“Following the well-known Shepard Fairey case, courts have diminished the rights of photographers in their works, both by reducing the elements potentially subject to copyright and expanding the application of fair use.”

Copyrights protect original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. When photographers take pictures of individuals, there are substantial questions regarding the elements that should be attributed to the photographer’s creativity so that the work has the requisite originality for protection. Typically, the photographer’s choices regarding composition, lighting, focus, depth of field, and filtering, among many other elements, provide a sufficient basis to extend copyright protection to almost any photograph. Thus, when artists reproduce or use a photographer’s image in their pieces without permission, the photographer has a legitimate basis to complain.

Copyrights protect original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. When photographers take pictures of individuals, there are substantial questions regarding the elements that should be attributed to the photographer’s creativity so that the work has the requisite originality for protection. Typically, the photographer’s choices regarding composition, lighting, focus, depth of field, and filtering, among many other elements, provide a sufficient basis to extend copyright protection to almost any photograph. Thus, when artists reproduce or use a photographer’s image in their pieces without permission, the photographer has a legitimate basis to complain.

Today, Fairey Would Have Had Hope

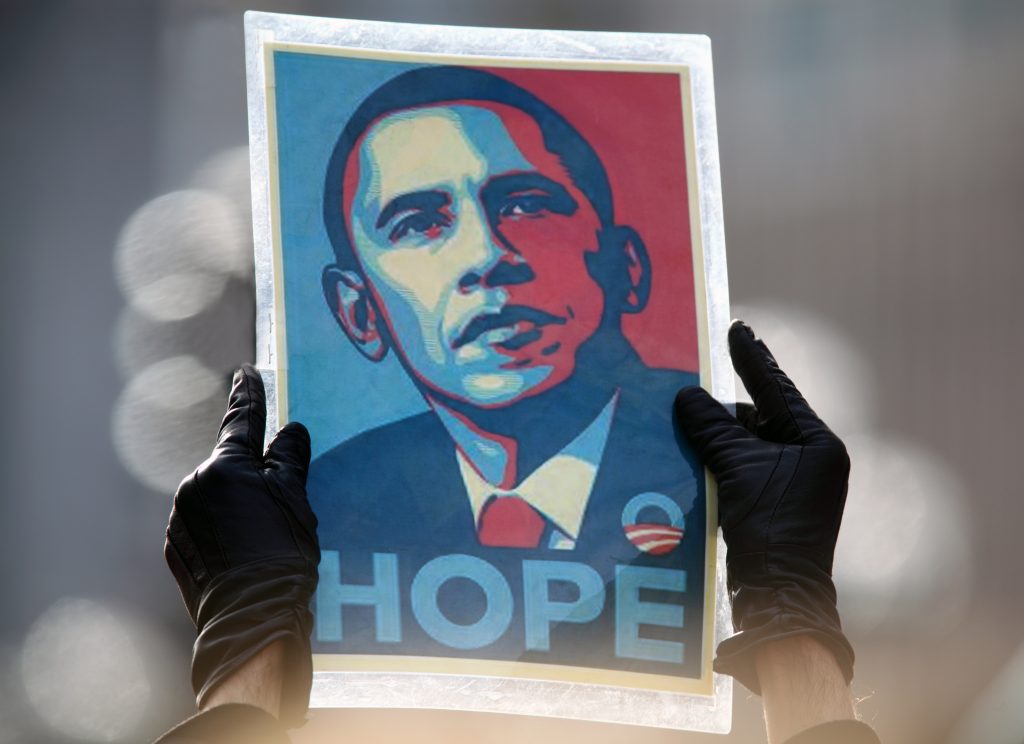

For instance, the Associated Press (A.P.) pursued the artist, Shepard Fairey, after it discovered that Fairey used an A.P. photograph of Barack Obama to make his HOPE poster, which served as an unofficial campaign image for the 2008 Obama campaign. (Click here to compare) The photograph was taken by Mannie Garcia for the A.P. at a 2006 event in which Obama was seated next to George Clooney at the National Press Club. In his defense, Fairey alleged that his work was a fair use. However, perhaps because he got scared when he was “caught”, Fairey also claimed that he used a different photograph than the one fingered by the A.P., and he destroyed evidence to hide his tracks. (Wired, Oct. 19, 2009).

Fairey may have had good reason to have been afraid, given that courts at that time had been limiting fair use to works that transformed the copyrighted original through parody or satire, which his work did not do. In fact, the judge said at a hearing in Fairey’s lawsuit that “whether it’s sooner or later, the Associated Press is going to win.” (N.Y. Times, May 28, 2010). Ultimately, the parties settled, agreeing to share proceeds from the HOPE image and to collaborate on further images. Fairey was also prosecuted by the government for tampering with evidence in the case, and was sentenced to two years of probation and fined $25,000. (N.Y. Times, Jan. 12, 2011).

After this litigation, however, courts have diminished the rights of photographers in their works, both by reducing the elements potentially subject to copyright and expanding the application of fair use. These changes are highlighted by three notable cases that photographers ultimately lost – Cariou v Prince, Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc. and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. Today, we look at the first two cases and see how they set the stage for the most recent decision regarding Andy Warhol’s portraits of the musical artist, Prince. In Part 2, the evaluation continues by addressing the Warhol case and demonstrating how, under the present legal landscape, Fairey would have had more “hope.”

Cariou v. Prince

In 2013, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals began to chip away at the rights of photographers by giving those using photographic works more ammunition to claim fair use. In Cariou v. Prince (2d Cir. 2013), the court evaluated the actions of the appropriation artist, Richard Prince, who tore out and reproduced portions of Cariou’s copyrighted photographs of Rastafarians from the book, Yes Rasta, and incorporated them into a series of his own works, titled Canal Zone. (Here is an example) The district court determined that the nature of Prince’s use of Cariou’s photographs was not transformative under a fair use analysis because it did not comment on, relate to the historical context of, or critically refer back to the original works. This conclusion was based on the Supreme Court’s decision in Campbell v Acuff-Rose, which provided that commercial parodies can meet the standards of fair use. However, in reaching this conclusion, the Court noted that when the objective of a new work “has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, … the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish), and other factors, like the extent of its commerciality, loom larger.” The district court zeroed in on this language, and assumed that a transformative purpose must have some critical bearing on the original copyrighted object, which Prince’s works admittedly did not have. In reaching this conclusion, the judge certainly was in good company. (See, e.g., Rogers v. Koons, Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corp.).

On appeal, the Second Circuit determined that the district court’s understanding of Acuff-Rose was too limited. The appeals court ruled that the overriding basis for transformation, as also discussed in Acuff-Rose, is whether the new work supersedes the object of the original creation, or instead adds something new with a further purpose or different character by altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message. From this, the Second Circuit determined that a work may be deemed transformative if it uses a copyrighted piece to create new information, aesthetics, insights or understandings, even without some commentary about the original piece. Given its broader approach, the appeals court found that almost all of Prince’s works were transformative as a matter of law because they manifested an entirely different aesthetic by altering the original serenity of the photographs into crude and jarring pieces that were much larger in size. The court concluded that Prince’s composition, presentation, scale, color palette and media were so fundamentally different that all but five of the works were definitely transformative, despite the absence of evidence that Prince used Cariou’s copyrighted images to comment on the photographer, his works or society.

Beyond seemingly expanding the concept of transformation, the Second Circuit, in Cariou v Prince, also liberalized the application of other fair use factors to again favor artists who employ copyrighted photographs in their works. Regarding the amount that may be taken, the court emphasized that an artist may take more of the copyrighted work than may be necessary for a transformative purpose, and may indeed utilize the entire work, as Prince did with some of his Canal Zone pieces, if the results have a different aesthetic character. Also, the Second Circuit made it clear that a photographer has the burden to demonstrate market harm when the alleged infringer’s target audience differs from that for the original. In other words, the court would not entertain the kinds of alternative arguments often raised by copyright owners, such as that they might have been willing to license their works to reach those new customers. Rather, photographers must provide evidence that they had already licensed or at least planned to license their works for the new artistic uses. Since Cariou could not do this, his case fell apart.

Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc.

In 1984, the photographer Jacobus Rentmeester staged a photograph of Michael Jordan dunking a basketball while in a form of grand jeté pose, in which a dancer leaps with legs extended with one foot forward and the other back. Instead of using a basketball court, Rentmeester took the picture on a grassy knoll on the University of North Carolina campus, where Jordan was then a student. Rentmeester mounted the basketball hoop on a tall pole that he planted in the ground exactly where he wished, and he positioned the camera below Jordan against a cloudless blue sky so that the hoop appears to tower above Jordan. Rentmeester instructed Jordan on the precise pose he wanted him to assume, and made many other decisions regarding such things as shutter speed and artificial lighting. The photograph originally appeared in Life Magazine as part of a photo essay featuring American athletes who would soon compete in the 1984 Summer Olympics.

Nike hired its own photographer in 1985 to produce an image of Michael Jordan that was obviously inspired by Rentmeester’s work, given that Jordan was positioned to dunk a ball while in a grand jeté pose. Nike’s photo also adopted many other important creative elements of Rentmeester’s work, including the angle which silhouettes a towering Jordan against the sky. Perhaps the most obvious differences are that Nike’s photo frames Jordan against the Chicago skyline instead of a grassy knoll and he is wearing Nike apparel. (Click here to compare the photographs)

Nike used the photo on posters and billboards to market its new Air Jordan brand shoes. When Rentmeester threatened to sue, Nike entered a two-year agreement for the right to use the Nike photo. Nike, though, allegedly continued to use the photo after this period and also adopted its “Jumpman” logo, which depicts a solid black representation of Jordan in a grand jeté pose that mirrors his image in the Nike photo. Rentmeester sued Nike in 2015, claiming the Nike’s photo and logo infringed his copyrighted work.

Many observers who assumed that this case was going to be a slam dunk for Rentmeester were shocked when the Ninth Circuit affirmed that Nike did not infringe as a matter of law Rentmeester v. Nike (9th Cir. 2018). Although Nike’s photo clearly has the same overall concept and feel as Rentmeester’s, this is not the end of the story since the photograph must also appear to be substantially similar after the unprotectible elements are factored out of the analysis. Saying this another way, if the accused photograph only shares attributes that a copyright does not protect, then that photo does not infringe. To make this determination, one has to mentally remove those elements in the copyrighted photo that are not “creative” or part of the author’s “expression”, and compare only the aspects which remain. Making this job more difficult, especially with a photograph, is that copyrights do protect original ways that an author selects and coordinates individual unprotected elements to develop a creative whole. Thus, one has to simultaneously delineate original expression from unprotected elements, and also evaluate if the unprotected elements are arranged in an original way. If one finds substantial similarity based on either of these measures, that will be enough to establish copyright infringement.

Without question, the most striking and memorable element in Rentmeester’s photograph is the unique pose struck by Jordan, emulating a ballet dancer performing a grand jeté jump. As the court admits, this is not a position that a basketball player would naturally undertake, and it is likely that no one had ever used it to dunk a ball before. Instead, Rentmeester instructed Jordan on the details of the unusual and distinctive position that he wanted him to assume as the subject of the photo. Thus, there is little question that Rentmeester’s inclusion of the pose in the context of dunking a basketball meets the standards of creativity (or originality) required by the copyright statute in that he conceived of it on his own, and did not merely discover it or copy it from somewhere else.

The Copyright statute, however, requires that an individual element of a work not only be creative, but also that it be considered part of the author’s expression of an idea, as opposed to being the idea, itself. This leads to the monumental problem of delineating ideas from expressions in copyrighted works, a task that has plagued scholars and jurists from the very beginning of copyright jurisprudence. In a nutshell, the idea for any work can be conceived anywhere along a spectrum that ranges from a very general notion to one that is very specific. For instance, the idea for a novel could be as simple as to convey a mystery, or it might be much less abstract, so as to include many of the story’s specific plot developments and characters. The courts have devised several guideposts that sometimes help with this determination, such as the merger doctrine and scènes à faire, but ultimately the decision is ad hoc.

The Ninth Circuit determined that with regard to Jordan’s pose, Rentmeester’s idea was to capture the player attempting to dunk a shot while holding a basketball above his head in the left hand with his legs extended in a posture loosely based on the grand jeté. That meant that the only elements of expression in the pose were secondary details such as bends in the limbs, which were slightly different in the two photographs. Unfortunately, the court made no attempt to explain why it landed on this delineation of the idea from the expression. It simply stated it as if it had to be true. But, of course, the idea could have been conceived in many other ways. For instance, the idea could have been to simply to create a picture of Michael Jordan, or Jordan leaping with a basketball, or Jordan leaping while attempting to dunk the ball, or Jordan leaping with an unusual posture, or Jordan leaping with a dance move, or Jordan leaping with a ballet dance posture, and so on. If the idea were conceived on any of these terms, then the choice to use the grand jeté jump would then have been expression, thus making copyright infringement much more likely.

According to the court, Rentmeester’s photograph also included other unprotectible ideas, such as the decision to use an outdoor setting stripped of most traditional trappings of basketball and a camera angle that captures the subject silhouetted against the sky. One might take particular issue with the characterization of the outdoor setting for the same reasons that the choice of using a grand jeté leap might not necessarily be an idea. Use of the camera angle, on the other hand, might not be protectible, in and of itself, not so much because it is an idea, but rather for lack of originality. In any event, even if all these elements (pose, setting and camera angle) were independently unprotectible, then Rentmeester’s decision to select and combine the three characteristics nonetheless could still be considered an original expression worthy of copyright protection. Yet the court stated that Rentmeester cannot claim an exclusive right to these separate concepts, even in combination. So, when all of these salient elements were removed from consideration, all that was left were details such as the skyline, the sun, lighting and shadows, and Jordan’s position in the photo. By looking past the dominant similarities and focusing on the remaining items, the court determined that Nike’s photograph differed enough with the protectible expression in Rentmeester’s work to escape liability for copyright infringement. In addition, Nike then prevailed regarding the “Jumpman” logo since it was merely a solid black silhouette of Nike’s noninfringing depiction of Jordan.

After this decision, photographers continued to face disappointment when Lynn Goldsmith lost her copyright case against the Andy Warhol Foundation. We’ll take a look at how this happened in Part 2 of this series.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Photography ID: 14552885

Copyright: jhansen2

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Lee Burgunder

October 18, 2019 01:36 pmThank you, BP. Please tell your nephew, who it sounds is still at Cal Poly, to drop by and say hello sometime.

Stephen Stern

October 16, 2019 02:02 amGreat read and analysis, Lee. Thanks for sharing your insight – truly transformative!

BP

October 15, 2019 10:09 pmThank you! (and IPWD/Gene et al. too) Great post. Of course I am biased by the fact that two nephews attended CalPoly, one in business, who is rocking it. I look forward to Part 2. I’m glad you mentioned Rogers v. Koons because that is on point. What’s up 2nd Circuit? Given its decision in Prince, today, Koons would have won no problem! While I see little merit in Prince’s work (don’t get it), Koons stands as a giant for exposing the banality of US culture, furthering Warhol’s foresight into consumerism/marketing of today’s “influencers” where we have, behind the curtain, so-called “technology” monopolies that are little more than psyops advertising/social media manipulators (that BTW have taken over/usurped most of copyright law). Today, if Prince prevails, Warhol is a slam-dunk (let’s say a jumpman). However, what’s so hard about licensing? Cough up some money for the photographers, they’re artists too.