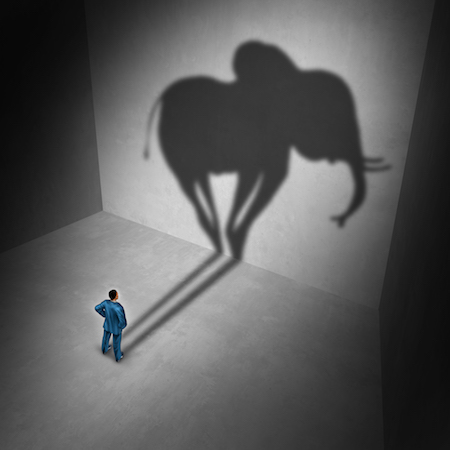

“The uncertainty created by the Supreme Court with respect to patent subject matter eligibility has few bounds – even impacting the most celebrated inventions of our most honored inventors.”

On the chance it is not apparent, the title of this article is a play on words. 35 USC §101 is the US statute that addresses what constitutes patent eligible subject matter. The number “101” is also used in university course offerings to connote courses that introduce one to the basics of a topic (as in “chemistry 101”). One might think that, like an introductory course introducing one to the basics of a topic, 35 USC §101 would be readily understood, providing clear groundwork regarding what is, and what is not, patent eligible.

On the chance it is not apparent, the title of this article is a play on words. 35 USC §101 is the US statute that addresses what constitutes patent eligible subject matter. The number “101” is also used in university course offerings to connote courses that introduce one to the basics of a topic (as in “chemistry 101”). One might think that, like an introductory course introducing one to the basics of a topic, 35 USC §101 would be readily understood, providing clear groundwork regarding what is, and what is not, patent eligible.

And that very reasonable assumption is completely wrong. Not because the wording of 35 USC §101 is unclear, but rather Supreme Court decisions applying Section 101 have created a great deal of uncertainty regarding what is patent eligible subject matter.

Here are the basics about patent subject matter eligibility. 35 USC §101 reads:

Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

That should more or less be all one needs to know. But it isn’t. The Supreme Court long ago created its own exceptions to patent eligibility: laws of nature, natural/physical phenomena, and abstract ideas (these exceptions do not appear anywhere in the statute and are thus not found in “the conditions and requirements of this title” referred to in the final clause of 35 USC §101). However, the Court has never articulated a clear, satisfactory test for determining whether a claimed invention is subject matter eligible or whether it instead falls within one of the exceptions. In recent years, as the Supreme Court has confronted new fields of invention, it has reacted by expanding exceptions to patent eligibility and thus further curtailing protection for many cutting edge innovations in biotechnology and software.

Much has been written about the shortcomings of the Supreme Court test for subject matter eligibility and its negative impact that I don’t need to list here.

Patent system participants concerned about the current state of patent subject matter eligibility have been collecting examples of how 35 USC §101 jurisprudence has undermined certainty and protection for worthy inventions. These include, but are not limited to, conflicting Federal Circuit subject matter eligibility decisions regarding patents covering very similar technologies, and patents found to be ineligible in the US, but eligible in other countries.

One way to examine the impact of the Court’s holdings in the area of patent subject matter eligibility on the US patent system is to look back at some of our most celebrated patents to project how they might have fared in the current state of confusion. The patents discussed below are all landmark inventions and were conceived by inventors inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF). Would these ground-breaking inventions, that helped set the course of humanity, be patentable today?

Some of my findings:

Consider the work of Leonard Adleman, Ronald Rivest, and Adi Shamir. They are to be inducted into the NIHF this year for US Patent 4,405,829 relating to RSA (an acronym formed from the first letter of the last names of the inventors) cryptography used in many Internet-based transactions. What would the Supreme Court make of the claim below in their patent? Is the claimed invention “abstract”? If so, is it transformed into something “significantly more”?

23. A method for establishing cryptographic communications comprising the step of:

encoding a digital message word signal M to a ciphertext word signal C, where M corresponds to a number representative of a message and

0?M?n-1

where n is a composite number of the form

n=p•q

where p and q are prime numbers, and

where C is a number representative of an encoded form of message word M,

wherein said encoding step comprises the step of:

transforming said message word signal M to said ciphertext word signal C whereby

C=Me (mod n)

where e is a number relatively prime to (p-1)•(q-1).

Consider the work of Barbara Liskov. She was inducted into the NIHF in 2012 for US Patent 6,671,821 relating to fault tolerant programming languages and system design. The Hall of Fame web site actually refers to “data abstraction” in describing her work! Perhaps an alleged infringer might use these words to challenge the eligibility of the patented invention.

Consider the work of the very famous Steve Jobs. He was inducted into the NIHF in 2012 for US Patent 7,166,791 relating to the iPod user interface. Is a portable device interface of “user selectable items” (as claimed) “abstract”? What are user selectable items? Are user selectable items “necessarily abstract” (or not)? How does one know?

Consider the work of Dov-Frohman-Bentchkowsky and Ross Freeman. The former was inducted into the NIHF in 2009 for US Patent 3,744,036 relating to electrically programmable read-only memories and the latter was inducted into the NIHF 2009 for US Patent 4,870,302 relating to field programmable gate arrays. How would the Supreme Court view the programmable nature of these devices today? “Abstract”? “Transformative”? Why or why not?

Consider the work of James Wynne, Rangaswamy Srinivasan, and Samuel Blum. They were inducted into the NIHF in 2002 for US Patent 4,784,135 relating to excimer laser surgery – the underpinning for the procedure later developed in collaboration with an ophthalmic surgeon that became known as LASIK. Is the precise etching of living tissue with minimal collateral damage to the surrounding area a “natural phenomenon”?

Need I go on? The point is that at first blush it’s not readily clear whether these patents would be found subject matter eligible, demonstrating that the uncertainty created by the Supreme Court with respect to patent subject matter eligibility has few bounds – even impacting the most celebrated inventions of our most honored inventors. I am not arguing that the cited inventions are or should be eligible or ineligible, or have or lack merit. Perhaps a complete reading of the patents might resolve some of the eligibility issues raised by the current Supreme Court jurisprudence, but if we cannot determine with reasonable certainty how all of these inventions would fare if judged under recent Supreme Court case law, then no one can truly teach Patent Subject Matter Eligibility 101.

And now, as we embark into the unknown with nearly limitless computing power in the fields of quantum computing, artificial intelligence, cyber security, medical diagnostics, and biotechnology, and in fields that have not even been thought of yet, do we really want to continue with a weakened patent system that throughout our history played such a key role in promoting “the Progress of Science and useful Arts” to bring us to this technologically-advanced state?

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

31 comments so far.

Ternary

May 11, 2018 10:31 amNight. Thanks for pointing out http://www.717madisonplace.com/?p=9768 @1. It has not received the attention it deserves. The discussion is so unbelievably bizarre. If could be part of Waiting for Godot. A piece of absurd theater.

I cannot get my head around adult people labeling “transmitting, receiving and processing of signals” as abstract ideas. And nobody says, “but that is absurd.” Of course in re. Nuijten the same court determined that those devices were patent eligible, but those were more enlightened times I suppose. It sounds like a dark age discussion about religion wherein an “abstract idea” is an abhorrence, a concept of the devil, a dangerous idea that you best don’t appear to support. Like communism in the 1950s. It is everywhere!! Boohoo…

Night Writer

May 11, 2018 07:56 am@29 Ternary Even worse, there is no guarantee that an issued patent will survive an Alice challenge.

I absolutely agree with this. And I think the same is true with preponderance of the evidence and KSR. And competent fact finder can invalidate any claim with KSR and the preponderance of the evidence.

Ternary

May 10, 2018 03:45 pmPaul @27 a patent application specification is nothing like “what is needed in journal articles or technical reports.”

You seem to imply that if we all did a little more our best, then the 101 issue can be circumvented. You are missing the point of this article, which is that “Supreme Court decisions applying Section 101 have created a great deal of uncertainty regarding what is patent eligible subject matter.” No matter how detailed or “high quality” the specification is, there is little predictability as to the patent eligibility of the claimed invention. Even worse, there is no guarantee that an issued patent will survive an Alice challenge.

If you were offered to buy a house with the type of “security” on the deed as inventors get on their patents, you would probably walk away from the deal. And that has nothing to do with the quality of the house.

Marc Ehrlich

May 10, 2018 08:03 amWell done Manny! This is a particularly poignant way to highlight the chaos wrought by recent 101 jurisprudence.

It demonstrates that when courts attempt to create tests that engage in “line drawing” between eligible and ineligible inventions – the pace of technological change renders the lines obsolete the moment they are drawn. Our judiciary has had more than enough time to realize the folly of this approach and yet has made no attempt (not even a dissenting judge in Alice) to depart from this dangerous path.

Paul Cole

May 10, 2018 05:35 am@ Eric Berend

I am loath to spend time this morning on further comments, but common sympathy demands an answer.

The drafting of patent specifications is a team effort: it is not just the efforts of the attorney given the notes of the inventor that matter but the combined efforts of the two working together to produce the patent specification in the best possible form. Only this combined effort will produce a quality document, and for that purpose it is helpful if the inventor learns a little of what the attorney is required to do and will then be in a better position to help.

We should remember William Ernest Henley who wrote Invictus (after which the well-known games are named): “Beyond this place of wrath and tears Looms but the Horror of the shade, And yet the menace of the years Finds, and shall find, me unafraid. It matters not how strait the gate, How charged with punishments the scroll, I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.”

Supine victimhood does not give rise to admiration or deserve sympathy. It is up to the inventor to do his or her best and work as a committed and skilled member of the team. Some knowledge of what it needed for patent specifications is helpful, and it is not so different from what is needed in journal articles or technical reports. The position is not hopeless: the present legal problems can be circumvented with effort and skill of the combined team and realistic enforceable patents can be obtained.

Ternary

May 9, 2018 04:47 pmInventors in the field of encryption/blockchain/security have to constantly worry about their inventions being patent eligible. Not only if their invention is patent eligible now, but if their earlier issued patent will be invalidated under new rules. It is educational to read the office actions in US 9,716,590 to Gentry (of IBM actually) on homomorphic encryption (this allows computations to be performed on encrypted data).

The Examiner is not unsympathetic to the application and actually points to a solution to overcome the 101 rejection. One reason for rejection of the application over Alice is that encryption is well known and was applied in the time of the Romans. What does that have to do with anything? Food-processing, glass-blowing, weaponry, weaving etc were also known by the Romans. That doesn’t make it “abstract”.

Almost all ancient encryption methods were manual and alphabetic ciphers and are not secure in machine encryption. Secure ciphers (or secure key generation for ciphers) can only be generated by computers as these keys such as in RSA and Diffie Hellman consist of hundreds of digits. You literally cannot manually break a secure key in the presumed lifetime of our universe. Romans did not have the mathematics nor the machines to generate these keys, let alone attack these methods.

The well known Enigma cipher machine involved a series of patents. (http://www.cryptomuseum.com/crypto/enigma/patents/index.htm). These all relate to mechanical devices and were patent eligible. The steps of these machines can be performed by computers and most likely would be, for that reason if implemented on a computer now be patent ineligible. Madness.

I listened to http://www.717madisonplace.com/?p=9768 as suggested by Night Writer. One of the Judges asked the very pertinent question as to why a toy that did not exist before is not patent eligible? No acceptable answer was given. Only that other similar devices were also considered an abstract idea. And that the new toy merely incorporated the abstract idea of a technology (transmitting, sensing, receiving, processing, actuating). More madness.

Inventors/organizations/companies who rely on patent protection are confronted with a dilemma to disclose and face a considerable risk to have an invention placed in the public domain against their wishes due to post-issuance invalidation. You have no idea what you will run into as to validity over 101, not only in the Office, but especially post-issuance.

I must assume that an organization like IBM involved in critical areas like “quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and cyber security” is seriously assessing if filing a patent application or even disclosing in an article in certain fields is worth the risk of losing exclusivity over an invention due to the unpredictability of the patent system.

I suspect that IBM for that reason has stopped or at least postponed publishing of certain developments. Or even has stopped certain developments completely.

The above article is a serious warning about the risks posed by a weakened patent system. It repeats what independent inventors have been saying for years now. For Manny Schecter of one of the world’s leading technology and research companies and the leading patent filer to write about the risks of our chosen (or rather dictated) direction is a serious and deliberate warning that we are on the wrong track. The establishment may not care about independent inventors. Hopefully, they give greater credence to IBM.

Joe Kincart

May 9, 2018 04:01 pmWell said Mannie. Thank you for taking the time to generate such a cogent point.

Eric Berend

May 9, 2018 02:30 pmShould it be the province or domain of inventors to concern themselves with such aspects of the invention process as jurisprudence, various realms of the U.S. patent regime such as PTAB, CAFC, SCOTUS; and so forth? Do we as a society, require the same of authors?

What happened to the Founding Fathers’ explicit parity of peerage of these creators of private property, legitimately induced towards public disclosure by the private-public bargain in Article 8 and expounded upon in its very intent, in The Federalist Papers Numbers 10 and 35?

Why must an inventor undertake a substantial study and a *de facto* partial practice of law, to the extent expected of paralegals at the least; merely to gain a sliver of an iota of a chance of success at defending their rightful intellectual property?

Do we mock ‘foolish, idealist’ inventors at their “delusion” of potential for success, for those who do not also prepare to comprehend and prosecute their interests with the experienced adroitness of a practicing attorney?

Oh, do we not? Don’t we?

For inventors, the truth really, REALLY stinks; right about now: we don’t see any attorneys, legislators or jurists being mocked, excoriated and exploited for their inability to perform a prognosis or surgery upon themselves; having nearly universally, NOT at least partially trained themselves in the practice of a medical Doctor, in circumstances of medical need or convention.

Where these so-esteemed lordlings of our ‘Great Society’ are concerned, reliance upon a different professional, is to be expected, respected and relied upon. Similarly so, for the authors.

Not so, for the inventors.

Perhaps not so eloquently as what I have attempted to express in my own regard, I may daresay; but the uncomfortable truth is: angrydude was right, all along. Inventors, precisely because of what I describe here, may take some time to slowly and reluctantly believe the U.S. patent opportunity for credibility and wealth, is dead and gone. However, this perception in general, is inevitable.

They – WE – were told “by the professionals”, to trust attorneys to handle the legal process part of invention practice for inventors, to TRUST THE DESIGNATED PROFESSIONAL – a proper and normally correct separation of concerns. Now that nearly the entire forest is burned down around us, so to speak; you’ll forgive the inventors for losing trust almost entirely.

Judges, legislators and attorneys: your recent seeming ‘change of tune’, cannot bear veracity of earnest integrity; as, the “music” you’re playing sounds so much like the same deceptive drivel to the vast majority of (now largely ‘former’) inventors.

Now, let us see going forth, whether you all as a combined overclass, will continue the mistake of not only a ‘beating a dead horse’ – but “beating” the WRONG ‘horse’.

Perhaps by the time the next generation of inventors rolls around, you’ll have a fighting chance for fomenting a legitimate appeal for participation in the U.S. patent prosecution process, once again.

Perhaps.

Bemused

May 9, 2018 10:38 amI think SCOTUS mixed up the standards for obscenity and patent subject matter eligibility. Judges know what is (or isn’t) patent subject matter eligible when they see it. SCOTUS needs to be stripped of appellate jurisdiction over patent cases.

angry dude

May 9, 2018 09:34 amRSA algorithm is the backbone of all e-commerce and zillions of other things

It would most certainly be held patent ineligible matter by the current uspto, scotus, cafc and district courts – all of them

sucks to be an inventor these days…

Anon

May 9, 2018 08:28 amAnon2,

Your logic applies with equal force to the converse of negative phrasing.

The path – the only path – to remove the influence of the Court is to remove the Court itself: jurisdiction stripping.

Anon2

May 9, 2018 07:36 amAnon@14

I don’t think Patent legislation can contain any generalized wording which is defined elsewhere , which can sustain a judicial law writing spree.

Any section 101 which refers in general to “new” or “invents” or “process”, and tries to define or restrict these terms is likely still leaving the door open a crack.

Instead of a ladder of inclusive open ended abstractions, defining when a patent is to be granted, I wonder if the opposite approach, is possible.

Since, the positive presence of any term provides some license to twist it, perhaps replacement of any abstract term explicitly with its detailed definition would be part of the solution. Instead of a ladder of abstractions one is provided with less easy target of explicit detail (less subject to twisting?).

Instead of being granted inclusively when requirements are met, state that the patent IS to be granted UNLESS, and ONLY unless, the application, or claim does NOT describe and claim [detailed definition of the requirements].

Or is it simply impossible to fortify the LAW against the men and women of the COURT?

Paul Cole

May 9, 2018 05:02 am@ 16 and 17

If you look at Night Writer’s final sentence, although reality may not be quit as harsh as he suggests, he is pointing to the same problem that I have been writing about.

Dan Bestor

May 8, 2018 10:21 pmManny – Great piece here, really helps put the current state of SME law in perspective.

It has become quite difficult to counsel execs with R&D budgets to spend in cutting edge areas such as AI, Distributed Ledgers, Context and Data Analytics, and Machine Vision whether any of the advances created will be protectable and enforceable down the road.

But patent terms are long, and the pendulum is continuously swinging. Recent legislative proposals and public positions set forth by the new director give me some hope of clarification and strengthening in this area.

Keep up the good fight.

Night Writer

May 8, 2018 09:04 pmJCD: >> Is the abstract ideas eligibility exception applicable outside of the context of an idea which is “a fundamental [] practice [that was] long prevalent”? This is still an unsettled question, and it is not clear that anyone other than the Supreme Court or Congress can provide a definitive answer.

This would probably be the easiest way for the CAFC to cabin in Alice. But you have to remember that about half the judges are Google judges and want to burn the patent system down.

Anon

May 8, 2018 05:40 pmAlas, Mr. Cole, we must part ways if you really feel that ANY Supreme Court jurisprudence since, well, since Chakrabarty has been “limited and careful.”

It just ain’t so – no matter what thesis you may want to hold onto.

Also, my more developed posts that touch upon Congress acting includes a reset of the Article III reviewing court, seeing as the current CAFC has been browbeaten into submission by the Supreme Court (yes, there is more blame for that Higher Court). I have pointed out that it is no longer enough to merely strip jurisdiction. Perhaps if Judge Rich were still around….

Paul Cole

May 8, 2018 05:26 pm@ Anon

My thesis, for several years, has been that it is the CAFC that needs to act – making correct interpretations of the recent Supreme Court cases and not over-interpreting what were explicitly limited and careful decisions.

And if Congress acts, you will merely shift the emphasis to the four eligible categories without making a substantial difference unless CAFC attitudes change.

Anon

May 8, 2018 03:31 pmMr. Cole,

I fear that you fall prey to the supposition that the US version of Useful Arts is merely some “Technical Arts” thing, as often those outside of the US do.

“Technical problem” then – per se – fails to match our Sovereign’s choice for patent eligibility (granted, this is taking the law as written by Congress as opposed to the one written by the Supreme Court as the guiding principle).

Also, may I remind you that “invention” is expressly NOT what our Congress opted for in 1952. That you seem to want to re-insert it (even as you want to place it in 103) is simply pure legal error.

The reason why Congress opted for something else was because Congress had provided authority to the judicial branch to arrive at that “hard definition” through the use of the tool of common law evolution, and the Court (specifically) had refused to do so, opting instead to play the “nose of wax” game, and especially after the very anti-patent era of the 1930s and 1940s (with the self-described phrase of “the only valid patent is one that has not yet appeared before us”) – arrived at a very similar historical point that we find ourselves at today.

Once before, Congress acted.

Once again, Congress needs to act – this time, with jurisdiction stripping of the TOP judicial entity that cannot rid itself of its wax addiction.

Paul Cole

May 8, 2018 02:30 pmOne of the great and enduring problems both in UK and in US patent law is that there is no legal definition of the general nature of an invention. No such definition has been built into 35 USC 103, and no such definition is prescribed by sections 1 and 3 of the UK Act or any rules made thereunder.

In contrast, PCT Regulation 5.1(a)(iii) provides that the description shall disclose the invention, as claimed, in such terms that the technical problem (even if not expressly stated as such) and its solution can be understood, and the advantageous effects, if any, of the invention should be stated with reference to the background art. The EPC implementing regulations contain the same language, but very unfortunately those who wrote the rules for the UK Act expressly decided not to adopt that language.

As explained to me at a CIPA meeting by the late George Szabo, the EPO Appeal Boards as a result of about a year of intensive study after the EPO started work but before appeal cases started to come through settled on technical problem as the best touchstone for inventive step. They announced in the first ever published Appeal Board decision that this would be the case, and have adhered to that ever since, technical problem being a reconstruction from the new function or result achieved vis a vis the closest prior art.

Unfortunately, UK and US statute, rules and case law leaves practitioners and judges floundering. Neither the Graham test in the US nor the Windsurfing test in the UK do more than requiring a preliminary investigation but abdicate responsibility or advice at the final stage or “make your mind up time.”

How are UK or US examiners or judges expected to identify invention under in the us ss. 101 or 103 if they have no clear and judicially supported explanation of what they are looking for?

Matters would be greatly improved if we could persuade the judges to close the gap and come to a universally acceptable definition. The wisest statement that I know of in the whole of patent law comes from Mr Justice Bradley in Loom Company v Higgins, 105 U.S. 580 (1881): “It may be laid down as a general rule, though perhaps not an invariable one, that if a new combination and arrangement of known elements produce a new and beneficial result, never attained before, it is EVIDENCE of invention.” That is what we as practitioners should be looking for, and if we fail to find it and describe it in the specifications that we write, them absence of evidence becomes persuasive evidence of absence.

It then becomes a matter of persuading the judges that new function or result within a technical field as opposed e.g. to business administration is equally persuasive under 101 as it should be under 103.

JCD

May 8, 2018 01:12 pmKudos on a great way of highlighting uncertainty engendered by the Court’s recent eligibility jurisprudence. The Court’s choice in Alice to decline to “labor to delimit the precise contours of the ‘abstract ideas’ category in this case” (Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S.Ct. 2347, 2357 (2014)) may have been reasonable, but it has left the problem that no one is really sure what should or should not qualify as an abstract idea for purposes of the eligibility exception.

The unsettled nature of this question is especially problematic given that the Court has made clear that “[i]n every case the idea conceived is the invention” (Gill v. United States, 160 U.S. 426, 434 (1896)), which makes it very easy to characterize almost any invention in some technology areas as an “abstract idea”. It seems very clear that the exception is not intended to apply carte blanche to any invention which could ever possibly be characterized as “abstract”, but this does not really do much to delimit the contours of the exception.

For example, in both Alice and Bilski, the Court made clear it was dealing with a fundamental practice that was long prevalent. See Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S.Ct. 2347, 2355 (2014) (“[l]ike the risk hedging in Bilski, the concept of intermediated settlement is ‘a fundamental economic practice long prevalent in our system of commerce.’”); Bilski v. Kappos, 130 S.Ct. 3218, 3231 (2010) (“Hedging is a fundamental economic practice long prevalent in our system of commerce and taught in any introductory finance class.”)

Is the abstract ideas eligibility exception applicable outside of the context of an idea which is “a fundamental [] practice [that was] long prevalent”? This is still an unsettled question, and it is not clear that anyone other than the Supreme Court or Congress can provide a definitive answer.

Anon

May 8, 2018 01:12 pmBen is as Ben does…

(this is nothing new from Ben)

Gene Quinn

May 8, 2018 12:30 pmBen-

Obviously, you missed the entire point of the article, and you are unfamiliar with the law of patent eligibility. Your comment reflects badly on you.

Ben

May 8, 2018 12:24 pmThe Chief Patent Counsel of IBM not being sure whether claim 1 of 3,744,036A is eligible reflects rather badly on IBM.

Anon

May 8, 2018 12:18 pmMr. Cole – upon reflection, we may indeed be making much the same point in different ways.

Paul Cole

May 8, 2018 12:13 pm@ Anon 6

I suspect that we are making much the same point in different ways.

It is considered under question 3 in my amicus brief to the US Supreme Court in Recognicorp v Nintendo (cert. denied) https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/17/17-645/22427/20171204145518298_17-645.amicus.final.pdf citing John Selden’s jibe published in 1689 that “equity varied with the length of the Chancellor’s foot” together with Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2016) and McRO, Inc. v Bandai Namco Games Am Inc., 837 F.3d 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

A definition of abstract would itself be ineligible on the ground that it is an abstraction. 🙂

Anon

May 8, 2018 10:27 amMr. Cole @ 3, with all due respect to the coiners of “over-reductionism,” verbiage already exists – and is already familiar to practitioners – that carry the same meaning (and I dare say, more colorfully so):

The Supreme Court’s provided weapon of the double edged sword of “Gist/Abstract.”

The “over” in over-reduction is merely the “Gisting” step which takes the invention as defined by the inventor (the proper entity that has been allocated by law with the authority to define the invention, per 35 USC 112), and reshapes (like a nose of wax) the invention to be what the Justices want it to be (and to move to another facial feature/analogy: the grin of the Chesire Cat as the Cat watches Alice converse with Mr. Dumpty).

The “abstract” part – well, we don’t have to bother defining that, now do we? 😉

Anon

May 8, 2018 10:21 amMr. Cole @ 2 – while you say weak, shall I venture a “I told you so” as to how courts may implement that very same “weakness?”

Anon

May 8, 2018 10:19 am“but if we cannot determine with reasonable certainty how all of these inventions would fare if judged under recent Supreme Court case law, then no one can truly teach Patent Subject Matter Eligibility 101.”

I daresay that this extends beyond mere teaching, and attaches to the very law itself.

Let’s be frank and call the state of law of 35 USC 101 to be a (Supreme Court) Justice-(re)written law.

And even if you want to maintain that the law is not re-written, and only “interpreted” anew, then we STILL have a law as written that cannot be known a priori how a judge (or Justice) is going to apply that law.

There is a concept that fobids US laws that exhibit this condition. That concept is called Void for Vagueness.

Granted, most often this concept is applied to criminal laws. But as I have shown certain Massachussets-barred attorneys, the concept is applied to civil law as well.

And especially civil law that has to do with property.

One of the (other) fallouts from the Oil States case is the attempt (with all due respect to Greg DeLassus**) of not making patents property; with the concomitant weakening of other protections under the Constitution FOR property.

Be all that as it may, the larger “elephant” here is whether any such current law (as “written” or “re-written” as it may be), holds up to scrutiny under a Void for Vagueness evaluation.

Let’s face it – if you cannot teach it, then what exactly does the law mean a priori (as opposed to how any later judge or justice may wish to shape such a wax nose).

**Whether or not a Franchise Right type of property carries the same level of other Constitutional protections is a discussion not yet had.

Paul Cole

May 8, 2018 10:11 am@ Night Rider

Many thanks for your comment and for the link to the madisonplace case.

“Over-reductionism” encapsulates concepts that I have been endeavouring to grasp in earlier postings today and are words that should now enter the vocabulary of us all because they say so much and so economically. Congratulations to Judges Hughes and Linn.

Paul Cole

May 8, 2018 10:04 amAdleman US 6671821 relates to “a public key system for establishing private communications and also for providing private communications with the signature. A characteristic of this system is that the public revelation of the encryption key does not reveal the corresponding decryption key. As a result, couriers or other secure means are not required to transmit keys, since a message can be enciphered using an encryption key publicly revealed by the intended recipient. Only the intended recipient can decipher the message since only he knows the corresponding decryption key. Furthermore, the message can be “signed” by deciphering it with the privately held decryption key.” The claimed system therefore has technical advantages relating to the operation of the system itself and not to the content of the messages contained in it. A non-eligibility attack would therefore, even under the current state of the law, be weak.

Liskov US 7166791 is similarly providing communication methods with improved fault tolerance which is plainly a technical attribute relating to the functioning of the system and falling within the eligibility realm.

Jobs 7166791 claims a method involving a multimedia asset player having a front surface that includes a display and a rotational input device, which are physical element relating to the “machine” or “manufacture” categories and overall the process is transformative.

The invention of US 3,744,036 very plainly falls within the eligible categories of “manufacture” and “machine”. Claim 1 of US 870302 though reading onto a physical structure is very broad and at first sight does not read clearly onto a field programmable gate array.

The Wynne invention US 4784135 concerns a method of treatment of the human body which has long been considered an eligible category, and the claimed method has a number of distinctive technical features. Again the eligibility attack would be weak.

None of this is to diminish the problem of legal and technical ignorance amongst many judges, and the uncertainty that their often superficial analysis and inattention to detail creates.

Night Writer

May 8, 2018 09:42 amhttp://www.717madisonplace.com/?p=9768

Total gibberish. Worse than a witch trial.

“which was improved by a natural law”, “in of itself”, “abstract idea,” etc.

“Abstract idea” is being used as “the invention” in a derogatory manner.

Can ANYONE tell me any evidence —ANY—that something being old and well-known related to the term “abstract idea” (in any sense of the word) prior to Alice? Anyone?