“Patentability statutes do not, and cannot, address actual products—it is the claim that must be enabled by the patent specification; and the invention as claimed must meet the utility requirement.”

Last week, the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet, held an oversight hearing on the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) with Director Andrei Iancu as the sole witness. A particular inquiry from Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) regarding the USPTO’s allegedly lax examination quality under 35 U.S.C. § 112 caught my attention. She remarked [at 1:33:30]: “Theranos, the blood testing company whose founder is being investigated for fraud, was granted nearly 100 patents based on an invention that didn’t work; and it concerns me that a patent application for an invention that doesn’t work gets approved.” She generally questioned examiners’ attention to Section 112 requirements. Rep. Lofgren’s statement was no doubt primed by information from the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) in the Ars Technica blog post titled “Theranos: How a broken patent system sustained its decade-long deception.” In this article, the author, who was introduced as holding the “Mark Cuban Chair to Eliminate Stupid Patents” at EFF, declares with no evidence or proof, that the “USPTO generally does a terrible job of ensuring that applications meet the utility and enablement standards.” The article cited no study, identified no patent, nor any claim to any “invention that didn’t work.” This outrageous, baseless allegation is outright reckless and irresponsible.

- A Decade-Old Assault

We have seen this movie before. Anti-patent narratives are disseminated through media and congressional committees in a campaign to impugn the examination quality of the USPTO with anecdotal innuendos, mythical premises, distorted logic, and flawed evidence. This latest EFF allegation continues the decade-old, systematic, unjustified assault on the reputation of the USPTO’s examination process by using bad science in search of “bad patents.” This assault is continued today to ridicule USPTO allowances, to undermine patents’ presumption of validity, and to pressure the USPTO to return to the mid-2000s culture of “reject, reject, and reject.” The article on Theranos alleging a “broken patent system” proved nothing of the kind. Contrary to the premise of the article, the statutory utility and enablement standards are neither designed to avoid issuing “stupid patents” (which harm no one), nor can they ensure that actual products work. And these statutes certainly do not empower or authorize the USPTO to substitute its judgment for the Security and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) in policing or eliminating fraud on investors. Furthermore, the notion that “100 patents” were issued “based on an invention that didn’t work” is fictional because many of those issued Theranos patents cover subject matter that is peripheral, secondary, and unrelated to the alleged “invention that didn’t work.”

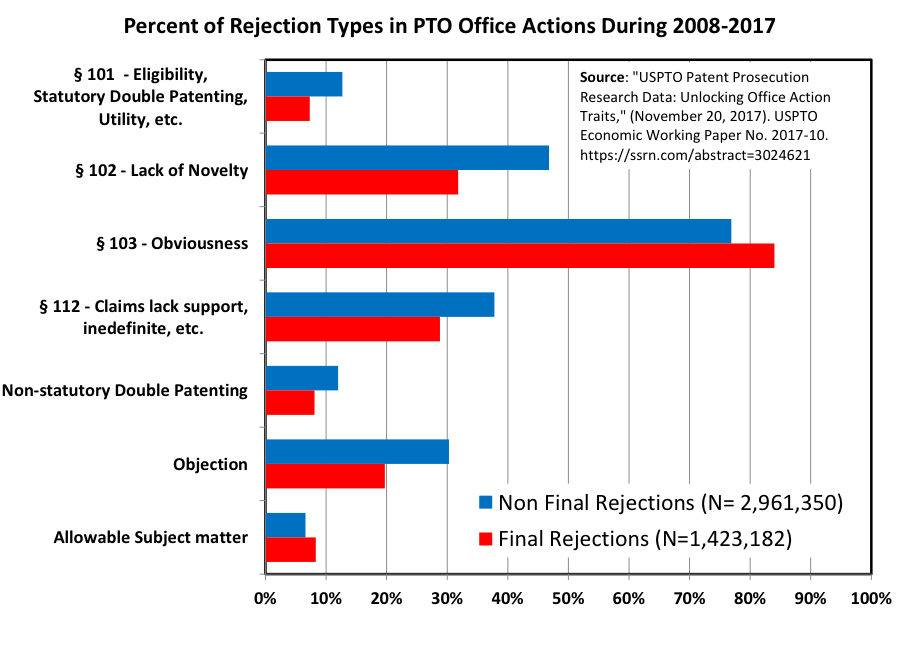

To be sure, as Director Iancu himself acknowledged, examination procedures can and should be improved. But that does not mean that EFF’s allegations have merit. That examiners seriously attend to Section 112 requirements is evident from the relatively high percentage of such rejections in USPTO office actions, particularly in initial rejections (see accompanying figure). More specifically, other empirical evidence suggests that the USPTO’s allowance error rate on claim enablement is the lowest among its other major allowance error categories. Data on patent litigation published by the Institute for Intellectual Property & Information Law (IPIL) at the University of Houston Law Center, shows that patent challenges for lack of enablement were the least successful in federal courts among challenges under major statutory patentability criteria. For example, patentees were 62% more likely to prevail on Section 112 enablement than they were on anticipation over published prior art under Section 102(b). In any event, the basic predicates underlying the EFF allegation and Rep. Lofgren’s remarks are flawed, as explained below.

- Mischaracterization of the invention “working” requirements

First, patentability statutes do not, and cannot, address actual products—it is the claim that must be enabled by the patent specification; and the invention as claimed must meet the utility requirement. Thus, the examiner’s focus must be on the claim, ensuring that each limitation and interconnections of the claim is enabled by the specification, as the statute in Section 112 requires. The USPTO does not examine claims made in press releases. Enablement of a patent claim cannot guarantee that any product feature that the applicant promises in a press release to deliver to market would actually work. Second, an applicant need not have actually reduced the invention to practice prior to filing. Gould v. Quigg, 822 F.2d 1074, 1078 (Fed. Cir. 1987)(“The mere fact that something has not previously been done clearly is not, in itself, a sufficient basis for rejecting all applications purporting to disclose how to do it.”) Indeed, we will have a lot less disclosure and investments in new inventions if one were to erect “working” requirement barriers for applicants. This is particularly true now that the first-to-file provisions in the America Invents Act (AIA) shift the risks onto those who take more time to experiment and vet their invention prior to filing; and completing this “Catch-22” jeopardy, the countervailing risk of not verifying the “working” of the invention is also borne by the applicant.

Constructive reduction to practice is recognized no later than the date the patent specification compliant with Section 112 is filed. Hyatt v. Boone, 146 F.3d 1348, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 1998). However, the scope of the claims is limited to that which is enabled in the specification, AK Steel Corp. v. Sollac, 344 F.3d 1234, 1244 (Fed. Cir. 2003); and thus there is little harm to the public if an inventor gains exclusive right to an invention that does not work, or is “stupid.” If anything, the disclosure is beneficial as it can teach others how to overcome its faults and invent an improvement that actually does work.

Similarly, the public suffers little harm if the examiner, despite correctly verifying that all claim limitations are properly enabled by the specification, cannot mentally construct an actual product to recognize that the invention as claimed may not work. This recognition is required in order to reject for lack of utility. While examiners do reject claims if specific utility is not disclosed in the specification, the IPIL data shows that failure to meet the utility requirement was never challenged in patent infringement suits. This is likely because any alleged infringer who would argue that the claims cover an invention lacking utility supplies his own proof to the contrary by his infringement—the infringer is usefully “utilizing” the claimed invention. In other words, there could be no risk of actual infringement of a claimed invention that does not work. This counterfactual is a bit like Woody Allen’s complaint that the food in summer camp was “terrible” and that the “portions they served were too small.”

Until the Patent Act of 1870, applicants were generally required to submit a “model” of the patented invention to the USPTO, to help examiners and the public (who upon request could gain access to the model room) learn how the claimed invention operates. But Congress recognized that the costs imposed on applicants for making models and paying fees for the Office to house and preserve them was often prohibitive for ordinary citizens and had a chilling effect on incentives to disclose new inventions. Congress also recognized that, with the advent of the electrical and chemical arts, many inventions do not admit to the use of “models,” and thus repealed the model requirement and relied on the language in what is now Sections 112 and 113, the latter requiring that “[t]he applicant shall furnish a drawing where necessary for the understanding of the subject matter sought to be patented.” The USPTO regulations in place since before the 1952 Patent Act go even further than the statute, requiring in 37 C.F.R. § 1.83(a) that the “drawing … must show every feature of the invention specified in the claims.” Examiners often require compliance with this rule, as those who frequently receive “objections to the drawings” in office actions can attest.

The test for determining whether the specification meets the enablement requirement was judicially set a century ago by the Supreme Court in Minerals Separation Ltd. v. Hyde, 242 U.S. 261, 270 (1916), which created the question of whether the experimentation needed to practice the invention is undue or unreasonable. This standard is still the one applied by the Federal Circuit today. Trustees of Boston University v. Everlight Electronics Co., Ltd., 896 F.3d 1357, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (“[T]o be enabling, the specification of a patent must teach those skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation.”) (My emphasis). The test of enablement is not whether any experimentation is necessary, but rather “the issue is whether the amount of experimentation required is ‘undue.’” In re Vaeck, 947 F.2d 488, 495 (Fed. Cir. 1991). Technically, the information in the claim and the specification should permit the examiner to determine which claimed elements are adequately enabled and which require a degree of experimentation. However, the examiner may not be able to show that the experimentation would be unsuccessful—a showing that must be made as part of the examiner’s initial burden to establish a reasonable basis to question the enablement provided for the claimed invention. In re Wright, 999 F.2d 1557, 1562 (Fed. Cir. 1993). Many meritorious and useful inventions would lose patent protection if examiners would be permitted to speculate inoperability and reject a claim with no proof by shifting the burden onto the applicant, contrary to the requirement of MPEP § 2164.04.

- The self-regulating features of U.S. patent law improve compliance

Ultimately, the legal system and the nature of patent enforcement provided self-regulating forces for applicants’ compliance with enablement requirements that supplemented the USPTO examination process, by independently creating strong incentives and public protections as follows:

- As discussed above, a patent holder is not entitled to a claim interpretation that is not enabled by the specification. Applicants have incentives to provide such claim support in the first place. Unfortunately, the AIA’s first-to-file provisions necessitate races to file first, sometimes with half-baked inventions, undermining the quality of patent disclosures.

- A patent need not teach, and preferably omits, what is well known in the art. In re Buchner, 929 F.2d 660, 661 (Fed. Cir. 1991). However, applicants often err on the side of further disclosure because arguing otherwise—that an element in the claim is enabled as being well-known in the art—essentially constitutes an admission that an examiner’s rejection of that claim for anticipation and/or obviousness may be justified.

- The “utility” prong is essentially self-executing because an applicant would seldom spend resources to protect that which has no utility.

- The “Best mode” requirement coupled with the “grace period” was also self-enforcing: “The specification. . . shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention.” 35 U.S.C. § 112(¶2) (pre-AIA). Applicants were highly incentivized to disclose the best way to implement the invention in the first place because a discovery and allegation that applicant concealed from the USPTO the best mode known to the inventor at the time of filing is an affirmative defense of inequitable conduct, which could render the patent unenforceable. This is a significant and nontrivial matter: owing to the doctrine of equivalents, applicants may obtain strong claims based on disclosure of suboptimal embodiments that conceal the inventors’ competitive advantages. The grace period permitting the inventor more time to perfect the invention and disclose the best mode on the one hand, and the requirement for such best mode disclosure on the other hand, can be seen as the American second patent bargain—one-year grace period for optimizing, reducing to practice, and perfecting inventions in exchange for the inventor’s disclosure of the results of this optimization—the best mode for practicing the invention. Unfortunately, the AIA did away with this second patent bargain by eliminating the best mode defense, 35 USC § 282(b)(3)(A), and the Supreme Court decision in Helsinn v. Teva confirmed that it also eliminated the “on-sale”/“public use” grace period, undermining the quality of patent disclosures.

The USPTO must examine claims for patentability under a limited time per application (about 26 hours on average); one cannot expect the Office to be the custodian and public trustee of “peer review” services on specific designs claimed in patent applications, rendering determinations on the technical feasibility of implementing the claimed inventions. While USPTO examination quality should be generally improved, there is no evidence of a trend suggesting that the USPTO “does a terrible job of ensuring that applications meet the utility and enablement standards.” In fact, there is empirical evidence to the contrary. Pinning unjustified blame on the USPTO is a familiar tactic of the “efficient infringement” cabal. If any blame for a declining quality of enabling disclosures should be placed, it is squarely on the enactment of the AIA, which repealed important self-regulating disclosure safeguards that were established over more than two centuries.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

20 comments so far.

Brian Coyle

August 9, 2019 05:28 pmNeither this article, nor EFF and Lofgren, are all right or all wrong. I have a real interest in the discussion, but I’m really troubled by the degree of black/white thinking evinced in the article and esp. comments. Is this how the internet has trained us to think? Or is it just bad habits … Politics responds to crisis, because the public demands it. Theranos is a crisis. Maybe most of those 100 patents were minor, but some weren’t. Just as supposedly educated investors were bamboozled, so were examiners. There’s no way someone with reasonable knowledge and capacity to self-inform shouldn’t have raised red flags about Theranos. Both investors and examiners made egregious mistakes that merit serious reflection.

Utility does matter. The USPTO doesn’t force medical products to run trials. That’s the FDA’s job. If trials were prior to patenting, they’d let the cat out of the bag. But courts made clear that doesn’t give medical products carte blanche. The USPTO should expect, and demand, scientific research and affidavits. It should have demanded Theranos to provide scientific articles demonstrating how their absurd sampling regime could work. Given the claims’ ramifications, the examiner should have committed 8 hours to searching bioscience journals with key words for potential constraints. Especially since medical devices don’t require FDA tests.

There are plenty of imaginary devices out there that no one has any idea of making. Just because they’re complex doesn’t relieve the USPTO of demanding science that shows how they’ll work.

The recent intro of “3rd party review” allows anonymous outsiders to flag patentability issues of applications. What’s needed is a way to channel these effectively. The USPTO emphasizes 3rd party review’s prior art purpose. But it can, and should, address enablement problems. 3rd party input could be a way well-heeled corp.’s use bad science against interlopers. Examiners need to be empowered to recognize good science that demonstrates enablement issues.

This article mocks the request for examiners to become peer reviewers. In fact, that’s not a bad idea. Examiners should be able to flag questionable tech, and have several other examiners give him/her feedback. I imagine this might occur informally. Why not make it formal?

PS: The article’s claim that “the “utility” prong is essentially self-executing because an applicant would seldom spend resources to protect that which has no utility” is incorrect. University staff and company employees get promoted in part due to patents. Also, patents are filed as place holders. If they’re granted, the institution might try to figure out enablement. It might fail, when others would succeed. It might not bother, because the effort is crowded out. Of course, patent trolls also exist.

Ron Katznelson

May 18, 2019 05:59 pmGG,

Sorry if my frustration came too strong in my comment, but it is equally “not pleasant interacting with you” when you exhibit manifest dismissive disdain by accusing me – not the EFF author – for “zero analysis of what happened in those cases in terms of 112 issues” and for failing “in the public purposes” of explaining those cases. You keep doubling down on this burden-shifting bias again @ 18: “maybe a discussion of the specific material issues related to Theranos would have been useful.” Maybe. But who has the burden of doing so to prove their point? — the EFF author. The legal requirement to prove his proposition is on a claim-by-claim analysis, showing which specific claim limitation lacks adequate enablement support in the specification. This is the only way to prove the proposition advanced by the EFF author, a step he failed to take even for a single patent claim of any of Theranos’ 100 patents.

So yes, I only “analyzed the legal issues” because the EFF author made a legal argument. Please direct your desire for a “discussion of the specific material issues related to Theranos” to the EFF author who made the baseless allegation in the first place.

C.P.,

After all these exchanges, you still have the concept of burden of proof backwards. You say @15: “The premise [of Ron’s post] is that the lack of data proves there is no enablement issue.” You are wrong — there is no such premise. Rather, the premise is that of the EFF author that there is an “enablement issue.” That is the factual proposition here and my article shows that the EFF author failed to prove this fact even for a single patent claim. One cannot prove a negative — my statistical information alone cannot prove that there is “no enablement issues,” and I never claimed that one cannot find circumstances of such issues. The stats were provided only to suggest that the EFF author has a heavy burden of showing that “the USPTO generally” fails on such enablement issues.

Also, there are some 1/4 million of patents issued per year. if you want to raise a new topic of whether one finds enablement issues in IPRs — proceedings that self-select several hundred patents per year that may have been issued in error — then you are welcome to write another article on that. But this is not what the EFF author alleged; he alleged that the “USPTO generally does a terrible job” on enablement and utility standards. Your comments do not address or salvage the infirmity of this baseless allegation.

Gaurav Goel

May 18, 2019 02:09 pmRon, You analyzed the legal issues, but maybe a discussion of the specific material issues related to Theranos would have been useful. Also, I am not part of an anti-patent cabal. It’s really not pleasant interacting with you when you exhibit such belligerence and a complete unwillingness to even acknowledge what others are trying to tell you, which is not always in bad faith as you assume. Goodbye.

Anon

May 18, 2019 01:28 pmCP in DC,

Not to speak for Ron, but you have not captured the premises correctly.

You redirect the article with WANTING the premise to have a hole in it. It is YOUR restatement that introduces the strawman of a invalid argument and of being based on a logical fallacy.

The premise is NOT that the lack of data proves there is no enablement issue.

The premise is that A lack of data is being used as a conclusive FACT that ALL examination has an inherent problem of there BEING enablement issues.

The premise is NOT whether or not any individual item may or may not be (or may have been) properly evaluated for enablement.

What you see here is a purposeful manipulation of a genuine public concern as an attack on patents in a larger general sense.

THAT is the premise.

Ron rightfully points out that there is a difference in context for the LEGAL notion of enablement and the different NON-LEGAL “conversational” view that obfuscates just what a patent application is.

As I noted (here, elsewhere, and else-when), a patent is NOT an engineering document. It is simply legal error to confuse this point. It is dastardly to purposefully confuse this point. And it certainly does NOT help to confuse this point, and attempt to embed the confusion in any legal process – be that a legal process of Congressional Q & A, a legal process of the executive branch setting protocols, or a legal process of the judicial branch interpreting (under PROPER interpretive function) the law as written by Congress.

You carry an implied “threat” that the Supreme Court may “address” what THEY may deem to be a problem – and I have to wonder if YOU grasp just how much of a problem THIS type of action is. Whether or not “harmless” this type of implicit (and perhaps even unknowing) extension of authority for policy setting is an IMPROPER use of the judicial authority in view of how patent law was explicitly set in our Constitution to be the domain of a single branch of the government.

Jay shu

May 18, 2019 10:56 amGreat work for the independent inventor

CP in DC

May 18, 2019 09:22 amRon, the article is based on a logical fallacy. No distractions.

The premise is that the lack of data proves there is no enablement issue. The lack of data only proves there is a lack of data. The graph (which you keep using) or IPL study demonstrate that more 103 rejections were issued than 112 (all types). The graph also demonstrates that when you divide the 112 rejections into lack of description, lack of enablement and indefiniteness (all 112 rejections), examiners issue few enablement rejections (dividing the number equally among all three, because I have no data). This does not mean applications are enabled.

FOCUS. will do.

On April 29, 2019, in Grunentahl GMBH v Antecip Bioventures PGR2018-00001 PGR = post grant review) US patent 9539268 found all claims 3-30 (they disclaimed 1-2) NOT enabled. But let the details speak for themselves.

The claims were directed to a method of treating arthritis by administering zoledronic acid. As the PTAB put it, the claims are “broad, covering any oral zoledronic acid dosage form having the CLAIMED bioavailabilities.” (emphasis me). The exchange on page 14 is telling:

On that point, Dr. Wargin, Patent owner’s witness, agrees that the specification is silent.

Q. There is no actual data on any particular dosage form of zoledronic acid regarding bioavailability?

A. There is no actual data, that’s true.

Ex. 1093, 89:17-22 (deposition transcript).

Well the issued patent was filed on 2016 (after 2012), so it falls under PGR and this is post-Theranos. The application was examined post-Theranos and granted by an examiner. The application issued in the life sciences a highly unpredictable field with nothing to back up the claims.

This is a recent example that enablement is an issue in the highly unpredictable life sciences practice (that’s how we argue non-obviousness). This case is after the Theranos mess and it still issued. And it came at a cost to Grunenthal that had to pay to invalidate an issue patent (what around 400k?). Hardly, harmless.

I didn’t give credit to the messenger (now who needs to focus and read my post). I said don’t kill the message. The 112 issues are notorious problems in life sciences patents with the rampant over claiming. You may ignore my post, you may ignore the case, but if we as practitioners continue to ignore the problem and not address it, someone else (I’m looking at you Supreme Court or Congress) will address the problem for us, and we all know those results.

Ron Katznelson

May 17, 2019 06:10 pmCP, no distractions please – focus on the main point of my article. CP @ 12 “It’s not a ‘baseless allegation’ when examiners fail to examine for all requirements of patentabiity.” Where is the EVIDENCE that “examiners fail to examine for all requirements of patentabiity”? Conclusory statements are not evidence. Where is the EVIDENCE that “the USPTO generally does a terrible job” on enablement? Where, as here, there is no evidentiary basis for an alleged proposition, the allegation is by definition “baseless.”

Before one gives any credit to the “messenger,” one must demonstrate that there is a “message.” Please point to a single patent claim for which the EFF “messenger” demonstrated inadequate enablement or utility in the disclosure. I am not suggesting that one may not find such instance by looking at all 100 Theranos’ patents. What I am saying, however, is that the EFF article made no such specific showing – it makes baseless allegations.

See my comment @ 13 for further answer to your comment and as to who bears the burden of proof.

Ron Katznelson

May 17, 2019 03:14 pmGG @ 8: ”To the extent that this article was supposed to be a rebuttal of the Ars Technica piece on Theranos, there is zero analysis of what happened in those cases in terms of 112 issues. So, this article fails in the public purpose aspect of explaining the consequences of patent law, as it plays out in examination.”

This perverted logic is a common tactic of the anti-patent cabal:

EFF throws out baseless allegations to media outlets and their followers like GG @ 8 here accept these as true, rushing to shift the burden on others to disprove it. But GG has it all backwards: it is the EFF that provided zero evidence and “zero analysis of what happened in those cases in terms of 112 issues.” One cannot rebut a null set. The party alleging a factual proposition bears the burden of proof on that proposition. Only when that party comes forward with evidence in support of that proposition, can a rebuttal of the allegation be entertained.

The EFF author is the proponent of the proposition that the “USPTO generally does a terrible job of ensuring that applications meet the utility and enablement standards;” and he failed to move forward with any evidence in support of that proposition. GG’s perverted logic pointing in the wrong direction as to who “failed in the public purpose” is breathtaking.

CP in DC

May 17, 2019 02:50 pmRon @ 10

let me see how I misunderstood your article:

1st paragraph:

“She generally questioned examiners’ attention to Section 112 requirements.” Followed by an accusation.

2nd paragraph:

“Anti-patent narratives are disseminated through media and congressional committees in a campaign to impugn the examination quality of the USPTO with anecdotal innuendos, mythical premises, distorted logic, and flawed evidence.”

I provided case law that proved examination was flawed, and allowed patents were found invalid under 112.

3rd paragraph:

“That examiners seriously attend to Section 112 requirements is evident from the relatively high percentage of such rejections in USPTO office actions, particularly in initial rejections (see accompanying figure).”

These are your words, and they do not parcel out description, enablement, or best mode. You used the graph to make your point. I simply noted the biased source (the PTO not you) and questioned the accuracy of the graph in view of the recent case law presented.

You also wrote:

“However, the scope of the claims is limited to that which is enabled in the specification, AK Steel Corp. v. Sollac, 344 F.3d 1234, 1244 (Fed. Cir. 2003); and thus there is little harm to the public if an inventor gains exclusive right to an invention that does not work, or is “stupid.”

Well, it also has to be described another pesky requirement that is glossed over. And the public is damaged when they must spend resources finding out those pharma patents don’t work (over claiming is a problem). You can’t build a work around if you “think” the full scope of the patent is described and enabled, because it is an “issued” patent that was “examined.”

The Nuvo case addressed the interplay of description and enablement. But I went on the language of the article as quoted above. Enablement and description are matters of patentability examined by the USPTO.

As you state:

“This baseless allegation pinning false blame on the USPTO is the theme of the “movie we have seen before,” and the theater was not empty — you simply went to the wrong theater.”

It’s not a “baseless allegation” when examiners fail to examine for all requirements of patentabiity. And as to stupid patents, I have posted those for the swing set and stick (even this site has posted those), but my concern goes to those patents that do no enable (and describe) the full scope of the claim and yet get allowed. Your article addresses examination by examiners. Now who is responsible that?

All I warn is not to kill the message because of the messenger. Even Iancu agrees that examination can improve. If you want proof, compare a EPO issued patent and the corresponding US case. The differences are notable.

Gaurav Goel

May 17, 2019 02:31 pmRon, Dude, chill out, no need for such defensiveness. Your article is a good one. The only point I was making is that the article is written to an audience of patent practitioners, and that may well be appropriate here in this website. But that does not necessarily translate into meaningful information that the general public can appreciate and digest, especially in response to Ars Technica. Generally most folks eyes glaze over when discussing 112 issues, just saying, unless they see direct relevance to themselves.

Ron Katznelson

May 17, 2019 01:36 pmCP @ 7. It is apparently you, not “the author,” who “missed some important issues” — the subject of the article. The article is about the EFF allegations that the “USPTO generally does a terrible job of ensuring that applications meet the utility and enablement standards.” These allegations were devoid of any study or any fact showing that any specific patent claim was not enabled or lacked support for utility in the specification. This baseless allegation pinning false blame on the USPTO is the theme of the “movie we have seen before,” and the theater was not empty — you simply went to the wrong theater. Both cases you cite were about Written Description deficiencies — not about enablement. But he EFF article did not allege WD deficiencies. While the general statistics for Section 112 rejections in the graph subsume all types of 112 rejections (including WD rejections), my article addressed specific evidence from IPIL on enablement which you ignored. This article is NOT about WD issues, nor about section 112 generally. The author did not “miss important issues” – these issues are simply not covered being outside the subject of this article.

Benny

May 17, 2019 12:12 pmI can’t fault the examiners for not understanding that the Theranos patents are not enabled. But the idea that no harm is done by granting non-enabling patents… Well, harm was done in this case.

Gaurav Goel

May 17, 2019 11:12 amI think this article does bring up relevant points. However, all that is presented is the basics of patent law, and in a relatively abstract sense. To the extent that this article was supposed to be a rebuttal of the Ars Technica piece on Theranos, there is zero analysis of what happened in those cases in terms of 112 issues. So, this article fails in the public purpose aspect of explaining the consequences of patent law , as it plays out in examination.

CP in DC

May 17, 2019 09:14 amThe author has missed some important issues. 112, has several components description, enablement, and best mode and not just enablement. See Ariad.

You may have “seen this movie before” but recent case law says it was an empty theater. Nuvo v Dr. Reddy came out on May 15th. The Federal Circuit reverses the district court finding of description and enablement. If that was too recent, then look at Purdue v Iancu out on April 17. Description in provisional application (which must meet 112 in its entirety) found lacking in the priority document. I like the latter because of the common problem of laundry lists, see pages 10 and 11.

The cases address the “over claiming” problem and require demonstrating possession of the invention described in the claim. Not just saying it, the cases even quote In re Ruschig and that case is over 50 years old. Looking at PTO statistics is misleading, look at the recent case law. Examiners let a lot go by, and provide a declaration and they accept it regardless of scope.

Let’s not ignore the 112 problem, it’s real. If correctly applied, 112 may even help with 101…

I apologize if this got posted twice, something happened during drafting.

Anon

May 17, 2019 09:04 amPaul Georg,

I am not certain that I am understanding what you are trying to say.

On the one hand, examiners (not third parties) are required to make sure that the claimed invention has utility and meets the legal requirement of enablement.

This is black letter law (and I would dare say the point of Ron’s article).

There may be a separate rumination as to just why would a third party spend ANY effort in attacking a claimed invention that “does not work.”

If the claimed invention does not work, then NO third party would be pursing that avenue, and such a granted patent does no harm.

I realize that this way of stating the issue is perhaps a bit too glib.

It is not really a matter that the claimed invention does not work. Actually, the complaint (necessarily) resolves down to the claimed invention DOES work and is something that a third party wants to engage in, but without paying “tribute” to a patent holder of that “working” claimed item. (Granted – this IS different than the Lofgren Spin that Ron takes exception to).

This “different” avenue is pursued by the third parties who try to attack the specification for lack of enablement.

Putting aside the (deliberate) conflation of the likes of Lofgren, one SHOULD recognize that the “thinning” of specifications is a natural consequence of patent profanity induced by judicial members jacking up the power of PHOSITA as a manner of denying full strength to patent holders. I have explained previously that by making PHOSITA stronger, one provides that LESS is required to actually be captured in specifications (for enablement). That trailing edge of the double edged sword cannot be separated from the leading edge.

Additionally, as I have oft reminded people, patent specifications are LEGAL documents. They are not ENGINEERING documents. Some refuse to accept this fact and the necessary consequences of this fact.

Paul Georg

May 17, 2019 07:13 amFrom a European perspective, I can concurr to the fact that a rejection/invalidation based on the enablement requirement not being met is rare. But why would a third party attack a patent that claims non working matter? Is this really a good indicator? Especially in the “biological arts”, it seems difficult for an examiner to judge whether the enablement criteria are met because of the (still) prevailing unpredictability of the result of an interaction. It is thus for a competitor to challenge the claims and we should not be shy in admitting/stating this.

EG

May 17, 2019 07:07 amHey Ron,

Your article is spot on. As far as Zoe Lofgren, what else could you expect from a Congressperson “bought and paid for” by the SV multi-national tech Goliaths?

Peter Kramer

May 17, 2019 06:13 amit would seem to me that EFF is barking up the wrong tree. If they are concerned about inventions that lack utility, then 101 should be grounds for rejection. But under 101 even an invention that doesn’t work well doesn’t lack utility unless it doesn’t work **at all**.

Pro Say

May 16, 2019 05:25 pmExcellent article Ron — thanks.

When the facts are on your side, pound the facts.

When the law is on your side, pound the law.

When they’ve got neither, the EFF pounds the table, the media, legislators, and anyone else improvidently willing to lend them an ear.

Josh Malone

May 16, 2019 04:36 pmGood catch Ron. It is shocking that big tech lobbyists and their mouthpieces like EFF can critique the minutia of reams of data supporting reliable patents, such as articles here on IPW. Then on a whim they can instantly gin up legislation and testimony on a totally fabricated issue without any data whatsoever.