“If accused infringers need not come forward with any evidence—if bald assertion is enough—they will have incentive to assert indiscriminately that products were not properly marked. At no cost to themselves, they could inflict on patentees the arduous and costly task of proving that each of those products either does not practice the invention or is properly marked.” – Packet Intelligence petition for rehearing

Packet Intelligence, LLC has filed a combined request for rehearing and rehearing en banc with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, asking the Court to review a July 2020 panel decision relating to its interpretation of the patent marking statute, 35 U.S.C. §287(a). In that case, Packet Intelligence, LLC v. NetScout Systems, Inc., the panel reversed a pre-suit damages award for Packet Intelligence on the ground that NetScout was entitled to judgment as a matter of law that it was not liable for pre-suit damages based on intervening case law in Arctic Cat Inc. v. Bombardier Recreational Prods. Inc.

Packet Intelligence, LLC has filed a combined request for rehearing and rehearing en banc with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, asking the Court to review a July 2020 panel decision relating to its interpretation of the patent marking statute, 35 U.S.C. §287(a). In that case, Packet Intelligence, LLC v. NetScout Systems, Inc., the panel reversed a pre-suit damages award for Packet Intelligence on the ground that NetScout was entitled to judgment as a matter of law that it was not liable for pre-suit damages based on intervening case law in Arctic Cat Inc. v. Bombardier Recreational Prods. Inc.

Shifting Burden

In Arctic Cat, the CAFC held that an alleged infringer “‘has an initial burden of production’ to ‘articulate the products it believes are unmarked ‘patented articles,’ after which ‘the patentee bears the burden to prove the products identified do not practice the patented invention.’”

In its July 2020 decision, the Court noted that the district court’s jury instructions appeared to place the burden fully on NetScout, but pursuant to Arctic Cat, “NetScout bore the preliminary burden of identifying unmarked products that it believed practice” the patent at issue, and Packet Intelligence then bore the burden of proving that its licensee’s product (MeterFlow) did not practice at least one claim of the patent. NetScout had met its burden under this standard, said the CAFC, but Packet Intelligence “had not presented sufficient evidence to carry its burden to prove MeterFlow did not practice the patent.”

The petition for rehearing argues that: 1) remand, rather than reversal, is warranted to allow Packet Intelligence a chance to prove its case under the intervening Arctic Cat standard; 2) accused infringers should not be able t satisfy the “burden of production” element under Arctic Cat by merely asserting that an unmarked product practices an invention; rather, the accused infringer must provide evidence, which NetScout did not do; and 3) the CAFC erroneously extended the patent marking statute requirements to licensees. “That defies the statute’s plain meaning, Supreme Court precedent, and sound policy,” says the petition.

Remand, Not Reversal

Since the parties tried the case on the understanding that NetScout bore the full burden of compliance with the marking statute, remand is proper, as in the Arctic Cat case itself. There, the CAFC concluded that “reversal would be improper,” because the patentee “was not on notice regarding its burden, and in fact labored under the assumption that [the accused infringer] had the burden of proof.” Packet Intelligence was similarly “not on notice regarding its burden” and thus reversal was improper.

Evidence, Not Assertion

As to the minimum standard for the “burden of production” under Arctic Cat, the petition argues that the CAFC’s conclusion here that accused infringers must do nothing more than assert that certain unmarked products practice the invention “defies Arctic Cat and general principles.” The Arctic Cat case described the showing the accused infringer must make as a “burden of production” at least seven times, a term which has a “well-settled meaning” of a “burden of going forward with evidence,” as articulated in Dynamic Drinkware, LLC v. Nat’l Graphics, Inc., 800 F.3d 1375, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2015). The petition warns that the CAFC’s flouting of this standard could have broad implications:

If accused infringers need not come forward with any evidence—if bald assertion is enough—they will have incentive to assert indiscriminately that products were not properly marked. At no cost to themselves, they could inflict on patentees the arduous and costly task of proving that each of those products either does not practice the invention or is properly marked. The gamesmanship potential is obvious: Accused infringers could dramatically increase patentees’ litigation expenses—and discourage them from asserting their rights in the first place—by mere incantation of supposed marking violations.

Licensees Are Not Agents

The petition also urges the Court to go en banc to clarify that Section 287 does not require marking by licensees, but only by patentees and their agents. The CAFC panel misconstrued the plain meaning of the statute in holding that Packet Intelligence’s licensee was required to mark patented articles, says the petition:

The statute requires marking by patentees and those acting “for or under them”…. [F]or a person to make and sell “for or under” a patentee, that person must do so “on [the patentee’s] behalf and subject to his control”—in other words, as the patentee’s agent…. A mere licensee, however, is not a patentee’s agent. Licensees do not act “for” or “under” the patentee.

While other courts, including the CAFC, have extended the marking statute to licensees in the past, the petition argues that there has been no supporting analysis offered in those cases and thus the substantive issue of licensee marking has never been litigated. The petition concludes:

It is not reasonable to demand that a patentee conduct a preemptive (and perpetual) sourcecode-level examination of all licensee products—or risk forfeiting its right to recover from infringers. That burden is particularly unreasonable with respect to small patentees who have neither the means nor the leverage to subject their licensees to that inquiry.

Many patent licenses today reflect a commendable desire to avoid such burdensome inquiries…. Under existing precedent, such licenses unwittingly compromise patentees’ ability to recover from unlicensed parties. Without any evidence, infringers can assert that a patentee’s licensees have sold unmarked articles and put the patentee to the costly task of attempting to prove otherwise—for dozens if not hundreds of products potentially covered by broad portfolio licensees. Patentees unable to bear that expense will be forced to surrender considerable relief. The result will be to discourage beneficial licensing practices—to the detriment of innovators, licensees, and consumers alike.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Vector ID:71178913

Copyright:Aquir014b

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

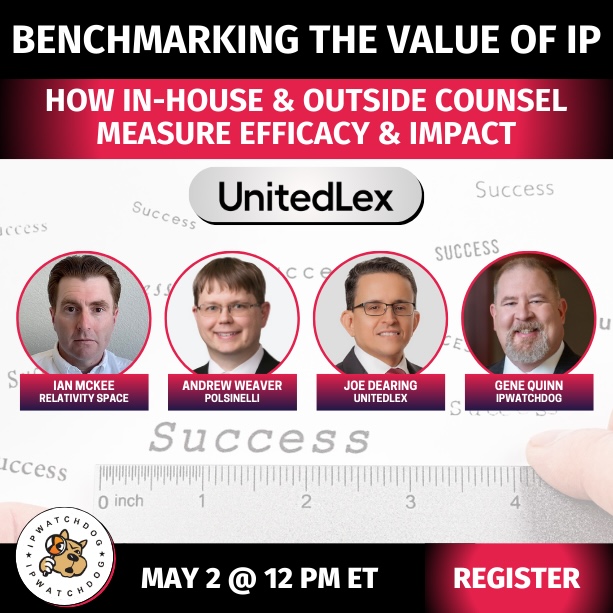

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.