“None of this bodes well for personal photographers, especially those who work diligently with their subjects to create unique images that exude a particular sense of style and personality.”

In my previous post, I explored how times have changed for photographers who once appeared to have the upper hand in copyright infringement disputes with appropriation artists and others. As discussed there, the high-water mark for photographers may have been several years ago, when the Associated Press used its leverage to reach a settlement with Richard Fairey regarding his Obama Hope poster. However, since then, photographers have suffered a series of losses, beginning in 2013 with Cariou v. Prince and continuing in 2018 with Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc.

Capturing Prince

The most recent case to strike a blow against photographers is The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (S.D.N.Y. 2019). Lynn Goldsmith is a noted photographer of musical artists who specializes in capturing her subjects’ true selves through interpersonal methods and special photographic techniques. In 1981, she did a photo shoot of the performer, Prince, for which she specially applied facial makeup to support her feeling that Prince was in touch with his female side while also being very much male. She made many choices regarding the equipment, lighting and background to emphasize certain of Prince’s physical attributes, such as his chiseled bone structure. According to Goldsmith, the photographs from this session depict a man who was not a comfortable person and was a vulnerable human being. (See Goldsmith’s photo here)

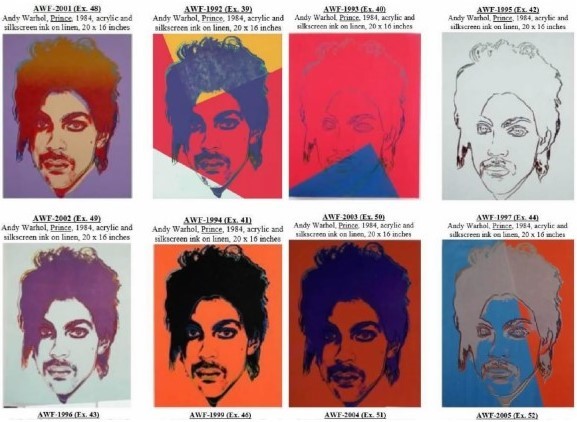

In 1984, Goldsmith’s agent licensed one of the black-and-white studio portraits to Vanity Fair, which is owned by Condé Nast, for use as an artist’s reference in connection with a forthcoming article, titled “Purple Fame.” The magazine commissioned Andy Warhol to create a full-color illustration of Prince based on the photograph, and his work appeared with the article and on the table of contents. Warhol ultimately used the photograph to create a series of Prince works that included twelve silkscreen paintings, two prints and two drawings. (Here are some examples)

After Prince died in 2016, Condé Nast published a commemorative issue for which it licensed one of Warhol’s pieces to appear on the cover. This is when Goldsmith first learned about Warhol’s Prince pieces and she informed the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) that the Condé Nast cover violated her copyright. AWF then brought suit for a declaratory judgment that Warhol’s series of works were not infringing, claiming that they were not substantially similar in expression and that, in any event, they were a fair use.

A Foregone Conclusion?

The district court judge, John Koeltl, first determined that he did not need to evaluate the question of substantial similarity because he felt that Warhol’s works were clearly protected by fair use. In this regard, Judge Koeltl addressed the fair use factors, beginning with the purpose, which he concluded was transformative. Koeltl followed the direction in Cariou and noted that there was no requirement that Warhol’s pieces comment on Goldsmith or her photographs to meet the standard. He also concluded that Warhol’s alterations to the original photo gave it a different character by transforming Prince from a vulnerable person to an iconic larger-than-life person. According to Judge Koeltl, Warhol did this by removing his torso, softening his bone structure, and overall making him appear as a flat, two-dimensional figure rather than the detailed three-dimensional figure in Goldsmith’s photograph. Warhol also added loud and unnatural colors to several of the works, which contrasted with the original black-and-white image.

At this juncture, one might question whether the judge was already in the process of reaching a conclusion that he felt obliged to make. After all, a decision in favor of Goldsmith might tarnish the reputation of an American icon. Indeed, the Second Circuit had already strongly signaled in Cariou that it believed that Andy Warhol’s works were transformative because they comment on consumer culture and explore the relationship between celebrity culture and advertising. Judge Koeltl also emphasized that each of the works in the Prince series are immediately recognizable as a “Warhol” rather than as a photograph of Prince, demonstrating to him, at least, that some meaningful transformation had taken place. Of course, this is a spurious argument, since then any artist could satisfy the requirement of a transformational purpose simply be adding a consistent flourish or paint stroke that essentially serves as a personal trademark. But I doubt that this is what the Supreme Court meant when it talked about giving a work a further purpose or different character.

Judge Koeltl also believed that at the end of the day, Warhol used very little of the creative elements in Goldsmith’s photograph, and that what he took was reasonable to achieve his legitimate transformational purpose. As previously noted, Warhol cropped the photograph, albeit slightly, and also changed several attributes, including the lighting, background, sharpness and color, so as to wash away Prince’s sense of vulnerability. Of course, Warhol took the most important attribute of Goldsmith’s work—the actual recorded image of Prince, including his facial features and pose. Although Goldsmith worked hard to have Prince manifest the precise look that she desired, the judge determined that most of what she achieved in her photograph was not protectible expression. The court ruled that an individual’s pose in a photograph is an unprotected idea, rather than expression, which harkens back to the conclusion also reached by the Ninth Circuit with Michael Jordan. In addition, according to Koeltl, Prince’s facial features were not copyrightable. None of this, of course, bodes well for personal photographers, especially those who work diligently with their subjects to create unique images that exude a particular sense of style and personality.

Photographers Now Have Less Hope

When Shepard Fairey faced litigation in 2009, he feared that he would lose, since he appropriated the AP’s copyrighted work without having an intent to comment on the specific image, the photographer, or the AP He thus worried that his work was sufficiently similar to be infringing and that he could not meet the standards for fair use. However, it is clear that in today’s environment, he would have little reason to be concerned.

To begin, the AP might not be able to prove substantial similarity of expression. Based on the recent cases, a photographer seemingly has no copyrightable interest in an individual’s pose, even when the photographer has a significant role with supervising the subject’s posture and demeanor. Mannie Garcia only captured an image of Barack Obama, so he certainly had less claim to a copyrightable interest than either Rentmeester or Goldsmith had with their works. This means that the potentially protected expression is limited to things like shutter speed, camera angle, focus, cropping and color. However, if Rentmeester’s choice of camera angle did not meet the standard of originality, there is no way that Garcia’s view would satisfy it. Also, other attributes of the photograph are arguably typical in the field of news reporting and thus may not be original. And, of course, Fairey changed the composition of colors in his work. So perhaps that would be the end of the story, but I doubt that a court would rest on it, since Fairey’s poster so clearly meets today’s standards for fair use.

Given the results in Cariou and Warhol, my guess is that the AP would not seriously entertain a suit against Richard Fairey, had he created his Hope poster today. As mentioned, the artist no longer must demonstrate that a work qualifies as a parody or satire; rather it is enough that the work has a further purpose or different character for it to be transformative. The Hope poster clearly meets this standard by converting a realistic photo into a symbol of American idealism. And although Fairey took much of the photograph, that probably does not matter, since the appropriation was still reasonable to fulfill the transformative objective. This is especially true in light of the decision in Warhol, where the artist arguably incorporated more creative copyrightable elements than did Fairey. I also imagine that the A.P. would have no more luck proving market harm than did Cariou or Goldsmith.

Despite Limits on Fair Use, Photographers Take Noticeable Hit

So, clearly the world has changed for photographers, at least when dealing with individuals who are not simply interested in raw duplication of their images. Nonetheless, there still are limits to how far appropriation artists and others can push the envelope. For instance, Richard Prince took it too far when he simply enlarged Instagram photos, added brief comments, and printed them on stark white backgrounds. (Graham v. Prince). Likewise, a court ruled that a film production company infringed when it merely cropped a copyrighted photograph of the Adams Morgan neighborhood in Washington, D.C. to promote an upcoming film and music festival. (Brammer v. Violent Hues Productions, LLC). But despite these successful outcomes, it is clear that photographers have taken a noticeable hit to the copyrights in their works. Hope, they say, springs eternal, but perhaps not so much for photographers anymore.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

BP

October 19, 2019 06:17 pmGreat post – and a little tidbit, guess who represented Graham against Prince, it was the former Director of the USPTO, David Kappos. The backstory on Garcia’s image was also insightful. However, I understand that Mannie Garcia did not only capture an image of Barack Obama in that he captured two people, a politician (Mr. Obama) and a celeb. Given the original, I’d say Garcia certainly has a “thick” copyright (thick to the composition but thin to Obama alone?). Does “fair use” care whether it’s thick or thin?