“With a way to quickly model the value of a patent purchase, we can have a higher quality discussion about the various assumptions that were made, and as we bring multiple purchases to our boss and use the same model, the decision process will be more consistent.”

Imagine you are presenting to your boss and requesting approval of a $2 million purchase of four patent families. Already savvy about market prices, she is focused on the impact of the purchase to the business. Her question: “So what are these patents worth and what will the impact be of the purchase?” Unless you have done some sort of valuation to quantify the worth of these patents for the business, you may find yourself talking vaguely about synergies or avoided costs.

Imagine you are presenting to your boss and requesting approval of a $2 million purchase of four patent families. Already savvy about market prices, she is focused on the impact of the purchase to the business. Her question: “So what are these patents worth and what will the impact be of the purchase?” Unless you have done some sort of valuation to quantify the worth of these patents for the business, you may find yourself talking vaguely about synergies or avoided costs.

This is because getting a valuation typically takes time and can be expensive. But what if there was a way to quickly model the worth of the patents to us? Undoubtedly, the answer from the model will be imprecise. However, the issue is one of usefulness. A model is designed to improve the quality of initial decisions and the discussions. Any loss of precision or accuracy can be addressed in later stages of the buying process. A model with reasonable accuracy can funnel the discussion more productively and allow greater consistency across different requests in how the decisions can be made.

Understandably, modeling worth is far more complex than market price; nonetheless, for the model to be useful, the KISS principle (keep it short and simple) is key here: the model cannot require the user to fill in dozens of details to get a result. At the same time, the model must reflect the main uses, or value streams, your company has for patents. For example, with a patent purchase one could imagine several rationales, or value streams:

- Litigation risk removal

- Cross-licensing improvement, e.g. improve your defensive counter-assertion position

- Saved design around costs, e.g. without this purchased patent the product would need to be redesigned to avoid infringement

- Product enablement, e.g. without these purchased patents the company would not launch the product

It may be possible to get multiple value streams from a single patent. For example, the same patent might remove litigation risk (your company cannot be sued) and provide cross-licensing improvement (you can use this, if threatened, to counter-assert against another company and lower the expected licensing costs). To simplify discussion, and focus on a common use case, a version of the model focused on patent purchases supporting only a single value stream at a time will be explored. Further, only litigation risk removal will be discussed in this article.

Inputs to the Model

To adhere to KISS, make the inputs to the model as simple as possible and settled on three inputs for most scenarios:

- Number of focus patent families, e.g. how many of the families are the focus of the deal

- Whether the focus patent families can be asserted against your company

- A deal adjustment, e.g. a catch all for company specific criteria for value

Starting with the number of focus patent families. Maybe the potential deal has a large number of patent families but only a handful are the focus, or the rationale, for the purchase. For example, in a deal with ten patent families, perhaps only one or two might be the focus of the deal. Stating which patent families drive the deal makes the modeling exercise more concrete.

Next, test whether the focus families could be asserted against your company, yes/no. This determines whether the modeler believes that a credible assertion of the focus patents can be made against your company. E.g. is there a reasonable fit between the claims of one focus family patents and your company’s product, yes/no. If answered no, the litigation value could be set to $0, or nearly $0. If yes, the modeling can proceed.

Next, deal adjustments should be made. This is the space for company-specific views on the patent. For example, more vs. less projected product revenue at risk, intersection with strategic aspects of the company’s product roadmaps, perceived importance of the patents, and other risk factors. A simple slider can be used as seen in Figure 1. For example, at the “–” a purchase with less strategic value would be positioned, e.g. an opportunistic pick up for a small segment of the business. At the other end of the scale, patents relating to key parts of the company’s future roadmaps might be ranked “++”.

After these generalized inputs, any specific inputs for the use case would need to be provided. In this example, we are showing a simple avoidance of litigation risk model.

The Simple Litigation Model

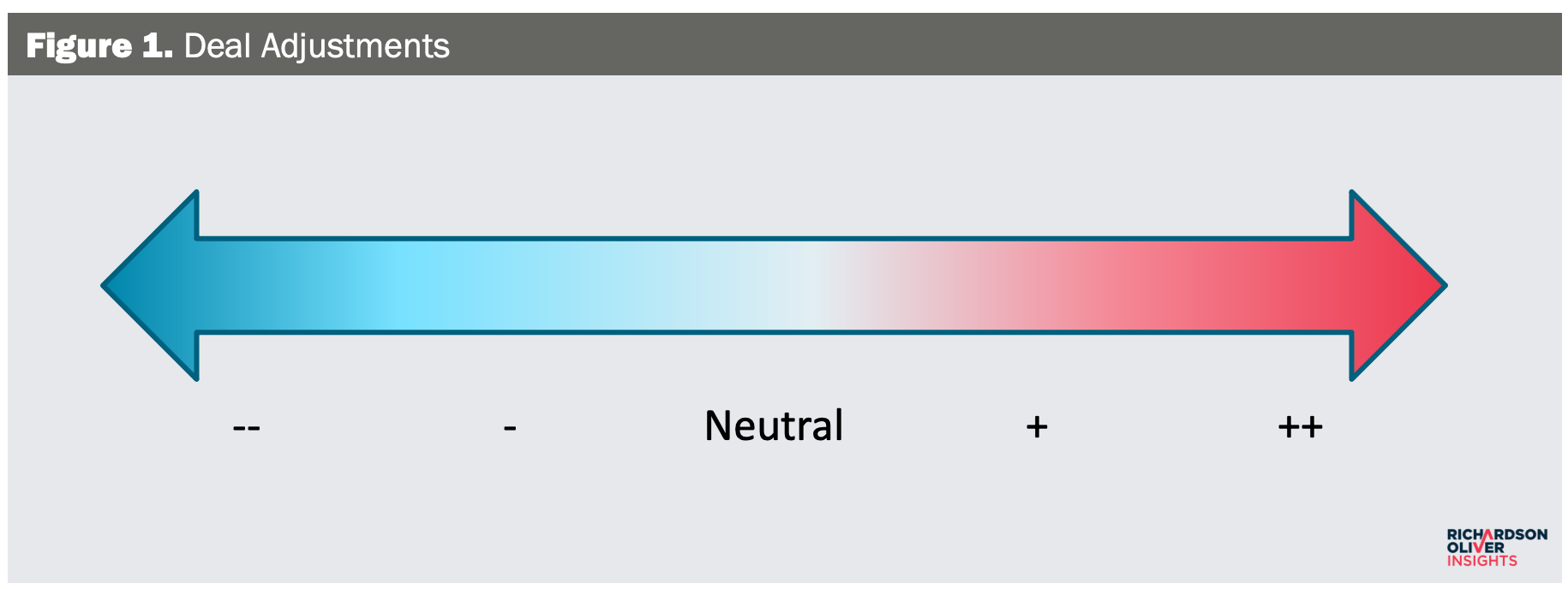

For litigation, one challenge that arises is shown in Figure 2: the distribution of expected litigation costs (including damages) is right-skewed. This means that the most frequent outcomes have nearly no cost (e.g. respond to a letter and move on); however, there are infrequent really bad outcomes ($1 billion+ damage awards). If our model used the expected costs, the effect would be to say costs are close to $0 and the model would effectively say “never buy a patent” because the worth of buying the patent vs. letting it remain available is $0. More concretely, you are asking your boss to spend $2 million and get $0 of worth. Not an easy sale. On the other hand, if sued, even if you win the litigation, in the United States you are likely to be out significant costs depending on how far the suit progressed.

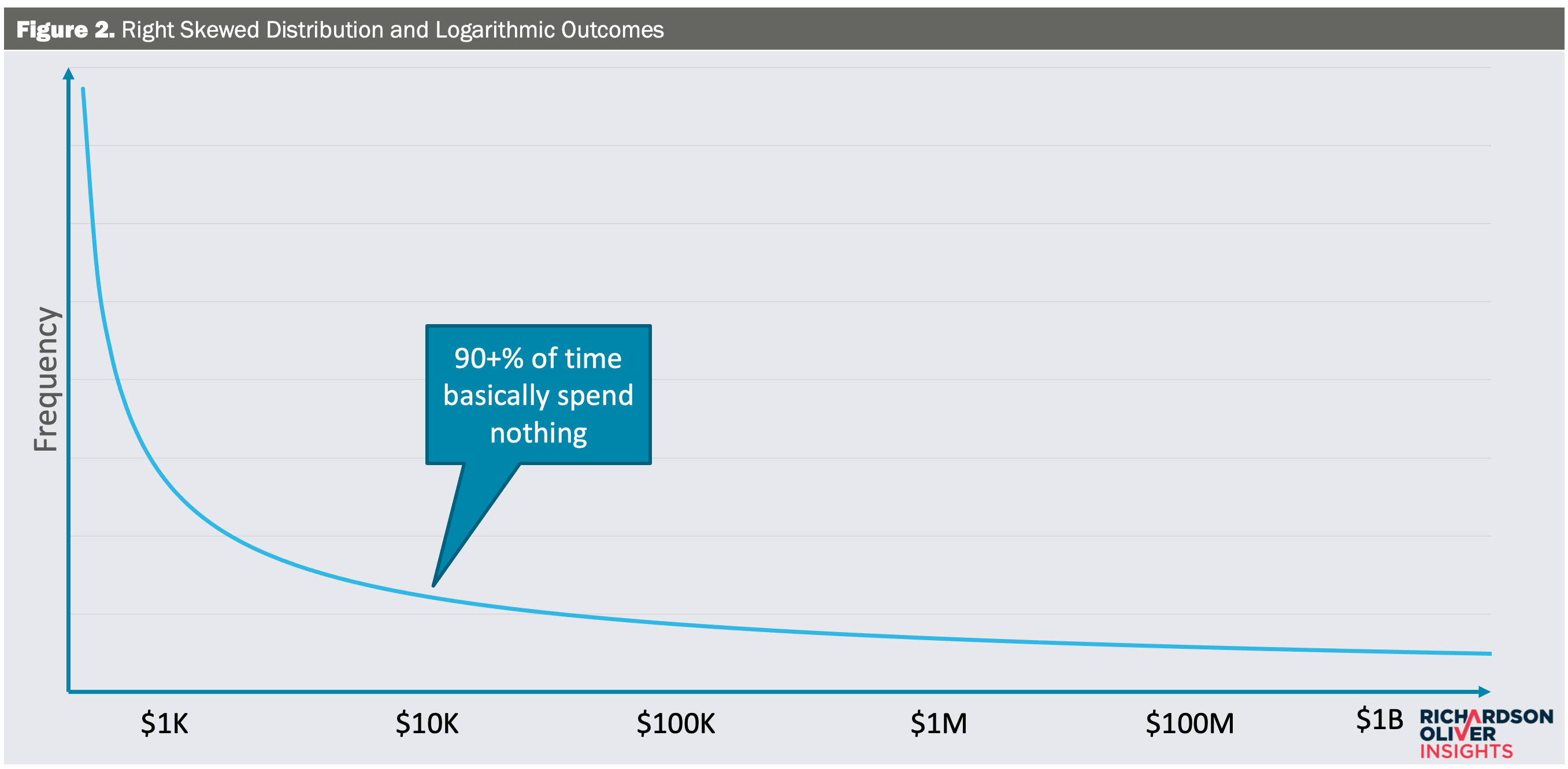

To avoid this problem, the model blends the median for publicly awarded damages with the experience of the IP team, e.g. internal and external litigators. This can be combined with litigation cost estimates (e.g. AIPLA annual Report of the Economic Survey, your negotiated rates with your IP litigation firm, etc.) to create a blended model of costs plus settlement expenses and their likelihoods. For companies that have experienced a large number of lawsuits, they may have sufficient internal data to build this without any external inputs. The model can then blend multiple stages as shown in Figure 3. This shows an expected cost for an operating company suit would be just over $15 million. A similar table with appropriate costs can be completed for non-practicing entities (NPEs) and comes up with numbers closer to $2 million.

One more modeling factor is needed to avoid a different problem: instead of underestimating every suit, this model now suggests every patent that could land with an operating company could cost our company $15 million+ (and $2 million if it goes to an NPE). One more modeling factor is needed, linking these numbers to the probability of the lawsuit occurring, e.g. what is the probability that the patent is bought by someone and asserted against you. Again, the company’s own track record plus public data about the patent market can inform this analysis. Adjusted down for these events, the numbers might come to something more like $0.5 million for NPE risk removal and $3 million for operating companies. (Aside: These are sample numbers only and are not suitable for every company.)

Interpreting the Results

We now have a way to quickly model the value of a patent purchase focused on one context: avoided litigation risks. There are obvious challenges to the model, and two very different patents can produce very similar results, e.g. $0.5M of NPE risk for both. But that level of inaccuracy is acceptable at this stage. The goal was to funnel the discussion more productively.

Returning back to your boss’ question about the worth and impact of the four-patent family purchase being contemplated, the deal is proposed to close at $2 million, but what is the worth of buying these patents to the company? Here, the specific belief we share with our boss is that if we do not purchase these patents, we expect a specific operating company we have challenges with will purchase the patent. Further, two of the four families are the focus of the deal and, internally, there is agreement these are at the “middle of the road” on the company specific adjustments, so the model predicts approximately $6 million in worth from removed operating company risk. Now we can answer our boss’ original question: the worth is $6 million in avoided costs, we plan to pay $2 million, and the impact is $4 million.

But more importantly, we can have a higher quality discussion about the various assumptions that were made. Further, as we bring multiple purchases to our boss and use the same model, the decision process will be more consistent.

Simple tweaks to the model can take into account the time-value of money and the company specific hurdle. For example, if the numbers were closer, e.g. only $2.1 million of worth so the impact is $0.1 million, should your boss approve the deal? Often times, companies have internal hurdle rates that proposed engineering projects need to reach. If the project does not produce at least an 1XX% return it does not get approved. A similar approach could be applied here. In keeping with the KISS principles, this model can be extended to additional contexts like improvements in cross-licensing spend and avoided design around costs.

Simple Models, Big Improvement

Across these two articles we have provided a framework for making simple (KISS principle) models that provide a mechanism for quickly obtaining market price and worth (or value) of patents. Adopting these tools internally can provide a big improvement to the quality of decision making around patent acquisitions, or spin outs. These models will typically be followed up by more detailed market pricing or valuation approaches if the deals proceed. Those approaches can be significantly more complicated and thus provide a more nuanced and accurate estimation.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:50390993

Copyright:IzelPhotography

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Pro Say

September 30, 2020 03:12 pmI’m sure I speak for many in expressing thanks for a great job guys.

ChrisW

September 30, 2020 11:10 amThis is sooo important of a topic, its right where the rubber hits the road – at the commercial level. What one wants, when management asks their value question, is to have the entire scenario wrapped up as a no-brainer decision, either to acquire or walk. I’d wager one might be able to make the vast majority of these to be no-brainers, but that pesky 20 or so % of the remainder, can be murky.