In an earlier article on patent claim drafting I discussed what you must do before you ever think about writing patent claims. See A prelude to patent claim drafting. Today we pick up from there to discuss in a very basic way what must go into your patent claim.*

In an earlier article on patent claim drafting I discussed what you must do before you ever think about writing patent claims. See A prelude to patent claim drafting. Today we pick up from there to discuss in a very basic way what must go into your patent claim.*

Of course, this puts the cart a little bit before the horse. Let’s recall that in order to obtain a utility patent on an invention in the U.S. a non-provisional utility patent application must be filed. A utility patent is different from a design patent. A utility patent will define the structure of an invention, as well as the way it operates. A design patent merely protects the way a product looks, or in patent speak the ornamental appearance. While design protection can be quite important for certain inventions, and many inventors pursue both design and utility protection, utility patent protection is much stronger and typically the type of protection most inventors will elect to pursue.

The rights ultimately granted in a utility patent are defined by the patent claim (or claims) reviewed by the patent examiner and ultimately issued in the patent. While the specification (i.e., text and drawings) patent application must define the invention in its full glory, if you do not have claims covering a particular aspect of what you have disclosed then you have not been awarded those rights. Thus, the claims are frequently described as the most important part of the patent application because they are said to define the scope of the exclusive rights granted by the government.

Patent claims are difficult to read and even harder to write. The complexity of patent practice is why many (if not most) inventors will seek professional assistance from a patent practitioner, and the patent claims are the part of the application that are the most technically complicated.

What the Law Says About Patent Claims

A nonprovisional patent application must have at least one patent claim particularly pointing out and distinctly defining the invention, although most patent applications and issued patents will have many more than one claim. For the basic filing fee you can have up to three independent claims and up to twenty total claims without incurring any additional claim fees. Because a patent with more claims is considered stronger and more valuable as a broad general rule, you might as well have at least as many as you can for the price of the basic filing fee.

A claim may be written in either independent or dependent form. An independent claim stands alone and does not refer to or incorporate any other claim. A dependent claim refers to a previous claim and further limits the invention, either by incorporating an additional element or limitation not previously introduced or further narrowing an element or limitation that was previously introduced. A claim in dependent form incorporates by reference all the limitations of the claim to which it refers.

Three Simple Rules for Patent Claim Drafting

First, every patent claim needs a preamble, which is the introductory phrase in a claim.** The general rule is that the preamble of a claim does not limit the scope of the claim, but try and stay away from functional language if you can. Functional language is not wrong and it will ordinarily not limit a claim, but why take a chance? It is best practice to avoid functional language with only a few exceptions. For example, the patent examiner may be willing to give you a claim if you add some functional language. If that is the case then you need to decide whether it makes sense to add the language, which in many cases (although not all cases) it will. So try something like: “A shovel…” as a preamble instead of: “A shovel for digging…”

Second, every patent claim needs a transition.** The most common transitions are: “comprising” and “consisting of.” “Comprising” is by far the most common because it means the invention includes but is not limited to the elements identified in the claim. “Consisting of” is closed and means that the invention is only what is described. Generally speaking, you see “consisting of” as a transition in the chemical, biotech and pharmaceutical arts, or more broadly in areas where the technology is highly unpredictable.*** For mechanical and electrical inventions, software and methods, you will almost universally see “comprising” used because it will result in the broadest protection.

Third, the first time you introduce a limitation (i.e., an element, characteristic, internal reference, etc.) in a patent claim you MUST introduce it with either “a” or “an”, as is grammatically appropriate. (i.e., Primary antecedent basis). Subsequently you refer to the already introduced limitation by either “said” or “the.” (i.e., Secondary antecedent basis). This can be quite difficult for beginners because the three most common words in the English language — a, an and the — are all terms of art for patent claim drafting.

Patent Claim Drafting Examples

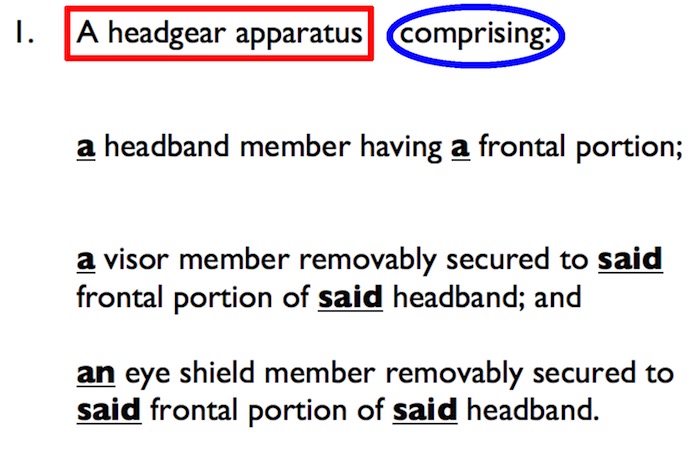

Below in an example of an independent claim that applies the above stated three simple rules, which is taken from U.S. Patent No. 6,009,555, titled Multiple component headgear system. I have put the preamble in a red box, the transition in a blue circle, and I’ve bolded and underlined the primary and secondary antecedent basis. I’ve used “said” in this example. The word “the” could have been used, but for those starting out “said” is probably best because it is a little more forced, which will hopefully help you make sure you applying this rule properly.

Illustrative independent claim 1, which is inspired by U.S. Patent No. 6,009,555.

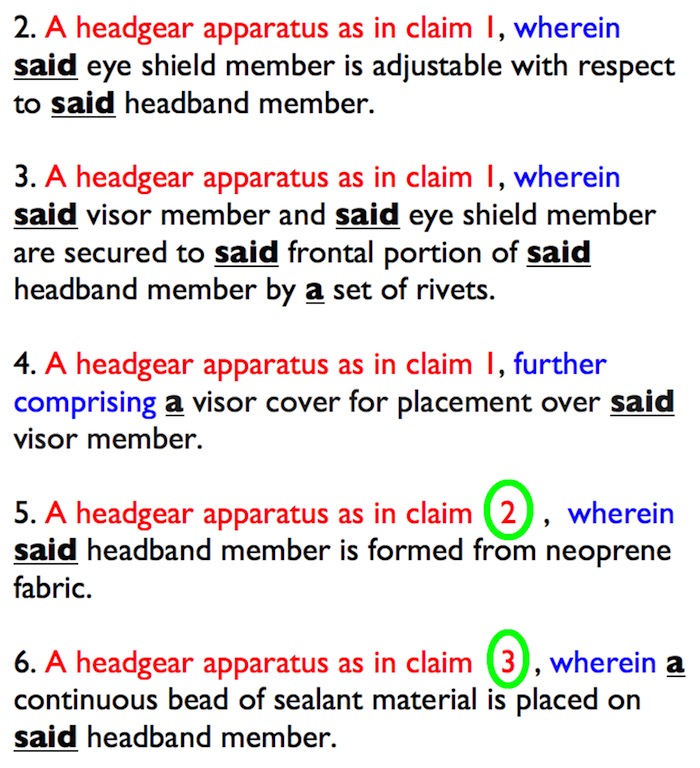

Below are examples of dependent claims, again using the invention found in the ‘555 patent as our guide. Once again, the preambles are in red, the transitions are in blue, the antecedent basis are bold and underlined. There are a couple things to notice, however. First, for dependent claims the preamble must match up with the preamble from the broadest independent claim in the chain. Here the invention is a headgear apparatus, so all of the dependent claims will be to a headgear apparatus. Second, the transition for a dependent claim will either be “wherein”, which is used when something already introduced is being further narrowed, or “further comprising” when something new is being introduced for the first time. Third, notice that claims 5 and 6 do not depend from claim 1, but rather dependent from other dependent claims. This is how you chain claims together. Finally, If you look at the patent you will notice this is not the order of the claims. There is a technical mistake in the order of the claims as issued in the patent, which could be raised by an examiner but typically is not any more. You are supposed to have all claims that depend on claim 1 before you have any claims that depend from claim 2 and so on. If you look at the ‘555 patent you will see that our dependent claim 4 corresponds with issued claim 8, which would lead to a Rule 1.75(g) objection if you do that in your application.

Illustrative dependent claims inspired by U.S. Patent No. 6,009,555.

Additional Information

For more tutorial information please see Invention to Patent 101: Everything You Need to Know. For more information specifically on patent application drafting please see:

- Can You Refile a Provisional Patent Application?

- Ten Common Patent Claim Drafting Mistakes to Avoid

- It’s All in the Hardware: Overcoming 101 Rejections in Computer Networking Technology Classes

- Two Key Steps to Overcome Rejections Received on PCT Drawings

- Drafting Lessons from a 101 Loss in the Eastern District of Texas

- From Agent to Examiner and Back Again: Practical Lessons Learned from Inside the USPTO

- Understand Your Utility Patent Application Drawings

- Getting a Patent: The Devastating Consequences of Not Naming All Inventors

- Getting A Patent: Who Should be Named as An Inventor?

- Make Your Disclosures Meaningful: A Plea for Clarity in Patent Drafting

- Avoid the Patent Pit of Despair: Drafting Claims Away from TC 3600

- A Tale of Two Electric Vehicle Charging Stations: Drafting Lessons for the New Eligibility Reality

- Background Pitfalls When Drafting a Patent Application

- Eight Tips to Get Your Patent Approved at the EPO

- What to Know About Drafting Patent Claims

- Beyond the Slice and Dice: Turning Your Idea into an Invention

- Examining the Unforeseen Effects of the USPTO’s New Section 112 Guidelines

- Anatomy of a Valuable Patent: Building on the Structural Uniqueness of an Invention

- Software Patent Drafting Lessons from the Key Lighthouse Cases

- Patent Drafting Basics: Instruction Manual Detail is What You Seek

- How to Write a Patent Application

- Admissions as Prior Art in a Patent: What they are and why you need to avoid them

- Patent Drafting: The most valuable patent focuses on structural uniqueness of an invention

- Patent Drafting: Proving You’re in Possession of the Invention

- Patent Drafting: Understanding the Enablement Requirement

- Patent Drafting 101: Say What You Mean in a Patent Application

- Patent Drafting 101: Going a Mile Wide and Deep with Variations in a Patent Application

- Learning from common patent application mistakes by inventors

- Defining Computer Related Inventions in a post-Alice World

- Patent Application Drafting: Using the Specification for more than the ordinary plain meaning

- Patent Strategy: Advanced Patent Claim Drafting for Inventors

- Patent Drafting 101: The Basics of Describing Your Invention in a Patent Application

- Patent Drafting for Beginners: The anatomy of a patent claim

- Patent Drafting for Beginners: A prelude to patent claim drafting

- The Inventors’ Dilemma: Drafting your own patent application when you lack funds

- Patent Drafting: Describing What is Unique Without Puffing

- 5 things inventors and startups need to know about patents

- Drafting Patent Applications: Writing Method Claims

- An Introduction to Patent Claims

- Patent Drafting: Define terms when drafting patent applications, be your own lexicographer

- Patent Language Difficulties: Open Mouth, Insert Foot

- Patent Drafting: The Use of Relative Terminology Can Be Dangerous

- Patent Drafting: Distinctly identifying the invention in exact terms

- Patent Drafting: Understanding the Specification of the Invention

- Tricks & Tips to Describe an Invention in a Patent Application

- Invention to Patent 101 – Everything You Need to Know to Get Started

- Patent Drafting 101: Beware Background Pitfalls When Drafting a Patent Application

- Describing an Invention in a Patent Application

- The Key to Drafting an Excellent Patent – Alternatives

- The Cost of Obtaining a Patent in the US

UPDATED on Tuesday, December 13, 2016, at 2:42 pm ET to add the comment found below at **.

_______________

* This and other articles on IPWatchdog.com should not be viewed as encouragement for those who can afford professional assistance to cut corners and do things themselves. If you can afford to hire a patent practitioner you should. Of course, the more you read and understand the better prepared you will be to meaningfully assist your chosen patent attorney or agent. For many, however, the choice will be either to do it yourself or give up. The reality facing all entrepreneurs is that there is never enough time or money to do everything; that is the nature of being a start-up entrepreneur or serial inventor. This tutorial, and the many other articles on IPWatchdog.com are required reading for those who have consciously decided to pursue a patent process on their own. Proceeding on your own comes with great risk. Read as much as you can, educate yourself to the greatest extent possible, and try and find professionals who will assist you piece by piece as necessary.

** A preamble and transition should be thought of as absolutely required unless you are claiming a new compound or synthetically created element. For example see U.S. Patent No. 2,699,054 (particularly claim 2), which covers tetracycline. Also see U.S. Patent No. 3,161,462, which covers Element 96. It is the extraordinary situation where claims will not have a preamble and/or a transition. See alsoMPEP 2173 (t).

*** A full explanation as to why this is true goes beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say for now that when you use “consisting of” as a transition you narrow the universe of possible prior art. Additionally, in unpredictable fields this can be useful because you want to claim what you know works and not capture too many things in your claim that will not work, which could render the claim invalid.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Ad-1-The-Invent-Patent-System™-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Patent-Portfolio-Management-2024-sidebar-super-early-bird-with-button-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

21 comments so far.

Gene Quinn

January 14, 2017 01:26 pmVince-

I have some information on writing method claims here:

https://ipwatchdog.com/2016/06/18/patent-applications-method-claims/id=70212/

I will try and circle back with more on method claims over the next couple weeks.

-Gene

Vince S

January 14, 2017 01:41 amHi Gene,

I truly appreciate what you are doing here. Could you kindly give any indication when you might get to “writing method claims and advanced claim drafting strategies. Stay tuned!”

I am drafting a provisional patent for something that, relative to the examples given, is so big I struggle to know how to deal with the translation to minutia, or if I should even try. This is akin to inventing a car if all we had is motorbikes. Sure some people did put extra wheels on their wheelbarrows and motorise them, and others did build passenger jets without wings and put wheels on them, which is the kind of prior art around, but nobody looked at it from the perspective of mass transport of a population. Not quite, but sufficiently illustratively for the purpose, I am trying to patent a car in the modern era where lots of the bits exist but just never assembled as a 5 person personal transport device. Do I just patent an aerodynamic box with doors, 4 wheels and a method to propel and steer them? which could be anything from lightweight kevlar boxes that are self propelled to the biggest stonker of a boat engine or anything in-between.

I am not meaning to ask for advice as I don’t think that is what you want to do here, just point out that people with big ideas have a heck of a lot to wade through, and even how to approach the whole patent task when that is where you are coming from is pretty opaque. It needs to be knocked down to bite sized chunks, but if I was patenting a car I could easily write a few hundred claims as I would have ideas about how each of the sub-systems should be done, and able to claim them widely enough that I could intend for example to use mechanical, hydraulic and electric power assisted steering – which took the real inventors some decades to get through that set of developments. I already know a lot about the pathway of where I will be taking this thing, despite that much of it is just conceptual ideas in my head. Could write many pages describing this, but as you point out, the practical execution of the protection all comes down to the claims so I am starting there. Love some tips!

By way of background, for 18 years I have had this idea for a methodology to knock 20% off the road toll at population scale level and, now that some of the last bits of supporting technology is available, I am finally building an (expensive!) proof of concept prototype. All funds are going into that and it would be a poor value case to put money into a patent .vs. getting the details sorted, and I even wonder if I should patent it at all as what I am doing is simple enough to copy big picture but the devil is in the details, and I have a lifetime of experience getting details right in big complex projects. It may just be the big picture concept I should patent and leave the details out entirely…

All very confusing? What I will actually be doing is submitting a provisional patent application in the coming week then I have a year to get the funding together for the first major roll-out, which WILL include having a patent lawyer assist with the filing of the formal patent. I am also going to try asking for a pro-bono patent review of the provisional before submitting it, which if it can happen might get better protection. Eventually the story will turn up on http://www.vrdriversim.com, there is a teaser there now.

All this adds up to I am pretty keen to read your further thoughts on advanced claim strategies – any chance you will be getting that one out any time soon? Thanks again for all that you have done in this space.

Anon

December 13, 2016 07:12 pmGene,

I suppose one lesson from the exchange to the audience that you were aiming at is that patent law can be complex, and exceptions abound.

Like other areas of complex law, there are definitely traps for the unwary.

Gene Quinn

December 13, 2016 02:56 pmI’ve amended the article to take into account the comments. Obviously, it is possible to have a claim without a preamble and a transition if you claim a compound and/or a synthetically created element. If anyone has any other examples I’ll amend the article further.

As for whether I’m comfortable with saying a claim needs a preamble and a transition, I am. That is how claims are written. To suggest otherwise is to look for the extreme exception and then attempt to make that extreme exception into the rule by suggesting that a claim body would be definite enough without any context.

Earlier in the thread In In re Fisher is used as an example, but that example includes a preamble and a transition. “polypeptide of at least 24 amino acids” would be the preamble and “having” would be the transition. See MPEP 2111.03.

Joachim Martillo

December 13, 2016 06:30 amI meant “the list of nominative absolutes” and not “the last of nominative absolutes”.

Joachim Martillo

December 13, 2016 06:25 amI am taking the patent bar exam on Dec. 27 and am studying for the exam by means of the PLI patent bar preparation course.

One of the post course sessions goes over patent 5,402,728 which has the following claim.

I really hate nominative absolutes, and the phrases below are examples:

1) “said actuating means being a composition that undergoes a phase change from a solid to a liquid” and

2) “said larger volume causing a pressure build-up within said cavity”.

Nominative absolutes provide attendant circumstance to the verb, which in this case is “claim” from the phrase “I claim”, which precedes the list of claims.

Because the nominative absolute construction can be construed to have temporal, causal, conditional, or concessive force, the construction is inherently ambiguous even if not indefinite in BRI sense. Nominative absolutes can be painful to translate into other languages.

A “wherein clause” provides further delineation of a limitation, and from the grammatical standpoint “wherein” is equivalent to the prepositional phrase “in which” and the antecedent of “wherein” should be the noun phrase to which the claim is directed. In this case the noun phrase is “a releasable attaching apparatus”.

When I write claims, I prefer to put a list of “wherein” relative adverbial clauses after the recitation of the limitations (thus at the same grammatical “nesting level” as the transition that also modifies the noun phrase to which the claim is directed). I then place the last of nominative absolutes after the relative adverbial clause list. Because the nominative absolutes modify the verb that precedes the claim list, the nominative absolutes are at the next lower grammatical “nesting level” in relation to the list of relative adverbial clauses.

The claim writer was not as precise with respect to grammar as I am. I would have written the claim as follows.

I eliminated the nominative absolute and the “wherein” clauses because they seem more appropriate to dependent claims. In the above formulation, the relative pronouns of the relative clauses show the correct intended relationship of modifier and modificand — something that should be immensely useful in any infringement trial.

I do not deny that nominative absolutes can be useful in claims. I only prefer to avoid promiscuous use of them and to employ them only in circumstances where possible ambiguity is minimized. Nominative absolutes might also be useful in introducing claim specific terminology and definitions, but I have never seen them so used.

In case readers have not guessed, I am building an automatic claim parser to assist in clarifying what a claim will mean to a grammar-aware judge in an infringement trial.

An automatic claim parser that produces a clear modifier-modificand chart may also help during a Markman hearing and in persuading a jury of the validity of an infringement complaint.

Prizzi’s Glory

December 12, 2016 10:23 pmHere is the rule for a chemical formula in a claim.

AAA JJ

December 12, 2016 09:08 pmYou’re comfortable with how you characterized the rule? What rule is that?

AAA JJ

December 12, 2016 09:06 pmWhat rejection or objection to the claim could the examiner make for lacking a preamble or transition phrase? What section of 35 USC requires a claim to have either?

Prizzi’s Glory

December 12, 2016 05:28 pmWe find a similar situation in the tetracycline patent.

Prizzi’s Glory

December 12, 2016 05:26 pmHere are 1 word claims from US3775489.

The individual words are all domain specific terminology that subsumes the patentese preamble and transition. A pure patentese form of the claim would be far less clear to a PHOSITA than the one word domain specific language.

Edward Heller

December 12, 2016 04:25 pmAAA JJ is right.

One of my colleagues got a patent on an article of manufacture having two words, one of them “A.”

I long ago stopped using any preambles other than the broad classification: apparatus, process, system, composition,or manufacture. Too often in litigation the preamble comes back to haunt.

Prizzi’s Glory

December 12, 2016 04:46 amI would explain the issue differently.

Element 96 is well understood physicist terminology that implicitly expresses patentese idiom as follows.

“An atomic structure comprising: a nucleus that has exactly exactly 96 protons.”

An expert would affirm that “Element 96” is tremendously clearer to a PHOSITA than the patentese form of the claim.

Gene should have stood his ground. All patents have preamble and transition, but in certain technological arts the preamble and transition can be subsumed into well understood domain specific nomenclature, abbreviations, or (even) diagrams.

Patent practitioners must have at least some non-legal technical knowledge.

Gene Quinn

December 11, 2016 03:27 pmI suppose I should have written it saying that unless you are a Nobel Prize winning level independent inventor working in your garage you must have a preamble in your claim and you must have a transition.

I probably should have just deleted these comments rather than run the risk that any newbie would want to listen to the “well you really don’t need a preamble or a transition” line. Because if you’ve ever worked with independent inventors or those who are new to the field you’d know that if you said that then what they would hear is simply “a preamble and a transition is unnecessary.”

Interestingly, this article comes from a slide deck prepared years ago in cooperation with the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

For me, when teaching newbies, if you need to do something in 99.9999999999999999 percent of cases I’m comfortable saying that asymptotically approaches 100% and I’m comfortable with how I characterized the rule. I’m sure I could look up the applications you file I wouldn’t find any examples of claims without preambles or transitions, but I get it. What I said is only right in 99.9999999999999999 percent of cases and clearly that is not always.

So please, go ahead and file claims without a preamble and without a transition. I’m sure that is a wonderful strategy! I just ask you report back and let us know of your great and glorious success with that strategy.

step back

December 11, 2016 03:03 pmWell let that be a lesson to your newbie patent law students here of how persnickety the law can be.

There is a difference between absolutist words like “need” “must” “shall” and less rigorous words like “should”.

Every patent claim “should” be written with a preamble and a transition phrase because those two items can respectively provide important benefits such as …

And I’ll the teacher fill in the rest. 🙂

Gene Quinn

December 11, 2016 01:17 pmI love it. I write a basic claim drafting tutorial that by the express statements in the article are intended for those who are newbies and know nothing about patent claim drafting and the learned patent attorneys among us are taking issue with the statement that “every patent claim needs a preamble” because out of the millions of patents that have been issued there is one example of a patent that was issued on a synthetic element having an atomic number 96, and rather than following proper protocol, which is to have a preamble, which could have (or probably even should have) read “A synthetical element”, the patent examiner allowed a claim to read: “Element 96.”

As I explain whenever I teach patent bar students, the rules are the rules and what you will be tested on. The fact that some examiner will ignore the rules and let you get away with something that is not allowed doesn’t mean that the rule is not the rule.

So please, be my guest and write your claims without preambles and transitions. But for those who don’t want to have their claims rejected and objected to you will include a preamble and a transition in every claim.

Hoping that an examiner will allow a claim without a preamble and transition is stupid. Expecting a claim that has issued without a preamble and a transition to remain valid upon challenge is even more stupid.

Benny

December 11, 2016 05:31 amGene at 2,

True, but there are exceptions. See claim 1-8 of US3161462 for a rather extreme example.

step back

December 10, 2016 05:45 pmYes I know, 112 indefiniteness.

(Not as to the value of Pi but as to meaning of mixture ratio 😉 )

step back

December 10, 2016 05:42 pmIt would be stoop8 not to have a transition (comprising or consisting essentially of) but it would not be impossible.

Example: What is claimed is: Compound A mixed with compound B in accordance with a mixture ratio A/B equal exactly to Pi. 😉

Gene Quinn

December 10, 2016 02:27 pmAAA JJ-

You are wrong.

-Gene

AAA JJ

December 10, 2016 10:55 am“First, every patent claim needs a preamble…”

No it doesn’t.

“Second, every patent claim needs a transition.”

No it doesn’t.