“[T]he CAFC noted that common sense is critical in determining obviousness and ‘rules that deny factfinders recourse to common sense are inconsistent with our case law.’”

On June 26, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed a final written decision of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board in B/E Aerospace v. C&D Zodiac, Inc. In particular, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s conclusion that the asserted patent claims would have been obvious because a modification of the prior art was nothing more than a predictable application of a known technology and because a modification would have been common sense.

The Patents

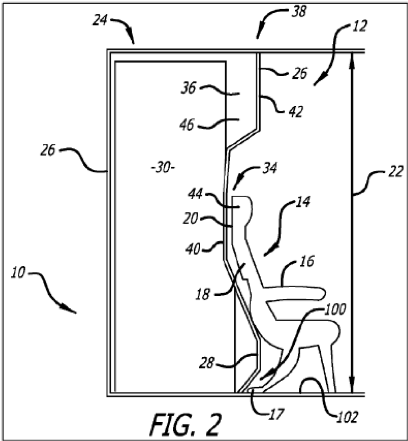

B/E Aerospace, Inc. (B/E) was the owner of U.S. Patent No. 9,073,641 (the ’641 patent) and U.S. Patent No. 9,440,742 (the ’742 patent), which were directed to space-saving modifications to the walls of aircraft enclosures including contoured walls designed to “reduce or eliminate the gaps and volumes of space required between lavatory enclosures and adjacent structures.”

Claim 1 of the ‘641 patent, which the parties agreed was representative of the challenged claims, was directed to an aircraft lavatory for a cabin of an aircraft, and recited, in part, a lavatory unit including a forward wall portion “shaped to substantially conform to the shape of the … inclined seat back of the passenger seat, and includes a first recess [34] configured to receive at least a portion of the … inclined seat back of the passenger seat therein, and further includes a second recess [100] configured to receive at least a portion of the aft-extending seat support therein when at least a portion of the … inclined seat back of the passenger seat is received within the first recess.”

Proceedings Before the PTAB

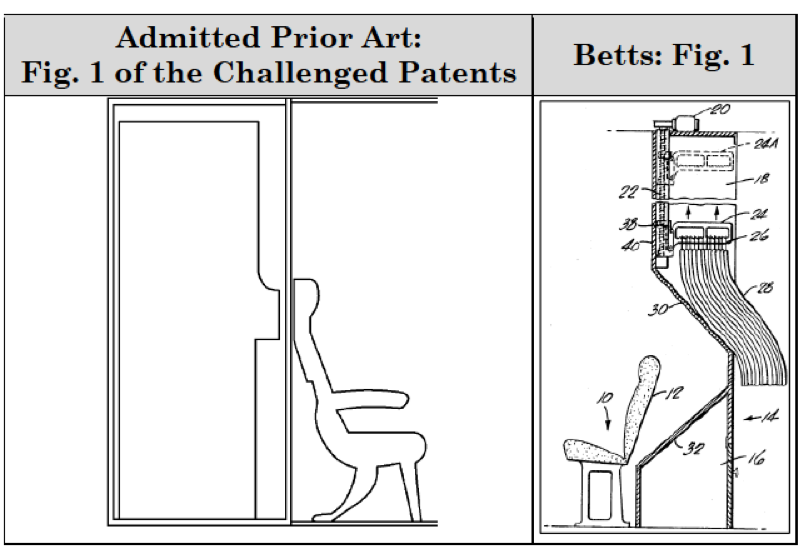

Zodiac, Inc. (Zodiac) filed a petition requesting an inter partes review (IPR) of the ’641 and ’742 patents, wherein Zodiac asserted that the challenged claims were obvious over portions of the asserted patents, i.e. Admitted Prior Art and U.S. Patent No. 3,738,497 (Betts).

Betts disclosed an airplane passenger seat having a coat closet behind the seat with a luggage space 16 and overhead coat compartment 18. The coat closet was defined by a contoured wall for accommodating the seat’s tilted backrest, which the Board determined met the “first recess” claim limitation of the asserted claims. The Admitted Prior Art, i.e. Figure 1 of the asserted patents, disclosed “a flat, forward-facing lavatory wall immediately behind a passenger seat that has a rear seat leg extending toward the back of the plane”. The PTAB determined that it would have been obvious for a skilled artisan to modify the flat wall of the Admitted Prior Art with the contoured wall of Betts “because skilled artisans were interested in adding space to airplane cabins, and Betts’s design added space by permitting the seat to be moved further aft.”

Based on the arguments presented by Zodiac, the Board also determined that it would have been obvious to further modify the Admitted Prior Art and Betts combination to include a “second recess to receive passenger seat supports”. First, Zodiac argued, and the Board agreed, that that it was an “obvious solution to a known problem” to create a recess in a wall to receive a seat support. Zodiac presented expert testimony that the addition of a second recess “is nothing more than the application of a known technology (i.e., Betts) for its intended purpose with a predictable result (i.e., to position the seat as far back as possible).” Second, the Board agreed with Zodiac that “it would have been a matter of common sense” to incorporate a second recess in the combination of Admitted Prior Art and Betts because recesses configured to receive seat supports “were known in the art”.

Zodiac attached three design drawings to its petition in support of its assertions that lower recesses to receive a seat support were “known in the art.” B/E filed a motion to exclude the design drawings because Zodiac did not show that the drawings were “patents” or “printed publications” as defined by 35 U.S.C. § 311(b, but the PTAB denied the motion, noting that it only considered the design drawings for determining the knowledge of those skilled in the art.

B/E requested rehearing on the PTAB’s decision regarding the design drawings and the Board’s reliance on “common sense” in finding obviousness. The Board denied B/E’s request and B/E appealed to the CAFC.

CAFC Review of Obviousness

Noting that there was no dispute regarding the “first recess” limitation, the CAFC explained that the only limitation at issue was the “second recess limitation.” The CAFC considered both lines of reasoning considered by the PTAB in making its obviousness determination. First, the CAFC considered the PTAB’s conclusion that creating a recess in a wall to receive a seat support was an “obvious solution to a known problem”. The CAFC reasoned that the “second recess” was a predictable result or solution because a skilled artisan “would have applied a variation of the first recess and would have seen the benefit of doing so.” Thus, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s conclusion that the challenged claims would have been obvious because the addition of a second recess was nothing more than a predictable application of a known technology.

The CAFC also considered and affirmed the PTAB’s second reason for concluding that the challenged claims would be obvious, i.e. that it would have been a “matter of common sense” to include a second recess. Citing KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., the CAFC noted that common sense is critical in determining obviousness and “’rules that deny factfinders recourse to common sense’ are inconsistent with our case law.”

The Court compared the present facts to the facts of Perfect Web Techs, Inc. v. InfoUSA, Inc., wherein the CAFC affirmed a district court’s use of common sense for a teaching of a claim limitation. The CAFC noted that in Perfect Web the “technology was simple”, the limitation supplied by common sense “’merely involve[ed] repeating earlier steps’ until success [was] achieved,” and the district court clearly explained its reasoning. Explaining that the present case was similar to Perfect Web, the CAFC noted that the subject matter of the asserted patents was simple, the “missing claim limitation (the “second recess”) involv[ed] repetition of an existing element (the “first recess”) until success [was] achieved, and the PTAB’s “invocation of common sense was properly accompanied by reasoned analysis and evidentiary support.” Thus, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s conclusion of obviousness based on the reasoning that “a skilled artisan would have used common sense to incorporate a second recess in the Admitted Prior Art/Betts combination.”

Design Drawings

With respect to B/E’s assertion that the PTAB violated Section 311(b) by relying on design drawings that were neither patents nor printed publications, the CAFC explained that the PTAB did not rely on the design drawings in either of its two reasons for finding the challenged claims obvious. Thus, the CAFC concluded that substantial evidence supported the Board’s determination of obviousness independent of the design drawings and the CAFC did not reach the issue of whether the design drawings were considered in violation of Section 311(b).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Benny

July 4, 2020 03:55 amA competent patent examiner would have rejected the claim on the same grounds of prior art and common sense. The fact that this patent got to the PTAB is a reflection on the failing of the USPTO.

MaxDrei

July 1, 2020 11:31 amNever mind what the skilled person “could” have done. Did either party to the litigation adduce any evidence from technical experts, concerning what the skilled person “would” have done?

And if so, what sort of reception did it get from the court?

And in that context, what difference does it make, to the calculation whether to adduce such evidence, whether the proceedings begin at the District Court or at the USPTO. I mean, is not a District Court more receptive to such evidence than the PTO?