The political theories of John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Montesquieu and others greatly influenced our Founders in the creation of our nation, as well as our patent system. In particular, Locke’s political philosophy included the maxim that a person’s property or fruit of their labors should be protected by their government. James Madison, the father of the Constitution, and others inculcated this viewpoint of a patent system into the fabric of our nascent nation. Indeed, the only “Right” mentioned within the text of the Constitution is the right to secure protections under patent and copyright. The other Rights, i.e., Freedom of Religion, Security in One’s Home from Unreasonable Searches and Seizures, etc., are set forth in the attached Bill of Rights.

Despite the clear language of the Constitution, the Federalist Papers and other writings that the Lockean “natural rights” view governs, some academics try to decry this approach, and turn to other philosophies, such as John Stuart Mills’ Utilitarianism, to either bolster or undermine the usefulness of a patent system, usually undermine. Born thirty years after the creation of the United States (and nearly twenty years after the Constitution), Mill wrote extensively on individual liberty, freedom, logic and other issues, and is chiefly known for his principle of utilitarianism, the greatest good for the greatest number. His maxims are many, including “Originality is the one thing that unoriginal minds cannot feel the use of.”

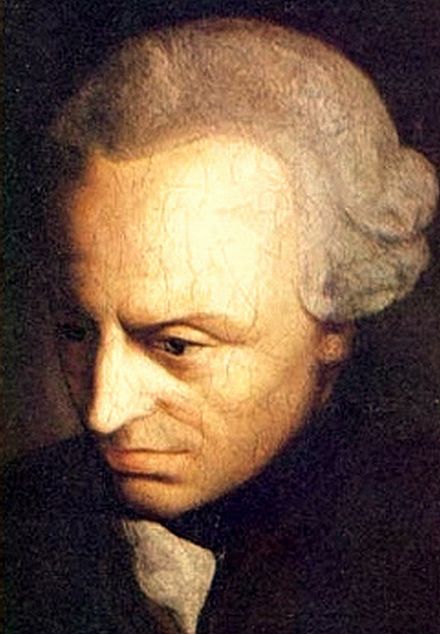

But there was another philosopher, contemporaneous with the Founders, that bears notice, Immanuel Kant, who had a different take on moral and political philosophy, including the Categorical Imperative. Kant spent his life trying to distill the issues of morality into a logical framework. Just as the natural scientists of the Enlightenment were forming logical arguments concerning the physical world, e.g., physics, natural science and other disciplines, Kant tried to do the same with human morality: systematize it.

In his Categorical Imperative, Kant simplifies a moral argument position for an individual by asking a question: if you thought that your position or Statement would be Universal, i.e., applicable to all people, it would have the stance of a Categorical Imperative and thus you must do it. For example, a Statement that I should try to save a person that is drowning can be considered a Categorical Imperative since this would be a betterment of humanity.

However, the proposition or Statement that it should be ok for me to steal another’s car is not a betterment at all. Applying this as a universal law would lead to societal chaos and possible collapse since thievery would reign, and anarchy would result. Since the entire purpose of government is the protection of people (and their possessions), this Statement fails, and you are NOT compelled to act in that manner. This Statement does not rise to the level of a categorical Imperative.

Intellectual property has been attacked of late on various grounds, including being less than property, and thus not entitled to the protections of the Constitution, despite the evidence to the contrary. This attitude is most recently, and most troublingly, exemplified by the U.S. Supreme Court in Oil States, where the Court equated patent rights to taxicab medallion rights. Freeriding is also being touted, subverting copyright law. Information must be free is the mantra.

As we shall see, applying Kantian logic entails first acknowledging some basic principles; that the people have a right to express themselves, that that expression (the fruits of their labor) has value and is theirs (unless consent is given otherwise), and that government is obligated to protect people and their property. Thus, an inventor or creator has a right in their own creation, which cannot be taken from them without their consent.

So, employing this canon, a proposed Categorical Imperative (CI) is the following Statement: creators should be protected against the unlawful taking of their creation by others. Applying this Statement to everyone, i.e., does the Statement hold water if everyone does this, leads to a yes determination. Whether a child, a book or a prototype, creations of all sorts should be protected, and this CI stands. This result also dovetails with the purpose of government: to protect the people and their possessions by providing laws to that effect, whether for the protection of tangible or intangible things.

However, a contrary proposal can be postulated: everyone should be able to use the creations of another without charge. Can this Statement rise to the level of a CI? This proposal, upon analysis would also lead to chaos. Hollywood, for example, unable to protect their films, television shows or any content, would either be out of business or have robust encryption and other trade secret protections, which would seriously undermine content distribution and consumer enjoyment. Likewise, inventors, unable to license or sell their innovations or make any money to cover R&D, would not bother to invent or also resort to strong trade secret. Why even create? This approach thus undermines and greatly hinders the distribution of ideas in a free society, which is contrary to the paradigm of the U.S. patent and copyright systems, which promotes dissemination. By allowing freeriding, innovation and creativity would be thwarted (or at least not encouraged) and trade secret protection would become the mainstay for society with the heightened distrust.

Also, allowing the free taking of ideas, content and valuable data, i.e., the fruits of individual intellectual endeavor, would disrupt capitalism in a radical way. The resulting more secretive approach in support of the above free-riding Statement would be akin to a Communist environment where the State owned everything and the citizen owned nothing, i.e., the people “consented” to this.

It is, accordingly, manifestly clear that no reasonable and supportable Categorical Imperative can be made for the unwarranted theft of property, whether tangible or intangible, apart from legitimate exigencies.

On the positive front, there is a Categorical Imperative that creators should be encouraged to create, which is imminently reasonable and supportable. Likewise, the statement set forth in the Constitution that Congress should pass laws “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” is supportive, as a Categorical Imperative, for the many reasons elucidated two centuries ago by Madison and others, and endorsed by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and later by Abraham Lincoln. A Categorical Imperative, universality, however, may be a stretch outside of the United States since other cultures may not treasure the progress of science and the useful arts and freedoms that we Americans do. Nonetheless, it is certainly a supportable proposition in the United States, and even a Categorical Imperative that we must do it!

Turning to issues facing us today, despite the categorical imperative nature of an intellectual property system, some powerful naysayers object to intellectual property per se, but on more fundamental grounds, pecuniary. A large amount of the condemnation of the intellectual property laws over the last decades has been from the big tech companies that would like to use new innovations for their own profit at the expense of the individual inventor. Ignoring the small entrepreneur or inventor is even de rigueur, i.e., most tech companies now have a “sue me” approach to patent infringement, which means openly taking patented technology knowing that a patentee is not likely to have the means to bring a costly litigation. To further undermine small inventors, the big tech companies, at the behest of Congress, instigated onerous administrative proceedings at the Patent Office, where the odds were stacked against patentees, proceedings often called “death squads” due to the very high percentage of patent invalidations.

Indeed, these patent-hostile, monopolistic companies lavishly fund lobbyists to further influence Congress on their behalf to diminish patents, thereby undermining the patent system and the value of patents, and increasing their profit margins with the freeriding. With all of the denunciation of the Chinese for freeloading our IP, we should perhaps look within first to make America great again. To add insult to grave injury these same companies have also supported numerous Supreme Court challenges to further undermine the patent and copyright systems. The recent appointment of Andrei Iancu as the new Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the United States Patent and Trdemark Office is a harbinger of a possible turning point toward a more positive patent system.

As a result of all of the big tech efforts to destabilize the patent system, the engine of innovation has suffered. To further harm the patent system, the press labels all inventors de facto trolls and thus unworthy. This demonization of inventors by the press has been profound. Gone are the days of an inventor being celebrated for building a better mouse trap or developing a nifty app. Now, even the Wright Brothers and Edison have been brought low, equated to trolls and not respected American innovators.

Immanuel Kant’s dream of systematizing morality is, of course, imprecise, but the meaning is quite clear and analogous to another famous maxim: do unto others as they would do unto you. Kant’s Categorical Imperative and the Bible extort us to be better people and form a better society. If, however, you feel that innovation is trivial and content should be free, then a Categorical Imperative for freeriding may be sane for you, but it fails at the societal level, i.e., universal application would undercut society. It is also wrong to steal. In the balance, society wants new ideas, new stories, new ways of doing things, and newness itself. All of this takes effort and expense, along with ingenuity and creativity, which should be strongly encouraged and not punished.

A Kantian Categorical Imperative to encourage, support and defend the creations protected by intellectual property is manifest. We should not be swayed by the arguments of corporate monoliths desirous of their own wellbeing and not society’s. In connection with his categorical imperative, Kant also believed that we should all “always recognize that human individuals are ends, and do not use them as a means to your end.” In other words, we should value and respect each human being and their contribution to the world. By deliberately or wantonly stealing patented technology from individual inventors, big tech companies treat them as a means to the corporate end, diminishing and dehumanizing the inventor.

Our Founders well knew that human beings create, and that the stuff of that creation has value. The patent and copyright clause, embodied within the Constitution itself, recognizes this need to encourage, facilitate and support the creativity embodied in us all.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-banner-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-938x313-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

8 comments so far.

Poesito

July 19, 2018 07:45 pmBenny is another kind of troll.

Anon

July 18, 2018 06:05 pmRay,

You tackle an immensely “thick” topic (philosophical tomes of the nature of patents): to certain things, “stuffy” is merely an appearance to those who do not understand the complexity of the topic.

Benny has shown that he does not appreciate the basics of patent law. His views on this aspect then carry zero weight.

In a time when our highest Court cannot seem to understand the nature of patents (vis a vis Oil States), “stuffy” is perhaps something that MORE OF is needed.

Raymond Van Dyke

July 18, 2018 03:49 pmThanks Night Writer and Anon for your defense of my literary style;) Nonetheless, perhaps I am a bit stuffy, but humorless is going too far on limited data. As for doing better, we can all always do better. As Blaise Pascal would have said here, “if I had more time, I would have written a shorter article.”

Anon

July 18, 2018 10:31 amBenny plays his usual role of the fool. He is simply not one to judge anyone on “literary standards.”

Night Writer

July 18, 2018 09:37 am@3 Benny

Or Benny doesn’t like the content —and cannot attack the content–so he went after the style.

Benny

July 18, 2018 05:32 amNot up to the usual literary standards of this blog, in terms of style (not content). Raymond comes across as stuffy and humorless. You can tell he has the ability to do better.

Anon

July 17, 2018 03:37 pmA fascinating topic.

Reminds me of a conversation** I had attempted with the late Ned Heller (who attempted to use the term “Categorical Imperative” from Kant incorrectly).

** As I recall, the conversation had to do with the nature of government providing protection for one’s inalienable (and natural) rights. Granted, personal property (pre-Oil States patents) are note PURE natural rights (think of the difference as the difference between an inchoate right and a mature right under the law), but certainly, patent rights are NOT as the post-Oil States view currently attempts to portray them – and our discussion touched upon the proper role of government in relation to the rights. Mr. Heller was much more of a “Might makes Right” viewpoint, and had attempted to co-opt the Kantian “Categorical Imperative” notion to support his view that the government is the creator of the right because of its power to enforce – whereas a more Lockian and natural rights view is that the right exists whether or not the government enforces (and it is a separate issue as to WHETHER the government enforces).

Mark Martens (@MarkMartens42)

July 17, 2018 11:56 amAnd I think that’s nicely done Raymond Van Dyke.