“The confusion around how to answer when someone asks the going rate for a patent in part stems from the common use of “price” and “value” nearly interchangeably in day-to-day conversations.

Imagine you have found four patent families that address a specific risk to your business, and you are about to ask your boss to approve buying those patents for $2 million. Her questions might include, “What’s the going rate for patents?” Similarly, if you were working with your company’s accounting team and moving four patent families from your corporate parent to a subsidiary, the accounting department might ask, “What is the ‘fair market value’ of these patents for transfer pricing?”

Unpacking the Questions Posed: Definitions

A preliminary issue arises: what are you really being asked for? This confusion in part stems from the common use of “price” and “value” nearly interchangeably in day-to-day conversations.

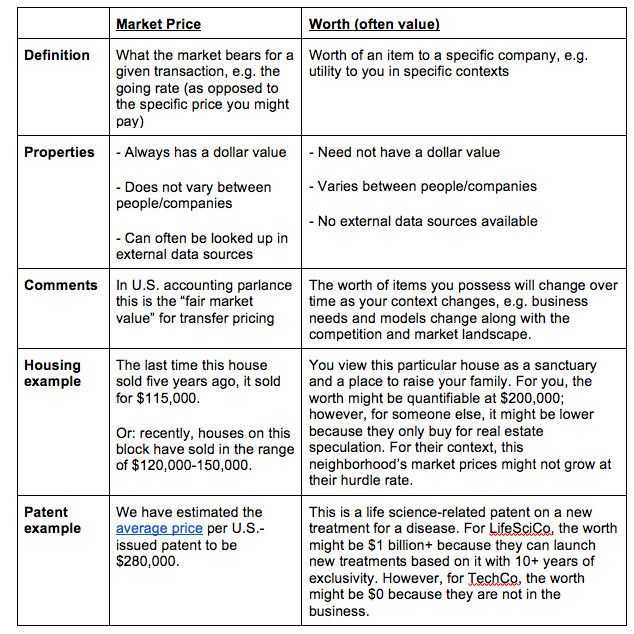

For more precision, the terms “market price” and “worth” will be used in the rest of this article as follows:

One last definition: “impact”: the worth minus the price you actually pay. If you pay $1 million for something that is worth $10 million for you, then the impact is $9 million. This is important because ultimately you should be testing and measuring the impact of your activities rather than the price paid.

Quickly Modeling Patent Market Prices

With these definitions in mind, it is clear: both your boss and the accountant from the introduction to this article are actually asking you to estimate market price. Now, the next problem arises: how can you do that in a systematic way that’s fast, simple, and data-driven?

One way to tackle this problem is to develop a tool. For such a tool to be usable, it needs to hew strongly to the K.I.S.S. principle: keep it short and simple. This necessarily means that the rich complexity in a traditional valuation approach will be skipped and the answer will be, get ready for it: wrong. However, if the result is useful, any loss of accuracy can be handled in subsequent rounds of diligence.

One model that is used incorporates three datasets heavily focused on computer hardware, software, and communications patents. The used data sets:

- Closing prices from the firm’s history ($130 million+ of closed patent purchases and sales)

- Real prices report ($2 billion+ closed deals from over 25 companies)

- Patent market data on asking prices ($36 billion+ patent assets tracked across 11,000+ packages)

Inputs to the Model

With a baseline set of data on market prices, to adhere to K.I.S.S. it is necessary to make the inputs to the model as simple as possible and settled on only three inputs:

- Number of patent families

- Deal type: private, brokered, or fixed-fee auction, and

- A deal adjustment, e.g. a catch all for non-company specific criteria for patents

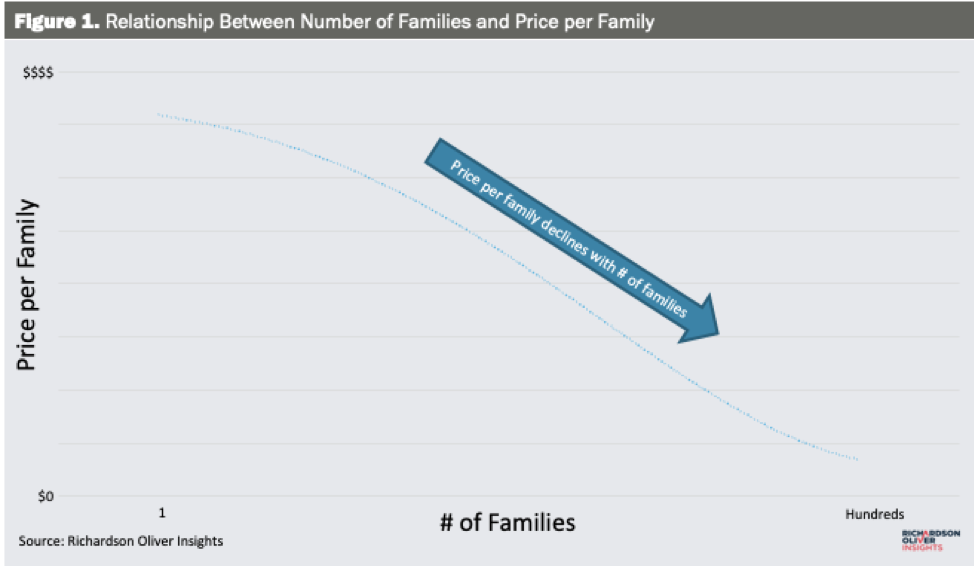

Let’s explore each of these and their rationales. Starting with the number of families. The data (see Figure 1), shows a consistent trend that the more families in a patent deal, the lower the price per family.

This is one of the most significant effects on price. It makes intuitive sense in the context of a typical transaction: if a single patent family is being transacted then all of the worth is in that patent. Adding nine more families to the same transaction does not necessarily increase the worth. In fact, the buyer might even ascribe minimal, or negative, worth to the other nine families.

The next most significant input is the deal type. There are three primary ways patents are currently transacted: privately, brokered, and via fixed-fee auctions. Each is associated with different price levels. A private deal is one where the buyer approaches a seller directly (or vice versa) to transact a specific set of assets. In contrast, brokered deals are quasi-public. The broker (or seller) is making the deal available to a larger audience of potential buyers. The line between private-and-brokered can be a fine line: some brokers start to circulate deals privately to a handful of prospects and then expand to a broader audience of buyers. Lastly, the fixed-fee auction format, which Google launched and AST has popularized, involves a quick, no-negotiation auction where sellers name their prices and get promised a quick transaction.

The model uses blended data about deals and then builds an adjustment for the deal type (see Figure 2). This approach trades precision for speed. As Figure 2 shows, private deals command a premium while fixed-fee auctions tend to sell at a discount. The brokered market lies in between.

This general pricing trend is in alignment with the experiences professionals have had based on many transactions. Lastly, an input was added to allow for adjustments (see Figure 3). The goal of this input is to allow the modeler to reflect generally accepted adjustments to market price. This should not be used to model any company-specific uses of the patent. Returning to a housing example, generally agreed upon items: square footage, number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms, finished basement, and quality of the schools could all be used. In contrast, personal preferences about the location or design of the house would not.

Returning to patents, acceptable adjustments would include: a boost for open continuations, a boost for greater internationalization, a boost for general adoption of the claimed technology, a reduction for extremely long claims, etc. In contrast, a company’s own view that technology X is important should not be used for an adjustment.

Interpreting the Results and Answering the Questions

With the model set up, let’s answer the questions from the introduction:

Scenario 1: Purchase four patent families for $2 million. Filling in the inputs you tell your boss you are purchasing these privately and they have a number of good qualities due to extensive internationalization in all of the major economies where the technology is used (e.g. “++”). The model quickly indicates that the median price is $3.25 million and the range of pricing from the 33rd-to-66th percentile is $1-to-4 million (numbers have been rounded). This answers your boss’ question about “the going rate” and helps her contextualize your proposed bid of $2 million. We recommend that you talk about the worth of the patents and the impact with her as well.

Scenario 2: Transferring four patent families between your corporate affiliates. You were asked to provide the “fair market value.” In this case, you can partner with the accounting department to get agreement to use the brokered pricing table because they want to have a better sense of how arm’s length participants might transact. The particular four families you are transferring are not internationalized outside your headquarters-region; you nonetheless choose to model at neutral given other positive factors such as a multitude of short claims. This puts a median price of $1 million and a range for the 33rd-to-66th percentile from $0.4-to-$1.25 million. The accounting department can then decide if a more detailed market comparable analysis is necessary, or if these modeled estimates can suffice.

Focus on Worth and Impact

Outside of accounting, the business focus should be on quantifying the worth of the patent to your company as well as the impact. In a follow-up article we will cover how this modeling approach can be extended to a K.I.S.S.-style model for quickly estimating worth and thus impact.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

8 comments so far.

Xtian

September 30, 2020 09:35 amAnon – I think we agree here. I refuse to acknowledge that a PAE even exits. Using this language is only an attempt at demagogy.

For example, in the pharma industry, there are many patents on compounds (genus patents) which may have failed in the clinic for one reason or another. For my example, I will use “Acme Pharma” and Start-up Pharma”. Acme Pharma is a multi-billion company with dozens of branded pharmaceuticals on the market. Acme’s compound “failed” development. Acme Pharma moves to a different compound (outside of the genus patent) because of time and resource constraints. Then, Start Up pharma sees the halt of Acme’s development, and chooses to advance a compound that falls within Acme Pharma’s genus patent because Start up Pharma thinks they can make this similar compound work. Acme Pharma wants to leverage their genus patent and licenses it to Start Up Pharma. Is Acme Pharma a PAE?

Here’s another one that no one talks about. University professor invents new compound. University’s tech transfer office patents it. University doesn’t manufacture or conduct clinical trials for any pharmaceutical. The sole intent of a University tech transfer office is to license said patent. Is University a PAE?

In both my examples, Acme and University are PAE. And so everyone is a PAE. And if everyone is a PAE, then no one is a PAE.

Anon

September 29, 2020 03:39 pmXtian,

One may agree as to general costs brought by ANY party without indulging in the “PAE” slight that Paul inserted

Was there ANY need for that?

Xtian

September 29, 2020 11:52 amAgree with Paul – actualy questions that I have received in my practice when the issue is not tax or inter-company transfer related:

1) what will it cost the company to defend against a lawsuit,

2) what will it cost the company to file an IPR on the patents;

3) what is the cost to develop around the patents for a clear non-infringing position,

4) how much is a reasonable royalty (rather than outright purchase), and

5) what will it cost the company if (even after eBay) the patent owner successfully obtains an injunction?

Anon

September 29, 2020 10:48 amMr. Morgan,

How are any incurred costs different as from those incurred due to “threats from PAEs” as opposed to “threats from non-PAEs”…?

Serious question that you should reflect upon, given that your phrasing reveals an animus that you should be aware of.

Matt D Moyers

September 29, 2020 09:58 amThe definition of mark price, in the context of a patent transaction, is more closely aligned to “Liquidation Value” rather than “Fair Market Value.” It is hard to have FMV transactions when the buyer or seller is not doing so willfully, but rather under compulsion to buy or sell.

Paul F Morgan

September 29, 2020 09:10 amEstimating Litigation costs and business interruption discovery avoidance are major factors in the many patent threats from PAEs nowadays.

Anon

September 28, 2020 01:05 pmWant another wrinkle?

Insert tax valuation fundamentals here.

Curious

September 28, 2020 10:49 amImagine you have found four patent families that address a specific risk to your business, and you are about to ask your boss to approve buying those patents for $2 million. Her questions might include, “What’s the going rate for patents?”

Wouldn’t a more real-word question be … ‘Can’t we just practice efficient infringement and ignore those patents? Everybody else does it.’