“In essence, Samsung’s argument is that there is no limit to the Board’s authority to make unpatentability determinations at the conclusion of an IPR proceeding. That position is at odds with both the statutory language and the case law, and we reject it.” – Federal Circuit opinion

The Federal Circuit in a precedential decision issued earlier today affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s finding that Claim 11 of Prisua Engineering Corp.’s U.S. Patent No. 8,650,591 was unpatentable as obvious, and reversed and remanded for further consideration the Board’s finding that the other asserted claims were indefinite and could not be assessed for patentability under Sections 102 or 103. The opinion was authored by Judge Bryson.

The Federal Circuit in a precedential decision issued earlier today affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s finding that Claim 11 of Prisua Engineering Corp.’s U.S. Patent No. 8,650,591 was unpatentable as obvious, and reversed and remanded for further consideration the Board’s finding that the other asserted claims were indefinite and could not be assessed for patentability under Sections 102 or 103. The opinion was authored by Judge Bryson.

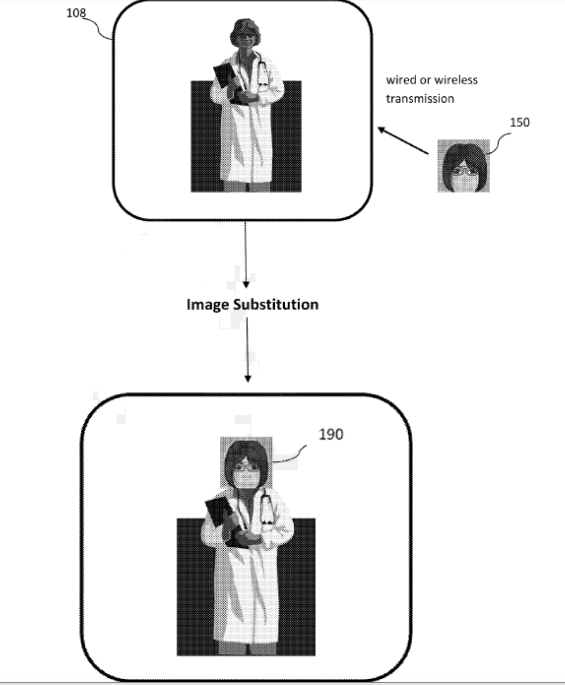

Claims 1–4, 8, and 11 of the ’591 patent were at issue in IPR2017-01188, which was brought by Samsung in March of 2017. The claims are directed to methods and apparatuses for “generating a displayable edited video data stream from an original video data stream,” by substituting one object for another. For example, “a user can insert a selected image, such as a face of the user’s choosing, in place of the face of the figure in the original video,” as illustrated below.

IPR2017-01188 was Samsung’s response to Prisua’s 2016 patent infringement lawsuit against the company, which alleged that Samsung’s “Best Face” feature infringed claims 1, 3, 4, and 8 of the ’591 patent.

In that case, a jury in the Southern District of Florida ultimately found that Samsung had willfully infringed the asserted claims and awarded Prisua $4.3 million in damages, but that action was stayed pending the CAFC appeal.

“The ‘Best Face’ feature, according to Prisua, allowed the accused devices to capture a burst of images and then replace unwanted facial images, such as images captured when someone was blinking, with better images from other frames in the same burst,” explained the CAFC.

PTAB Adds Claims Following SAS Institute

The PTAB initially instituted the IPR only on Claim 11, explaining that it could not determine the scope of the other claims. But as briefing in the IPR was nearing an end, the Supreme Court issued its decision in SAS Institute, Inc. v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 1348 (2018), in which the Court held that IPRs must be instituted on all asserted claims, or none.

The Board thus modified its institution decision to include all the challenged claims and all the grounds presented in the petition, ultimately holding that Samsung had not demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence that claims 1-4 and 8 were unpatentable.

Here is the language of claim 1 in full:

1. An interactive media apparatus for generating a displayable edited video data stream from an original video data stream, wherein at least one pixel in a frame of said original video data stream is digitally extracted to form a first image, said first image then replaced by a second image resulting from a digital extraction of at least one pixel in a frame of a user input video data stream, said apparatus comprising:

an image capture device capturing the user input video data stream;

an image display device displaying the original video stream;

a data entry device, operably coupled with the image capture device and the image display device, operated by a user to select the at least one pixel in the frame of the user input video data stream to use as the second image, and further operated by the user to select the at least one pixel to use as the first image;

wherein said data entry device is selected from a group of devices consisting of:

a keyboard, a display, a wireless communication capability device, and an external memory device;

a digital processing unit operably coupled with the data entry device, said digital processing unit performing identifying the selected at least one pixel in the frame of the user input video data stream;

extracting the identified at least one pixel as the second image;

storing the second image in a memory device operably coupled with the interactive media apparatus;

receiving a selection of the first image from the original video data stream;

extracting the first image;

spatially matching an area of the second image to an area of the first image in the original video datastream, wherein spatially matching the areas results in equal spatial lengths and widths between said two spatially matched areas; and performing a substitution of the spatially matched first image with the spatially matched second image to generate the displayable edited video data stream from the original video data stream.

The Board held that claim 1 and its dependent claims invoked section 112, paragraph 6, with respect to the “digital processing unit” element, and that because there was no corresponding structure in the specification, the Board could not apply the prior art to the claims.

“For example, similar to the ‘distributed learning control module’ considered in Williamson [v Citrix], here, ‘digital processing unit’ does not recite sufficiently definite structure,” wrote the Board.

PTAB is Not Authorized to Cancel Claims for Indefiniteness

Samsung argued that the Board should have canceled the claims based on its determination that they were indefinite under the Federal Circuit’s analysis in IPXL Holdings, LLC v. Amazon.com, Inc.

But the CAFC rejected Samsung’s contention that the IPR statute authorizes the Board to cancel challenged claims for indefiniteness, citing Cuozzo Speed Techs., LLC v. Lee, in which the Supreme Court said that the USPTO would be acting “outside its statutory limits” by “canceling a patent claim for ‘indefiniteness under § 112’ in inter partes review.”

In fact, the statute does not permit the Board to institute inter partes review of claims for indefiniteness, said the Court, pointing to Section 311(b), “Scope,” which states that “[a] petitioner in an inter partes review may request to cancel as unpatentable 1 or

The CAFC said:

In essence, Samsung’s argument is that there is no limit to the Board’s authority to make unpatentability determinations at the conclusion of an IPR proceeding. That position is at odds with both the statutory language and the case law, and we reject it.

Indefiniteness Does Not Preclude Patentability Analysis

However, the CAFC agreed that the PTAB should have assessed the patentability of claims 1-4 and 8 and that the Board’s holding that the “digital processing unit” element of the claims was subject to section 112, 6 was incorrect, and reversed on that point.

We agree with Samsung that the term “digital processing unit” is not a “means-plus-function” limitation subject to analysis under section 112, paragraph 6. Because the reference to the digital processing unit does not contain the words “means for,” there is a rebuttable presumption that section 112, paragraph 6, does not apply to that limitation.

That presumption can be overcome, but only “if the challenger demonstrates that the claim term fails to ‘recite sufficiently definite structure’ or else recites ‘function without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function.’”…. The Board pointed to no evidence that a person skilled in the relevant art would regard the term “digital processing unit” as purely functional.

On remand, the Court said that the Board should “should address Samsung’s argument that the Board may analyze the patentability of a claim even if that claim is indefinite under the reasoning of IPXL.”

Even though the validity of the challenged claims may be subject to question for IPXL-type indefiniteness, that is simply another ground on which the claims might be challenged in an appropriate forum (other than the Board). It does not necessarily preclude the Board from addressing the patentability of the claims on section 102 and 103 grounds. In the remand proceedings, the Board should determine whether claim 1 and its dependent claims are unpatentable as anticipated or obvious based on the instituted grounds.

With respect to the PTAB’s obviousness finding on claim 11, the CAFC found that none of Prisua’s arguments on cross-appeal had merit.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

TFCFM

February 5, 2020 10:40 amPEC’s “victory” may prove pyrrhic.

I question the value of obtaining an IPR decision that that says that “claim X is so indefinite that we can’t tell what it means, but nonetheless the petitioner did not prove that the claim (whatever it means) was anticipated or obviated by patents or printed publications.”

Why not just paint concentric red-and-white circles on the not-formally-invalidated claim?

angry dude

February 4, 2020 08:05 pmThis is a clusterf^&* everybody (except the wealthiest corps) should avoid

Screw US “patent system”!

Pro Say

February 4, 2020 07:55 pmOnce the unconstitutional “judges” fix their 112 boo-boo (assuming of course they follow the CAFC’s direction), their decision needs to be made precedential by a POP.

102 and 103 analysis only under IPRs means 102 and 103 analysis only.

Not 112. Not 101. Not any other patentability requirement.

Thankfully, the CAFC got this right.

Anon

February 4, 2020 07:38 pmTrojan fellow one: What a beautiful gift horse — let’s pull it right into the city.

Trojan fellow two: I don’t know — where did our besiegers get so much wood?

Ternary

February 4, 2020 07:24 pm“The Board held that claim 1 and its dependent claims invoked section 112, paragraph 6, with respect to the “digital processing unit” element, and that because there was no corresponding structure in the specification, the Board could not apply the prior art to the claims.”

How so a “digital processing unit” is purely functional? One of ordinary skill would have realized immediately that a computer, a processor, or an FPGA would fall under this term. The specification teaches a “programmable computer apparatus.” Were is: “one of ordinary skill would have known,” that was used to invalidate another patent? Don’t we know anymore how data is processed by a machine? Do we really believe that this is indefinite and it prevents one of ordinary skill to make or use the invention? Of course not. Samsung proving the point with infringement. They were not precluded from infringing because they had no idea of the corresponding structure related to a “digital processing unit.” It is merely a nice “gotcha” that replaces a potentially disappearing Alice.

This is a warning on what to expect when modified 112(f) wording becomes law. For this you don’t even need SCOTUS to deny inventors a valid patent.

True, it is sloppy claim drafting by Prisua. But is the claim indefinite? Enough to kill the patent? Not on this matter: it isn’t and it shouldn’t.

Anon

February 4, 2020 05:33 pmWhat a cluster.

The entire notion of Post Grant Review needs to be revisited.