“In the early 2000s, teams of scientists produced 64% of all scientific papers and teams of inventors were responsible for 54% of patents. By the second half of the 2010s, the comparable figures were 88% and 68%.”

Innovative activity is more collaborative and transnational, but also focused on a few large clusters in a few countries. These are among the findings in the latest World Intellectual Property Report, published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) on November 12.

The report focuses on the geography of innovation, using geocoding based on the addresses of inventors listed on patents and the locations of the authors of scientific articles and conference proceedings.

Hotspots

Source: WIPO

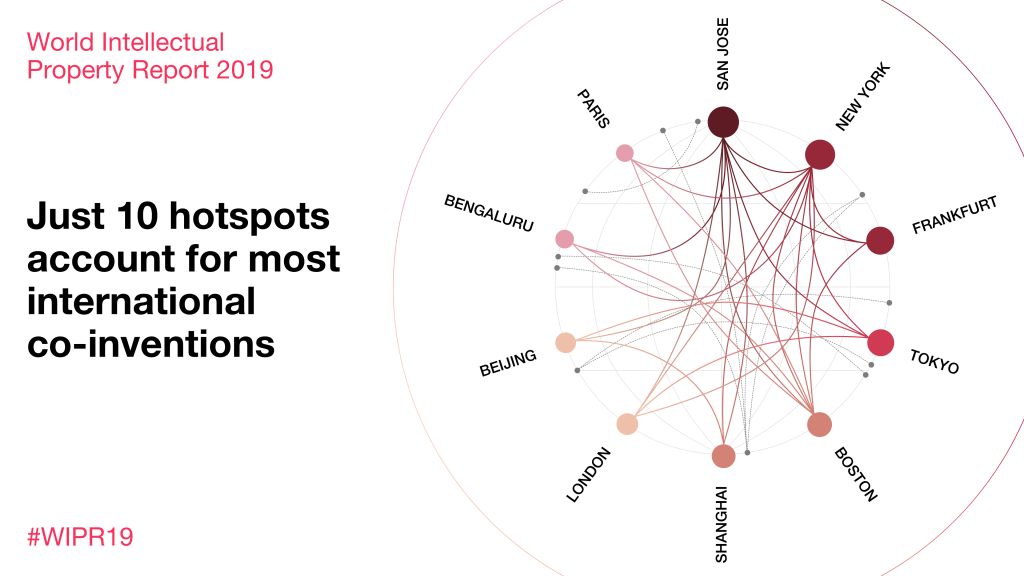

The report found that, during the period 2015-2017, some 30 metropolitan hotspots accounted for more than two-thirds of all patents and nearly half of scientific activity. The top 10 hotspots worldwide are: San Francisco/San Jose, New York, Frankfurt, Tokyo, Boston, Shanghai, London, Beijing, Bengaluru and Paris. In the U.S., hotspots around New York, San Francisco and Boston accounted for about a quarter of all U.S. patents filed from 2011 to 2015.

Going Global

The report found that, in general, innovation has become more international in the past 20 years. Before 2000, Japan, the United States and Western Europe accounted for 90% of patenting and more than 70% of scientific publishing. But these shares fell to 70% and 50%, respectively, for the 2015-17 period, due to growth in countries such as China, India, Israel, Singapore and the Republic of Korea.

However, scientific activity remains more widespread than patenting. Many universities and other research organizations in middle-income economies generate large numbers of scientific publications (often in collaboration with partners in the United States and Europe) but these economies account for relatively few patents.

More Collaboration

Another key finding in the report is that innovation has become more collaborative in the past 15 years. In the early 2000s, teams of scientists produced 64% of all scientific papers and teams of inventors were responsible for 54% of patents. By the second half of the 2010s, the comparable figures were 88% and 68%. In general, however, international collaboration is still more frequent in scientific publishing than in patenting.

Bigger Teams

Moreover, the size of teams is growing: in 2017 the average scientific paper involved almost two more researchers than 20 years previously. In patents, the average team number has doubled since the early 1970s. By the mid-2010s, two-third of all inventions were collaborative efforts.

At the same time, collaboration has become more international, led by the U.S. and Europe. In the period 2011 to 2015, the U.S. and Western Europe accounted for 68% and 62% of all international inventive and scientific collaboration. New entrants from other countries mostly collaborate with the United States and Western Europe rather than with each other.

Inventors and scientists within hotspots and niche clusters collaborate internationally more than those outside, particularly when it comes to scientific articles. The report also suggests that U.S. hotspots are among the most connected, even compared to cities such as Tokyo or Seoul which have larger or similar scientific or inventive output.

Case Studies

Source: WIPO

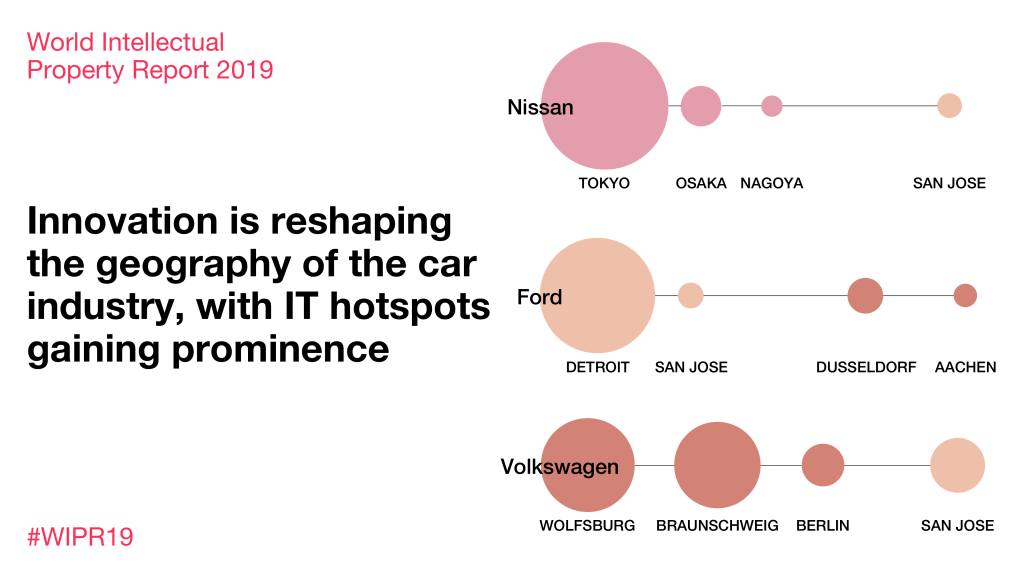

The report includes two case studies, on the automotive industry and agricultural biotechnology. It also looks at geographical trends in corporate R&D, for example, finding that the proportion of patents with foreign inventors filed by U.S. companies increased from 9% in the 1970s and 1980s to 38% by the 2010s. In the 2010s, more than a quarter of all international patents sourcing by U.S. multinationals had an inventor from China or India.

Takeaways

In the foreword to the report, WIPO Director General Francis Gurry said it shows how “globally intertwined” innovation has become. He added: “The report makes the case for maintaining policy openness and further strengthening international cooperation. Solving increasingly complex technological problems will require ever larger and more specialized teams of researchers. International collaboration helps form such teams and will therefore be indispensable in continuously pushing the global technology frontier.”

The report was supervised by WIPO Chief Economist Carsten Fink and prepared by a team form WIPO’s Economics and Statistics Division. It also draws on background papers commissioned for the report from external researchers. The dedicated page on WIPO’s website provides links to the launch webcast, press release, photos, key findings and interactive maps.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

12 comments so far.

Anon

November 25, 2019 10:50 amMaxDrei,

Please do not attempt to switch the topic (especially as in-artfully as you do here, conflating eligibility and patentability in a completely separate case).

Your “half-joke” remains at variance with the replies.

MaxDrei

November 24, 2019 08:42 amAmerican Axle is a nice case for discussion of abstractness. US 7774911 and EP-A-1994291

https://register.epo.org/application?number=EP07751339&lng=en&tab=main

I mean, the patent itself explains that it was well-known that hollow drive shafts suffer from three vibration modes and that a liner is conventionally used to damp vibrations. The claimed invention is to “tune” the design to manage unwanted vibrations. As if there ever was a time when designers iterated towards an optimal design. What could it be, eligible for patenting, that the invitation to “tune” brings to the PHOSITA that was not already well-understood by that person? A rose by any other name is not a patentable invention.

The good patent brings the PHOSITA something he/she did not already have. The bad one, by contrast, affects to deprive that reader of what they already had. The hard bit is finding a pragmatic and reliable way to filter out the bad ones.

BTW, the AA patent names a slew of individuals, as having conceived the concept of “tuning”. What else would one expect from a corporate Applicant?

Anon

November 24, 2019 08:30 amSorry MaxDrei, but your position remains unclear.

I still cannot tell from your comments here (and your history of comments), what your position is in regards to computing innovation (and the notion that computing innovation has a strong tie to innovation from the individual).

MaxDrei

November 24, 2019 04:56 amIn reference to my “good with their hands” I was thinking of abstract inventive concepts versus computer-implemented inventions (not always abstract) versus “anything under the Sun made by the hand of man” (most definitely not “abstract”).

Perhaps the joke (played on all of us) is to say that “abstract” is what defines the boundary between which inventive concepts are patentable and which are not?

Then, in the context of patentability, there’s the notion of “useful”. I had in mind that end users (also of computer-implemented inventions) have a reliable sense of what is useful to them.

Anon

November 23, 2019 06:41 pmMaxDrei,

It is unclear which half is the joke.

Perhaps crossing in transit, Ternary’s post at 5 provides a sharp distinction to the notion you present of single inventors being very hands-on in a physical machine sense.

If anything, one who understands innovation and the entire reason for the advent of the design choice of “wares” in computing to move from “hard” to “soft” would readily grasp Ternary’s point.

Ternary

November 23, 2019 03:57 pmThat is a ridiculous statement, MaxDrei. Even if half joking.

MaxDrei

November 23, 2019 01:05 pmWho can still make inventions single-handedly? Those who use machines, have an ultra-keen interest in optimising the performance of those machines, and are good with their hands. Examples: agricultural engineers and brain surgeons. I’m only half joking.

Ternary

November 23, 2019 12:07 pm“But these days, to come up with an enabled, new and non-obvious contribution to a crowded art you nearly always need teamwork.” Thanks for articulating it like that MaxDrei. It is a prevalent opinion nowadays. And in a sense it may be true.

I brought up “single inventors” with a director of a large research facility and referred to Hugh Aitken’s book Syntony and Spark. He told me bluntly that the “golden time” of individual inventors (as in electronics) was over. No important invention could be made by a single inventor anymore. The future for innovation was in institutionally organized R&D.

But nobody appears to have an explanation, why that is. It is especially noteworthy that many inventors who make comments on IPWatchDog are actually single inventors. I am one.

I believe at least one of the reasons is the way we now organize R&D, which depends on proposals, peer review, budgeting, and the always required “teamwork.”

There is of course no objective reason why a novel contribution cannot be made by a single inventor. There always is a first inventor. It is just that the organization compels the first inventor to involve others.

There are many barriers, some created deliberately, to discourage the single inventor. The trick is, from my own experience, to get the inventor going. A first invention, with some exceptions, is for many inventors not the best one. But for many, a first invention open the floodgate of new ideas. Especially because one does not have to deal with negative feedback (“that will never work”) from peers and superiors. That does not mean that some feedback would not be useful. But basically, there is no “organization” that stops the independent inventor to proceed.

Right now, the current patent system is an importance barrier for independent inventors to proceed with their activities. Caught up in useless discussions about eligibility and prohibitive costs to assert patents and get at least some compensation is stopping and preventing independent inventors to pursue their inventive activities. Eventually the inventor will stop working as an independent operator.

I personally have no problem at all to come up with enabled, new and non-obvious inventions in a crowded art. One of the reasons is that it is in computer-implemented technology. I only need a computer and some software to test and tune my ideas. I have the Internet to check on prior art. And I am ruthless in dropping ideas that have been used before. I am not unique in that. This is of course what has happened on a large scale in the computer industry. And it is what compelled the incumbents who are threatened by it to put (successfully) a stop to it. And who now say that organized R&D is the way forward.

Pro Say

November 23, 2019 10:15 amThanks James, Ternary, and Max — good info and observations all.

MaxDrei

November 23, 2019 05:19 amIs there a misunderstanding here, between “individual” and “independent”? Ternary doubts that as much as 20% of all patent applications are filed by independent inventors. So do I. I think the WIPO data reveals that in 20% of patent applications, the Applicant entity (ie the owner) names only one individual as the inventorship entity. in the remaining 80% of applications, there is joint inventorship by a team of at least two inventors.

That seems to me about right. It used to be more, of course. But these days, to come up with an enabled, new and non-obvious contribution to a crowded art you nearly always need teamwork.

Anon

November 22, 2019 06:29 pmThanks Ternary.

Ternary

November 22, 2019 12:31 pmNice summary Mr. Nurton. From an independent inventor’s point of view the report is not good news. This report almost completely ignores the key role of the independent inventor. When it mentions independent inventors it says “Historical accidents involving unusual individuals.” I don’t believe at all that great inventions by individual inventors are “historical accidents.” But we live in a time wherein such a belief is becoming more entrenched and is perhaps not even worth noting.

The report correctly identifies “Multinational companies lie at the center of the web.” An allegation that has been often argued at IPWatchDog.

A surprising number in the report is that 20% of patent applications comes from individual inventors. That seems very high to me. And perhaps driven by the fact that no assignee is usually provided in a patent application. The USPTO number on issued patents to independent inventors in 2018 is about 7% of total.

The report also notes that there is a “falling R&D productivity.” Not an unusual event in the history of technology that is dominated by institutions.

Overall, the report confirms the existing bias against individual inventors. Not by disparaging that group, but by focusing on “geography.” Corporations are very good at convincing governments that “addressing corporate interests” will drive economic development. I am not against institutional R&D. But history shows that innovation is a human endeavor, not an institutional one.

The report tells that the strategy of concentrating R&D power to companies and institutions is working. It also indicates that there will be an increasingly smaller return on R&D due to that concentration.

Innovation requires recalcitrant, original and obstinate individual thinkers. They are a pain in the neck for institutions. No doubt about it. They upset hierarchies, strategies and group thinking. With the enormous, no gigantic, amount of information easily available on-line one would expect an explosion of new ideas and inventions reflected in patent applications. But the opposite is true. The establishment is geared to suppression of new ideas that threaten institutional interests. That is not new. It is just puzzling how successful those efforts have been and are.