“Seinfeld teaches that prudent counsel should inquire whether copyright authorship or ownership is disputed.”

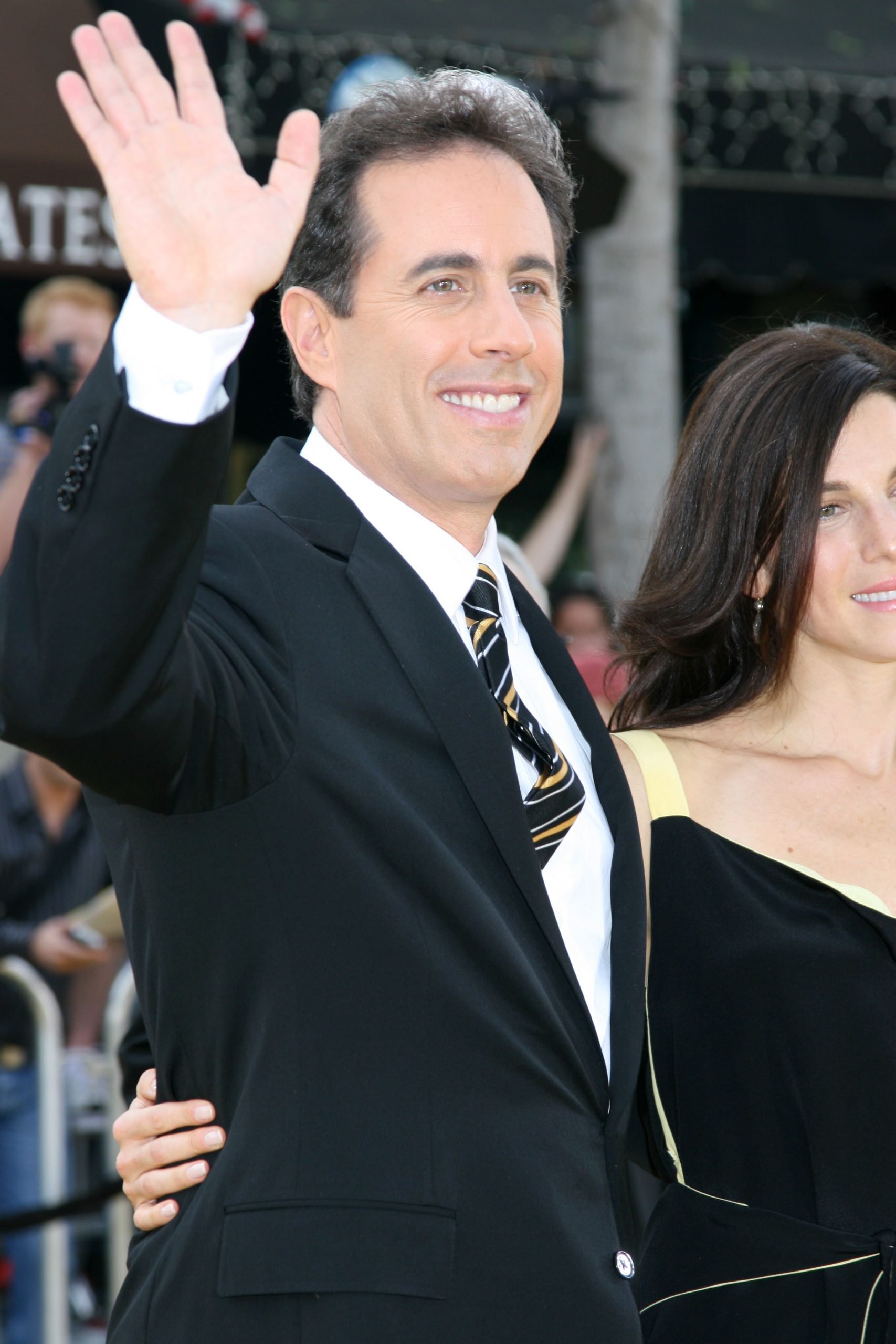

You may have seen a web series featuring Jerry Seinfeld called Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. The basic premise of the show is that Seinfeld and another famous comedian take a drive in a classic car and stop along the way at a coffee shop to share stories. It’s essentially a moving talk show without an audience. Examples of comedians who’ve appeared on the show include Tina Fey, Jim Carrey, Stephen Colbert, Chris Rock, Eddie Murphy, Jimmy Fallon and many others. One notable exception to the guest being a comedian occurred when then-sitting President Obama was Seinfeld’s guest. The series debuted on the Sony-owned Crackle video streaming platform and moved over to Netflix for its tenth season in July 2018.

You may have seen a web series featuring Jerry Seinfeld called Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. The basic premise of the show is that Seinfeld and another famous comedian take a drive in a classic car and stop along the way at a coffee shop to share stories. It’s essentially a moving talk show without an audience. Examples of comedians who’ve appeared on the show include Tina Fey, Jim Carrey, Stephen Colbert, Chris Rock, Eddie Murphy, Jimmy Fallon and many others. One notable exception to the guest being a comedian occurred when then-sitting President Obama was Seinfeld’s guest. The series debuted on the Sony-owned Crackle video streaming platform and moved over to Netflix for its tenth season in July 2018.

What you may not know is that there has been litigation surrounding the series. On February 9, 2018, plaintiff Christian Charles filed a lawsuit in federal court in New York City alleging copyright infringement and related claims against Seinfeld and a number of other defendants involved in the series. The case is Christian Charles v. Jerry Seinfeld et al., United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, Case No. 18-cv-01196. The following facts are taken from Charles’s Second Amended Complaint (i.e., this is Charles’s version of events, not Seinfeld’s).

Facts Alleged In Second Amended Complaint

Charles describes himself as a writer and director who worked with Seinfeld on various projects since 1994, including “award-winning American Express commercials featuring Seinfeld.” In 2000, Charles claims he suggested to Seinfeld “filming two friends driving and talking in a car as a unique television show.” About a year later, Charles claims he created a treatment for the project and referred to it as Two Stupid Guys In A Stupid Car Driving To A Stupid Town. Seinfeld passed on Charles’s Two Stupid Guys treatment, but the two continued to work together on various projects from 2002 to 2011, including in connection with marketing of the Bee Movie.

In July 2011, according to Charles, while meeting with Seinfeld about potential new projects for Seinfeld, “Seinfeld suggested to Charles that a show about comedians driving in a car to a coffee place and just ‘chatting’ could work, to which Charles immediately pointed out this suggestion was actually Charles’s Two Stupid Guys Treatment, which Charles had pitched to Seinfeld in 2002.” According to Charles, he and Seinfeld “agreed to develop further Charles’s Two Stupid Guys Treatment, with Charles developing, directing, and producing the project.” Charles then created a Comedians in Cars Going for Coffee treatment, which he presented to Seinfeld in September 2011. According to Charles, “Seinfeld enthusiastically agreed to move forward.” Charles then performed additional work resulting in a “Script,” and his production company, mouseROAR, shot a pilot of the show. Charles continued work on the project during the remainder of 2011.

Then, in January 2012, Charles became concerned when he learned of discussions with another production company, Embassy Row owned by Sony Pictures Television. Charles felt involving Embassy Row “would be counterintuitive to Charles’s and Seinfeld’s business arrangement that mouseROAR would provide all of the production services.” Eventually Charles was told that he would need to negotiate terms for himself and mouseROAR with Embassy Row. During those negotiations, Charles communicated his “request for compensation and backend involvement” with the series. According to Charles, when Seinfeld heard about Charles’s request, “Seinfeld called Charles and expressed outrage at the notion that Charles would have more than a ‘work-for-hire’ directing role.” Charles further alleged that “Seinfeld further claimed that Charles’s request was ‘ungrateful’ and ‘out of line,’ and that Charles should expect to be compensated through his directing fee.” Charles and Seinfeld spoke by telephone again a few days later but continued to disagree. Charles alleged that he never “discussed work-for-hire arrangements or received, reviewed, or executed work-for-hire agreements.” He further alleged Seinfeld did not (until years later) claim authorship or ownership of the Pilot, and that Charles often reminded Seinfeld that the idea for the show was Charles’s.

According to Charles, after the last phone call, “Seinfeld refused to engage in good faith discussions with Charles about the Project,” but others close to Seinfeld assured Charles he would “remain involved,” “it would all blow over,” and “not to worry.” In April 2012, a Seinfeld representative communicated via voicemail that “It’s not over; Christian and Jerry can still work together.” While Seinfeld agreed to pay $107,734 for certain mouseROAR production expenses, and there were some discussions between representatives of Charles and Embassy Row about potential back end compensation, that never materialized, and Charles’s involvement in the project ended.

Charles alleged that for the remainder of 2012 through 2014, the defendants used and copied Charles’s materials without authorization. Nevertheless, according to Charles, “[d]uring this time, Charles maintained the reasonable and good faith belief, pursuant to their 18-year creative and business relationship and assurances from Seinfeld’s personal and professional colleagues, that Seinfeld would eventually acknowledge Charles’s authorship and ownership and bring him in on the Project.” However, in “September of 2016, Charles concluded that Seinfeld never intended to include Charles on the Project, either as director or creator of the Treatment, Pilot, and Script, or to recognize his marketing and distribution strategy.” That same month, Charles registered his Treatment with the U.S. Copyright Office.

In early 2017, Charles learned of a deal to move the series to Netflix. At the end of 2017, “Charles sent a letter directly to Seinfeld and communicated the need for mediation to resolve the outstanding issue of Charles’s involvement with the Project.” In early 2018, Seinfeld’s counsel “responded in writing to Charles’s letter and stated that Seinfeld was the creator and owner of the Project.” According to Charles, “[a]lthough Seinfeld had previously claimed to be the creator of [the series] in the press, [his counsel’s] letter was the first time Seinfeld or a representative of Seinfeld had directly made this claim to Charles.” Shortly thereafter, on February 9, 2018, Charles filed his lawsuit against Seinfeld and the other defendants for copyright infringement and related causes of action.

The Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

In response to Charles’s lawsuit, the defendants filed a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim, arguing that Charles’s claims were barred by the statute of limitations.

The district court began its analysis by reciting that copyright infringement actions have a three-year statute of limitations. Charles v. Seinfeld, 410 F. Supp. 3d 656, 659 (S.D.N.Y. 2019). The district court then listed the two basic elements of a claim for copyright infringement, those being (1) ownership of a valid copyright, and (2) copying of the original elements of the work. Id. A key point in the court’s analysis was that Charles’s claims disputed the first element (ownership). Id. As such, the limitations analysis was necessarily focused on the ownership element as opposed to the copying element. This was critical to the district court’s reasoning, since the outcome would have been different if the case had been only about continued copying.

Framing its limitations analysis around ownership, the district court cited Kwan v. Schlein, 634 F.3d 224, 229 (2d Cir. 2011), and stated: “The Second Circuit has held that when ‘ownership is the dispositive issue’ in an infringement claim and the ‘ownership is time-barred,’ then the infringement claim itself is time-barred, even if there has been infringing activity in the three years preceding the lawsuit.” Charles, 410 F. Supp. 3d at 659. Charles attempted to distinguish Second Circuit authority by arguing (1) his lawsuit is about “authorship” and not “ownership,” and (2) his lawsuit disputed the defendants’ status as owner, whereas the Second Circuit authority addressed a plaintiff’s status as owner. Id. The district court was not persuaded by either argument. Id.

The district court then set out to determine when Charles’s ownership claim accrued. In that regard, the district court stated that “[t]he ownership claim accrues only once, when a reasonably diligent plaintiff would have been put on inquiry as to the existence of a right.” Id. at 660 (citations and internal quotation marks omitted). The district court relied on two facts alleged by Charles, which occurred more than three years before the lawsuit was filed, to conclude that Charles’s ownership claim accrued outside the limitations period.

First, “in 2011 Seinfeld rejected Charles’s request for backend compensation and made it clear that Charles’s only involvement was to be on a ‘work-for-hire’ basis.” Id. The district court reasoned that Seinfeld’s rejection “necessarily contradicted any idea that Charles was the owner of intellectual property in the show.” Id. The district court further noted that it was of no moment that Seinfeld did not claim ownership at that time. Id. It was sufficient that Seinfeld repudiated Charles’s claim. Id. Charles attempted to blunt Seinfeld’s repudiation by pointing to statements made by Seinfeld associates, such as, “It’s not over; Christian and Jerry can still work together.” Id. The district court disagreed, stating those comments only related to whether Charles “would remain involved in the Project;” those comments did not “plausibly contradict Seinfeld’s statements that Charles would not be ‘involved’ on more than a work-for-hire basis.” Id.

Second, the district court found it important that Charles was aware that the series was being produced and distributed without crediting Charles. The district court concluded this fact was sufficient to put Charles on notice that Seinfeld had repudiated Charles’s claim of authorship. Id.

In view of these two facts, the district court concluded that Charles was aware since at least 2012 that his ownership claim had been rejected. Id. Accordingly, the district court concluded that Charles’s claim of ownership accrued more than three years before the lawsuit was filed, and his copyright infringement claim was therefore time-barred. Id. at 661. The court likewise concluded that Charles’s related copyright claims were also time-barred and declined to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over his state law claims. The court therefore dismissed the federal claims with prejudice, and dismissed the state law claims without prejudice.

Charles’s Appeal to the Second Circuit

Charles appealed the district court’s decision to the Second Circuit. The Second Circuit concluded “that the district court was correct in granting defendants’ motion to dismiss, for substantially the same reasons that it set out in its well-reasoned opinion.” Charles v. Seinfeld, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 14596 *2 (2d Cir. May 7, 2020). The court further elaborated regarding Charles’s argument that his lawsuit did not center on ownership, stating “that argument is seriously undermined by his statements in various filings throughout this litigation which consistently assert that ownership is a central question.” Id. The court concluded “the central issue is clearly a dispute over ownership, as opposed to a dispute over whether subsequent iterations of that show make use of the material in the script for the pilot.” Id. at *3. In determining that Charles’s ownership claim was time-barred, the Second Circuit agreed that either of the two facts relied on by the district court – (1) Seinfeld’s rejection of Charles’s claim for backend compensation and that Charles’s compensation would be limited to a work-for-hire basis, or (2) commercializing the show without crediting Charles – were sufficient to place Charles on notice of his ownership claim outside the limitations period. Id. The Second Circuit accordingly affirmed the district court’s judgment.

Key Takeaway

Attorneys considering potential copyright litigation should not rely solely on continuing acts of copyright infringement when evaluating the three-year statute of limitations. Rather, Seinfeld teaches that prudent counsel should inquire whether copyright authorship or ownership is disputed. If so, a thorough investigation of the facts and timeline related to such dispute should be conducted to determine when the plaintiff’s authorship or ownership claim accrued, and litigation should be initiated accordingly.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Copyright: Jean_Nelson

Image ID:13001990

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-banner-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-938x313-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Joseph Lakanal

June 25, 2020 07:30 amUS courts have developed some persistent confusions on copyright matters. Section 507 bars actions for infringement after three years. But disputing someone’s ownership of copyright is not an infringing act (especially in the US which provides rights of paternity only to visual artists). Every unlicensed act is a new infringement until the expiry of the copyright.