Patenting can be a long and costly process, and the uncertainty of the outcome can greatly impede the patentee’s ability to budget and plan effectively. In an ideal world, a practitioner (and by extension, their client) would have a roadmap to chart the probable actions of the examiner at the patent office responsible for each of their applications in prosecution. Knowing that the future course of prosecution is more likely to be negative and/or lengthy could make all the difference for applications assigned to more challenging examiners.

Patenting can be a long and costly process, and the uncertainty of the outcome can greatly impede the patentee’s ability to budget and plan effectively. In an ideal world, a practitioner (and by extension, their client) would have a roadmap to chart the probable actions of the examiner at the patent office responsible for each of their applications in prosecution. Knowing that the future course of prosecution is more likely to be negative and/or lengthy could make all the difference for applications assigned to more challenging examiners.

The good news is much more hard data on patent examination are available today than ever before, and the data contain a wealth of useful detail. TurboPatent has analyzed approximately 100 gigabytes of data compiled on public PAIR. From all cases filed in the last 10 years, we filtered for all final dispositions in all of 2015 and 2016. Taking this data, we examine TC-2800 at three levels of detail: the overall statistics; a breakdown of the allowance rate by stage of prosecution; and finally, all the way down to the extremes of variation exhibited by individual examiners. The deepest investigation exposes a range of patterns unobserved in a focus on allowance rates alone. Relatively small changes in allowance rates, for example +/-15%, correlate to a 2x change in the effort and cost of an allowance.

TC-2800 is the largest of the eight technology centers responsible for utility patent applications, disposing 21% of all utility applications and 40% more than the runner-up tech center, TC-3700. TC-2800 examines applications in a broad range of physical science related subject matter: semiconductors, electronic memories, electrical circuits, optics, printing, measurement and test equipment, and related topics.

The average prosecution road map of TC-2800

TC-2800 exhibits extreme characteristics relative to its peers by several measures. TC-2800 features the:

– shortest pendency at 29 months;

– lowest percentage of granted cases involving an RCE at 22%;

– lowest percentage of allowances with interviews at 20%;

– Lowest percentage of allowances by appeals at a mere 2%.

For the all-important allowance rate, TC-2800 stands alone at 82%, 9% above the overall rate for utility applications of 73%.

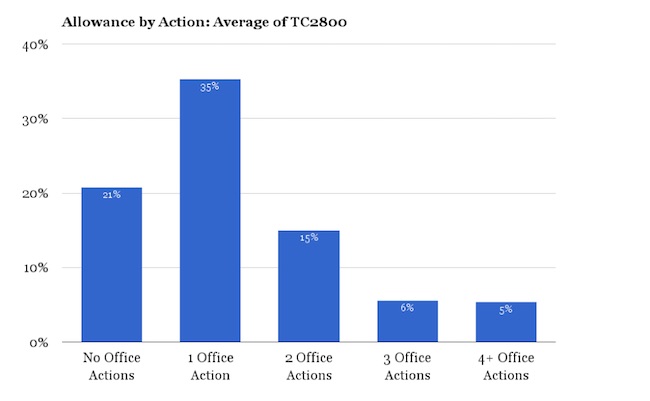

Breaking down the allowances by stages of prosecution reveals the pattern depicted in Figure 1. Examiners in TC-2800 allow over a 5th of cases without an office action, higher by a factor of 2 than 6 of the 7 other tech centers. The exception is TC-2600 at 13%. The largest share of allowances come after one office action. The tail of two, three, and four or more office actions collectively have an allowance rate of 26%.

The summary statistics for TC-2800 obscure the particulars of the 1867 unique combinations of examiner and art unit. (If the same name is associated with different art units, we count those as distinct, though they may or may not be the same person). The deeper story in the data lies in just how far individual examiners can vary from the average pattern, how many examiners vary, and how those variances are obscured by the simple allowance rate, only to be revealed in the richer details of the underlying patterns.

The 10 examiners in TC-2800 with the most compressed prosecution

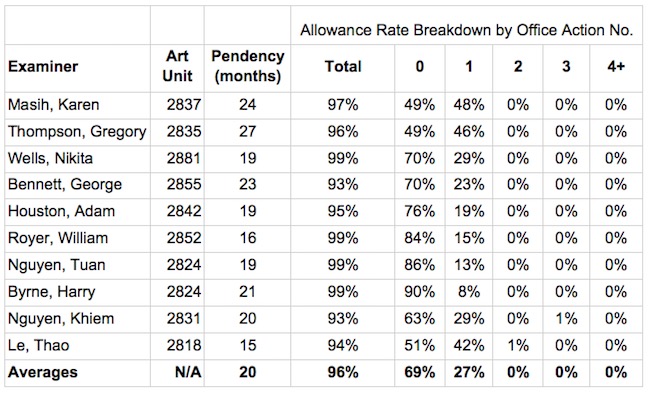

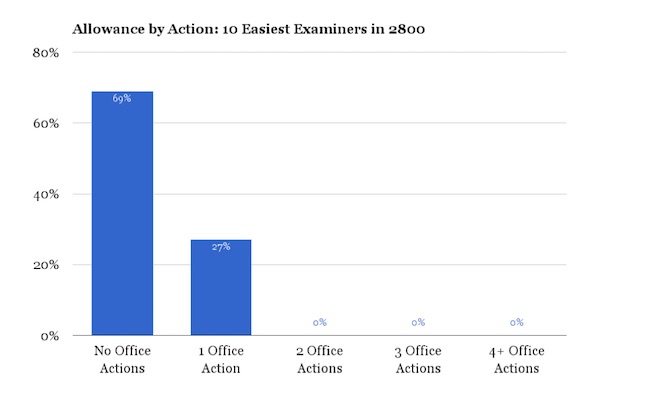

For analysis of examiners at the extreme ranges of prosecution patterns, we restrict the data to the 1083 examiners disposing at least 50 cases in the 24 month period of the study, a group which still accounts for 87% of the dispositions. We identify a set of “easy” examiners, those with a compressed pattern of prosecution, by sorting along the probability of receiving an allowance after exactly two office actions. Table 1 summarizes the data for the ten easiest examiners by this measure.

Table 1. The 10 examiners in TC-2800 with the fewest allowances after exactly two office actions.

The 10 examiners hail from 9 different art units. Collectively, they disposed 1100 cases at an average allowance rate of 96% and pendency of 20 months. Not only do these examiners have an extraordinarily high allowance rate on average, their allowance rate on the first examination, without even a first non-final rejection, is 69%, almost equal to the overall allowance rate for utility applications across the entire patent office.

Whether this foreshortened pattern of prosecution is “good” for the applicant is a subject for further research. Were the root cause to be insufficient diligence, that would by no means be a favor to an applicant. A second possible explanation is selection bias in assigning easily allowable cases to a small set of examiners, also a topic for further research. A third possibility is that enough easy cases were assigned to these examiners by random chance to create this pattern. This last hypothesis we explored by randomizing the names on each case (keeping the art unit the same). Instead of 10 examiners with at most 1% of their allowances after the first office action, we found not a single examiner below 10% on that score.

Another way to characterize the variation in prosecution on the short end is to take the total probability of allowance after the second action (26% in the average) and ask, how many examiners fall at or below half that? The answer is 207 examiners, which accounts for 20% of dispositions with an average pendency of 22 months, allowance rate of 94%, and 0.7 office actions.

The 10 examiners in 2800 with the most lengthy prosecution

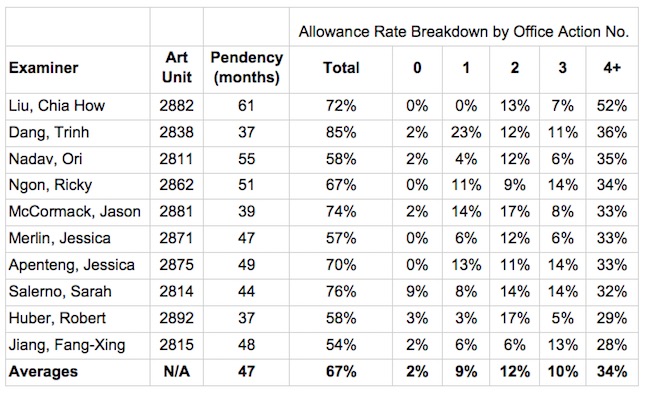

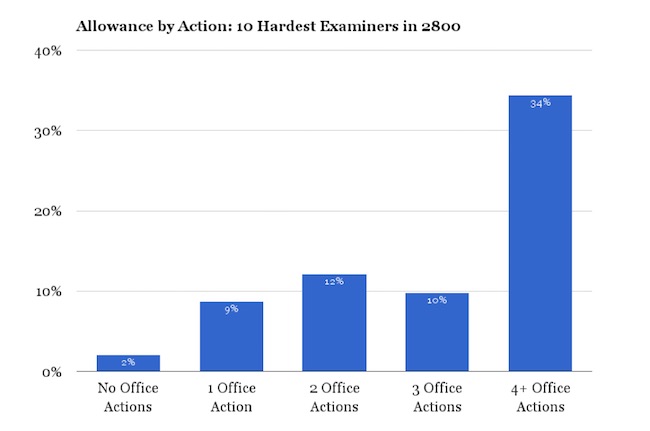

Turning to the other end of the spectrum of prosecution difficulty, we identify a set of “hard” examiners, those with a pattern of prolonged prosecution, by sorting along the probability of receiving an allowance only after four or more office actions and extracting the highest ranking 10. Table 2 summarizes the data for all 10 “hard” examiners.

Table 2. The 10 examiners in TC-2800 with the most allowances after four or more office actions.

In this instance, the 10 examiners are spread across 10 art units. They disposed 726 cases at an average allowance rate of 67% and average pendency of 47 months. The average allowance rate is far from being alarmingly low. It is only 6 points below the USPTO average and equal to or above the allowance rates of four other entire tech centers (1600, 1700, 3600, and 3700).

If one were only focused on the allowance rate, one might be inclined to dismiss the low end of TC 2800’s allowance rate as being of little consequence. However, the additional 18 months of pendency over and above the TC-2800 average begins to hint at the practical effect, and cost, of extra rounds of prosecution and RCEs. This group of examiners trickle out their allowances only over the course of many office actions, such that the majority of granted patents won come only on or after the fourth round. Assuming a ballpark cost of an office action at $4,000, being assigned to one of these examiners could increase the cost of prosecution by $10,ooo over an average case in TC2800. Given that a client’s budget for new IP production and maintenance is likely to be a zero-sum game, such variations in examiners’ patterns can have practical consequences.

As on the short end, the long end of prosecution patterns in TC-2800 is a fair share of all dispositions. Given that on average in TC-2800, 5% of allowances occur after the fourth office action, how many examiners fall at twice that percentage or above? The answer is 224 examiners, which accounts for 15% of dispositions with an average pendency of 37 months, allowance rate of 73%, and 2.3 office actions.

Taking the long and short together, in TC-2800 one has a greater than 1/3rd chance of being assigned an examiner either half as hard or twice as hard as the average. What examiners are you corresponding with currently in your prosecution of utility applications? Do you know their typical patterns of prosecution? Thanks to the transparency of the USPTO and its efforts to publish large data archives in machine readable form, answers to such questions are now firmly in the realm of technical and commercial feasibility for every active examiner, and consequently open to study by every practitioner and client.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

15 comments so far.

TC1700 Examiner

March 17, 2017 04:20 pmGreat commentary! I can back-up TC2400 on the SPE claim. Some SPEs are just terrible and they never get “caught” as it is the Examiners who suffer under their tutelage.

Also, I have a 4th/5th type of SPE. I temporarily had a SPE that would often place terrible barriers on me in order to prevent allowances. Some of her favorite tactics included requiring flip searches of multiple large subclasses (looking at all of the patents/pubs in a subclass) in more than one area, not letting me know she had a problem with a claim until after I had worked with an atty to compromise on an allowable claim, and finding barely applicable art and requiring me to make a rejection over it. All of these were designed to wear me down until I just gave up and issued a rejection over the case.

As for the results of her guidance, my allowance rate went WAY down. In fact, under her I only allowed 1 patent (over a 10 month period and it was a PPH case). For comparison, I allow ~30 patents on average in a 10 month period (which about normal for my art unit). I hated going to work as I felt pushed around and undermined. I also felt terrible for the Applicants that that either had their allowances delayed and had to face increased examination fees due to her.

TC2400 Examiner

February 10, 2017 12:10 pmAfter some digging around, I found all the most compressed examiners are primaries. For all the most lengthy examiners, only 3 primaries, 2 currently on the Full Sig Program and 5 are without Full Sig Authority. I believe these numbers confirms part of my suspicions.

For the most lengthy examiners, 4 are from optics and 4 are from semiconductor arts. 1 from Ciruits and 1 from Printer/measuring&testing. For the most compressed examiners, 4 are from circuits, 3 from semiconductor, 2 from printer/measuring&testing, 1 from optics.

Mark Nowotarski:

I by no means imply all attorneys want to milk more hours. Billable hours is just 1 of many factors that impact pendency. On the other hand, having worked in a patent boutique, I know the pressure to bill more hour for junior associates.

Gene:

I agree that none of the quality initiatives address improving the quality of SPEs. Maybe we should also start from the top and improve the quality of TC directors. I know that will never happen.

There are several things Andy Faile can do to improve qualities of the SPEs:

For SPEs that do not know the art, make them learn the art. Ask them to put that item in their FY17 quality action plan. How can a SPE rate and improve the quality of his/her examiners, if the SPE does not even know the art/technology?

2nd, I know some examiners complain that their SPEs never have time for them. Management needs to do something about

1. those SPEs that are coasting to retirement,

2. hoteling SPEs that are never available to their examiners.

3. SPEs that are on so many projects/details (Director Wannabes) that they do not have time for their examiners.

Erin-Michael Gill

February 9, 2017 01:00 pmNikita Wells was my old Primary Examiner back when I was in 2881. He’s a Russian Physicist by training and one of the smartest guys I met at the PTO. There is a category of invention where inventors seem to break the known or established laws of physics. Those time machine/ free energy / anti-gravity devices get sent to examiners with the experience to review and prosecute those types of cases. He was one of the few examiners trusted with those (often very complex) cases. I can confirm having worked with him that the number of inventions of this type was significant and they had an allowance rate from him of exactly 0%. However, he also had his normal docket to work through as well as supervising a number of us junior examiners. He always drove compact prosecution – teaching us to call the attorneys with what we found in examination, and see if we could agree on an examiner amendment to dispose of the case. In doing that, all the allowances made by us junior examiners would show up in this data set as having him as the primary (which is correct). However, abandonments which were made by our applicants would not show up on his docket. So it’s as if one primary examiner with 5 junior examiners driving compact prosecution is getting 5 times the allowances without also showing the associated abandonments.

(Proof: patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/pdfs/US6809325.pdf)

While I certainly respect the effort to mine this data – the data science aspect is critical to driving actionable conclusions.

Note: I’m comfortable sharing this info as Nikita has recently retired.

Mark Nowotarski

February 9, 2017 12:40 pm“Attorney would not amend to allow based on my suggestions because attorney wants to bill more hours.”

TC2400 Examiner: There is a common misconception that agents/attorneys deliberately prolong prosecution “just to bill more hours”. Quite the opposite is true. Speaking for myself, I am quite reluctant to prolong prosecution because it mean I have to bill more hours. That leads to client dissatisfaction since their patents cost more and take longer to get. It’s much better for business if I can get to allowances as quickly and as efficiently as possible. Client’s then see patents as a good value and file more.

That being said, if an examiner’s suggestion does not give an applicant the coverage the applicant needs, then the attorney/agent has little choice to but to continue prosecution. It’s not personal. It’s just the attorney/agent doing what is in the applicant’s best interest.

Gene Quinn

February 9, 2017 09:41 amTC2400 Examiner-

I won’t speak for the author, but I write to comment on your final points about what examiners would say.

I hear that a lot, and there seems to be a lot of merit to what you say based on all the stories I hear. SPEs not letting examiners allow cases and not understanding the art is a real problem. Interestingly, none of the USPTO quality initiatives would do anything about these very real problems. Instead, the USPTO places all the blame on applicants and attorneys, which is not fair. Having said that, I have certainly seen prosecution where it was impossible to understand the strategy being employed and certainly looked like the attorney/agent was just forcing a final rejection without any attempt to amend and take what could be obtained. So there is certainly blame to go around everywhere. The USPTO loses credibility, however, when it refuses to listen to examiners who continue to point to #1 and #2 on your list. A wholistic approach to fixing the Office is required.

Gene Quinn

February 9, 2017 09:35 amSlapshot-

First, I don’t believe I ever said that examiners who refuse to allow were committing fraud. Sure, they should be fired or reassigned, but fraud is a very specific allegation.

Second, trying to figure out what Duh meant seems like a fools errand really. His comment did not communicate a clear thought. And 95% of examiners do not refuse to issue patents, so what you are saying he meant couldn’t have been what he was saying.

-Gene

Slapshot

February 9, 2017 09:12 amGene,

You’ve missed the point. Duh was talking about allowance rates (calling back to your articles about 3600 and minuscule allowance rates), not timecard fraud.

TC2400 Examiner

February 8, 2017 08:52 pmI have a few questions for the author. First I like to thank the author for this study. This is a new angle that I have not seen before. Before I raise my questions, I assume the allowance rate for office action No. 0 is referring to first office action allowances, as normally called in the PTO. The allowance rate for office action No. 1 is for allowances after 1 round of rejection.

How many of these most compressed examiners are primaries? How many of these most lengthy examiners are junior examiners? I suspects that these most lengthy examiners are most likely junior examiners and their numbers are a reflection of their SPEs.

What about the quality of the patent issued? My personal opinion is that if an applicant receives a patent from an Examiner with a 99% allowance rate, the patent is most likely not worth the paper it is printed on. 69% allowed cased from the so called “top 10” are done without any rejections. How many of these allowances had prior art rejections? When applicants pay for a search fee, are they getting their money worth? In other words, do the top 10 have better quality than the bottom 10?

TC 2800 has 4 art areas, and allowance rate would not be the same across the board depending on age of the technology. Why would you treat the 4 art areas the same? Would optics have the same technological complexity as circuits and thereby resulting in different allowance rates?

Did Director Lee’s quality initiatives have an impact on these numbers?

Finally, if you have a chance to interview some of these examiners on why their pendency is so high, I suspect their answers would be:

1. My SPE would not let me allow.

2. MY SPE does not know the art.

3. Attorney would not amend to allow based on my suggestions because attorney wants to bill more hours.

4. Attorney filed RCE because my rejection is solid.

-TC2400 Examiner

Gene Quinn

February 8, 2017 10:53 amDuh-

Care to explain why you think 95% of patent examiners are engaging in fraud?

I realize you are just being intellectually stupid and trying to excuse the 5% of patent examiners that were found to have submitted time for which they didn’t work, some of whom admitted their fraud here on IPWatchdog.com. But to be so intellectually stupid behind a fake name and a fake e-mail address. Wow! What a coward you are!

-Gene

Mark Nowotarski

February 8, 2017 10:39 amInteresting analysis. I took a bit of a deeper dive in one individual art unit (2811) where presumably applications are all directed to the same technical field and are uniformly distributed among the same group of examiners. I looked at cases where there was an office action in the past two years.

I would have to agree with Ed’s basic conclusion that there is a very large variation from examiner to examiner in terms of ability to efficiently reach agreement with applicants on whether or not to allow or abandon claims. There were 14 examiners in this art unit that handled 100 or more cases in the past two years. The number of actions between filing and issuance for different examiners ranged from 0.8 to 3.9. That’s more than a 4X variation. The difference in percent of applications where a notice of appeal was filed was even more dramatic. That ranged from 1% to 20%.

This enormous range in examiner performance for presumably relatively similar applications suggests that USPTO management would do well to explore where this variation is coming from. Is it Training? Systems? Standards? Experience? Qualifications? Understanding the variation may be the key to real quality improvements.

Eric Berend

February 8, 2017 05:49 amThank you very much for this breakdown. This is useful information that advances the debate regarding U.S. patent issues.

I would think there is utility for inventors and patent practitioners in publishing a series of articles such as this one, for each of broadly different types of inventions.

Duh

February 7, 2017 09:09 pmI would like to see Gene proclaim ‘Fraud!’ at these >95% examiners the way he did at the <5% examiners.

Curious

February 7, 2017 04:53 pmI would be very interested to see that same type of analysis used with the examiners in the business method art units within Tech Center 3600. I suspect that even the “10 examiners in 2800 with the most lengthy prosecution” are pushovers when it comes to most examiners in 3600.

Cheesy Bread

February 7, 2017 03:56 pm> Were the root cause to be insufficient diligence, that would by no means be a favor to an applicant. A second possible explanation is selection bias in assigning easily allowable cases to a small set of examiners, also a topic for further research. A third possibility is that enough easy cases were assigned to these examiners by random chance to create this pattern.

You didn’t account for a fourth possibility, which is that those examiners allowed the cases early because they are prone to calling the patent prosecutor to make an examiner’s amendment and issue an allowance.

Carol Owen

February 7, 2017 03:37 pmSounds very promising – thanks, Ed.