“Does 9.13% of PTAB trials qualify as rarely? Most would probably find that to be more often than rarely, and a concerning number that requires further investigation to determine the specific reason as to why more than three APJs were assigned.”

In Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8, of our Constitution, the founders were relatively specific. The founders give Congress power to secure “the exclusive Right” to “Authors and Inventors” in the “Writings and Discoveries”. Congress is given specific direction on how to do it (i.e., “for Limited Times”), and why it should be done (i.e., “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts”).

In Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8, of our Constitution, the founders were relatively specific. The founders give Congress power to secure “the exclusive Right” to “Authors and Inventors” in the “Writings and Discoveries”. Congress is given specific direction on how to do it (i.e., “for Limited Times”), and why it should be done (i.e., “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts”).

Unfortunately, the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) of 2011 dramatically changed how the Executive branch implements the Constitutional prerogative. The AIA transferred power constitutionally allocated to the judicial branch to the executive branch – specifically, to Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) in the USPTO.

In the process of implementing the Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB) on which the APJs sit, judicial independence, judicial ethics, rules of evidence, and other protections commonly afforded rights holders in disputes adjudicated by the federal judiciary were sacrificed in the name of expediency.

AIA is Ex Post Facto Law

Unbelievably, in 2011, Congress made the AIA retroactive and applicable to all patents still in force, which means retroactive application of the law dating back at least 20 years. The bargain struck between patent owners and the government is often described as a quid pro quo; rights in exchange for information. But the ‘ex post facto’ nature of the AIA and the ease with which patent claims can be challenged without ever being afforded a presumption of validity was not a part of the bargain. On its face this makes the AIA fundamentally unfair, if not unconstitutional.

Over the last nine years, since 2011, 84% of patents reviewed by the PTAB have been and ‘effectively’ invalidated. The resulting carnage has been cataclysmic. The PTAB has presided over a swath of IP destruction that spans more than a generation of innovation.

Finally, after eight years of the AIA, in “Arthrex Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., The Federal Circuit ruled that the APJs were ‘principal officers’ under the Appointments Clause, and that the APJ appointment provisions of the AIA creating the PTAB were unconstitutional because the APJs were not appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, as is required for ‘principal officers.’” [National Law Review]

Unfortunately, the Federal Circuit’s remedy was not to invalidate or nullify the decisions made by these unconstitutionally appointed APJs. Instead, the Federal Circuit rewrote the AIA to save the statute from unconstitutional infirmity, ordering the APJs to become employees at will and removable without cause by the Director of the USPTO. By rewriting the statute and turning APJs into employees at will, the Federal Circuit changed the proper characterization of these APJs from principal officers to inferior officers, without appointment by the President and confirmation by the Senate. This somehow retroactively made their past decisions constitutional.

Judicial Independence and Panel Stacking

There is a rule that discourages dissent within PTAB panels and requires permission from a superior prior to dissenting. The existence of this policy was confirmed in response to a FOIA request. Indeed, dissents and concurring opinions are not desired by PTAB supervisors because some APJs have been known to abuse dissents and concurrences in order to achieve production goals— APJs have a production quota in the same way that examiners have a production quota. But for APJs at PTAB they must justify to the Vice Chief Judge why a dissent or concurring opinion should count toward production goals, otherwise the work performed does not count. In other words, without permission of the Vice Chief Judge a dissent or concurrence by an APJ is done on the personal time of the APJ. It is no wonder there are so few dissents and that when there is a dissent it often seems, anecdotally, that it is one where the author believes the patent claims should have been found to be not patentable.

While the Office may have some justifiable interest in ensuring APJs do their fair share of productive work, perhaps a better approach would be to appoint judges who take the job more seriously and don’t game the system.

The judicial independence of the PTAB is also called into question by a practice known as panel stacking, which occurs when the Office appoints more judges to a panel than the standard three members. In an oral argument before the Federal Circuit in 2015, USPTO attorneys admitted that panel stacking occurs in order to achieve certain outcomes in cases.

The case where this nearly unbelievable admission was made during oral argument was Yissum Research Development Co. v. Sony Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2015). The pertinent part of the oral argument, which 717 has conveniently provided here, reads as follows:

USPTO: And, there’s really only one outlier decision, the SkyHawke decision, and there are over twenty decisions involving joinder where the –

Judge Taranto: And, anytime there has been a seeming other-outlier you’ve engaged the power to reconfigure the panel so as to get the result you want?

USPTO: Yes, your Honor.

Judge Taranto: And, you don’t see a problem with that?

USPTO: Your Honor, the Director is trying to ensure that her policy position is being enforced by the panels.

Judge Taranto: The Director is not given adjudicatory authority, right, under § 6 of the statute that gives it to the Board?

USPTO: Right. To clarify, the Director is a member of the Board. But, your Honor is correct –

Judge Taranto: But after the panel is chosen, I’m not sure I see the authority there to engage in case specific re-adjudication from the Director after the panel has been selected.

USPTO: That’s correct, once the panel has been set, it has the adjudicatory authority and the –

Judge Taranto: Until, in your view, it’s reset by adding a few members who will come out the other way?

USPTO: That’s correct, your Honor. We believe that’s what Alappat holds.

Alappat holds no such thing. Alappat dealt with a patent applicant seeking a patent where it would be reasonable for the Director (then Commissioner) to be setting Office policy. The PTAB is adjudicating winners and losers after a patent has already issued and is presumably, or at least statutorily, supposed to be presumed valid.

Nevertheless, expanded panels, or panel stacking as it came to be known, was explained by the Office to happen in only a relatively few cases. So, what is the big deal?

Panel makeup did come up in the Oil States oral hearing when Chief Justice Roberts asked: “Does it comport to due process to change the composition of the adjudicatory body halfway through the proceeding?

Department of Justice Deputy Solicitor General, Malcolm Stewart, limited his response carefully, replying: “This has been done on three occasions. It’s been done at the institution stage.” [Oil States Oral Hearing [Nov 2017]

Chief Justice Roberts’ question, however, was potentially illuminating.

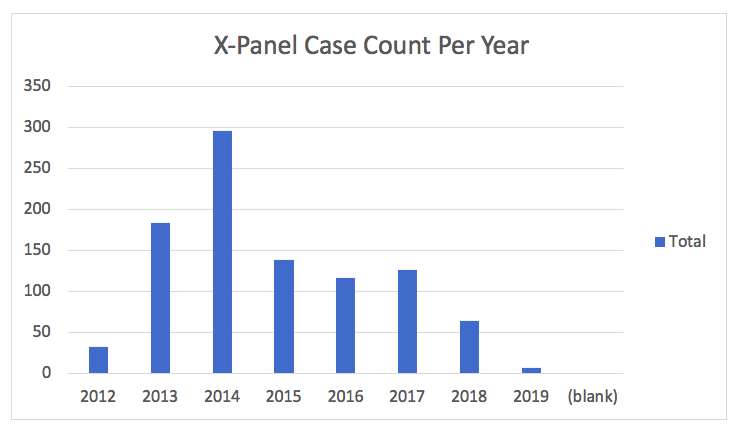

To check the veracity of these statements, an extensive independent count was made of the number of APJs per case at the PTAB, as per data made available from Docket Navigator for 10,521 cases (circa Sept 2011 through Aug 2019). It was found that 9.13% (961 / 10,521) of PTAB trials had more than three APJs on the panel.

Does 9.13% of PTAB trials qualify as rarely? Most would probably find that to be more often than rarely, and a concerning number that requires further investigation to determine the specific reason as to why more than three APJs were assigned.

Perhaps there is a legitimate explanation, such as training new APJs, but the PTAB has operated in such a secretive manner historically that when such irregularities arise, such as more than three APJs being assigned, or panels changing in the middle of a case, questions arise. The PTAB would do well to answer these questions as they arise and not let imaginations run wild, because when a process that is supposed to be open since an issued patent is at stake is conducted with such secretive ways by those who will adjudicate the proceedings, it feels rotten.

To be fair, the number of expanded panels peaked in 2014 and then remained largely constant throughout the second Obama term. They have been on the decline during the Trump Administration, although data for 2018 and 2019 is partial, as cases are still in process.

The Arthrex Factor

The history of the PTAB, although brief, has been a sordid mess. If, in Arthrex, the Supreme Court considers the way the PTAB is actually run in practice, the question of whether APJs are principal officers or inferior officers is a much more difficult decision. On paper, the Federal Circuit decision in Arthrex seems perfectly logical, although the remedy is bizarre and constitutionally questionable— to say the least. In practice, however, PTAB superiors have historically micromanaged the PTAB in ways that demonstrate the absence of judicial independence.

What an irony it would be for the Supreme Court to decide that the Federal Circuit was wrong in Arthrex because those on the PTAB are merely employees who have no judicial independence and are not entitled to really be called judges. Chief Justice Roberts already hinted at that during oral argument in Oil States when he said that the chief judge of the PTAB was an “executive employee”. “When we say judge,” Roberts quipped, “we usually mean something else.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

14 comments so far.

Paul Hayes

August 9, 2020 06:20 pmAnon,

re: 11 & 12.

Agreement here.

ipguy

August 5, 2020 05:46 pm@ AAA JJ re 10

“I cannot understand why any applicant would select the US as the ISA.”

It can come down to cost. For small entity clients, it costs an extra $910 to use the EPO instead of the US as the ISA. The savings means a big difference to cost-conscious small entity clients who know that they may get a dead-weight Examiner who milks the examination for as many RCEs as they possibly can. South Korea is slightly cheaper than the US but their searches, in my opinion, are even worse than US searches. I use the EPO as the ISA when my client is a large entity.

Anon

August 5, 2020 03:23 pmTFCFM,

As usual, your version of reality is missing quite a few rather important facts (such as reexamination having a required safety valve back to a proper Article III forum).

Your view is anti-patent.

Why am I not surprised?

Anon

August 5, 2020 03:18 pm“but should those rights be deemed waived?”

THAT is a very good question.

I hint at my view with the comment of ‘(for some, unforeseeable),’ and have the general view that ANY item of Constitutional import must be waived ONLY by an explicit and affirmative action.

I have a much bigger problem with the view of the court that they can rectify a statutory issue dealing with a (possible) Constitutional defect with a type of ‘line item veto’ and change the underlying legislation with an excuse of, “Well, we THINK that that is what Congress would have wanted.”

The Judicial Branch is NOT the Legislative Branch.

Common Law is NOT meant to carry the power that the courts have grown accustomed to wielding.

This action is clearly ultra vires.

AAA JJ

August 5, 2020 01:25 pm” Now the searches are outsourced (to Cardinal IP?) and (i my view) nearly worthless and off-point. ”

PCT searches for the US as the ISA are done by contractors. (I believe it’s Cardinal, but there may be another contractor or two that also does them.) I don’t recommend to clients that they use the US as the ISA because, as you note, the search results are essentially worthless. And as the regular examining corps will examine any 371 or by-pass continuation they feel free to ignore the ISR and IPRP and most often do. I cannot understand why any applicant would select the US as the ISA.

ipguy

August 5, 2020 12:04 pm@AAA JJ re 7

“affirm at all costs” mindset

That seems consistent with things I’ve seen. It matches the “reject at all costs” seen in the PCT searches where the US is the searching authority. When I was an Examiner, we did the PCT search ourselves, sent out the search report for the PCT, and then examined the US counterpart using the art found during the search. Now the searches are outsourced (to Cardinal IP?) and (i my view) nearly worthless and off-point. (submit arguments against the reference and you’ll get back an even more entrenched updated search/written opinion).

TFCFM

August 5, 2020 10:15 amThis statement:

PH&GQ: “The AIA transferred power constitutionally allocated to the judicial branch to the executive branch – specifically, to Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) in the USPTO.”

seems to me unsupportable (and unsupported).

The Constitution has never been interpreted to mean that the Patent Office cannot reconsider its decision to grant a patent in light of new evidence that the decision-to-grant was erroneous. Nearly 40 years ago, the question was settled for reexamination proceedings, for example.

The statement also appears to fly directly into the face of the US Supreme Court’s Oil States Energy Services decision a few years back — expressly holding an AIA post-grant procedure not-violative of the Constitution, and doing so expressly over arguments that the procedure failed to comply with Article III.

When neither the Constitution itself nor the Supreme Court’s constitutionality-assessment of a statute support one’s argument that the statute is unconstitutional, one might be well advised to consider the futility of continuing to rehash the argument.

AAA JJ

August 5, 2020 10:02 amHad a partner at one of our provider firms speak to us. He was a former APJ. He told us the APJ’s have an “affirm at all costs” mindset. Wasn’t a surprise to me.

Paul V. Hayes

August 5, 2020 08:52 amAnon,

re: 5

You are of course correct, that’s the argument made by CAFC, but should those rights be deemed waived? …..in light of the injustice that followed and what would be the point of raising a constitutional issue at PTAB.

How many small inventors can afford a trip to District Court, then a trip to PTAB, then a trip to CAFC when 50% of the appeals to CAFC get rule 36’d and only half of those that are heard are helpful to the appellant.

Anon

August 4, 2020 06:36 pmSmall nit with the article:

“This somehow retroactively made their past decisions constitutional.”

No.

Explicitly, it only makes decisions AFTER the case invoking the remedy to be “Constitutional.”

ALL cases prior remain “Unconstitutional,” with the major caveat being that if you did not persevere in (for some, unforeseeable) arguments as to your rights, those rights are merely deemed waived.

ipguy

August 4, 2020 04:39 pmI’ve been looking for pre-AIA passage articles where, as you put it, the PTAB is being sold as an unbiased reviewing body. Heck, I’d love to find one where the USPTO says the BPAI was an unbiased reviewing body. With regard to the PTAB, I’m only able to speak to experiences on the ex parte side.

Anon

August 4, 2020 03:29 pmipguy,

The simple answer to your point of

“don’t know any practitioners who consider the BPAI/PTAB to be an unbiased reviewing body on the ex parte side”

is because that was exactly how the PTAB was sold in the AIA for post grant operations.

ipguy

August 4, 2020 02:58 pmThat was an informative and enjoyable read. In my experience, the PTAB (and its predecessor, the BPAI) have never been anything more than instruments of USPTO policy. I don’t know any practitioners who consider the BPAI/PTAB to be an unbiased reviewing body on the ex parte side. Even when the Examiner is reversed, the PTAB panel seems to, more often than not, come up with new grounds of rejections, including section 101.

Is there any case law where a Federal court held that a particular USPTO policy was an unconstitutional end-run around a statutory requirement?

AAA JJ

August 4, 2020 02:48 pmTrying to rely on Alappat proves what anybody who deals with the PTO already knows: they have no ethics or shame/