Patent valuation is a topic that features often on this blog. After all, IP represents an important part of a company’s assets. Unfortunately, intangible assets in general, and patents in particular, are simply not easy to value. In a recent series, IPWatchDog explored questions like: What is a good price for a patent? Are you getting a great bargain or are you being overcharged? Are you overcharging or selling yourself short? Whether as a buyer or a seller, those are hard questions to answer without comprehensive pricing analysis. Various strategies have been proposed for pricing patent portfolios. Known pricing strategies are either free but unreliable, or more reliable but quite expensive.

Patent valuation is a topic that features often on this blog. After all, IP represents an important part of a company’s assets. Unfortunately, intangible assets in general, and patents in particular, are simply not easy to value. In a recent series, IPWatchDog explored questions like: What is a good price for a patent? Are you getting a great bargain or are you being overcharged? Are you overcharging or selling yourself short? Whether as a buyer or a seller, those are hard questions to answer without comprehensive pricing analysis. Various strategies have been proposed for pricing patent portfolios. Known pricing strategies are either free but unreliable, or more reliable but quite expensive.

Pricing strategies within the free-but-unreliable category include:

- Pricing based exclusively on size of a portfolio (number of patents), times a fixed multiple

- Pricing based on number of applications filed per period, times a fixed multiple

- Cost-based valuation, which is based on the premise that each patent is worth what you paid for it (in R&D, patent office fees, and legal fees)

These pricing strategies are within reach of people outside the patent field, whereas the more detailed analyses described next require knowledge of the patent system.

The other kind of pricing is expensive to obtain. You basically have to hire an expert. But the resulting valuation is much more accurate. These pricing strategies include:

- Market-based valuation, which attempts to use a like-for-like analysis of patent prices. For single patents or small portfolios, it can be difficult to obtain a “benchmark” based on an earlier sale of a comparable product. But market-based valuation is effective for larger portfolios.

- Income-based valuation, which is the most reliable and most used valuation strategy. It works by first determining a royalty rate by mapping the patent onto a product and deciding what fraction of the product is covered by the patent (typically a fraction of a percent). The royalty rate is then multiplied by unit price and units sold to arrive at a valuation.

Without hiring an expert from the patent field, it is difficult to get meaningful information about the value of a particular patent at a glance. As a result, investors often merely look at the size of a company’s portfolio or its rate of filing new patent applications, at least as a preliminary indicator. This provides an inexact but fast way of estimating the value of the company’s patent portfolio. However, the use of size as a quality metric among investors has some unfortunate side effects.

Particularly for mid-to-large sized companies, the resulting competition to have the biggest patent portfolio can lead to “portfolio bloat”. In other words, “everything and the kitchen sink” that is happening at the company’s R&D is packaged into patent applications — not just real, groundbreaking inventions. Some companies even have yearly quotas for number of filings or number of patents granted that they aim to achieve. This results in “filler applications”, filed primarily to achieve a quota. Often, these “filler applications” do grant as patents, but with a scope of protection that is factually nil. In other words, the scope of protection is so small that the patent has no deterrent effect on competitors. Some patents are granted with claims that are so detailed and specific that you couldn’t infringe them without willfully aiming to. However, to unsavvy investors, “a patent is a patent”. And so companies that follow this kind of strategy do sometimes get rewarded with a higher valuation than they perhaps deserve.

Although prosecuting the applications that issue as these “filler patents” provides an easy source of income for the USPTO and law firms, it is unsatisfying work. Furthermore, “portfolio bloat” represents an inefficiency in the economy, as thousands of meaningless “filler patents” grant each year. This contributes to information overload and makes the patent world even more opaque to outsiders than it already is. Also, the practice of “portfolio bloat” ultimately undermines trust in the patent system, as “filler patents” dilute the average value of patents overall.

These are known problems. Over the years, researchers and investors have continually attempted to streamline patent valuation, to offer more transparent yet reliable metrics to investors. For example, it has been proposed that patent value could be tied to back-references — meaning citations as prior art by another patent — similar to scientific papers. This turned out not to be true. Without adjusting for various factors, back-references are at best weakly correlated to patent value. References mentioned in the background of a patent application are given much less ‘weight’ than, for example, in the world of academic publishing, as there is no requirement to explicitly reference earlier patents in patent applications. Furthermore, it is easy to “game the system”. Since patent applications are not subject to independent quality control in the form of peer review before filing, it is easy to “back-reference” unrelated patents within the prior art section of a later patent application by the same company, in order to boost the earlier patent’s ranking.

In a similar vein, it has been proposed to investigate the types of words used in a patent claim, following the premise that rarely-used words translate to more “original” (and therefore, more valuable) patent claims. This approach has also failed to gain traction. Companies can simply instruct their patent drafters to use unconventional words. This is easily possible, as patent drafters are not bound to any particular lexicography.

Lacking a better alternative, the status quo remains: in patent valuation, you get what you pay for. However, if metrics could be found that were inexpensive or even free to obtain, and that provided highly predictive information about the quality — or even the specific valuation — of a portfolio or patent, that would shake up the entire patent valuation industry. Investors would rejoice. And without changing the way that patent prosecution works, the number of “filler patents” and the resulting “patent bloat” could be significantly reduced.

In order to come closer to this goal, we need to ask ourselves: what are the defining features of a “filler patent”? At least two things stand out. First, “filler patents” go through more rounds of prosecution than other patents. Secondly, the independent claims of “filler patents” are longer (have higher word counts) than other patents.

Let’s look at multiple rounds of prosecution first. A “round of prosecution” means an Office action from the USPTO and the applicant’s response. It is typical for “filler patents” to go through multiple rounds of prosecution, such as six or more rounds. At each round of prosecution, the claims are tailored, so that the scope of protection of the resulting patent is whittled down until essentially nothing is left. Then the application is allowed to issue.

The other defining feature of “filler patents” is that their independent claims have very high word counts, as compared to other patents. Overall, the average word count of independent claims of granted patents has been found to be very constant over time. Average word count is relatively constant for all technology areas, as well (with IPC class C being the only major exception, having an average word count of about 30 words less than the other classes). The distribution of word count of the independent claims is presumed to be similarly unchanging.

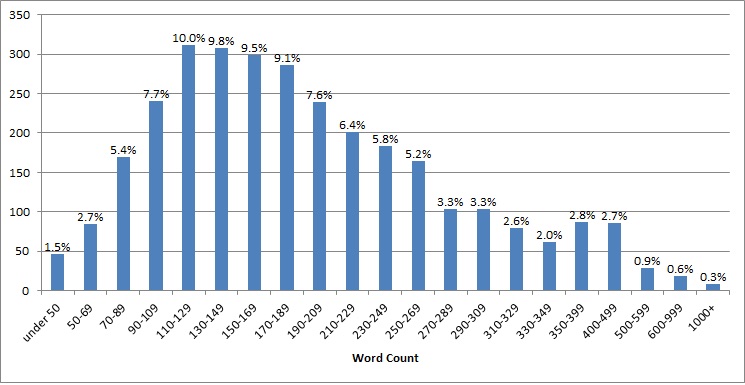

With the help of Paul Dougherty from The Patent Box, a group of 3,131 patents issued on December 27, 2016 was examined for independent claims’ word count, with the resulting distribution being shown in Figure 1. As expected, the word count of independent claims of these granted patents creates a bell-shaped curve with a right-shifted distribution. The median claim length is 173 words. Longer independent claims reflect narrower scope of patent protection. For “filler patents”, it is not unusual for the main independent claim to be 1.5 pages (about 350 words) or longer, by the time the patent is allowed to issue.

In fact, it is impossible to define the exact boundary, in terms of wordcount and rounds of prosecution, at which a patent’s scope is “guaranteed” to be factually nil. However, it is true that the higher these numbers, the more likely a patent is to be just “filler”. For the purposes of defining a cutoff, therefore, it is believed that patents with independent claims averaging over 350 words, particularly ones granted after 6 or more rounds of prosecution, are extremely likely to be “filler patents”. However, lower cutoffs (such as 250 words and 5 rounds of prosecution) could also be reflective of a high probability of a particular patent being “filler”.

“Filler patents” aside, it is also generally the case that rounds of prosecution and word count of the independent claim reflect patent quality, making it hard to “game the system” and to force an earlier allowance with a shorter independent claim, simply by prioritizing improvement of these metrics themselves. Patent practitioners are already trained to try to get an allowance with as few rounds of prosecution as possible. At the same time, patent practitioners constantly hone their skills at drafting the shortest possible independent claims that still meaningfully reflect the invention. Therefore, it is basically impossible to “game the system” and to magically bring prosecution to a swift close with a very short independent claim, unless the underlying invention really is foundational.

Here, it is important to note that prosecution rounds and claim length are closely interrelated. In order to swiftly bring prosecution to a close, an option is often to lengthen the independent claim by adding a feature. This is true especially if it is debatable as to whether the claim without that feature would be patentable. On the flip side, applicants can choose to risk extending prosecution by another round, but fight for the existing scope of protection (that is, by declining to add features to the independent claims). Patent prosecutors are already weighing these two competing goals at every step and trying to satisfy them both, in what turns out to be a tricky balancing act with no easy shortcuts to success.

The rare patent application that issues with really short independent claims after just one or two rounds of prosecution is rather likely to be a ground-breaking invention that is the “first of its kind” in a particular field or area. This is because broad scope of protection is only available for really revolutionary inventions that open up a new “space” of technology.

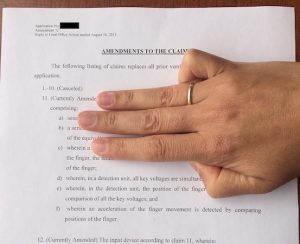

As an aside, there are some patents that issue right away with short claims because the Examiner at the USPTO failed to do a good search or examination (i.e., the patent is invalid). However, that is believed to be the exception, as Examiners are also trained to be very wary of short claims. Unofficially, some patent practitioners joke that USPTO Examiners apply the “three-finger rule”: if you can cover the independent claim with three fingers, it’s still too short to be allowed to issue.

As an aside, there are some patents that issue right away with short claims because the Examiner at the USPTO failed to do a good search or examination (i.e., the patent is invalid). However, that is believed to be the exception, as Examiners are also trained to be very wary of short claims. Unofficially, some patent practitioners joke that USPTO Examiners apply the “three-finger rule”: if you can cover the independent claim with three fingers, it’s still too short to be allowed to issue.

Taken together, the two interrelated factors of: (1) Rounds of prosecution and (2) Word count of independent claims, could serve as a much more reliable immediate indicator of quality. The information about rounds of prosecution and claim word count of granted patents is already “out there”, as the prosecution history of published applications (indicating the rounds of prosecution) and the contents of published patents (including their independent claims) are available online from the USPTO. Unfortunately, it currently requires data mining the USPTO’s public files to produce these metrics for any particular patent.

It might change the world of due diligence if these pieces of information were more accessible, for example if the USPTO provided them in the electronic file or on the cover of the granted patent itself. This would give investors outside the patent world much more reliable immediate indicators that are closely correlated to the scope — and consequently, the value — of a patent. Over time, these indicators might replace the more simplistic metric of merely evaluating patent portfolios based on size (meaning number of patents). As a consequence, companies would be incentivized to abandon patents with very high word counts and long prosecution histories, in order to keep their portfolio averages (meaning word count and rounds of prosecution) in check.

If this standard were adopted, and companies accordingly reduced the practice of “portfolio bloat”, IP practitioners would still have plenty of work to go around. In the exemplary dataset shown above, only 7.3% of patents have independent claims with 350 words or more, indicating that they are likely to be “filler patents”. Disincentivizing such “filler patents” might lead to a slight loss of business for patent law firms and the USPTO. However, this loss would be marginal, and in any case could likely be offset by the continuing positive trend in patent filings which has been seen over the past few years. Furthermore, surplus patent budget that is freed up by abandoning “filler patents” can be redistributed back into a company’s R&D. This could result in an increase in real innovation, thereby leading to more meaningful patent filings.

Also, adopting this standard would certainly not replace the work performed by firms specialized in patent valuation, as the average word count and number of rounds of prosecution of a patent portfolio only serve as a preliminary measure of the portfolio’s overall value, and cannot be translated directly into a dollar-estimate of patent value. Therefore, the demand for detailed market-based and income-based valuations of portfolios would be largely unaffected.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

12 comments so far.

Josh

August 16, 2017 04:23 pmI typically deal with smaller companies who have <10 patents in their portfolio. Comparables are extremely difficult to find as that information is typically private. I have noticed that the USPTO has added some additional features to the assignment database, like being able to click on PDFs of security agreements, financing statements, etc…I'm just wondering if the $/consideration paid for the patents is ever listed there…or, in some other resource?

Craig

August 5, 2017 09:43 amThis is a really good article, Pruning out filler patents would help the system, and finding quick ways to identify them (which could be used to affect valuations and deals) is a significant contribution. Even more so as intangible assets account for the dominant value divers for many/most public companies in their SEC filings. It is notoriously hard to assign values to intangible assets (esp patents, where the vast majority are not ‘valueable’), and the proposed 2-factor system lends itself to automation.

With respect to portfolio bloat, while I’m sure it’s an issue in some private sector companies, it pales in comparison to the Federal Lab system, especially agencies staffed with internal patent agents or attorneys to keep busy.

In this regard, it would be interesting to compare filler % (along with a measure of commercial relevance %) between selected private sector businesses (poss industry diffs?) vs Universities vs Fed agencies. Nice work.

Tesia Thomas

August 5, 2017 02:33 am@Ternary

“A patent to an independent inventor in most cases is more of a liability than an asset and has in the end a negative value.”

Exactly.

As soon as we realize our vision by selling a ton of product on which our patents are based, we compel our well funded competitors to infringe.

And then we try to fight back.

So they IPR and kill the IP.

Any money from sales goes to legal fees. We don’t make any money because we don’t keep any money.

We pay attorneys whose work product apparently sucks to get examination that supposedly sucks so we can later get infringement attorneys who suck.

The common denominator is that everything on our side sucks…except our product.

And if we didn’t have a great product then we wouldn’t be in this mess to begin with.

We’d have a nice, VALID & WORTHLESS patent.

That’s what it boils down to. The only valid patent from independent inventors is worthless.

Ternary

August 4, 2017 09:59 pmIndependent inventors are among the few applicants who are not paid for doing inventions. Their rewards are completely downstream. Researchers at universities and inventors at companies are usually salaried personnel. I won’t say that a patent is unimportant for them, but their livelihood usually does not suffer from being an inventor.

The collapse of the patent market, the efficient infringement of patents, maintenance costs and cost and effort to defend validity makes obtaining and owning a patent nowadays an extremely unprofitable business for private inventors. Just doing a patentable invention, from personal experience, takes anywhere from 500 hours up to 1500 hours and even longer. Even if all filing fees for patent applications and maintenance fees were to be free for independent inventors, then still obtaining and holding on to a patent nowadays does not make any economical sense for independent inventors in the USA and has no or very limited value. A patent to an independent inventor in most cases is more of a liability than an asset and has in the end a negative value.

Paul F. Morgan

August 4, 2017 07:29 pmBTW, a company with an effective patent maintenance fees review system should be filtering out such “filler” patents from their U.S. and foreign patent portfolios by 7.5 years from their issue dates, so having that kind of review system is something to look for in a portfolio valuation.

Edward Heller

August 4, 2017 07:28 pmAs anybody who has worked in the industry can tell you, big companies get patents to enable cross licensing. Their individual quality is not relevant. Just their quantity.

Even if a big company does not cross license, they will have a hard time enforcing any patent against a competitor because that competitor will have their own patents to assert against the company. Thus the patents held by companies in this situation are not valuable at all except in large quantities. Individual value is de minimus. None of these companies is willing to expend large amount of dollars on prosecution.

Drug companies, chemical companies and the like do not normally cross license. Their patents are all probably very valuable.

University patents — they dabble in the future. Whether an invention is going to be successful depends on whether they find licensees willing to invest. That in turn depends on whether there is a market. Complicated.

Startups is where it at — people starting small companies. Their patents protect real investment in development of new products and services. All their patents are valuable. All. (But see, IPRs.)

So, take a look at who owns the patents as a first indicator of value.

Paul F. Morgan

August 4, 2017 07:20 pmI had not heard the term “filler patents” or “filler applications” before. But I can confirm the observation that some patent applications are being filed primarily to achieve a numerical filing quota set by corporate upper or middle management for various reasons. However, I would not agree with their correlation with long PTO prosecutions. Many such applications are filed with “picture claims” passing the hand “span test” to begin with. Other applications may be amended to only have such long and narrow-scope claims after a good first action citing close prior art [rather than being abandoned] to BECOME “filler patents.” But extended expensive application prosecution and appeals for claims that could not provide effective protection of a companies own products, or income from others, is obviously not cost effective. It should not normally occur in a company with appropriate O.C. cost controls.

I certainly agree with the observations on the great difficulty of patent valuations.

Audrey Nickel

August 4, 2017 03:04 pmBob Hodges, thank you for your measured and thoughtful comment. We are working through the early stages of implementing this idea, and I definitely see your point that a high round of prosecutions can (especially in the cases you mentioned) be an indicator that the resulting patent is more valuable and not less valuable. Excellent point and I will keep that in mind as I work further on this idea.

Scott

August 4, 2017 08:16 amI agree with the strategy and the fact that the metrics given probably describe “filler patents”, but was there any analysis as to how to define “filler patents” outside of the metrics themselves? For example, data that demonstrates independently that the patents are filler, such as not filing in multiple countries, maint fee not being paid, not being highly valued in transactions, etc?

Bob Hodges

August 4, 2017 07:30 amFor the rounds of prosecution metric, there is likely to be a false positive problem for patents where it took many rounds of prosecution to get the examiner to understand the invention and finally examine the actual subject matter of the invention and where close arguments and marshaling of evidence was required in a fight for broad scope of the allowed claims. There are likely two nodes of valuable patents in terms of the rounds of prosecution metric: those that were allowed quickly because they were groundbreaking and those for which valuable scope was doggedly sought.

Edward Heller

August 4, 2017 06:59 amThere are tradeoffs if one is seeking the larger pile.

Tesia Thomas

August 3, 2017 05:56 pmYeah big companies get filler patents but the real question is qhy aren’t more filler patents being IPR’d?

Oh right. No one’s making any money from them.