There is great variability with respect to patenting cancer innovation. Cancer patent application allowance rates range from 20.5% to 100.0%, with even similarly situated Art Units showing a wide disparity.

During the 2016 State of the Union Address, a national “Moonshot” initiative was proposed to bring about a decade’s worth of cancer-focused advances in five years. Stated objectives were to make more therapies available to more patients, while to also improve our ability to prevent cancer and detect it at an early stage. In order to help achieve the Cancer Moonshot’s goals, a White House Cancer Moonshot Task Force was established to focus on accelerating research efforts and breaking down barriers to progress by enhancing data access, and facilitating collaborations with researchers, doctors, philanthropies, patients, and patient advocates, and biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.[i]

During the 2016 State of the Union Address, a national “Moonshot” initiative was proposed to bring about a decade’s worth of cancer-focused advances in five years. Stated objectives were to make more therapies available to more patients, while to also improve our ability to prevent cancer and detect it at an early stage. In order to help achieve the Cancer Moonshot’s goals, a White House Cancer Moonshot Task Force was established to focus on accelerating research efforts and breaking down barriers to progress by enhancing data access, and facilitating collaborations with researchers, doctors, philanthropies, patients, and patient advocates, and biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.[i]

In response to the Moonshot Initiative and at the behest of the White House Cancer Moonshot Task Force, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) launched two programs directed to harnessing the power of patent data and accelerating the process for protecting intellectual property associated with cancer immunotherapy breakthroughs. The first program included the USPTO release of Cancer Moonshot Patent Data sets and a “Horizon Scanning Tool” to build rich visualizations of intellectual property data and combine them with other economic and funding data. The Cancer Moonshot Patent Data sets were generated by applying classification-based and keyword-based queries to identify cancer-specific patents and patent applications spanning the 1976 to 2016 period (n=260,353). The second program included the USPTO establishing a Fast-Track Review entitled Patents 4 Patients, which is a free and accelerated pilot program that aims to cut in half the time it takes to review patent applications in select fields of cancer therapy (in less than 12 months) for cancer treatment-related patents.[ii]

The UPSTO’s involvement in this initiative to accelerate research and development efforts is consistent with the agency’s long-standing purpose to encourage the development of new inventions. More specifically, the patent system was designed to encourage the public disclosure of new inventions by providing a government-granted temporary monopoly on the commercial use of any novel and non-obvious invention.[iii] The temporary monopoly gives the inventor a chance to recoup investments made during the development of an invention and generate profit, and the public disclosure is intended to inspire others to research and develop enhancements or alternatives to the patented invention. In fact, it has been demonstrated that innovation is driven primarily not by genius or coincidence but rather by economic markets and the expectation of profit that can be gained by securing patent rights to new technologies.[iv]

This logic would suggest that the patent system has and could continue to promote cancer advancements to help achieve the stated objectives of the initiative. However, it is essential to consider one important variable: only a fraction of patent applications are allowed to issue as a patent, as the mere existence of the USPTO does not guarantee that a discovery can be patented. Rather, there are various statutes that define the requirements for securing a patent, such as requiring that the patents include claims that are new and non-obvious over prior art. To effect these requirements, each patent application is assigned to one of thousands of patent examiners at the USPTO, who evaluates the application and applies interpretations of the requirements. Ultimately, the examiner either allows the patent application to issue as a patent, or the entity applying for the patent abandons the application. Thus, the present state of intellectual property law and unpredictable factors such as examiner training could impact the prospects that a patent application will be allowed.

If we accept the idea that innovation is promoted by availability of patent protection, we would also expect that innovation efforts would also be tied to a predicted likelihood that a patent application will be allowed. For example, if an entity is using a risk-vs.-reward analysis to determine an amount of human or monetary resources to devote on research and development, the determination would seemingly be highly tied to a confidence as to whether the entity can obtain allowance of a patent application. Yet making an informed decision in this regard is particularly difficult if the patenting prospects are unknown or unpredictable.

The Cancer Moonshot Patent Data set provides an opportunity to investigate what the patenting prospects are for cancer-related innovations. We analyzed a subset of the Data Set for which prosecution and status data was available via LexisNexis® PatentAdvisorSM, which largely corresponded to applications filed after November 29, 2000.[v] (n=64,341)

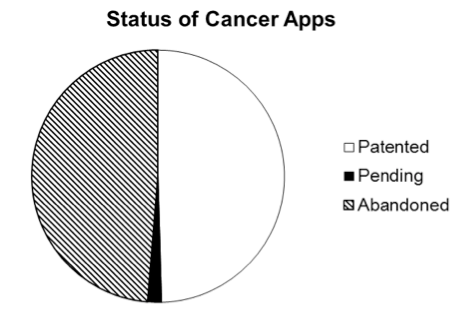

Figure 1 shows the status of the cancer-related applications in our data set. The vast majority (98%) have reached a final disposition of being either patented[vi] or abandoned. Of these finally disposed applications, 50% of the applications were or are patented. Across all applications, the average percentage of finally disposed applications that were or are patented is 52.4%.[vii]

Figure 1. Statuses of All Analyzed Cancer Applications. As described in the text, we analyzed a subset of the Cancer Moonshot Patent Data that had publicly available prosecution and status data. The distribution of statuses of these applications is shown.

Previous studies have shown that patenting prospects are not consistent throughout the USPTO.[viii] More specifically, substantial variation of rates of allowing patent applications to issue as patents (“allowance rates”) has been observed across “art units” at the USPTO. An art unit corresponds to an examining unit (group of examiners) that corresponds to a particular subject area. In response to filing of a patent application, the USPTO assigns it to an “art unit” that is to correspond to the technology of the desired protection. There are hundreds of art units at the USPTO, and there is some overlap in terms of technology area of the art units.

One hypothesis is that the variability of allowance rates indicates and is accounted for by an actual difference in allowance probabilities across technology areas. For example, it is possible that semiconductor technology is evolving so quickly that there is less prior art that may potentially block a new application on the grounds of obviousness or lack of novelty as compared to mechanical technology. As another example, recent case law has interpreted a patent-eligibility statute in a manner that makes it more difficult to patent some types of software technology.[ix]

Another hypothesis is that the variability of allowance rates represent a consistency issue, explained merely by different examination tendencies across supervisors of art units and/or examiners. Under this hypothesis, if two applications similar in terms of technology area and inventiveness were assigned to different art units or examiners, a different examination result may be obtained. Though it would be difficult or impossible to conduct this precise analysis, population analysis of a set of patent applications relating to a similar technology may be informative. The USPTO-identified Cancer Moonshot Patent Data set provides this opportunity.

We were able to identify the art unit assignment and status of each patent application in our data set through LexisNexis® PatentAdvisorSM . The applications were assigned to 303 different art units, and the number of cancer patent applications assigned to each of these art units ranged from 1 to 4120.

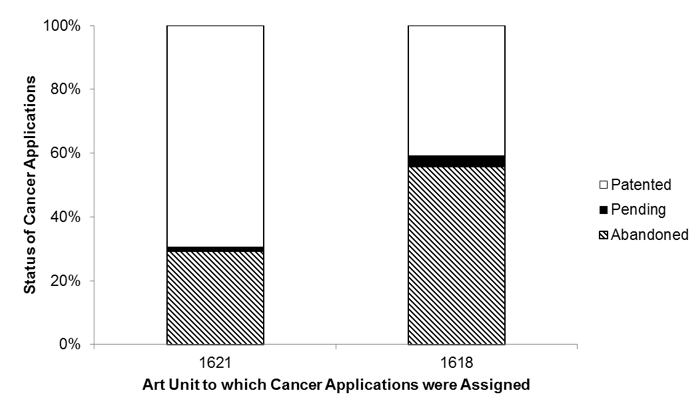

Several of these art units are identified by the USPTO as relating to very similar technology areas. For example, each of Art Unit 1618 and 1621 are identified as relating to “organic compounds – part of the class 532-570 series.”[x] However, as shown in Figure 2, the patenting probability is markedly different between these two art units. Specifically, amongst the finally disposed applications (which excludes the pending applications), 70.5% of the cancer patent applications assigned to Art Unit 1621 were patented, while only 42.3% of the cancer patent applications assigned to Art Unit 1618 were patented.

Figure 2. Statuses of Cancer Applications Assigned to Two Exemplary Art Units. Each bar in the stacked bars shows the percentage of cancer applications assigned to the art unit identified along the x-axis that have a status as identified by the shading. (n=956 for Art Unit 1621 and n=1153 for Art Unit 1618.)

This discrepancy is also observed when considering all patent applications and not just cancer patent applications. Specifically, the overall allowance rates of Art Units 1621 and 1618 are 70.5% and 39.2%, respectively.

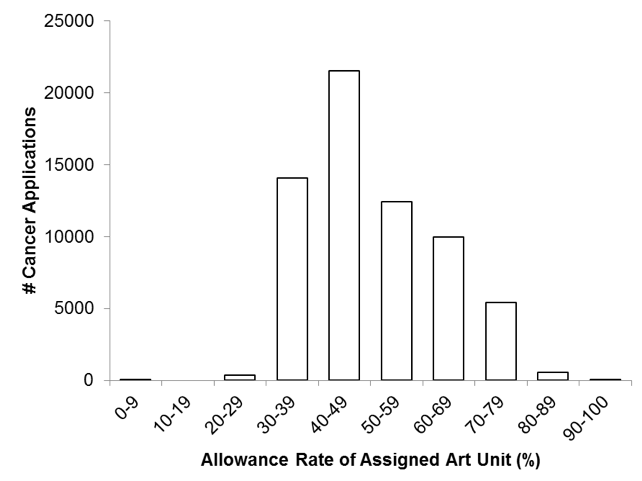

Thus, this particular comparison suggests that, despite the shared cancer focus, cancer applications are subjected to a similar inconsistency in patent prospects as has been previously reported in a general context. Figure 3 shows the distribution of cancer applications assigned to art units within various allowance-rate bins. As illustrated, a substantial portion (22%) of the cancer applications were assigned to art units with relatively low allowance rates of 30-39%, while another substantial portion (16%) of the cancer applications were assigned to art units with much higher allowance rates of 60-69%.

Figure 3. Distribution of Cancer Applications relative to Art Units’ Allowance Rates. Each assessed cancer application was assigned to one of ten bins, based on an allowance rate of an art unit to which the application was assigned. The count of applications in each bin is shown.

To further investigate, we identified art units in which at least 20 cancer applications were assigned, which resulted in an identification of 98 art units. We then compared the allowance rate (number of patented applications divided by the number of patented or abandoned applications) of the cancer applications as compared to the general allowance rate of the art unit as identified in LexisNexis® PatentAdvisorSM data.

As shown in Figure 4, the cancer-application allowance rates are highly correlated with the general-application rates (R = 0.83, p < 0.01). The cancer-application allowance rates range from 20.5% to 100.0% in various art units (with the general allowance rate of these art units ranging from 25.7% to 97.8%). Thus, the probability of securing patent protection on a cancer-related innovation exhibits marked variability and appears to be highly dependent on art-unit assignment.

Figure 4. Per-Art-Unit Allowance Rates of Cancer Applications versus of All Applications. Each point resents an art unit. The y value identifies the percentage of analyzed cancer applications assigned to the art unit that were/are patented as opposed to being abandoned. The y value identifies the general allowance rate for the art unit (not specific to cancer applications).

Given that an applicant has limited control of to which art unit an application will be assigned, this broad range of allowance rates indicates that it would be quite difficult for an inventing entity to predict whether a patent is obtainable. This is particularly problematic if the entity is using a risk-vs.-reward analysis to determine an amount of human or monetary resources to devote on research and development. For example, the cost of drug development has been estimated to be as high as $1.3 billion.[xi] Whether and/or an extent to which a company embarks on an effort to develop a drug would seemingly be highly tied to a confidence as to whether a drug can be patented so as to fend off generics. Yet making an informed decision in this regard is particularly difficult given the above-presented large spread of allowance rates.

But the uncertainty does not even end here. Beyond the variability and uncertainty observed in the probability of securing patent protection across art units at the USPTO, previous studies have also shown that patenting prospects are highly dependent on government administration since the law leaves many things to the discretion of the Director of the USPTO.[xii] More specifically, substantial variation of overall allowance rates (across all art units) has been observed from one administration to the next administration. For example, there was a significant drop in allowance rates in 2008-2009 under Jon Dudas followed by a rapid rise in allowance rate once David Kappos took over as Director. Allowance rates continued to rise under Michelle Lee albeit not as dramatic as the rapid rise seen between the Jon Dudas and David Kappos administrations. More recently, the U.S. Senate on February 5, 2018 confirmed Andrei Iancu as the next Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Although it is still too early at the time of writing this article to know how Andrei Iancu is going to direct the examining corps or whether his directives will improve the variability and uncertainty observed across art units, a change in administration at least provides an opportunity in this respect and Andrei Iancu and the new administration can and should prioritize this effort.

In conclusion, conquering cancer remains a national priority. The USPTO has attempted to contribute to this worthy goal through multiple new programs. However, perhaps one of the largest contributions that the USPTO could provide is to address an issue that affects a more general group of innovators by improving examination variability and uncertainty. Until that is accomplished, it is important to recognize the answer to the question “What is the probability of a cancer-related patent application being allowed in the U.S.?” is not a number. It’s a broad distribution.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of their employer, Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP., or its clients.

_______________

[i] The White House – President Barack Obama, Fact Sheet: Investing in the National Cancer Moonshot (Feb. 1, 2016), available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/01/fact-sheet-investing-national-cancer-moonshot (last accessed Jan. 30, 2017).

[ii] U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, Teaming up to Cure Cancer (June 29, 2016), available at: https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/teaming-cure-cancer (last accessed Jan. 30, 2017).

[iii] Kenneth L. Sokoloff & B. Zorina Khan, Intellectual Property Institutions in the United States: Early Development and Comparative Perspective (Prepared for World Bank Summer Research Workshop on Market Institutions, Washington, DC July 17-19, 2000), available at: www.dklevine.com/archive/sokoloff-kahn.pdf (last accessed Jan. 30, 2017).

[iv] Kenneth L. Sokoloff & B. Zorina Khan, Schemes of Practical Utility: Entrepreneurship and Innovation Among “Great Inventors” in the United States, 1790-1865 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research Working Paper Series on Historical Factors in Long Run Growth, Historical Paper No. 42, 1992).

[v] Beginning in 2001, data corresponding to patent applications were generally published after expiration of an 18-month period following the earliest effective filing data. Data is not published if, for example, a non-publication request is received (which indicates that foreign filing is not to be sought) or an application is expressly abandoned prior to the expiration of the period.

[vi] For purposes of this study, we characterize “patented” applications as including not only applications that are currently patented but also applications that were patented but are now expired due to normal patent term expiration or as a result of failure to pay maintenance fees.

[vii] U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, Performance and Accountability Report for Fiscal Year 2016 (Nov. 14, 2016), available at: https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/USPTOFY16PAR.pdf (last accessed Feb. 6, 2017).

[viii] See Gaudry, Grab & McKeon, Trends in Subject Matter Eligibility for Biotechnology Inventions, IP Watchdog (July 12, 2015), https://ipwatchdog.com/2015/07/12/trends-in-subject-matter-eligibility-for-biotechnology-inventions/id=59738; see also Kate Gaudry, Post-Alice, Allowance are a Rare Sighting in Business-Method Art Units, IP Watchdog (Dec. 16, 2014), https://ipwatchdog.com/2014/12/16/post-alice-allowances-rare-in-business-method/id=52675.

[ix] See Kate Gaudry, Post-Alice, Allowance are a Rare Sighting in Business-Method Art Units, IP Watchdog (Dec. 16, 2014), https://ipwatchdog.com/2014/12/16/post-alice-allowances-rare-in-business-method/id=52675.

[x] U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, Classes Arranged by Art Unit: Art Units 1611-1763, available at: https://www.uspto.gov/patents-application-process/classes-arranged-art-unit-art-units-1611-1763 (last accessed Jan. 30, 2017).

[xi] Joseph A. DiMasi & Henry G. Grabowski, The Cost of Biopharmaceutical R&D: Is Biotech Different?, 28 Managerial & Decision Econ. 4-5, 469–79 (June-Aug. 2007).

[xii] See Dennis Crouch, USPTO Allowance Rate, Patently-O (Nov. 2, 2016), http://patentlyo.com/patent/2016/11/uspto-allowance-rate-2.html and Dennis Crouch, Patent Application Outcomes: Rising Allowances and Falling Abandonments, Patently-O (Dec. 6, 2016), http://patentlyo.com/patent/2012/12/patent-application-outcomes-rising-allowances-and-falling-abandonments.html.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

5 comments so far.

Joachim Martillo

March 12, 2018 08:25 amAccording the USPTO description,

1620 examines applications that pertain to organic chemistry while

1610 examines applications that pertain to organic compounds: bio-affecting, body treating, drug delivery, steroids, herbicides, pesticides, cosmetics, and drugs.

From the titles it makes sense that a non-biologic goes to 1621 while an application that involves a treatment of some sort goes to 1618.

The titles do not suggest an “old v. new” distinction.

An application pertaining to a treatment might receive a Mayo rejection. I have to go back and check, but I believe USPTO guidance contained in the MPEP differs significantly from the apparent thinking of the judges on the CAFC.

I discuss the oral argument in Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. West-Ward Pharmaceuticals (Case Nos. 16-2707 and 16-2708), December 5, 2017, in Administer–”Do Standard Detection”–”Modify Administration” Method Claims and 35 USC § 101 Eligibility Analysis (Part I: Vanda and Prometheus).

[The reader can skip the introduction. I was whining because I had just suffered five months of really bad vertigo only to be burnt out of my apartment.]

The oral arguments tell me that the CAFC gives extra scrutiny to a new method of treatment that combines an old method of treatment with detection of a natural phenomenon. Because claiming a natural phenomenon is a judicial exception to eligibility, there probably is no prior art pertaining to the natural phenomenon, and no obviousness rejection can be made.

Instead SCOTUS holds that such claims, whose specified metes and bounds encompass a natural phenomenon and something that would otherwise be eligible, must be rejected under the reasoning of the Alice-Mayo Test.

If the MPEP follows the reasoning of West-Ward Pharmaceuticals, we may seeing rejections of the patent eligibility of cancer drugs that are not only promising but also completely eligible for patent protection.

Shannon Zhang

March 7, 2018 09:43 pmI really like these data driven posts and appreciate forrays into the chemical domain. As I understand the inner workings of the PTO the difference between an application being assigned to 1618 or to 1621 lies in the novelty of the drug. If the drug is “new” and not a biologic the case goes to 1621. If the drug is “old” the case goes to 1618. I’m not surprised by any of the above reported numbers and certainly hope the authors will dig a bit deeper into the data and publish their findings.

Joachim Martillo

March 6, 2018 09:04 pmI guess I should feel complimented, but it seems sans goût to plagiarize in an Intellectual Property (IP) forum.

Anyway, I have seen some evidence that the USPTO continues to run SAWS-like unlawful secret quality assurances.

It is worthwhile to revisit the SAWS “cure” category from page 12 of the SAWS FOI document that Kate Gaudry obtained.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1su-AVd0NGMuMgPsFg30pkp2nbXh0hzrk

Obviously, certain cures are extremely valuable.

Because of the internal mechanisms of the USPTO, I could easily envision that a crooked senior USPTO official sells a valuable cure to friends in the pharma industry and enters into a secret quality assurance database those flags, which guarantee

1) that the examiner dutifully rejects, rejects, and rejects the application and

2) that PTAB APJ clowns then uphold the groundless rejections.

satori

March 6, 2018 03:11 amI would have entitled the article something like “The Corruption Infecting the US Patent System Since the GATT Changes (1995), not China’s IP Policies, is the Reason Behind America’s Decline in Global Competitiveness. A lot of US patent system problems would vanish if the US reverted to a system of first inventor, secret patent application, and 17 year term from date of issue. Of course, a good number of senior USPTO officials and APJs need to exchange three-piece suits for government issued orange jumpsuits. I would modify the rules giving an inventor an invention date before the earliest priority filing date if and only if he can demonstrate a (diligently maintained) blockchain ledger from the date of conception. The USPTO should offer a blockchain-based virtual engineering notebook service.

Warren Woessner

March 1, 2018 11:30 amDid you discriminate between art units handling claims directed to diagnostic methods to detect or stage cancer, and claims to methods of treating cancer? Diagnostic claims are almost always rejected under s. 101.