“Artists, lawyers and investors must act earlier and smarter if they want to rely on trademark protection to establish control.”

One of street artist Banksy’s most iconic images—a mural sprayed on a Jerusalem building of a protester preparing to hurl flowers—failed to win trademark approval from the European Union in September because the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) doubted the sincerity of his attempt to merchandise the image.

One of street artist Banksy’s most iconic images—a mural sprayed on a Jerusalem building of a protester preparing to hurl flowers—failed to win trademark approval from the European Union in September because the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) doubted the sincerity of his attempt to merchandise the image.

Banksy had hoped that the trademark would prevent unauthorized use of the image by a greeting card company, Yorkshire-based Full Colour Black. Famously private, the artist elected the unorthodox strategy of seeking trademark protection. The EUIPO said the artist’s company, Pest Control, had filed the mark in order to avoid using copyright laws, which would have required him to reveal his true identity—something he has managed to keep hidden for more than 15 years. (There are many theories about Banksy, including the possibility that he is a “we,” not a single individual but a team of street artists or artisans assisting him.) A copyright also would have limited the term of coverage.

Sprayed on a Wall

“Flower Thrower” was first sprayed on a wall in Jerusalem in 2005, and Banksy’s company applied for the trademark in 2014. Since it was created, it has been viewed on the internet, in print and live by tens of millions of people.

Banksy – Love Is In The Air, Flower Thrower, 2005, Ash Salon Street, Bethlehem, West Bank, photo: CC BY 2.0 by jensimon7, used under the Creative Commons copyright, https://publicdelivery.org/banksy-flower-thrower/

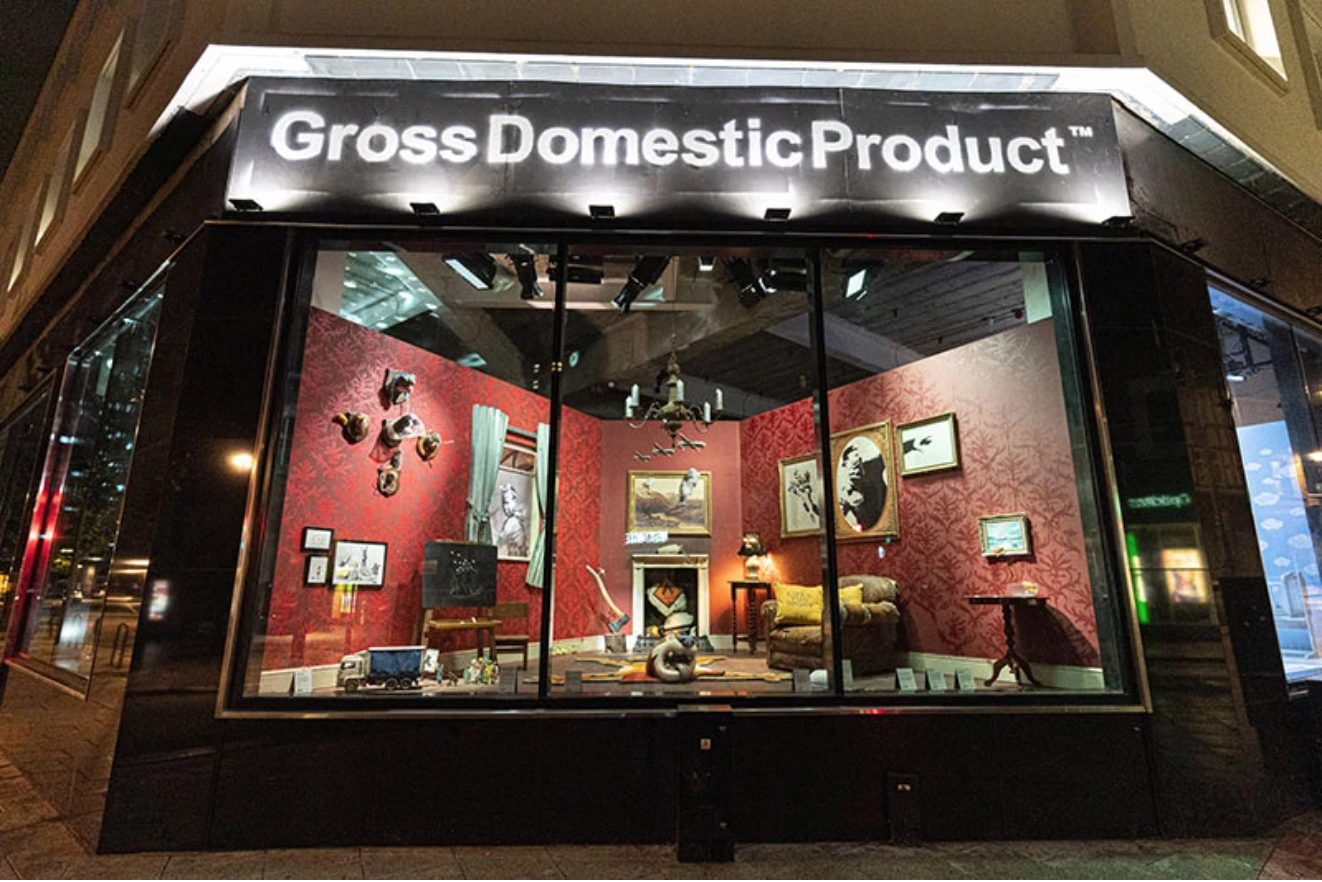

The EUIPO said the artist hadn’t sold merchandise or other items using the image until Full Colour Black challenged the trademark in 2019. The law says the mark must be used within the first five years and enforced, if necessary. Only when he thought he must did Banksy set up an online store, Gross Domestic Product, and a pop-up in Croydon, South London. He said that he had been “making stuff for the sole purpose of fulfilling trademark categories under EU law.”

Social Critic

The shop, which looks more like an art installation than a store, attracted huge crowds but closed after two weekends in October 2019. The EUIPO said it was “clear that Banksy did not have any intention of using the trademark when he filed it, “and that in 2019 the goods he sold “were created and being sold solely” as an attempt not to lose the trademark.

Source: twistedsifter.com

Banksy, as much a social critic and satirist as an artist, said in his 2005 book, Wall and Piece, that “copyright is for losers.” (See IP CloseUp for more background.) His failed attempt to protect “Flower Thrower” from unauthorized use may have made him a trademark loser, but only in a manner of speaking. Banksy is keenly aware that the value of notoriety. He wins even when he loses if the controversy is sufficiently intriguing. His riffing on the art and IP worlds is serious but cannot be taken too seriously. (Banksy apparently is attempting to mark Gross Domestic Product but neglected to do so for its tagline,

Arts lawyer Mark Stephens, who has advised him, said at the time: “Banksy is in a difficult position because he doesn’t produce his own range of shoddy merchandise and the law is quite clear – if the trademark holder is not using the mark then it can be transferred to someone who will.” (I do not believe the law requires the merchandise to be shoddy for legal purposes, but I could be wrong.)

Drawing the Line: Trademark vs. Copyright

The case raises important issues: Copyright and trademark are fundamentally different and are not interchangeable. Artworks cannot be monopolized by simply marking them. While copyright intends to protect content such as paintings and images for a period of time, trademarks typically cover logos and signs that help consumers to make informed choices when it comes to buying products. They are not granted for artists to control how their works are used or viewed – but could they be? It may be a matter of establishing just what is meant by “merchandise,” and how early its relationship to a particular image needs to be established.

Source: twistedsifter.com

Copyright is granted for limited time (until 70 years after death of the author in the EU; a similar term in the US; works for hire in the United States are up to 120 years), while trademarks can be continuously renewed; trademarking an artwork provides an artist a perpetual “monopoly.” This violates an IP principle that after a specific period of time everyone should be able to access, use, and build upon works that have become part of the public domain.

Was Banksy’s intention to prevent all sharing in order to profit better and longer from his work, or was he simply interested in retaining the option to choose how the works are used, with the intention of maintaining their integrity?

The Commission is saying that if you use trademark for protection you need to commercialize the underlying image or symbol, and not gratuitously. Works that are registered and enforced as trademarks, such as Disney’s characters, must do so in “a genuine way, with merchandise regularly produced and sold by the rights holder.” Banksy’s trademark squabble could encourage artists to merchandize their work earlier – and more specifically, before others do – in order to maintain control. Defining merchandizing is another matter.

“You can still be anti-establishment and take legal action to protect your intellectual property,” says Enrico Bonadio, a reader in intellectual property law at City University, London. “But what you can’t do is behave as Banksy did in creating his shop to simply get around the law and keep perpetual monopolies over his art.”

For its part, Full Colour Black, is a perplexing enterprise. Its main product line appears to be about a dozen greeting cards taken from Banksy images. It also sells a line of humorous and photographic cards which may or may not be licensed. The site, which has UK and U.S. versions, is difficult to navigate, at times defaulting to a website design firm, Tilda Publishing (tilda.cc). “.cc” is the Internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Cocos (Keeling) Islands, an Australian territory of 5.4 square miles and about 600 inhabitants.

According to the FCB website, “We are a contemporary Art Licensing company specialising in the commercialisation of world famous street art.”

The EUIPO noted that illegal graffiti cannot be protected by copyright because it is produced through the commission of a criminal act. It added that as graffiti is normally placed in public places for all to view and photograph, no copyright can be claimed. Bonadio argues that “these statements are not accurate. The process of creating an artwork, whether legal or illegal, is not conclusive when it comes to determining whether copyright comes into existence.”

“If I steal a pencil and create a wonderful drawing,” he says, “why should I be denied copyright and be forced to tolerate someone else cashing in on my work? It would be unfair. The same could be said of illegal street art. Also, the fact that graffiti is placed in public locations does not assume that artists waive or are deprived of the rights copyright law offers them. That is simply mistaken.”

Pest Control

Banksy’s failed attempt to use EU trademark law to protect his work did not prevent the experience from resulting in another Banksy event, similar to the destruction of “Balloon Girl” after purchase at a London auction in 2019. (The partial shredding, in fact, increased the work’s value.) Deconstructing the ideas of originality, ownership and control – concepts he appears to reject – has long been a part of Banksy’s droll iconography. “It’s all very meta isn’t it?” said an observer referring to the self-referential nature of the experience. Banksy responding to responses to his work makes it impossible to exclude them from his art.

“There are these very serious market messages and this trademark legal dispute – all very boring, turgid things if you look at them in isolation,”Art Newspaper correspondent Anny Shaw told the BBC . “But he’s managed to flip it into something rather brilliant.”

If Banksy is intent about controlling his works through trademark, he will have to establish that he is actively using them on merchandise or other products for sale—distasteful to the artist on one level, but an opportunity to engage in pest control on another.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

8 comments so far.

Anon

October 25, 2020 09:22 amThank you Bruce – some fun reading for me today.

Bruce Berman

October 23, 2020 03:05 pmThe U.S. covered artists moral rights in the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990.

Anon

October 23, 2020 11:50 amBruce,

Interesting points. Is the US one of those 60 nations?

Bruce Berman

October 23, 2020 10:06 amMore than 60 nations protected artists’ moral rights. My understanding that artists still have rights to the copyrighted work that they create even if ownership is transferred.

This could be complicated for street artists the placement of whose work may be “illegal” to begin with but may still be copyrightable. Does removal of alteration of their work then constitute defacement?

“The concept of moral rights protects the rights of a creator of a work of visual art to claim or disclaim authorship of his or her work (the right of paternity or droit la paternite, and the right of disavowal); to decide when to publish or reveal the work to the public (the right of disclosure or droit de divulgation); to withdraw the work from publication or make modifications to the work (the right of withdrawal or modification or droit de retrait or de repentir); and to prevent the defacement or alteration of the work (the right of integrity or droit au respect de l’oeuvre).”

https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/do-artists-have-moral-rights

Anon

October 22, 2020 07:27 amI think that the more interesting aspect of this article is the attempt to illuminate the plain fact that different forms of IP are meant to protect different things.

Trademark (in the US) even stems from a different section of our Constitution.

Legal counsel should have been obtained by Banksy here and that counsel should have informed Banksy of the pitfalls of his attempt.

Mitch G.

October 21, 2020 01:01 pmhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Works_by_Banksy_that_have_been_damaged_or_destroyed

Hmm, seems Banksy is aware of and accepting of the fact his works get painted over or defaced by other artists, so now I’m really curious how he views potential IP rights assertion.

He admits “overwriting and defacement was an inevitable reality of street art.”

Richard Baker

October 21, 2020 11:42 amCould Pest Control have filed a Community Design for an artistic medium with the flower thrower design on it to protect the design?

Mitch G.

October 21, 2020 11:25 amIf there is copyright in graffiti, what happens if the property owner decides to remove the artwork. It is their wall, and the art was created on their property without permission.

Guess we need a person who doesn’t care about Banksy or is just sick of the added foot traffic due to Banksy fans to powerwash or paint-over one of the works.

It would be interesting to see the Banksy response at least.