The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) does much more than just conduct inter partes review trials (IPRs). Many more decisions of the PTAB are from patent examiner refusals as ex parte appeals to the Board. In these, the unsatisfied applicant requests a panel of three PTAB judges to decide whether the examiner’s rejection is erroneous or not. The USPTO rarely appeals a decision in which an Examiner is reversed, and in the past 4 years, the PTAB has designated a decision precedential only three times.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) does much more than just conduct inter partes review trials (IPRs). Many more decisions of the PTAB are from patent examiner refusals as ex parte appeals to the Board. In these, the unsatisfied applicant requests a panel of three PTAB judges to decide whether the examiner’s rejection is erroneous or not. The USPTO rarely appeals a decision in which an Examiner is reversed, and in the past 4 years, the PTAB has designated a decision precedential only three times.

What this means for the client is that the PTAB’s decision in an appeal generally is the final say—the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure forbids an examiner, after the PTAB has made its decision from entering a new ground of rejection after the decision is handed down. (MPEP §1214.04). Because of this, while very few PTAB decisions bind the PTAB itself, collectively the body of decisions reflects the current thinking of the PTAB judges in the aggregate. If the data on decisions by issue (§101, §103, §112, etc.) can be determined and if data on the legal basis of the PTAB’s decision for each issue on appeal is known, the practitioner can determine with good accuracy the percentage odds of how each issue in a particular case will be decided by the Board.

However, this data cannot be determined from the PTO’s own reported case information on the PTAB’s FOIA website. This is because of how the PTO reports the case resolution information in the FOIA website. As reported in depth here, the PTO reports a case as affirmed if all claims are rejected for at least one issue on appeal and reversed if all claims are reversed for at least one ground of rejection. A case is only reported affirmed-in-part by the PTO’s statistics if at least one claim remains standing, regardless of which legal issue ((§101, §103, §112, etc.) the claim was originally rejected. Since a large portion of PTAB ex parte appeals involve rejections over more than one ground of rejection (between 35%-45% according to this statistical estimate), this reporting process masks what the PTAB is deciding on each legal issue presented to it. Because the USPTO data does not report the outcome of each legal issue in multiple issue cases, it is impossible to collect statistically meaningful data on outcomes of specific legal issues from the data set from the FOIA website.

AIPLA’s ex parte appeals subcommittee began with the USPTO’s data and public PAIR information starting in July of 2016 and recorded the outcome (affirmed, reversed, affirmed-in-part) for each legal issue in each case along with a legal “tag” or basis which the PTAB used to make its decision. The number of tags for each issue was determined by observing the legal reasoning that the Board describes when deciding each issue and then condensing the reasoning around common observed themes. Some of these themes are familiar, but others are particular to the ex parte appeal context. For example, as Trent Ostler reported at the AIPLA Annual meeting, about 26 different tags have been identified from Board decisions for obviousness. These tags represent arguments raised by appellants, examiners, the PTAB itself.

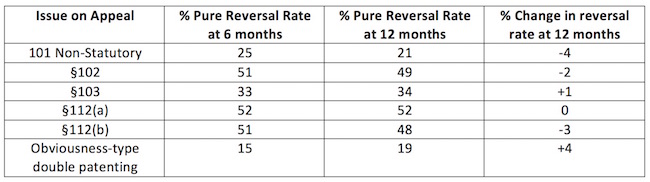

Over a year’s data has now been collected in this way. Initially, 6 months of data was analyzed to see what aggregate statistics by issue was (see article here) and then after another 6 months, the data was reevaluated again to see what changes (if any) could be observed from the Board. Table 1 describes the results as they stood in August of this year:

The first thing to note about the data is that examiners are being reversed by most issues at rates far higher than the PTO’s reporting of the statistics would indicate. The PTO statistics represent that 29.5% of ex parte appeals are reversed according to the reporting method used by the USPTO. However, by issue, the PTAB’s reversal rate varies very widely by issue. For example, for non-statutory subject matter rejections, the 12 month pure reversal rate (all claims allowed) was 21%. However, for obviousness, the pure reversal rate was 34%. Surprisingly, for anticipation, the pure reversal rate was 49%. This high reversal rate for anticipation is hidden by the USPTO’s numbers, notwithstanding that far more cases are taken on appeal for anticipation than for non-statutory subject matter. This difference really matters: if a practitioner has an anticipation issue in a patent case, then taking it to the PTAB means the odds of winning are basically 50%, all things being equal. However, the USPTO’s reported data indicates that the practitioner would have only about a 30% chance of success on any given appeal.

This observation shows that USPTO’s reporting system does more than just fail to provide customers with accurate information on their potential odds on appeal. It also fails to allow the USPTO itself to recognize that there is work to be done on the decision to issue Examiner’s Answers which result in appeal being forwarded to the PTAB. If senior level examiners like SPEs are consistently across the USPTO deciding to send anticipation cases to the Board only to lose half of them, I think all parties can agree that this not a good use of the Office’s time and resources. Either the SPEs lack the ability to accurately screen cases for anticipation even after reading the appeal brief, there are perverse incentives in place at the USPTO that favor sending losing cases to the Board, and/or we have a “training issue.” From a legal perspective, §102 is not complicated—either a single reference teaches each and every element of the claim as arranged in the claim or it does not. To have three examiners in an appeal conference still decide to issue an Examiner’s Answer in the face of the appellant’s ultimately successful arguments that a reference fails to meet this minimal standard is symptomatic of a systemic problem.

The USPTO’s data reporting method is failing to show management the existence of these issues. Whether you agree that reversal rates of 30% are “in line with expectations” or that something higher or lower across all issues is we should be seeing, the variance by issue is something that can be improved. This is particularly so when very little change was observed in the PTAB’s rate of reversals by issues from the 6 month mark to the 1 year mark. Over time, the way the PTAB is deciding cases is staying relatively constant, meaning that the examiners have been making the same kind of decisions on what cases to take on appeal on the same issues.

This data also proves that looking at today’s ex parte appeals data is predictive of the outcome a when an appeal is decided (about 17.8 months from now at current pendency)—provided the USPTO changes nothing about its current approach. Today, using ex parte appeals data, the practitioner can come up with reasonable numerical odds, all things being equal, of prevailing on a specific issue on appeal using the PTAB’s jurisprudence. Using the identified tags for the grounds of rejection in the dataset further allows the practitioner to drill down using the database of decisions and compare similar cases’ facts to make a truly educated, data driven decision on how the legal issues in a particular case would be decided by the Board where a decision made today.

However, this ability to use ex parte appeals data has not come from the USPTO—rather it has been the folks at the AIPLA ex parte subcommittee that have made it possible to find what was hidden but always present in the PTO’s data. If the USPTO changes nothing about its current reporting approach, then it will to lack the ability to see and resolve systemic problems with the appeals and examination process. However, the ex parte appeal data available now means that clients do not have to also remain in the dark.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

BRI

November 14, 2017 09:11 amFor the high level of 102 reversals, how many turn on the broadest reasonable interpretation? Could it be that examiners are using a broadest possible interpretation that is overturned, which leads to no anticipation?

Curious

November 14, 2017 07:58 amThanks for the information. What I would love to see published is how the numbers at the PTAB (formerly the BPAI) have changed over the last 20 years. I’ve already seen the numbers, but it would be really informative (for everybody else) to show how the Board has slanted heavily towards the Examiner over the years.

BTW — the difference in 102 and 103 reversal/affirmance rates can be explained, at least in part, by the PTAB having lots of tools to ignore both arguments and limitations when it comes to 103 rejections.