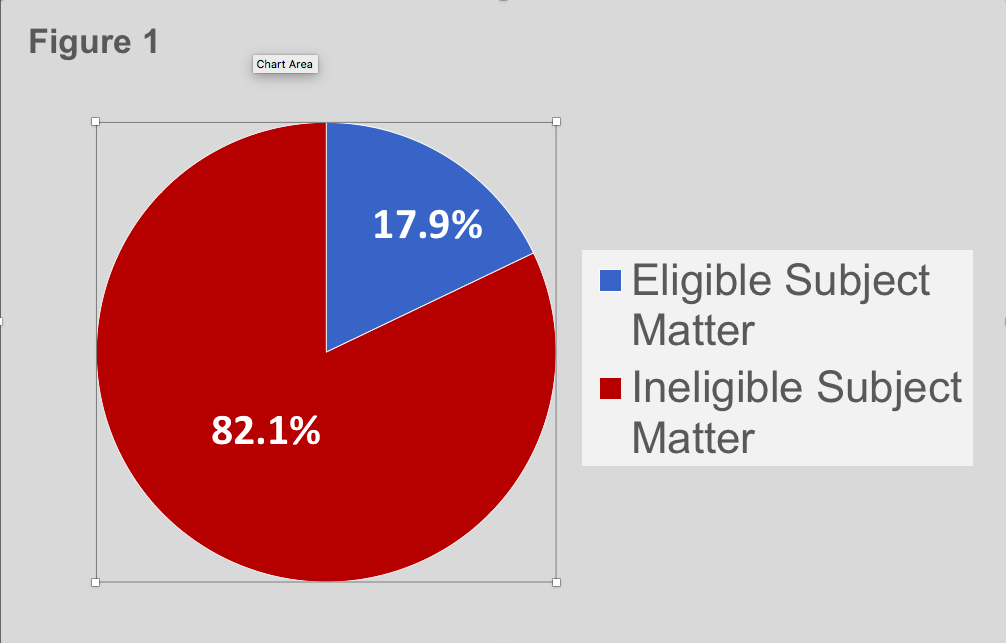

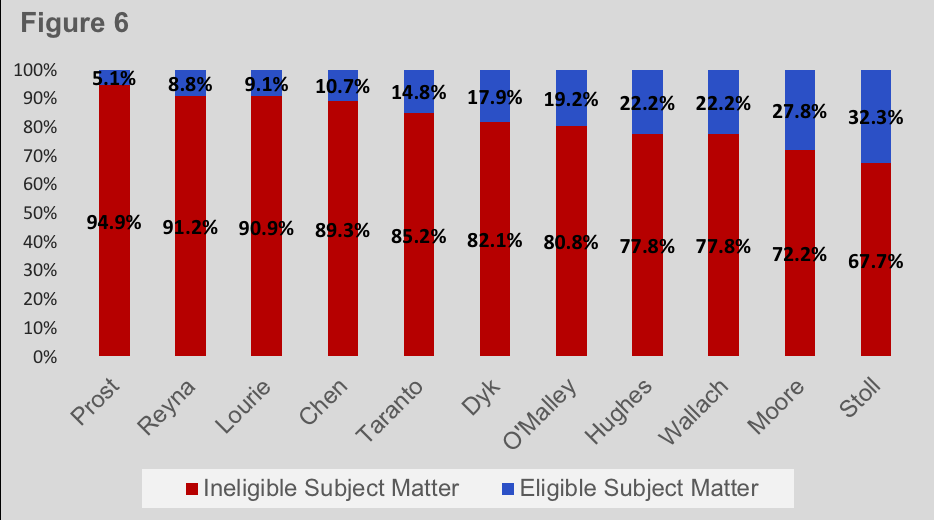

“Since June 2014, Federal Circuit panels invalidated patent claims based on Section 101 at a high rate. At Step 1, these panels found the claims ‘directed to’ ineligible subject matter 82.1% of the time, leaving just 17.9% where the claims were found to be directed to eligible subject matter.”

Everyone agrees that the 2014 Alice v. CLS Bank decision dramatically changed courts’ approach to patent eligibility analyses under Section 101. Six years later, the Federal Circuit has issued enough opinions on the issue to allow for quantitative analysis to aid patent practitioners before that venue.

Methodology

We gathered our data set by reviewing every Federal Circuit decision addressing Section 101 since the Supreme Court’s Alice ruling. We tracked the judges’ individual Step 1 and Step 2 votes in each case and the ultimate panel decisions. We also recorded the opinions’ authors and the authors of any dissents, and which decisions were per curiam.

Numerous cases involved independent analyses of different groups of claims. In those circumstances, we coded the votes on each claim or group separately. As a result, some cases ended up with multiple votes by a single judge being recorded on both Step 1 and Step 2.

The Federal Circuit as a Whole

Since June 2014, Federal Circuit panels invalidated patent claims based on Section 101 at a high rate. At Step 1, these panels found the claims “directed to” ineligible subject matter 82.1% of the time, leaving just 17.9% where the claims were found to be directed to eligible subject matter.

Individual voting skewed even further against eligibility. Individual judges voted for Step 1 ineligibility at a rate of 83.9% and for eligibility only 16.1% of the time. The difference shows that patent-eligible opinions were more likely to draw dissents than decisions holding the claims directed to ineligible subject matter.

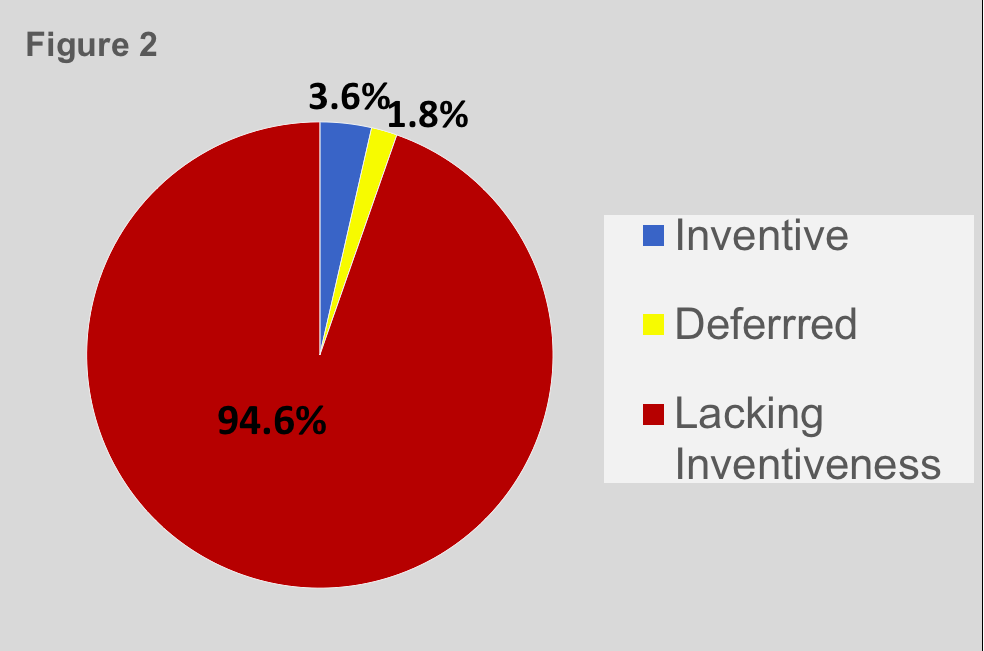

Analysis of Step 2 decisions presents an even more sobering picture for patent owners. Only 3.6% of decisions found an inventive concept to preserve validity. Two cases, or 1.8%, deferred a determination for further factual developments. And 94.6% of the decisions found no inventive concept.

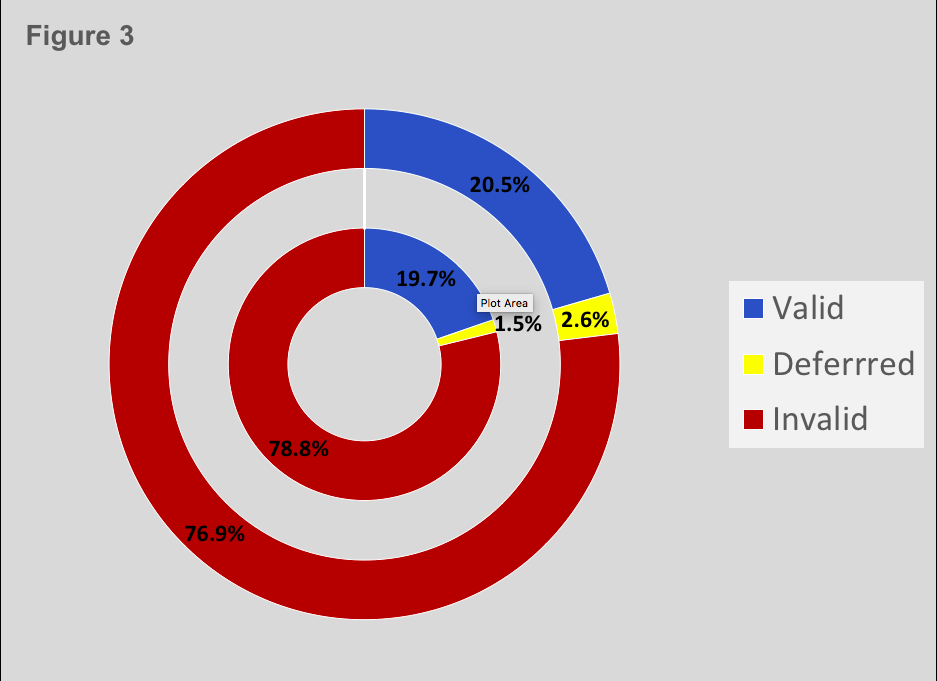

The combined result of the Federal Circuit’s Step 1 and 2 analyses is an overall invalidation rate of 78.8%, a Step 2 deferral rate of 1.5%, and a validation rate of 19.7%. Of these decisions, 20 were per curiam opinions of invalidity, but the Federal Circuit has not issued any per curiam opinions of patent eligibility. The resulting message is that Section 101 invalidity is much more likely to be a straightforward, uncontroversial outcome than validity.

The data undermine the most obvious explanation for these high rates: that they reflect review of an inordinate number of patents already found invalid by a district court. District court invalidity determinations, particularly those at the pleading stage, reach the Federal Circuit more quickly than validity determinations, which allow the case to proceed. Were that the reason, those invalidation rates would drop over time as the patents district courts found valid reached the Federal Circuit. Yet, considering cases only from the 2018 Berkheimer decision and beyond shows almost no change in these rates, with what little change there is attributable to the introduction of the deferral outcome, not to increased validity holdings:

The degree to which the Federal Circuit has favored Section 101 invalidity over validity, therefore, should be surprising to both patentees and alleged infringers. Most of these cases arise from litigation, where the presumption of validity applies, requiring proof of invalidity by clear and convincing evidence. In addition, one would expect that only patent owners who believed they had a reasonable chance of success on this issue would bear the costs of a Federal Circuit appeal; those with obviously invalid claims would be unlikely to take it that far.

The other lesson from this analysis is that patent owners seeking success at the Federal Circuit should focus on winning at Step 1. Even with the addition of validity-preserving deferral as a possible Step 2 outcome, chances of success at that stage are extremely slim.

Individual Judges

Many commentators, and even some Federal Circuit judges, have criticized the Alice two-step legal framework as ambiguous and unworkable. If these criticisms are right, it risks making which judges sit on a panel determinative of the outcome, rather than the merits of the patent claims at issue. Analyzing the judges’ written decisions and votes is a way to test whether this concern is legitimate.

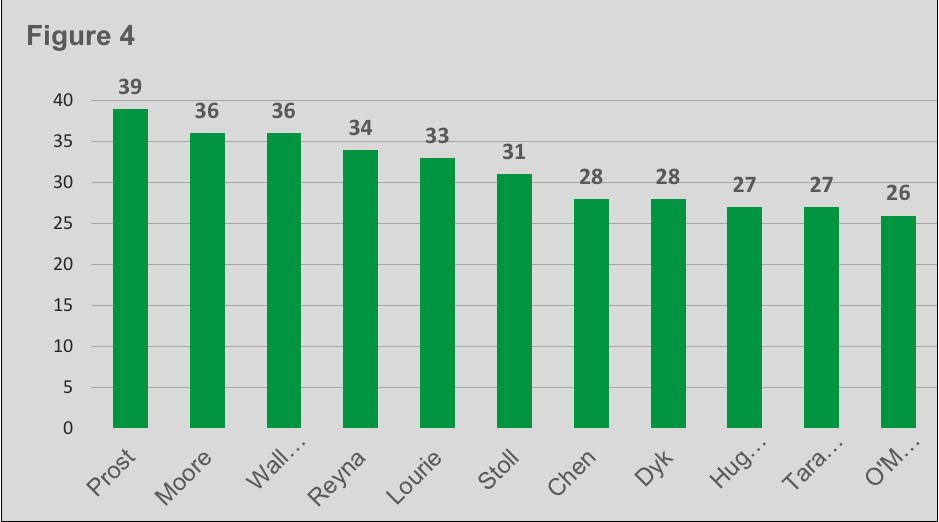

Of those judges who have participated in at least 20 cases addressing Section 101 eligibility, Chief Judge Prost has sat for the most (39), followed closely by Judge Moore (36).

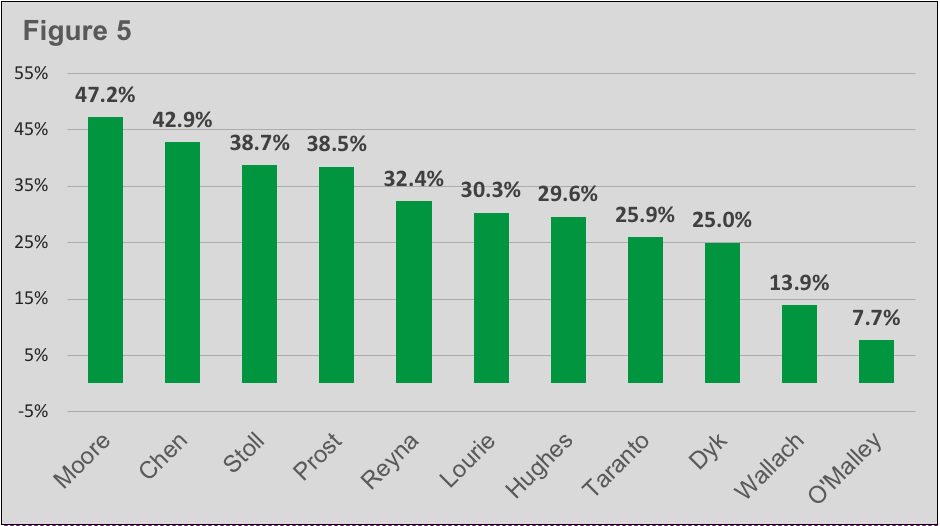

Which panel judge authors an opinion depends on the judge’s seniority and interest in writing on the issues in that case. The two judges who have issued the most decisions (of those issuing five or more) are Judges Moore (17) and Prost (15). Judge Moore authors the panel decision in 47.2% of her Section 101 cases, and Judge Chen is close behind at 42.9%. Judges Prost and Stoll also author opinions in these cases more frequently.

Because findings of Step 2 inventive concept are so rare that little distinguishes the judges, we limited our analysis of their individual voting rates to the issue of Step 1 patentable subject matter.

It is noteworthy that Chief Judge Prost, who has sat on the most Section 101 panels and issued the second most opinions, is also the most likely to find patent claims directed to ineligible subject matter. She finds just 1 in 20 patent claims directed to subject matter the USPTO should have considered for patentability. Judge Reyna is not far behind.

Judges Moore and Stoll serve as the Federal Circuit’s other pole. Of those two, Judge Moore appears to have the greater impact, having written the most opinions (17) on the Circuit. And those opinions result in Step 1 ineligibility at a lower rate (64.7%) than her voting (72.2%). Judge Stoll has votes for ineligibility less frequently (67.7%), and 50% of her 12 written opinions found the subject matter patent eligible.

Use the Data to Find Your Focus

The Federal Circuit is indeed a daunting Section 101 venue for patent owners. Those facing appeal need to concentrate on Step 1 of the Alice framework, as that is where almost all appeals are won or lost. And the reported data on voting patterns may help lawyers to focus on the judges who are most likely to be persuaded at oral argument.

Join IPWatchdog for Virtual CON2020 later today, beginning at 12:00PM, where Retired Federal Circuit Chief Judge Paul Michel and other panelists will address whether the Federal Circuit remains relevant considering its confusion around subject matter eligibility, among other topics. Register here to attend for free.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

7 comments so far.

Curious

September 3, 2020 12:36 pmJudge Newman has sat on only 15 panels dealing with the issue, and our cutoff was at 20.”

There are 12 active judges at the Federal Circuit. Stoll was the most recent, and she was appointed in 2015. As such, the active slate of judges has been essentially unchanged over the last 5 years. When the “cutoff” encompasses 11 of them, I really don’t see a need to exclude the 12th. I would have no problem excluding all of the Senior Status judges, but Newman is still an active judge.

I haven’t seen the most recent numbers, but from what I’ve seen in the past, Newman isn’t an outlier. Honestly, I see no good reason to exclude her.

Pro Say

September 2, 2020 04:19 pmThanks for the nice analysis guys.

The obvious, excruciating bottom line is this:

The CAFC is . . . the graveyard of innovation.

While SCOTUS refuses to put a stop to it . . . and Congress twiddles its fingers, the graveyard grows ever larger.

Anon

September 2, 2020 02:57 pmInteresting – why a cut-off with a limited number of judges?

It’s not there is a ‘statistical significance’ factor involved in the aspect of a judge making a decision (on the merits of what is necessarily a case by case basis).

Just because one can apply “quant” does not mean that the result is actually meaningful.

Eileen McDermott

September 2, 2020 12:45 pmFrom the author: “Our data does not account for Rule 36 affirmances.

Judge Newman has sat on only 15 panels dealing with the issue, and our cutoff was at 20.”

Curious

September 2, 2020 11:11 amQuestion for the authors? Does this account for Rule 36 affirmances? I suspect not as there are many times when a decision reaches the CAFC in which the claims were deemed unpatentable for several reasons and the CAFC need only pick one to affirm under Rule 36. That being said, there are still a good number of cases that reach the Federal Circuit that are solely on 101 issues (e.g., 12b6 motions, motions for summary judgment, among others).

I suspect that if those cases were included in the data, the results would look even more bleak. I don’t recall the latest statistics, by a very large portion of cases are disposed of using Rule 36.

The simple fact is that the CAFC, at best, is extremely hostile towards patents. At its worst, the current CAFC is probably the worst thing that has happened to patent law in the last few decades. Granted, Congress gave us the AIA and the Supreme Court gave us decisions like KSR, Alice, and Oil States, Bush gave us Dudas, and Obama gave us Lee. However, the CAFC took a fairly narrow expansion of Bilski (in Alice) and completely blew it out of proportion — so much so that any invention directed to any technology (even if it has been around for nearly a century like propeller shaft assembles) can be deemed “patent ineligible.”

BTW — what happened to Judge Newman? Your charts omit her and you provide no explanation as to why.

Anon

September 2, 2020 08:11 amBy the way, this is of a similar vein (albeit different in not so subtle ways) from the misguided views on ‘looking back’ on 101 decisions that was done awhile ago over at PatentDocs (which I anticipate MaxDrie ‘hawking’ on this thread).There, the lack of accounting for a hindsight treatment tied to a true Rule of Law was extremely problematic. Here, the state of the law as it actually exists is given short shrift as if ‘quant’ can be a proper guide is simply untenable.

Anon

September 2, 2020 08:07 amA not so minor nit with the attempt to be a ‘quant’ here is that the plain fact of the matter is that the CAFC (through the USSC) has a Gordian Knot of 101 jurisprudence.

I do NOT think that the ‘quant’ approach appreciates that critical factor. You cannot be a ‘quant’ when the basic notion of having a deterministic result is simply not there.