“Following the takeover by SoftBank, the valuation of WeWork has dropped almost overnight from over $47 billion to $8 billion (as of the writing of this article). Since the fundamentals of the company haven’t changed, the drop can only be attributed to one thing: a decline in the value of the brand.”

In an article we published on this blog in November 2015, we documented the findings of a study of Unicorns (startups with valuations of over $1 billion) and their patent holdings. In that study, we discovered that over 60% of Unicorns held immaterial patent portfolios (10 assets or less). We have subsequently concluded that these Unicorns are likely to fill the gap in their patent holdings through organic filing and patent acquisitions, as they approach an exit event or as they enter a major new market.

In an article we published on this blog in November 2015, we documented the findings of a study of Unicorns (startups with valuations of over $1 billion) and their patent holdings. In that study, we discovered that over 60% of Unicorns held immaterial patent portfolios (10 assets or less). We have subsequently concluded that these Unicorns are likely to fill the gap in their patent holdings through organic filing and patent acquisitions, as they approach an exit event or as they enter a major new market.

Fast forward to October 2019, and WeWork, a member of our Unicorn “Class of 2015”, has been in the news under very unpleasant circumstances. The WeWork planned IPO was called off in October 2019, after questions emerged related to, among other things, the viability of the company’s business model following financial and operating disclosures included in its S-1 filing with the SEC. This led to a series of events where, eventually, SoftBank acquired a controlling interest in the company at a valuation of $8 billion, a fraction of its most recent valuation of $47 billion, while in the process removing Adam Neumann, the company’s co-founder and CEO, and buying out his shares.

While WeWork did not engage in any significant patent filing or buying, unlike Uber or some of its other peer Unicorns from the “Class of 2015” study, there is a very interesting IP angle to the WeWork story. Much of the company’s marketing communications activities have been dedicated to portraying it as a “technology company.” As a matter of fact, the company describes itself in its S-1 filing as follows: “We provide our members with flexible access to beautiful spaces, a culture of inclusivity and the energy of an inspired community, all connected by our extensive technology infrastructure.” In the startup world, association with technology leads to higher valuation multiples and considerable interest from investors (particularly if you are a player in a “low-tech” industry such as commercial real estate). In this article, we set out to explore whether WeWork is truly a technology company, what types of IP assets it holds, and how these assets have played a role in its valuation before and after its failed attempt at an IPO.

26x Multiple on Revenues: Innovative Business Model or Valuation Bubble?

Founded in 2010, WeWork (recently renamed the “We Company”) has gained traction in the shared-office space category. Led by flamboyant co-founder, Adam Neumann, the company aims to disrupt the long-term, fixed price model of commercial real estate leasing by offering fractional spaces under flexible lease terms. The office spaces have been leased by WeWork from office building owners, remodeled to a certain cool aesthetic standard, repackaged into leasable units ranging from one desk to an entire floor, and marketed to renters looking for flexible lease terms while enjoying the perks of communal services and socializing. With the proliferation of freelancing, entrepreneurship and telecommuting, the WeWork business model provided a working space for people with unconventional or unpredictable working needs.

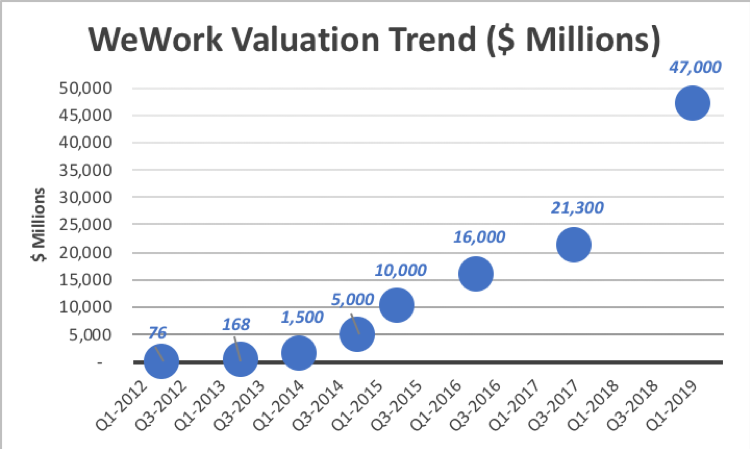

WeWork has raised over $10 billion since 2012, from a host of investors including VC funds, banks, mutual funds and eventually, SoftBank’s Vision Fund. With every funding round, the valuation of the company increased, crossing the Unicorn threshold at $1.5 billion in December 2014, and accelerating to $47 billion in January 2019 (over 30x increase in valuation in four years), as seen in the chart below. The company filed to go public in August 2019, and its S-1 filing reported key performance indicators (KPIs) including: over 528 locations in 111 cities across 29 countries, 527,000 members and 1.9 million workstations in the pipeline. The S-1 filing also reported $1.827 billions in revenues for fiscal year 2018, which, at a valuation of $47 billion in January 2019, implied a staggering multiple on revenues of 26x.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

If the WeWork business model sounds familiar, it is probably because it is by no means a new business model. Switzerland-based IWG PLC (LSE: IWG.L), known for its RegusTM shared office and co-working locations, has been in business since 1989 and competes with WeWork in many of the same markets (the company operates other brands including: Regus Express, Spaces, Signature, Kora and Open Office brands). A review of the IWG financial results reveals that, while IWG’s trailing twelve months (TTM) revenues as of Q2-2019 were £2.7 billion, its market capitalization as of October 31, 2019 has been only £3.4 billion. IWG had more locations in more cities and across more countries as compared with WeWork, and yet the market capitalization of IWG indicates a multiple of only 1.4x on revenues, a far cry from the 26x multiple by which WeWork raised funding in early 2019.

Is WeWork a Technology Company?

This type of revenue multiple premium enjoyed by WeWork is often attributed to a “technology” factor, which usually describes some unique intellectual property that justifies a higher multiple for companies, particularly when they are disrupting traditional industries where very little innovation had taken place over the years. A couple of well-known examples of the technology premium are the difference between Uber and a taxi company, or between Airbnb and a hotel chain. Both companies, being the poster child of the new paradigm known as the “shared economy”, represent the harnessing of technological advancement to turn an existing business model upside down.

One interesting aspect that is worth exploring is whether WeWork is indeed a “technology” company, as its inflated pre-IPO valuation multiple implies? Or is it holding some other type of IP assets that warrant a higher valuation as compared with its older, more-established competitor?

A review of the WeWork S-1 filing looking for IP holdings, R&D activities or technology acquisitions, points to very little indications of technology development or IP ownership:

- No significant patent portfolio – The S-1 contains very limited and generic references to patents, under a section titled “Our Intellectual Property (p. 169) – where it is stated: “In order to maintain our competitive position, we rely on both trade secret and patent protection”. The section then concludes with the following sentence: “To further capture our inventive output, we secure our innovation through patent protection. From enhanced mapping features on our member app to workspace optimization to robotic construction, we seek to obtain patents within diversified fields of invention”. As previously discussed, we have been following WeWork, along with a peer group of US-based Unicorns, since 2015. WeWork was among the group of about 60% of all Unicorns in the US who, at the time of conducting our original study in 2015, held 10 or less patent assets (granted or published applications). As of the writing of this article, WeWork does not seem to have made much progress with regards to its patent holdings. A recent search on patent analytics platform Innography, reveals that the company had only 8 active patent assets, including 2 US granted patents that came through an acquisition, and 6 pending application in the US and worldwide. Compared with companies like Uber, Lyft, Snap and DropBox, who have embarked on patent filing and buying campaigns which have significantly increased their patent portfolios, WeWork has done none of the above. Furthermore, upon review of WeWork’s 8 active patent assets, they seem to be very loosely correlated with enhanced mapping or robotics, as indicated in the S-1 quote above. Most of the pending applications are related to lighting solutions (covering inventions related to light bulb with LED filament), and the two issued patents are related to the detection and analysis of pedestrian traffic within a predefined area (both of which were obtained through WeWork’s acquisition of Euclid in February 2019).

- No significant investment in R&D – a search for “R&D” in the S-1 filings reveals very few entries and no significant disclosures. When reviewing the Income Statements for 2016-2018, one can find the investment in R&D embedded in a cost item called “Growth and new market development expenses”, which on a cumulative basis over the 3 years accounted for only 12% of overall expenses. A deeper dive into the financial statements reveals that this particular cost item includes a hodgepodge of expenses of all types including: “design, development, warehousing, logistics and real estate costs, expenses incurred researching and pursuing new markets, solutions and services, and other expenses related to the Company’s growth and global expansion”. If there is any of the traditional R&D activities associated with the creation of IP in a technology company, then they are buried in a way the is not discernable, and are likely immaterial. As far as the output of the company’s R&D efforts, there has been only one new published patent application filed since 2017 related to a reservation system. All other organic filings occurred through patent applications filed in 2017.

- No significant technology acquisitions – finally, many high growth companies fill in the technology gap by acquiring other companies. Particularly when it comes to Unicorns, the company grows so quickly, and is often times so focused on gaining market share, that it doesn’t always have time to grow its IP portfolio to capture all new technologies that are needed for its growing business. Many Unicorns apply some of their massive funding rounds, particularly in the later stages, to acquisitions. Based on its S-1 filing, in the 2017-2018 period, WeWork has spent close to $900 million on acquisitions. Most of the money ($480 million) was spent on acquiring Naked Hub Holdings, a China-based co-working office space company. The other large acquisition ($156 million) was the 2017 acquisition of MeetUp, a community of user groups with common interests, which could be considered an acquisition based on market share synergy, not necessarily driven by technology (anecdotally, none of MeetUp’s 13 active patent assets, including 10 US grants, appear to have been assigned to WeWork). The remaining acquisitions were mostly of smaller companies offering services ancillary to the company’s core office sharing business (marketing, web development, meeting management), none that ended up adding a significant technological advantage or IP position to the company.

WeWork’s Main IP Asset is Its Brand

With immaterial patent holdings, little investment in R&D and virtually no technology acquisitions, does WeWork have any IP assets that would justify the significant valuation multiple it had pre-IPO? While WeWork may not qualify as a traditional “technology company”, there is still intellectual property that may explain at least some of the inflated valuation multiple: the company’s brand.

In the Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations segment of the S-1 filing, there is a segment (page 169) titled “Our Intellectual Property”. The first line of that segment reads as follows: “We believe that our brand is critical to our success. Accordingly, we spend a significant amount of time and resources protecting our brand identity”. The company then continues to review its various trademarks (WE, WEWORK, WEGROW and WELIVE), while also discussing the company’s efforts to police its portfolio of trademarks around world. It also mentions the company’s more than 1,500 global domains. There is no mentioning of technology, patents or innovation until the end of that section, where there is one sentence stating that: “Our proprietary innovation supports our growth and brand”. Interestingly, WeWork sees the innovation as supporting the brand, and not the other way around. It is very clear from the language of the S-1, based on what the company itself chose to highlight in its Intellectual Property disclosure, that the main IP asset of this company is its brand (including the IP rights/properties supporting it, like trademarks and domain names).

It is somewhat rare to become a household name in the commercial real estate business. According to the National Real Estate Investor’s ranking of top office owners for 2018 (ranked by the volume of office space owned), the top 5 names on the list are: Blackstone Group, Brookfield Properties, LaSalle Investment, Tishman Speyer and Hines. All of these have very little brand recognition. Even Regus, the brand competing with WeWork, has been around since 1989 but has none of the strong name recognition and prestige associated with the WeWork name.

WeWork has certainly been very active around managing and expanding its brand. The company has re-branded as the “We Company” in early 2019, a move aimed at expanding the business segments it operates in under the We umbrella: WeWork for office leases, WeLive for co-living residences, and WeGrow for education. These are classic strategies of “brand extension”: taking an already strong brand and leveraging on its strength to expand into new lines of business. The S-1 even revealed a somewhat disturbing story about Mr. Neumann returning $5.9 million worth of stock that was originally paid to him by the company to acquire the trademark “We” that he obtained under an affiliated entity under his control.

Interestingly, it should be noted that the IWG has sued WeWork in 2018 for trademark infringement, related to the use of the “HQ” mark in WeWork’s new service line “HQ by WeWork” aimed at providing a flexible working space for mid-size companies. IWG claimed that this could cause confusion in the marketplace with their own brand “HQ Global Workplaces”. The parties ended up settling the lawsuit later that year.

What is Next for WeWork?

Following the takeover by SoftBank, the valuation of WeWork has dropped almost overnight from over $47 billion to $8 billion (as of the writing of this article). Since the fundamentals of the company haven’t changed, the drop can only be attributed to one thing: a decline in the value of the brand. From a multiple on revenue perspective, the company is still overvalued at multiple on revenue of 4.4x, relative to its competitor, IWG which is traded at 1.4x on revenue. Given the operating metrics of both companies, one can only conclude that the WeWork brand has not entirely lost its value, although it has definitely suffered a major devaluation.

We started out exploring whether WeWork is a technology company and have concluded that technology is not the main IP asset for WeWork, but rather its brand is. Since the brand seems to have lost most of its value, it is hard to see it propelling the company into extreme valuations as seen earlier this year. There is disagreement among industry observers as to whether the business model of WeWork can ever show profits, given its exposure to long term lease agreements and the need to fill the space with short term leases. Now, more than ever, WeWork will need to evaluate its business model fundamentals, as those will be under scrutiny by its investors and shareholders. Any plans for an upcoming IPO look unlikely given the shift in corporate ownership and governance. It remains to be seen if and how this company will emerge from this crisis.

The main takeaway from this story, when it comes to investing in high tech companies, is the need to exercise caution and not take the company’s statements at their face value without checking under the hood as to what technology the company has really developed or acquired. It is a cautionary tale for many investors who believe they invest in technology, or in a business model disrupted by technology, and are willing to pay a very high valuation multiple for that investment. Technology does not come out of thin air: if there are no indications of investment in R&D, no efforts made towards the creation of an IP portfolio, and no resources allocated to technology acquisitions, then there probably is not much of a technology platform to speak about, even if the company claims otherwise.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Photography ID: 299089210

Copyright: [email protected]

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

11 comments so far.

Night Writer

November 13, 2019 03:56 amI guess the trademark issue is important like McDonald’s. If you want to lease short-term office space and you can be sure to get a square deal maybe you go to WeWork.

One of the biggest reasons people like Uber over taxis is the fee is set before you start the trip. None of the anxiety of the taxi driver playing games with you, which they often did to me.

Efrat Kasznik

November 12, 2019 05:12 pm@TFCFM – thank you for your feedback! I try to stay away from populistic comparisons. I actually don’t think there is much in common between WW and Theranos, unless you consider the fact that there was a charismatic leader leading both, which made fundraising relatively easy! I don’t think venture capital investors are all fools, either. There are entire branches of economics and psychology dedicated to investor behavior and what is driving them. Some like to use the term “herding” or “FOMO” (fear of missing out) when discussing the rush to invest in companies like WW or Theranos. That being said, my blog was focused on IP, and when it comes to IP, there is a big difference between a biotech company like Theranos, and a real estate company like WeWork. Life sciences companies are based on R&D, so there is no question as to whether there is a “technology” foundation (whether it is legitimate technology or made-up test results, that’s a different story). In the case of WeWork, there is a basic question as to whether it is a “technology” company. My conclusion is, it’s not. So the question then becomes, do they have any IP and if so, what? I have concluded, they have a brand image that is sustaining their growth. So that’s why I have not used Theranos as a benchmark for WeWork.

Efrat Kasznik

November 12, 2019 05:02 pm@Kenichi – thank you for sharing your blog! We have been looking at Unicorns and IP since 2015, when we did the original study that is quoted in the blog. Since then we have done some follow up studies, including a study of Unicorns who went public (Uber included), and how their patenting behavior has changed. There are reasons why a company like Uber had very few patents in 2015, and has many more patents now. There are several theories that explain the low patent count in Unicorns, and why some of them change their behavior and start pursuing patents more aggressively as they approach an exit event or a new market. It largely goes to lifecycle, industries you operate in, and the people running the IP function in your organization. Both Uber and WW grew valuation to tens of billions without patents – that’s an undisputed fact. Uber is in a different place in its lifecycle than WeWork (post IPO), and has started buying to backfill its portfolio, as well as invest in organic filing, several years ago. Uber is also competing in industries (autonomous vehicles) where a patent position is critical (unlike real estate, where it is not). Finally, Uber brought over a team of IP professionals that understand the strategic importance of patents. At the end of the day, it’s very much about the people….

Efrat Kasznik

November 12, 2019 01:46 pm@Night Rider – Uber and WeWork are two very different companies with very different business models. The one thing they have in common is that they took a large investment from SoftBank and reached big scale in their respective industries, so people – seeing that both companies are struggling (one could not pull and IPO, the other did, but is struggling in the stock market) – tend to compare them to each other. I could write another 2,000 word blog just on how these two companies differ (and maybe I will, if Gene has space for another blog 🙂 It’s not about the app… an app is not a business model, nor a technology – it’s a communication channel. I will probably write more about this, so stay tuned!

TFCFM

November 12, 2019 09:55 amI am impressed that the author was able to write the article without using the word “Theranos,” even as I wonder why she avoided the comparison. It seems to me that both Theranos and WeWork involve the same characters:

– fools,

– their money, and

– a “business model” that seems like it might be a good idea, unless you think about it.

Kenichi N Hartman

November 12, 2019 09:22 amEfrat – Thanks for the analysis! I posted a FB post back on Oct. 27 just comparing the number of granted US patents assigned to WeWork vs. Uber, but didn’t have the bandwidth to go deeper (too busy with my day job of drafting and prosecuting patent applications). I’m thrilled to see someone like you give this issue the full treatment 🙂

For reference, here’s a copy of my Oct. 27 FB post:

“I saw some comparisons being made between Uber and WeWork on the questions of “is it a tech company?”, so decided to take a back-of-the-envelope look at their respective patent portfolios. Did a quick search on Google Patents, which listed 423 granted US patents having Uber (“Uber Technologies, Inc.”) as an assignee. A similar search for patents assigned to WeWork pulled up… 1 granted US patent, which was not developed internally and assigned to WeWork a few months ago.

I realize that the number of patents is hardly the only metric for tech innovation, but that’s a big difference.”

Night Writer

November 12, 2019 07:55 am@4 Efrat

Really good analysis. The Uber app solves a problem and enables new things. While there is just no story of what WeWork does where there is a new technology that changes anything. I guess the idea is a app where the people can put commercial space up for rent with short term leases (like the drivers in Uber) and the people needing short-term office space (like the riders of Uber).

So I guess that is the best possible way to understand their business model. I am just not sure there is a huge demand for short-term lease office space. And why do you need their app to find the short-term office space. Seems like there is an argument (to play the devil’s advocate) for WeWork, but I feel like there is no huge demand like in Uber (both lots of people that will drive and lots of people that want rides.) I think in WeWork there is not the great demand on both the rent and renters side.

Efrat Kasznik

November 11, 2019 08:32 pmProSay, thank you for the nice feedback! Commercial building owners have already been moving a small portion of their properties into the shared-office space, based on what I have read, some of them working with WeWork’s competitors to manage these spaces for them. If this was a profitable business model, landlords would have been all over it: they could have directly leased smaller spaces for shorter periods without the WeWorks of the world acting as middlemen. The problem is, the fluctuations in the rental market, which is why long-term leases are the norm in this business. The landlords were probably sitting back and watching this madness go on, knowing fully well this business model has no sustainability….

Pro Say

November 11, 2019 04:57 pmThanks Efrat — nice analysis.

Given all the recent very bad news, no barrier to entry (any commercial building owner could easily replicate what they do), and severe overspending, “WeWork” is a misnomer.

Try: WeDon’tWork

Efrat Kasznik

November 11, 2019 01:58 pmNight Writer, thank you for your comment! There are at least a dozen companies they could have acquired in the $900 million they spent on acquisitions, even if they had no R&D or no patenting strategy. The possibilities are many, but the focus was elsewhere (some might say, nowhere….)

Night Writer

November 11, 2019 11:55 amThanks for writing this. A bit surprising as it seems there is so many possibilities for technological innovation in their space.