“The CAFC agreed with the district court finding that claim 12 of the ‘913 patent was nonobvious, and thus affirmed the district court’s finding that Actavis’s generic drug infringed the ‘913 patent.”

On October 9, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) issued a decision in HZNP Medicines LLC v. Actavis Laboratories UT, Inc. affirming the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey’s findings of invalidity and noninfringement of certain claims of some of the asserted HZNP (Horizon) patents, as well as the district court’s finding of nonobviousness of one claim of another Horizon patent. The finding of nonobviousness means that Actavis, owned by generic drug maker Teva Pharmaceuticals, is enjoined from engaging in the commercial use, offer for sale, or sale of its product covered in its Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) until the expiration of U.S. Patent No. 9,066,913 (the ‘913 patent) in 2027.

On October 9, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) issued a decision in HZNP Medicines LLC v. Actavis Laboratories UT, Inc. affirming the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey’s findings of invalidity and noninfringement of certain claims of some of the asserted HZNP (Horizon) patents, as well as the district court’s finding of nonobviousness of one claim of another Horizon patent. The finding of nonobviousness means that Actavis, owned by generic drug maker Teva Pharmaceuticals, is enjoined from engaging in the commercial use, offer for sale, or sale of its product covered in its Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) until the expiration of U.S. Patent No. 9,066,913 (the ‘913 patent) in 2027.

Horizon’s patent claims relate to methods and compositions for treating osteoarthritis, and include a number of U.S. patents, of which claim 10 of U.S. Patent No. 8,546,450 demonstrates the use of the asserted claims of the method-of-use group, of which all share a similar specification:

10. A method for applying topical agents to a knee of a patient with pain, said method comprising:

applying a first medication consisting of a topical diclofenac preparation to an area of the knee of said patient to treat osteoarthritis of the knee of said patient, wherein the topical diclofenac preparation comprises a therapeutically effective amount of a diclofenac salt and 40–50% w/w dimethyl sulfoxide;

waiting for the treated area to dry;

subsequently applying a sunscreen, or an insect repellant to said treated area after said treated area is dry, wherein said step of applying a first medication does not enhance the systemic absorption of the subsequently applied sunscreen, or insect repellant;

and wherein said subsequent application occurs during a course of treatment of said patient with said topical diclofenac preparation.

Claim 49 of U.S. Patent No. 8,252,838 demonstrates the use of the asserted claims of the formulation patent group:

49. A topical formulation consisting essentially of:

1–2% w/w diclofenac sodium; 40–50% w/w DMSO;

23–29% w/w ethanol; 10–12% w/w propylene glycol;

hydroxypropyl cellulose;

and water to make 100% w/w, wherein the topical formulation has a viscosity of 500–5000 centipoise.

Markman Hearings Find Formulation Patent Claims to Be Indefinite

Both groups are listed with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (Orange Book) for Horizon’s PENNSAID® 2% product. PENNSAID® 2% is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and the first FDA-approved twice-daily topical diclofenac sodium formulation for knee pain due to osteoarthritis. Prior art PENNSAID® 1.5% differs from PENNSAID® 2%, in formulation and recommended dosage through application of 40 drops to the knees four times a day. In contrast, PENNSAID® 2% reduces frequency of application to twice a day at a lower dosage of 40 mg.

Actavis pursued the marketing of a generic version of PENNSAID® 2% and filed an ANDA, including a certification that the patents-at-issue were either invalid or would not be infringed by the generic product. Following notice of the ANDA certification, Horizon filed suit against Actavis on December 23, 2014 for patent infringement. The Hatch-Waxman Act allows for the filing of a such patent infringement lawsuit after the filing of an ANDA even though there technically has yet to be any infringement. In essence, Hatch-Waxman defines the filing of an ANDA with a paragraph IV certification (i.e., that the patent is either invalid or not infringed) a technical act of infringement that provokes an actual federal controversy appropriate for adjudication in federal court.

In order to evaluate claim construction of the patents, Markman hearings took place in 2016, finding three terms in the claims of the formulation patents to be indefinite. The first, which stated “the topical formulation produces less than 0.1% impurity A after 6 months at 25°C and 60% humidity,” was found indefinite because “impurity A” is not known to a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA). The second, which stated “the formulation degrades by less than 1% over 6 months,” was found indefinite because the patent did not disclose how degradation was measured. The third, which stated “consisting essentially of,” was found indefinite because the patent did not list which properties were basic and which ones were novel. Specifically, the property “better drying time” was indefinite because the two methods used to evaluate drying time had inconsistent results, and therefore a POSITA would have no way of knowing which method should be used to evaluate drying time. The district court proceeded to deny Horizon’s motion for reconsideration of the claim construction because Horizon attempted to raise new arguments not raised in the hearings.

In 2017, Actavis filed a motion for summary judgment of noninfringement due to the court’s claim construction and indefiniteness determinations. Regarding the method-of-use patents, the district court found that, even where the PENNSAID® 2% and generic labels were substantially similar, because the generic label merely permitted application of a second topical agent to the knee after the solution had dried, whereas PENNSAID® 2% required it, Horizon had not shown that Actavis’s label induced infringement of the method-of-use patents. The district court thus granted summary judgment in Actavis’s favor.

Nonobviousness Finding Means No ANDA Approval

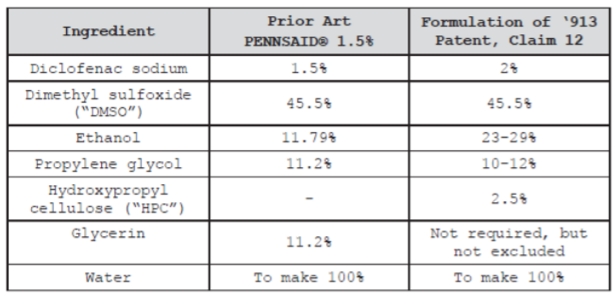

After the Markman hearings and summary judgment orders, the only claim left in dispute was claim 12 of the ‘913 patent. Actavis argued that this claim was obvious and therefore invalid, because the changes made to PENNSAID® 1.5% that resulted in PENNSAID® 2% would have been obvious to a POSITA. The table generated by the district court below describes the differences between the two.

Actavis argued that the methods used to reduce the run-off and application frequency of PENNSAID® 1.5% would have been obvious to a POSITA, and additionally, PENNSAID® 1.5% included all of the ingredients of PENNSAID® 2% sans the thickener HPC. Horizon countered this, arguing that the changes made were not routine optimizations and the results of the variations could not have been predicted by the prior art. At trial, the district court found that claim 12 was nonobvious. Because Actavis had stipulated to infringement of claim 12 if it was deemed nonobvious, the court enjoined Actavis from engaging in commercial use of the generic drug until the expiration of the ‘913 patent.

The CAFC Explores Indefiniteness

In reviewing the appeal de novo, the CAFC began by addressing Horizon’s appeal on the district court’s ruling of indefiniteness of its claims. Under Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., the Supreme Court determined that a claim is invalid for indefiniteness if its language, read in light of the specification and prosecution history, fails to reasonably inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention. Regarding “impurity A,” the CAFC agreed that the claim was indefinite because the specification does not define impurity A, nor would a POSITA know that impurity A refers to a specific impurity of diclofenac sodium as argued by Horizon. Horizon also unsuccessfully argued that the term is not indefinite because impurity A is known as the only impurity of diclofenac sodium, which is specifically termed USP Related Diclofenac Compound A RS. The CAFC argued that in depending on Claim 1, Claim 4 of the ‘913 patent refers to the degradation of the entire topical formulation of claim 1 and not the sole degradation of the active ingredient diclofenac sodium in the formation of impurity A. Therefore, a POSITA would not be able to deduce that impurity A specifically referred to the impurity USP Compound A of diclofenac sodium from the claims, especially as the written description contains no references to USP Compound A.

Horizon also argued through their expert that a POSITA familiar with pharmacopoeias, books containing a list of medicinal drugs with their effects and directions for use, would understand impurity A to be USP Compound A as identified by retention times in the HPLC system described in Example 6 of the patent. The CAFC disagreed, finding that none of the references relied upon by Horizon’s expert that use a pharmacopoeia chromatographic system omitted the details of the HPLC experiment as Example 6 did, such as the column, the mobile phase, and the flow rate. Nor did the references fail to identify USP Compound A by its actual chemical formula or structure. Therefore, the CAFC found the term “impurity A” indefinite.

Regarding the term “degrades”, the CAFC agreed that the term is indefinite because the specification did not identify the means of degradation. Additionally, the Court found that because “degrades” relies on “impurity A” and “impurity A” was found indefinite, it logically follows that “degrades” must also be found indefinite. Regarding the phrase “consisting essentially of” the Court recognized that this phrase is often used to signal a partially open claim, permitting inclusion of components not listed in the claim if they do not materially affect the properties of the invention. In this case, the specification adequately identified the five basic and novel properties of the invention:

1) better drying time;

2) higher viscosity;

3) increased transdermal flux;

4) greater pharmacokinetic absorption; and

5) favorable stability.

However, the district court found that the phrase was indefinite because the patent listed two methods to achieve better drying time with inconsistent results, therefore preventing the POSITA from having reasonable certainty about the scope of the basic and novel properties of the invention, and thereby rendering the term “consisting essentially of” indefinite under the Nautilus standard. The CAFC agreed that in using the phrase “consisting essentially of,” and thereby incorporating unlisted ingredients or steps that do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the invention, Horizon cannot escape the definiteness requirement by arguing that the basic and novel properties of the invention are in the specification, not the claims.

Extrapolating on the issue, the Court referenced PPG Industries and AK Steel in holding that courts evaluating claims that use the phrase “consisting essentially of” may ascertain the basic and novel properties of the invention at the claim construction stage, and then consider if the intrinsic evidence establishes what constitutes a material alteration of those properties. Therefore, if a POSITA cannot ascertain the bounds of the basic and novel properties of the invention, there is no basis upon which to ground the analysis of whether an unlisted ingredient has a material effect on the basic and novel properties. Additionally, although Horizon argued that “better drying time” and “better drying rate” were separate characteristics of the inventive formula, the Court found that Horizon used the terms interchangeably to refer to the residual weight of the formulation left as time progresses, thus making the property indefinite. Therefore, because the novel property “better drying rate” was indefinite, the Court found that the phrase “consisting essentially of” was likewise indefinite.

Measuring Induced Infringement

In examining summary judgment granted in favor of Actavis, the Court turned to the specific labels used for PENNSAID® 2% and the generic. Horizon argued that even though the generic claim merely permitted the use of a second topical agent on the knee instead of requiring it, as is the case for PENNSAID® 2%, Actavis’s labeling tracks closely with the asserted claims, inducing infringement whenever a user needs to apply another topical medication to the knee. Horizon argued specifically that Actavis’s warning against exposure to natural or artificial sunlight to the treated knees reflects the medical necessity of applying a topical medication such as sunscreen. Referencing Takeda Pharm. U.S.A., Inc. v. West-Ward Pharm. Corp., the CAFC explained that in order to prove inducement, evidence must be presented showing the active steps being taken to encourage direct infringement; mere knowledge about a product’s characteristics or that it may be put to infringing uses is not enough. The Court found that, where the generic label warns users who want to apply a second solution to allow the product to dry first, the label is simply operating on an “if/then” basis, which is not enough to encourage infringement of the PENNSAID® 2% product. Therefore, even though Horizon had evidence that users may infringe its product, because the generic label did not specifically induce infringement, infringement cannot be inferred.

Actavis’s Cross-Appeal on Obviousness

Lastly, the district court found that claim 12 of the ‘913 patent is nonobvious and therefore valid. Actavis contended that PENNSAID® 2% was simply a routine optimization of PENNSAID® 1.5%, and that the prior art did not need to predict the exact formulation of the asserted claim for it to be obvious. The district court found that the variables here, such as the thickener, the diclofenac sodium concentration, and the glycerin, interacted with each other in unpredictable ways, and thus a POSITA would have been challenged to predict the relative ratios of the formulation to achieve that desired goal of PENNSAID® 2%. The CAFC agreed with the district court finding that claim 12 of the ‘913 patent was nonobvious, and thus affirmed the district court’s finding that Actavis’s generic drug infringed the ‘913 patent.

Judge Newman: Majority Ruling Sows Uncertainty

Judge Newman joined the majority decision involving infringement of the ‘913 patent but dissented regarding infringement of the method-of-use claims and patent invalidity due to indefiniteness, pointing to the “inconsistency and uncertainty spawned” by the majority decision.

Regarding the phrase “consisting essentially of,” Newman found that “it is hard to imagine a clearer statement than a list of the ingredients that the claimed formulation “consists essentially of.” She argued that the majority misinterpreted Nautilus, which states that when assessing definiteness, the claims must be read in light of the patent’s specification and prosecution history. She supported this by arguing that when the properties are described in the specification, “the usage ‘consisting essentially of’ the ingredients of the composition does not invalidate the claims when the properties are not repeated in the claims.”

Next, she argued that the property of better drying time had no need for inclusion in composition claims “consisting essentially of” the listed ingredients. Her view is that recitation of the property in the specification “does not convert the composition claims into invalidating indefiniteness because the ingredients are listed in the claims as “consisting essentially of.” Additionally, she argued that the property of improved stability and its measurement need not be included in the composition claims either. She found the criticism of the indefiniteness of “impurity A” to be “untenable” because the specification adequately describes the stability to degradation by measuring the appearance of impurity A in various conditions. She went on to note that even the Actavis expert conceded that impurity A is a known degradation product of diclofenac sodium, yet even then the “degrades” term is, in her view, incorrectly held indefinite because it relies on the indefinite “impurity A.” Additionally, she argued that the majority was unfounded in precedent in distinguishing between “consisting of” and “consisting essentially of,” that the claims themselves are not indefinite, and no clear and convincing evidence existed that a POSITA would not understand the components of the composition claims with reasonable certainty. “The majority’s new ruling sows conflict and confusion,” wrote Judge Newman. “This new rule of claiming compositions casts countless patents into uncertainty.”

Lastly, Judge Newman contended that Actavis’s label induced infringement. Citing Vanda Pharm., Inc. v. West-Ward Pharm. Int’l LTD., she argued “[t]o be sure, patients may not always comply with instructions. However, this does not insulate the provider from infringement liability,” especially where the generic label instructs users to perform the patented method.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 34736435

Copyright: lightsource

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

BP

October 15, 2019 03:44 pm@1 Pro Say, agreed. Reading the decision is painful, Reyna’s approach is simply incorrect. Reyna’s and Prost’s new, judicially-created burden placed on patentees that use “consisting essentially of” in composition claims points to what they really think about patents. Newman is correct: “no clear and convincing evidence existed that a POSITA would not understand the components of the composition claims with reasonable certainty”. However, the anti-patent, activist members of the court are doing away with that standard, as seen in Taranto’s recent anti-patent decision that did away with a jury being unconvinced as to invalidity. In their few hours of review, some at the Fed Cir take joy in destroying jury efforts and months/years of careful trial work. They can’t wait for Newman to leave. She’s a brilliant scientist and jurist that stands in contrast to her anti-patent and anti-anti-trust colleagues (i.e., anti-patent is pro illegal monopoly).

Pro Say

October 14, 2019 09:27 pmWell knock me off my stool.

Judge Newman gets everything correct . . . while her colleagues do not.

Please never retire and live forever Judge Newman.

Please.

American — and indeed all — innovation needs you.