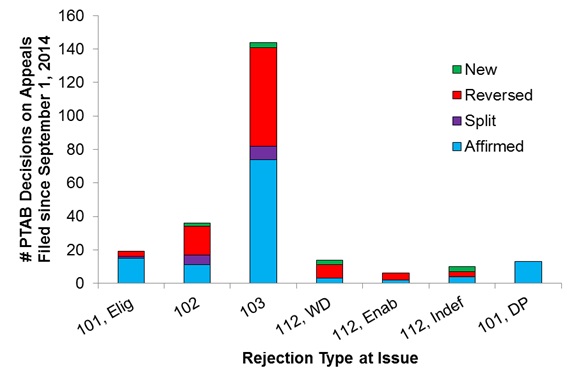

Appeals of rejections involving § 101 were unlikely to be successful, with 79% of patent-eligibility rejections (15 of 19 appeals) being affirmed. (See FIG. 3.) Specific data on each of these appeals involving an eligibility are shown below in the Table. The Appeal Briefs filed in appeals where at least one 101 rejection differed markedly, in terms of an extensiveness of argument, cases cited and whether extrinsic evidence (e.g., a Declaration) was submitted.

FIG. 3. PTAB decisions per rejection types. PTAB decisions were analyzed to identify which types of rejections were of issue and the decision corresponding to each decision type. A “split” decision may indicate that a rejection corresponding to some (but not all) claims were affirmed or that a different decision was reached with respect to different rejections (e.g., corresponding to same or different claims) of a same type.

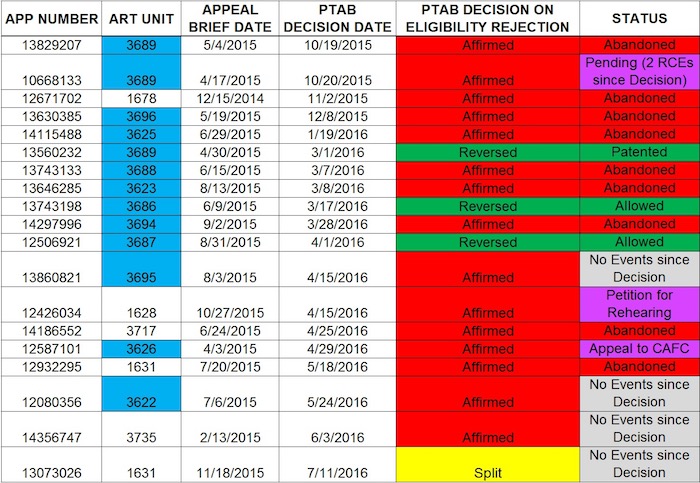

TABLE. Application data for post-Alice appeals with PTAB decisions rendered for eligibility rejections. Data is defined by column headings. Business-method art units are highlighted in blue. We highlighted the “Status” cells in purple for applications where the applicant has engaged in prosecution following a PTAB affirmance decision.

The high affirmance rate of eligibility rejections does not reflect an overall Board-affirmance tendency. The Board was substantially more likely to reverse other types of rejections. For example, with respect to prior-art rejections, only 32% of anticipation rejections were fully affirmed, and 52% of obviousness rejections were fully affirmed. Five years ago, it was reported that rejections under § 112 and in Technology Center 1600 were the most likely to be reversed.[vi] Our data supports that same result with respect to § 112(a) rejections today. Specifically, only 27% of written-description rejections and 33% of enablement rejections were affirmed.

The PTAB eligibility decision is highly predictive of the current status of the applications: For each of the three appeals for which the eligibility decision was reversed, the application was allowed immediately after the Decision (meaning with no intervening office actions). Meanwhile, amongst the applications corresponding to the fifteen appeals with affirmances of eligibility rejections, none have been allowed.

Conclusions

Does this data mean that it is unwise to appeal a patent-eligibility rejection? The authors feel as though, unfortunately, this is yet to be clearly determined. The sample size is small with only 19 decisions having been issued by the PTAB to address arguments corresponding to patent eligibility presented after the Alice holding. Further, amongst the appeals involving patent-eligibility rejections, the most recently filed appeal brief was filed in November 2015. Thus, all of the appeal briefs and most of the PTAB decisions were filed prior to the development of more recent case law that has further illustrated why and how various software technologies can be patent eligible.[vii] Further, most of the eligibility-involved PTAB decisions were issued prior to these recent cases, which may further have disadvantaged the appellants. Continued assessment of PTAB decisions on post-Alice appeals will provide further insight as to the Board’s interpretation of this area of law fraught with uncertainty and applicant frustration.

However, despite the small sample size, the fact remains that only 16% of the Board’s eligibility decisions fully reversed the eligibility rejections, and none of the other 84% of the applications have been allowed despite the effort and the expense of the appeal. While appeals can be an attractive mechanism by which to present arguments to a new decision-maker, an applicant should be aware that the statistical tendency of the PTAB “decision-maker” may no longer seem so attractive in the land of § 101 rejections, and that this gamble may not be worth the cost unless the applicant is equipped with very strong arguments.

__________

[i] Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l., 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

[ii] Gaudry, Grab & McKeon, Trends in Subject Matter Eligibility for Biotechnology Inventions, IPWatchdog (July 12, 2015 ); Kate Gaudry, Post-Alice, Allowances are a Rare Sighting in Business-Method Art Units, IPWatchdog (Dec. 16, 2014).

[iii] McKeon, supra.

[iv] Gaudry, supra.

[v] Gaudry, supra.

[vi] Kate Gaudry and Joseph Mallon, Appeals and RCEs – the Frequency and Success of Challenges to Specific Rejection Types, Intellectual Property Today (Nov. 2011).

[vii] See Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2016); See also BASCOM Global Internet Servs. v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 11687 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

17 comments so far.

Eric

August 8, 2016 02:19 amThe comments so far seem to miss the point. If the applicant has a case where the examiner has a <20% allowance rate and the appeal success rate is 21%, then, to efficiently use presumably limited resources, the applicant and his/her attorney should be weighing the potential value of the case against the likelihood of success and the cost of appeal, taking into account any value-reducing limitations that were added to reach the still low success rate. Regardless of the path chosen, you cannot make an informed decision without statistics such as these. Either way, you're guessing, but I'd rather make a data-driven guess than an ego-driven guess.

Anon

August 4, 2016 07:38 pmTJM,

I expressly decline your invitation to compare only to the UTSA.

As you well know, you need to actually use controlling state law and not the UTSA. You must take the state by state differences into account.

As to any effect from the AIA being one of “marginally” – well, I would again disagree with you, and point out that the AIA is anything but marginal in its very widespread effects on weakening patents. Clearly, the time to obtain, the solidity of what is obtained and the risks are far greater than prior to the AIA.

With apologies for the snark, I have serious qualms about you having serious qualms, because you seem to be in a different reality than the one that I am in.

As to Alice – and nay combined effect – I still do not understand why you are so reticent for acknowledging what it clearly one of the largest shifts ever in the balance between trade secrets and patents. Yes, the limits and risk of TS protection – at the state level – have not changed (for argument’s sake, I grant you the individual state level – but you still neglect the Federal level implications). But you simply cannot look at that item in a vacuum (as you apparently are).

TJM

August 4, 2016 11:16 amAnon,

Sorry, I thought I was clear that I wasn’t asking for a comparison of the federal act to any given state, just to the UTSA. I realize that states have enacted their own modifications to the UTSA, but I would appreciate even one meaningful difference between the DTSA and the UTSA. Honestly, I am not trying to be snarky, I am just not aware of any.

I agree that the AIA marginally increased the incentive for TS against patent, but I think this is an overstatement on your end. The PUR exception is very narrow. Also, the PTO has interpreted the AIA as overruling the Metallizing Engineering case, but it is not clear at all if courts will agree with that interpretation. There is significant uncertainty surrounding these aspects of the AIA, and I would have serious qualms about relying on them as the basis for advocating TS protection instead of filing a patent.

Of the three things you mentioned, the Alice decision has done the most damage to the value of patents. But I still disagree that this will encourage innovators to run to TS. Most of the time that I talk to a client who has a software invention (for example), I discuss Alice. This causes the inventor to wonder if it would be better to protect it as a trade secret. Then, I ask the inventor how easy would it be to reverse engineer the code. In a few cases, it would be very difficult, and TS is the best approach. However, in most cases, it is not incredibly difficult and the TS protection would be severely limited. In these latter cases, the inventor comes back around to filing a patent application. The DTSA hasn’t significantly changed this calculus, because the case law with respect to reverse engineering has not changed. If a product can be reverse engineered, the manufacturer should take little comfort in TS protection. As I understand you, your point is that maybe Alice/AIA/DTSA make it more likely that an inventor will take his chances with TS protection. I think that is doubtful because the limits of TS protection have not changed.

Anon

August 4, 2016 08:49 amWhile “bring a halt” might be a little hyperbole, there can be no doubt that the ongoing changes and trade-offs of a weaker patent system for a stronger trade secret regime does work against the very purpose of the patent system (the quid pro quo of sharing for a limited time right).

As I said though, part of my role as client advocate is to advise my client of the best way forward in the evolving legal scheme. TJM’s views aside, there should be no doubt that the landscape has in fact been changing.

Night Writer

August 3, 2016 09:57 pm@2 Anon: The “evident” better path is the path of Trade Secrets.

I would like to see an accounting of this and the likes of people like Lemley answer for this happening. Trade secrets will bring to a halt innovation and bring to a halt the freedom of movement of employees as long as wage gains.

Anon

August 3, 2016 05:31 pmTJM,

Thanks for the dialogue. To the point of comparing/contrasting the Federal action and any one particular state, I will pass as this is more work (for a blog) than I am willing to do at this point.

However – the fact that it is more work than I care to do is an indicator that for any size corporation involved in more than one state, the new Federal action is something that simply cannot be presumed to be the same as that state’s version of the UTSA.

As to your uncertainty over my thrust of “burgeoning new realities,” let me simply state that the “always been an incentive” is very much NOT static. That’s the point that I have been making all along. Compare the non-static patent field (lower protections mean more interest in trade secrets), the changes in the AIA (the expanded PUR means more interest in trade secrets), and the New Federal cause of action (as mentioned – not contrasting with any one state – but the fact of the matter is that this may mean that a former state limitation may no longer be a limitation – the new Federal cause of action is a Federal action and not a state action). The incentives are very much not still the same.

All of this is of course over and beyond just “keeping up with what it takes to maintain a trade secret.” I think that you are viewing that aspect and presuming that that aspect may be more or less static.

TJM

August 3, 2016 02:12 pmAnon,

A quick follow up: obviously, when I ask about your thoughts on the differences between the federal TS act and the UTSA, I would appreciate it if you would provide specific examples. Not necessarily citations to the statute, but just concepts or topics in the statute that are materially better/different from the UTSA,

TJM

August 3, 2016 02:10 pmAnon,

Your comment about re-reading the statute is well-taken, and is fair. It’s been a couple of months since I read the federal statute, so it wouldn’t hurt to review it again. However, I would appreciate your thoughts on the ways that you believe the federal statute is different (in a meaningful way) from the UTSA. Even though states have variations in their implementation, I don’t put much stock in the value of simply having an additional federal cause of action. Beside, in a lot of ways, there has been a federal cause of action since the mid-90s under the Economic Espionage Act.

Also, I don’t understand what you mean about “burgeoning new realities” that providing a new federal cause of action will somehow lead to less reverse engineering, or somehow make it more difficult. There has always been an incentive to build products that are difficult to be reverse-engineered – that incentive has not changed. The problem is that a manufacturer who does not continually update its security to stay ahead of the curve can suddenly realize (too late) that it was not taking reasonable steps to keep the information secret. At that point, any protection under the trade secret act is gone. Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon fact pattern for plaintiffs in trade secret cases; they think they have their information locked up tight, but they don’t update their security measures to match technological progress.

I fail to see how the new statute suddenly changes anything about the economic environment. The incentives on each side are still the same.

Anon

August 3, 2016 12:57 pmTJM,

I take issue with all of your points presented.

Yes, I was referring to the new Federal law, and I would recommend that you re-read that law if you think this is nothing more than what is already available per the USTA. By itself, having a new – and additional – Federal charge sidesteps many of the differing State versions, wherein each State did what it wanted to do.

Your comment in regards to reverse engineering is also not in accord with the burgeoning new realities that new and additional protections for Trade Secrets will prompt a trend in the opposite direction. You take a mere one-sided view that tools to crack (existing) protections will become cheaper and totally neglect that the economic incentive has changed and that incentive is to build MORE – and more difficult to crack – NON-easily reversed mechanisms.

Your “assumed” easier state is the opposite of the changed economic environment. You act as if the environment has not changed.

Your assessments that support your conclusory statements need to be recalibrated.

TJM

August 3, 2016 09:56 amAnon,

Are you referring to the recently enacted federal trade secrets act? While it may be true that the federal government has a refreshed commitment to protecting trade secrets, there isn’t that much in the statute that is new compared to the UTSA. Also, my comment was referring to reverse engineering. Generally, if something can be easily reverse-engineered (i.e., if the reverse engineering process is not unreasonable or cost prohibitive), there is no trade secret protection. As technology improves, it is likely that the tools for reverse engineering a product and its software will become cheaper, which will severely undercut any argument that the product is protected as a trade secret. So no, I do not expect it to become much more difficult, and I do not trust the passage of a token federal statute to change that expectation, much less a statute that mostly parrots the law that already exists in every state in the country.

Anon

August 3, 2016 06:50 amTJM,

What you point out as a weakness is indeed a weakness. But you jump the gun with your conclusory “becoming much more easy.”

This has yet to unfold because we are early in the cycle of trade secrets gaining legal strength. You should expect the opposite: “becoming much more difficult.”

TJM

August 3, 2016 01:37 amThe problem with trade secret protection is that it has zero value if the product/algorithm can be reverse-engineered, which is becoming much more easy. I agree that it should be in the conversation, but it is often a non-starter for my clients because it is usually possible to reverse engineer.

Anon

August 2, 2016 06:12 pm“Unavailable” should read “unavoidable”

Anon

August 2, 2016 02:56 pmThe path would be in place of actually filing in the first place.

My apologies for not making that clear.

Once filed (and then being confronted with the rejection) as here, I do NOT have a “better path.”

“Lay down and die” is not a great choice and is only advisable if “death” is unavailable and laying down sooner makes more economic (or other driver) sense for the client.

(My apologies as my alternative is a bit of a non sequitur to your point, occurring as it does too late for my path offered)

Curious

August 2, 2016 01:50 pmCoupled with the AIA PUR, the trade secret path needs to be in every conversation with clients when IP is being discussed.

As I’m sure you know, that path is not available once the rejection has been issued. Almost all applications are published, and most are published before a first office action.

As to trade secrets in general, while (in theory) that should protect certain types of intellectual property, I think the amount of IP protectable as a trade secret is very limited. Unless you have a formula/process that cannot be reversed-engineered, you are pretty much out of luck.

Anon

August 2, 2016 11:05 amCurious,

The “evident” better path is the path of Trade Secrets.

Coupled with the AIA PUR, the trade secret path needs to be in every conversation with clients when IP is being discussed.

This seemingly “capitulation” is simply a pragmatic view of the “legal reality” we are currently living with, and is NOT without its share of pain to my personal views of how a strong patent system is key to long term innovation.***

This also should be coupled with as restrictive as possible employment agreements, with a definite eye (for those with employees in the more “employee-friendly” states towards the NEW and additional Federal causes of action now available.

***sometimes being the “Devil’s Advocate” does mean that I have to “play with fire”…

Curious

August 2, 2016 08:01 amWhile appeals can be an attractive mechanism by which to present arguments to a new decision-maker, an applicant should be aware that the statistical tendency of the PTAB “decision-maker” may no longer seem so attractive in the land of § 101 rejections, and that this gamble may not be worth the cost unless the applicant is equipped with very strong arguments.

What other choice do you have? Examiners routinely ignore limitations, already in the claims, that should take a claim out of the realm of “an abstract idea” so amending claims rarely work.

Unless you are OK abandoning the application, you appeal and see whether sanity is restored in the 3-4 years it takes to get a Decision. If you have a better option, I want to hear it.