In the past decade, economic growth, wage growth, business investment and productivity growth have declined dramatically. Economists have discovered that productivity growth alone explains the dramatic development of industrial economies. Yet, the causes of productivity growth are unclear, with capital, labor and technological contributions.

In the past decade, economic growth, wage growth, business investment and productivity growth have declined dramatically. Economists have discovered that productivity growth alone explains the dramatic development of industrial economies. Yet, the causes of productivity growth are unclear, with capital, labor and technological contributions.

Economists offer a number of theories involving exogenous growth theory, endogenous growth theory and evolutionary growth theory to explain the phenomenon of productivity growth and its centrality to economic development.

The essential ingredient of productivity growth is total factor productivity (TFP), which represents an intangible collection of intellectual human attributes that we designate as technology innovation. Macroeconomic theories, however, fail to adequately represent the source and mechanisms of the decline in productivity growth and in TFP in recent years.

The present article suggests that there are two main sources of the dramatic declines in productivity growth and TFP in the past decade. First, the U.S. patent system has been substantially degraded. Second, the competitive configuration of the technology industry has become highly concentrated. The combination of the reduced competition from the oligopolous configuration of technology incumbents with reduced patent rights for market entrants shows a mechanism for the decline in investment in innovative R&D that has been the engine for economic growth for hundreds of years.

The patent system has been attacked by radicals on the left and the right. On the right, incumbents seek to protect monopoly profits. On the left, progressives attack the property right in a patent in order to seek a public interest benefit to innovation research. As these critiques have influenced patent policy, patent law has been cabined into a narrow scope which only benefits wealthy companies through dramatic increases in enforcement transaction costs.

In a weak patent regime, there is limited enforcement of patent rights. For instance, large technology incumbents may engage in efficient infringement in which they infringe others’ technologies until they are caught, typically many years later, and then only pay a nominal fee that they otherwise would pay if they negotiated a license. Without strong patent enforcement, there is no incentive to invest in innovation, either by incumbents that can infringe with impunity or by market entrants that cannot reasonably enforce their patent rights.

The weak patent system, combined with the oligopolous technology market configuration, explains the declining investment in technology R&D even as technology incumbents realize record profits and enjoy historic cash hoards.

These policy factors explain the recent dramatic drop in productivity growth, the slowest economic recovery in about a hundred years, slow wage growth, weak business investment and the general discontent that is shaping politics.

If the causes of weak productivity growth involve government policies – patent policy and competition policy – we can modify the policies to restore growth. In many cases, these policy prescriptions are simple to implement and may provide dramatic catalyst for economic growth.

Economic Data and Background

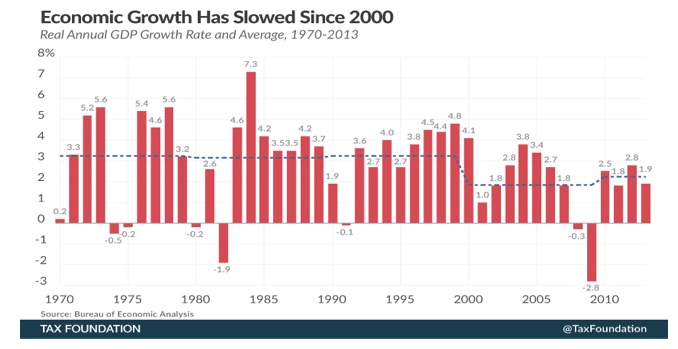

Economic growth in the U.S. and in the world economies has been anemic from 2010 to 2016. U.S. economic growth in the six years from the end of the recession (2009) has averaged about 2 percent annually, the lowest long-term economic growth since WWII.

Chart I: Real Annual GDP Growth Rate and Average, 1970-2013

While the Great Recession and the Global Financial Crisis were complex economic disruptions, the data on economic growth immediately before the recession was also not robust. The economies of the U.S., Japan and Europe all appear to be experiencing secular stagnation, with neither significant growth nor significant decline in output.[1]

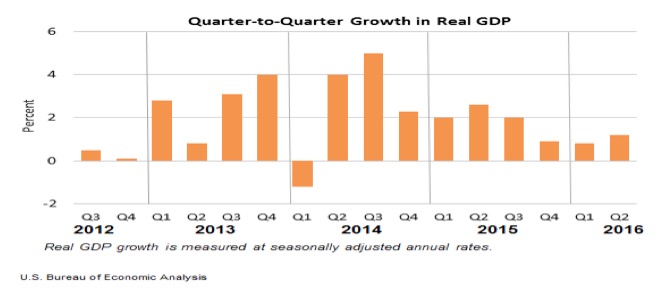

Chart II: Quarterly Growth in GDP, 2012-2016

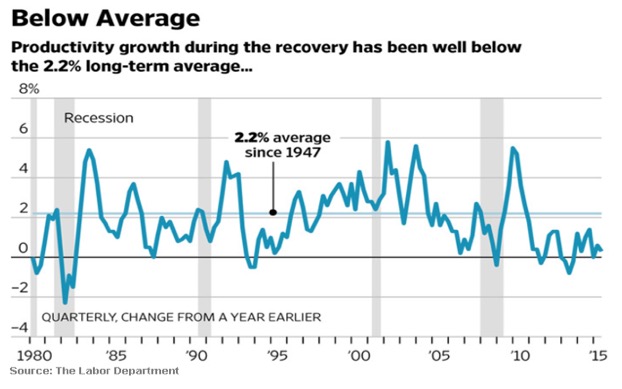

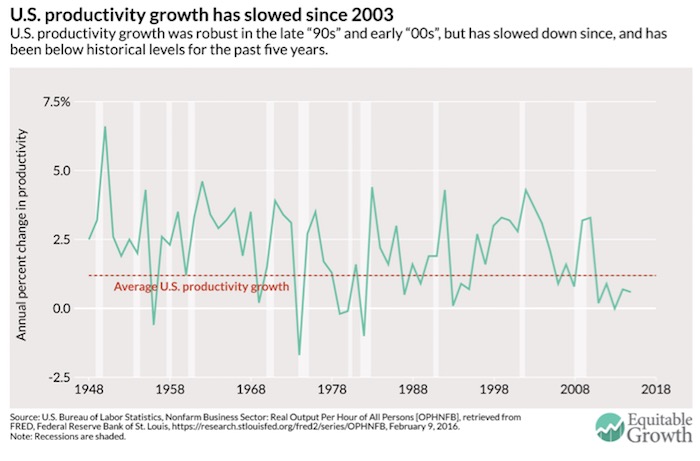

A consensus view believes that a key source of the mediocre economic growth data lies in the trend for productivity growth. In the period after the recovery, productivity growth data show a clear pattern of decline. Productivity growth declines are near zero in 2016 after very poor showings of less than 1% growth from 2010 to the present.

There has been little precedence for the decline to zero, or negative, for productivity growth data for several generations. Specifically, productivity growth has been under 1% for six years and appears to be falling. Many economists point to productivity growth declines as a main source of anemic economic growth.

Chart IV: U.S. Productivity Growth Trends, 1948-2016

Federal Reserve Chairwoman Yellen indicated alarm at the poor productivity growth data in a June, 2016, speech:

“Over time, productivity growth is the key determinant of improvements in living standards, supporting higher pay for workers without increased costs for employers. Recent weak productivity growth likely helps account for the disappointing pace of wage gains during this economic expansion. Therefore, understanding whether, and by how much, productivity growth will pick up is a crucial part of the economic outlook.”

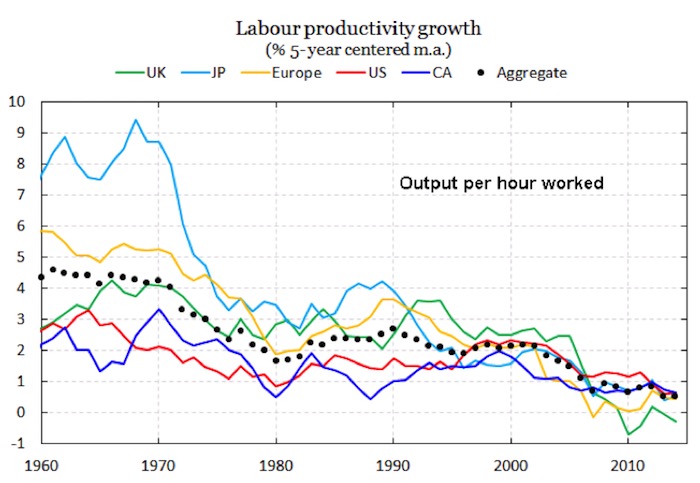

The productivity growth problem also appears to have international aspects, with major industrial nations experiencing synchronized productivity growth decline trends in the past decade.

Chart V: Labor Productivity Growth of Industrial Nations, 1960-2015

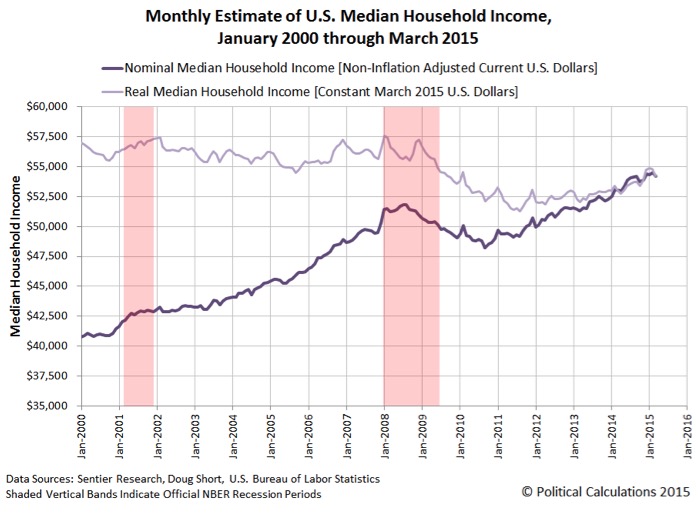

Increased productivity growth yields enhanced wages in the long-run. Like productivity growth, real wage growth has been anemic, little changed since the late 1990s, indicating a structural economic malaise. Because wages have stagnated, overall consumer demand has been slack, which explains the soft demand for commodities as reflected in weak commodity prices. There appears to be a causal link between productivity growth declines and wage growth stagnation.

Similarly, the effects of positive productivity growth can be disruptive as work is increasingly automated and employment growth is limited; consequently, technology adoption causes increased productivity of existing labor as well as layoffs since more work can be performed by fewer employees. While the official unemployment rate has been restored to historic norms, the unusually low labor force participation rate of 62.6% distorts these labor data.

Chart VI: Monthly Estimate of U.S. Median Household Income, 2000-2015

In addition to wage stagnation, business investment has also stagnated in the last six years. Economists dispute the causes of investment growth after the financial crisis. However, there is a clear pattern of decline in business investment that is related to productivity growth declines.

Economic theory clearly shows that productivity growth is the central source of aggregate economic growth, profit growth and wage growth.[2] Moreover, some economists argue that the decline in productivity began before the recession from 2007-2009, suggesting a deep structural problem.[3]

Connected to the observations of economic growth in the last forty years, and complicating causal explanations, is the recognition that productivity growth tends to spike after a recession. These productivity growth spikes are seen in 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2008. It appears that recessions force mass layoffs, which tend to enhance efficiency of surviving labor output per employee. However, in all cases, these post-recession productivity growth increases represent artificial temporary changes rather than long-term growth patterns, followed by periods of productivity weakness.

The effects of declines in productivity growth are substantial. From productivity growth declines flow slower aggregate economic growth, slower employment growth, slower wage growth and less aggregate wealth generation. Interestingly, with declining productivity growth, rising labor costs produce constrained profits for the same output. From poor productivity growth, then, wage increases are difficult without cutting into corporate profits.

If wage stagnation is attributable to productivity growth declines, consequences include enhanced social inequity. Consequences of declining productivity growth, then, include stagnant economic growth, stagnant wages, increased inequality, diminished quality of life, diminished demand for goods and voter angst.[4]

The productivity growth declines of recent years have been the subject of curiosity by a range of economists and journalists across the political spectrum.[5] Because of its centrality to economic development, economists have sought to explore the causes of productivity growth.

A New Theory of Patent System Degeneration as Explanation of Productivity Growth Decline

My central thesis is that productivity growth is strongly correlated with a strong patent system. Consequently, I will show that the attack on patent rights starting about 2005 is correlated to the decline of productivity growth. The crucial element of TFP preservation is an effective patent system. The patent system is designed to induce business investment in technology R&D. In effect, the macroeconomic analysis of productivity growth rests on microeconomic phenomena of decisions made by entrepreneurs to risk capital on technology projects in the expectation of a reward.[6]

The U.S. patent system is embedded in Art. I, section 8, clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution:

“Congress has the power . . . [t]o promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” This simple yet elegant sentence describes the core source of America’s power and explains its source of productivity growth.

The high correlation of a strong patent system with positive productivity growth in the 1980s and 1990s is well established as well as the correlation of a weak patent system of the 1970s to weak productivity growth.[7] The major factor in 1982 that separates the weak patent period of the 1970s to the strong patent period from 1982 to 2000 was the establishment of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit to adjudicate patent cases in a specialized court. Similarly, countries with a strong patent system, such as Germany, have a strong economy, while others, such as Japan, with a weak patent system, have economic stagnation.

The weakening of the patent system in the last decade explains the decline in productivity growth that originated before the recession. The present theory of productivity growth decline explains the reduction in business investment in R&D, the stagnation in wages, the reduction in business starts, the constrained competitive configuration of industries and the concentration of technology incumbents into the highest capitalized and most profitable companies in the world.

The central origins of the weakened patent system lie in political ideology on both the far left and the far right in which narrow anti-patent policies collide with microeconomic reality. Whereas the U.S. patent system represented the democratization of invention from 1790 to 2000, the relentless attacks on the patent system by ideologues on both the left and the right have resulted in an aristocratic patent system that locks out all but the wealthiest players.

One result of a weakened patent system is the concentration of technology industries yielding a competitive configuration of only a few market players with tremendous polarization between incumbents and market entrants. In combination with weak antitrust enforcement, a weak patent system provides the explanation for weak productivity growth, slow aggregate economic growth, limited business investment, and, ultimately, a reduced standard of living.

Without modifying the radical patent policy shifts of the last ten years, there is virtually no reason to expect an improvement in productivity growth in the future. And, since the U.S. is so central to productivity growth worldwide – the U.S. performs about half of R&D and supplies the engine for much of the world’s productivity growth – global economic growth will be atrophied as long as these policies are not substantially modified.

CLICK to CONTINUE READING: Up next will be discussion of the correlation between the U.S. patent system and productivity growth.

_______________

[1] Worse yet, the projected growth rate for the U.S. economy is expected to be below long-term averages for many years. The IMF projects a 2% growth rate for 2016-2021, the Economist Intelligence Unit projects 1 – 2.3% growth for 2016-2021 and the OECD Long-Term Forecast projects growth for 2016 to 2050 from 1.5 to 3%, with descending growth projected for each decade.

[2] There is an argument that as labor market demand increases, wages increase and that higher wages supply increased demand for goods, which stimulates productivity growth. The argument suggests that labor scarcity provides an incentive for businesses to invest in productivity enhancing machinery. However, the fallacy in the argument is the assumption that businesses invest in machinery as labor costs increase, which is false because investment in both higher wages and equipment cuts into profits. Tighter labor markets typically point to lower productivity growth. Instead, higher labor wages tend to stimulate outsourcing to preserve profits. Finally, when companies do replace workers with automation, wage growth is further reduced, illustrating the complex dynamics of productivity growth, capital investment, wage growth and profits.

[3] See Fernald, J., “Productivity and Potential Output Before, During and After the Great Recession,” 2014, showing that productivity growth declines started in 2005, not in 2010.

[4] The dramatic political consequences of slow economic growth and the stagnation of wage growth include the rise of populist movements on the left and the right.

[5] See Daniel, T. and D. Brown, “Missing the Juice: What’s Happening with U.S. Productivity Growth?” Third Way, March 1, 2016; Irwin, N., “Why is Productivity So Weak? Three Theories,” NYT, April 28, 2016; Jenkins, H., “Make America Grow Again,” WSJ, April 28, 2016; Fleming, S. and C. Giles, “U.S. Productivity Slips For First Time in Three Decades,” Financial Times, May 25, 2016; Pethokoukis, J., “U.S. Productivity Growth is Set to Fall for the First Time in Decades: Should We Worry a Little or a Lot,” American Enterprise Institute Ideas, May 26, 2016; Bartash, J., “U.S. Worker Productivity Sags Again in the First Quarter,” MarketWatch, June 7, 2016; Roubini, N., “Why This Golden Era of Innovation Isn’t Improving Productivity,” Bloomberg, June 7, 2016; A. Soergel, “The Productivity Paradox,” U.S. News and World Report,” June 1, 2016; Flowers, A., “The Fed is Worried About Worker Productivity,” FiveThirtyEight, June 15, 2016; Krugman, P., “Bull Market Blues,” NYT, July 15, 2016; Bunker, N., “Did the Great Recession Reduce U.S. Productivity Growth?,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, July 25, 2016; Morath, E., “Seven Years Later, Recovery Remains the Weakest of the Post-World War II Era,” WSJ, July 29, 2016; Review and Outlook, “Make America Grow Again,” WSJ, July 29, 2016; Samson, A., U.S. Economic Growth of 1.2% Misses Estimates,” Financial Times, July 29, 2016; Gramm, P. and M. Solon, “Why This Recovery is So Lousy,” WSJ, August 3, 2016; Irwin, N., “We’re in a Low-Growth World: How Did We Get Here?,” NYT, August 6, 2016; Gordon, R., “Can Clinton or Trump Recapture Robust American Growth?” NYT, August 8, 2016 and; Leubsdorf, B., “U.S. Productivity Growth Fell for the Third Straight Quarter,” WSJ, August 9, 2016.

[6] The patent system is paradigmatic of endogenous growth theory since it harnesses animal spirits. As Lincoln observed in the “Second Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions,” 1867: “Next came the Patent laws. These began in England in 1624; and, in this country, with the adoption of our constitution. Before then, any man might instantly use what another had invented; so that the inventor had no special advantage from his own invention. The patent system changed this; secured to the inventor, for a limited time, the exclusive use of his invention; and thereby added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius, in the discovery and production of new and useful things.” Interestingly, Lincoln was the only president that held a patent and thus was speaking from his own experience. Like Edison, he was also a non-practicing entity that sought to license, rather than manufacture, his invention.

[7] There was also industrial concentration in the 1980s and 1990s, caused by deregulation, even with high productivity growth from a high level of competition stimulated by a strong patent system. Thus, industry structure alone is not sufficient to explain productivity growth declines from 2006 to the present.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

28 comments so far.

Anon

October 3, 2016 06:56 pmToo late – for you.

Not sure where exactly you think that I have thin skin though. And the only ample absurdity and pretentiousness is what you are supplying. The “cause and correlation” sound byte is an old anti patent sound byte. Maybe you want to refresh your thoughtless additions to the discussion.

May I also suggest that the tactic of accusing others of that which describes your own actions is not a wise tactic to take.

CR

October 3, 2016 11:39 amAnon,

Your ample absurdity and pretentiousness contrast with the thinness of your skin, and so I’ll apply Twain’s advice:

Never argue with a fool, onlookers may not be able to tell the difference.

Anon

October 3, 2016 06:36 amCR,

Your point was not made – and if you are thanking me, then thank you for making MY point.

Your quip of “correlation is not causation” is an empty hackneyed phrase, so often wielded by someone without an appreciation of the issues under discussion.

I don’t think it takes a man to cause suffering through their ignorance, so you probably can smile all that you want, and that won’t help you change your ignorance, nor become a man.

CR

October 2, 2016 09:32 pmUmm…Thanks for making my point, i.e., the challenges go well beyond anything that can be addressed by changes to the patent system.

It takes a man to suffer ignorance and smile 🙂

Anon

October 2, 2016 06:18 pm“highly doubtful that such strengthening would be truly related,;’

And yet, even “correlation” IS a relation…

The lady doth protest too much, methinks.

CR

October 2, 2016 09:37 amAgree with those who would find the link simplistic. Correlation is not causation, and a host of similarly-trending figures/graphs would suggest other culprits. For example, our politics and the reduction in the effectiveness and approval rating of congress have similarly trended downward. This leads to uncertainty, polarization, and consigning realism for optimism (all which reduce investment). Also, academic performance levels of US students continue to fall–a critical problem for a country that would like to be a leader in innovation. Also, the ever-increasing divide in wage disparity erodes morale, the ‘American dream,’ and squeezes household budgets, resulting in fewer would-be customers being able to afford new innovative products, the purchases of which would feed-forward the cycle and economy.

Don’t get me wrong, I fully support a thoughtful strengthening of our patent system (and think Samsung should lose big at the SCOTUS), but find it highy, highly doubtful that such strengthening would be truly related, let alone a panacea, to the systemic economic challenges we face.

Anon

September 29, 2016 06:21 amPaul,

God has a better punishment system for transgressors.

(accountability is always an important factor in any set of system of rules)

Anon

September 29, 2016 06:19 amBenny,

Wrong on both accounts. I have worked in both engineering and management roles within R&D and production (scaling R&D into implementation).

Sorry, but your views on “restraint from increasing regulation on productivity” are bizarre and off kilter.

Paul Cole

September 29, 2016 05:44 amI am not convinced that weakening patent rights is the whole story, but it does not help with research, development and the underlying investment.

There is a tendency for the law to become more complex with time, and patent law both in the US and Europe has to some extent become a victim of this. Does the US REALLY need 390 sections to define a workable patent law. Memorably, towards the end of the First World War President Wilson set out 14 points, prompting the French President Clemenceau to remark that God himself needed only 10.

Benny

September 29, 2016 02:32 amAnon,

Never worked in R&D or production, right?

Shelley

September 29, 2016 01:55 amThe patent laws are changing almost constantly. Just 10 years ago it was not too hard for an individual or small business to get a utility patent. Today it is almost a nightmare to get one. Now many have stopped trying because of how difficult it is and instead just quickly create their product (overseas) and get it to market. Their product sells if they market it well etc.

The problem with that is, that product is not manufactured here. It may not even be sold in a store here. Maybe just online and do real well because they could afford to make so many for cheap instead of spending money on Uspto costs and attorney fees and mfg in USA.

So to sum it up, the losers in this game are:

1. The inventors that think it is best to have a patent, even though it does protect you, it can take so much time and money compared to the past

2. Our country is losing because items are getting made quickly and cheaply overseas. Also, even il items are patented, they are being copied by you know who. So we have less productivity in manufacturing – declining for years

There is way more to the overall decline productivity growth than this, which I have been seeing for 20 years as an industrial and supply engineer / consultant, understanding people and working directly with all staff levels.

I do agree that the use of high tech equipment, like robotics in distribution can make workers feel not needed and less motivated to work.

I believe in labor standards (for hourly pay work) where you are paid based on meeting and beating the standard work requirements.

Similar to how salesmen get bonuses for meeting or exceeding sales requirements.

Companies that use this have much higher productivity rates and happier workers and it grows.

There are systems for this and industrial engineers that put this together for companies.

Shelley Jordan

September 29, 2016 01:15 amGreat detailed article. I’m a industrial / supply chain engineer / consultant & inventor. I agree with you and have other solutions that I want to implement for our countries economy and low productivity growth, despite our messed up patent system. My plan to me is common sense given all my years helping so many companies, seeing all the changes and being with such a large variety of people (different working levels, classes, communities, education levels, races, backgrounds, beliefs, needs, pay, the list goes on). Supply chain covers so much including the people, productivity, data, technology, movement of anything, systems, operations, economics, finance, design and location of facilities, collaboration of businesses and their technology, inventory, etc. Overall, optimizing the situation for lowest costs / highest profit and the lives of the employees. Which is what business and our country are suppose to be about.

Anon

September 28, 2016 04:14 pmThose are non-sequiturs, Benny, as those are NOT regulations on productivity, let alone increasing regulations on such.

I would (easily) imagine UNsafe devices to have the opposite affect on productivity than what you are claiming.

You appear to be very confused on the role of regulations (and law) in society.

Benny

September 28, 2016 03:12 pmAnon,

Look at the power supply of your laptop and count the regulatory symbols, such as ce or gs. Go to one of these regulatory body websites and see how many revisions there are to each standard. Do a web search for the terms rohs, reach, weee, conflict minerals. Beginning to get the picture?

Anon

September 28, 2016 03:04 pmBenny,

To give you some (small) benefit of the doubt, do you have any examples of these “Increasing… regulation on productivity” items that you mention?

Lawrence Lockwood

September 28, 2016 02:02 pmExcellent article. An often overlooked factor is the ability of Congress or courts to change the rules during a patent’s life, such as ALICE. Why Congress doesn’t recognize the private property rights for the exclusive term and hold the patent to the laws in affect at the time that the patent was issued, i.e. grandfathering. This is common is many areas of property rights, but its a complete sham for an inventor to comply with all the regulations at the time his patent issues, only to find a few years later the rules have changed. It makes any investment of time or money in a patent so uncertain as to create an unforeseeable risk. In case you missed it, supporting arguments for your position.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/us-competitiveness-project-harvard-business-school-hbs-michael-porter-030021739.html?soc_src=mail&soc_trk=ma

Anon

September 28, 2016 12:19 pmStep back,

Plenty of blame to go around for that (including in a noteworthy manner, plenty of Ivy League academics who had been – knowingly or not – “captured” by those perpetrating the shenanigans).

step back

September 28, 2016 10:39 amEG @10

2008 was a melt down (implode) of the financial system itself, not merely of certain financial houses per se. It is the system in whole (and due to not enforcing regulations) that allowed for mortgage loans to them who could not pay and for off loading of liability in the form of deceptively rated derivatives.

Of course, as mud slinging apes we must “blame” a singled out sacrificial actor as we always do. 😉

EG

September 28, 2016 08:31 amHey SB,

Agreed that the issue is more complex than simply a strength of patent rights issue. But strength of patent rights (or in this case the weakening of them) is a reflection of the bigger issue of the friction (including burdensome regulatory requirements) that government (e.g., US) exerts on individuals/small businesses that try to compete with these much larger multi-national corporations. When government encourages (or at least doesn’t discourage) efficient infringement by larger multi-national corporations of the innovation developed by individuals/small businesses, individuals/small businesses can’t realistically compete as it now comes down to size, and in that regard, multi-national corporations will generally win. Additionally, productivity growth generally comes from individual/small business start-ups, not multi-national corporations which tend to consolidate (merge), often resulting in job loss, not job growth. Also, recall that the 2008 “great recession” in the U.S. was caused not by individuals/small businesses, but instead by the “melt-down” of large financial institutions deemed by the government to be “too big to fail.”

Anon

September 28, 2016 07:30 amBenny – all that you are advocating here is the lower innovation model of the established Big Corp entities.

The “derogation” is already present in your position, and it is you that have brought it to the table.

Seeing as you admit to the off-shore aspect, but miss the fact that patent systems (and the fruit of those system) are STILL driven for the benefit of the individual sovereign – and NOT for some “greater good of the world commune,” we see that your grasp of economics is on par with your grasp of patent law – and that is not a good thing.

Benny

September 28, 2016 05:49 amNo mention of continually increasing product and workplace regulation on productivity – if you think this is negligible, think again. Decline in one market often means an increase in another (geographically speaking – the US bust is China’s boom).

A weakening of the patent system will reduce investment in R&D, but increase the commodity market, as existing technology has less barriers to market entry – result – increase in overall production (though admittedly, mostly offshore). This also swells the retail and service sectors.

In economics, every dollar is somehow connected to every other dollar – I find the argument presented here rather simplistic (maybe even futile) in it’s attempt to pin productivity decline on a single factor without taking into account all other factors – including the fact that the expenses incurred in attorney fees in IPRs are included in the GDP calculations.

I fully expect Anon to tear this argument to ribbons in his usual derogatory style.

step back

September 28, 2016 02:05 amEG@7

And to add to that, some “friends” of the big C Court are more equal (more worthy of friendship) than others.

That aside, like the SCOTeti we all live in our own bubbles.

Strength of the patent system is but one of many symptoms/factors.

The world is far too complex to justify building a one dimensional correlation between patents and well being of citizens of the Earth.

EG

September 27, 2016 03:21 pmHey Anon,

As you bring “friends of the court” (aka, amicus), it’s even worse: there is a law review article in the Virginia Law Review that startlingly notes (and as also observed by the late Justice Scalia) that some SCOTUS justices rely upon unsubstantiated and untested statements/alleged facts in amicus briefs to support positions taken by those justices in opinions. Never mind that those statements/alleged facts aren’t even in the record supposedly before SCOTUS.

Anon

September 27, 2016 02:24 pmE.G.,

Emphasis on the word “conjecture” – and note that the Court is not held to act within its strictures of “current case or controversy” when it bases a decision on the mere possibility of something that only MAY happen in the future.

I would have them (seriously) consider that to start with.

Maybe they just need different “friends of the court”…

EG

September 27, 2016 01:06 pmHey Neal,

Thanks for the article, as well as the data. Your article/data shows that strong patent system equals increased innovation equals increased productivity. If only Congress would carefully consider what your article/data shows, versus the PR campaign by Goliath multi-nationals that gave us the AIA (Abominable Inane Act) have greatly weakened patent rights, causing decreased investment in innovation, leading to decreased productivity. SCOTUS also needs to carefully consider your article/data which refutes it factually unsupported conjecture that patents impede research/innovation.

Paul Morinville

September 27, 2016 12:16 pmFrom the bottom, the guy trying to get investment for a technology company, the lack of interest in patents astounds me. Investors just shrug their shoulders and say so what? That is a real problem. If inventors cannot attract capital to startup new high risk technology companies, do you think Google will? They can just sit back and reap profits like the big three automakers did for decades until the Japanese invaded us with much higher quality cars in the 70’s.

Night Writer

September 27, 2016 11:13 amAlso, what I find interesting is that Google et al. has been making arguments before Congress to lower taxes for spending on research and development and have been saying that they can handle this “innovation” thing with in-house investments. Thanks Mark Lemley and Obama.

Night Writer

September 27, 2016 11:11 amIt’s a good argument. I think too that Jimmy Carter saw this and that is why he set up the Federal Circuit. Reagan signed the bill, but it was Carter that put into action strengthening the patent system to end the malaise of the 1970’s.

I will bet some research would turn up a lot of debate about this at the end of Carter’s presidency.