“I suspect that the law does allow Director Iancu to create rules interpreting Section 101, at least within the limited context of the America Invents Act’s post-grant review trials.”

Since U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Director Andrei Iancu took office, I have observed, with admiration, how he has taken bold action to improve perceived problems in the patent system. For example, in my public comments on the 2019 USPTO guidance on patentable subject matter law under 35 U.S.C. § 101, I observed that: “the Revised Guidance appears to constitute the most aggressive attempt yet by the Office to influence the law of patentable subject matter through policymaking guidance.” Similarly, the bold actions taken by the Director to improve post issuance proceedings at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) recently motivated 324 American innovators and patent owners to write publicly to Congress supporting the Director’s accomplishments. In addition to the 2019 USPTO guidance and the various improvements to PTAB procedures, Director Iancu has also spoken widely in public to advocate for further improvement, and the USPTO under his direction has filed helpful amicus briefs in infringement litigation suits on issues related to the courts’ treatment of Section 101.

Since U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Director Andrei Iancu took office, I have observed, with admiration, how he has taken bold action to improve perceived problems in the patent system. For example, in my public comments on the 2019 USPTO guidance on patentable subject matter law under 35 U.S.C. § 101, I observed that: “the Revised Guidance appears to constitute the most aggressive attempt yet by the Office to influence the law of patentable subject matter through policymaking guidance.” Similarly, the bold actions taken by the Director to improve post issuance proceedings at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) recently motivated 324 American innovators and patent owners to write publicly to Congress supporting the Director’s accomplishments. In addition to the 2019 USPTO guidance and the various improvements to PTAB procedures, Director Iancu has also spoken widely in public to advocate for further improvement, and the USPTO under his direction has filed helpful amicus briefs in infringement litigation suits on issues related to the courts’ treatment of Section 101.

The Director’s bold action has also caught the attention of members of the Supreme Court. Justice Gorsuch, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, observed, “[n]or has the Director proven bashful about asserting these statutory powers to secure the [policy judgments] he seeks.”

Oil States Energy v. Greene’s Energy Group, 138 S.Ct. 1365, 1381 (2018) (Gorsuch, J., dissenting).

I wonder, however, whether the law now permits Director Iancu to do something even bolder: create rules interpreting Section 101, at least within the limited context of the America Invents Act’s (AIA’s) post-grant review trials, such that courts may defer to the Director’s interpretation under Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984).

Cuozzo’s Implications for Substantive Rulemaking on 101

I suspect that the law does allow Director Iancu to create such rules. My suspicion here derives primarily from what Justice Breyer wrote for a unanimous Court in Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee, 136 S.Ct. 2131 (2016). In Cuozzo, Justice Breyer encountered the argument, which is popular with certain circles of the patent bar, that the Director is forbidden, by statute, from creating rules on substantive patent law, including questions regarding 35 U.S.C. §§ 101, 102, 103, and 112. See generally id. at 2143. Instead, the argument goes, the Director is limited to purely procedural rulemaking powers. Id. This argument derives from the pre-AIA grant of statutory authority to the Director at 35 U.S.C. § 2, which uses the keyword “proceedings,” thus implying that the Director is limited to purely procedural rulemaking powers.

Interestingly, both the original Federal Circuit panel majority in Cuozzo, as well as the Federal Circuit judges who dissented from the denial of en banc review, concluded, or at least suggested, that the Director is limited to procedural rulemaking. Judge Dyk, writing for the original panel majority over a dissent by Judge Newman, wrote:

We do not draw that conclusion from any finding that Congress has newly granted the PTO power to interpret substantive statutory “patentability” standards. Such a power would represent a radical change in the authority historically conferred on the PTO by Congress, and we could not find such a transformation effected by the regulation-authorizing language of § 316 any more than we could infer a dramatic change in PTO claim interpretation standards through the general language of the IPR provisions.

In re Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC, 793 F.3d 1268, 1279 (2015). Similarly, in the dissent from denial of en banc review, Chief Judge Prost wrote the following, joined by Judges Newman, Moore, O’Malley, and Reyna:

It is far from clear to us that this is a case in which we must defer to the PTO’s action. The panel majority bases its conclusion on subsections (2) and (4) of § 316. In our view, these subsections are consistent with Congress’s previous grants of authority to prescribe procedural regulations. Cooper Techs. Co. v. Dudas, 536 F.3d 1330, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (interpreting 35 U.S.C. § 2). (emphasis in original)

In re Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC, 793 F.3d 1297, 1302 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (Prost, J., dissenting from denial of en banc review).

In a move that seems to have escaped the attention of some patent lawyers, Justice Breyer flatly rebuked this argument that the Director is limited to procedural rulemaking powers due to the keyword “proceedings” in 35 U.S.C. § 2. Justice Breyer wrote:

The dissenters, for example, point to cases in which the Circuit interpreted a grant of rulemaking authority in a different statute, § 2(b)(2)(A), as limited to procedural rules. See, e.g., Cooper Technologies Co. v. Dudas, 536 F.3d 1330, 1335 (C.A. Fed. 2008). These cases, however, as we just said, interpret a different statute. That statute does not clearly contain the Circuit’s claimed limitation, nor is its language the same as that of § 316(a)(4). Section 2(b)(2)(A) grants the Patent Office authority to issue “regulations” “which … shall govern … proceedings in the Office” (emphasis added), but the statute before us, § 316(a)(4), does not refer to “proceedings” — it refers more broadly to regulations “establishing and governing inter partes review.” The Circuit’s prior interpretation of § 2(b)(2)(A) cannot magically render unambiguous the different language in the different statute before us.

Cuozzo, 136 S.Ct. at 2143. This key passage is found in Section III of Justice Breyer’s opinion, which was joined by a unanimous Court.

In my view, the Supreme Court could hardly have been clearer. The Director’s rulemaking powers under the AIA are “more broad[]” than the general, “procedural” powers granted in 35 U.S.C. § 2. See id. The Director’s powers under the AIA are not limited to purely procedural rules. Even if the Director was previously limited to procedural rulemaking in an earlier era, the AIA has changed that. The fact that the Director is not limited to procedural rules implies naturally that the Director has some substantive rulemaking power. The Director can now advocate for substantive rulemaking authority that the Federal Circuit denied to his predecessors in the pre-AIA era. For example, the power at issue in Cuozzo was the power to decide the standard for claim construction, which is arguably not purely procedural.

Indeed, Cuozzo not only strongly suggests that the Director has some substantive rulemaking power in the context of AIA trials, it also suggests that the Federal Circuit’s prior limitation to “procedural” rulemaking has always been questionable. Specifically, Justice Breyer wrote that: “§ 2(b)(2)(A) […] does not clearly contain the [Federal] Circuit’s claimed limitation [to procedural rulemaking], nor is its language the same as that of § 316(a)(4).” 136 S.Ct. at 2143. The implications of this statement are remarkable—the unanimous Supreme Court is casting doubt on a sharp limitation on the Director’s powers that has been respected by the Federal Circuit and USPTO for decades.

The View from Academia

The conclusion reached by the unanimous Court in Cuozzo—that the Director is not limited to procedural rulemaking in the AIA context—was arguably anticipated by several law professors during the development and promulgation of the AIA. See, e.g., Karen A. Lorang,

The Unintended Consequences of Post-Grant Review of Patents, 17 UCLA J.L. & TECH. 1, 31 (2013); Arti K. Rai, Improving (Software) Patent Quality Through the Administrative Process, 51 HOUS. L. REV. 503, 540 (2013); Arti K. Rai, Patent Validity Across the Executive Branch: Ex Ante Foundations for Policy Development, 61 DUKE L.J. 1237, 1239 (2012); Melissa F. Wasserman, The Changing Guard of Patent Law: Chevron Deference for the PTO, 54 WM. & MARY L. REV. 1959, 1965 (2013); and Stuart Minor Benjamin & Arti K. Rai, Who’s Afraid of the APA? What the Patent System Can Learn from Administrative Law, 95 GEO. L.J. 269, 327–28 (2007).

In contrast, at least one noted law professor, John M. Golden, reached the opposite conclusion. John M. Golden, Working Without Chevron: The PTO as Prime Mover, 65 DUKE L.J. 1657, 1674 (2016). In particular, Professor Golden relies on the principle of statutory construction whereby Congress “does not, one might say, hide elephants in mouseholes.” Id. at 1675 (quoting Whitman v. American Trucking Assns., Inc., 531 U.S. 457, 468 (2001)). Indeed, Professor Golden cites the Federal Circuit’s Cuozzo opinion from the original panel to support the limitation on the Director’s rulemaking powers.

In my view, although it pains me to disagree with Professor Golden, his argument that the Director’s powers remain purely procedural, because Congress does not “hide elephants in mouseholes,” consistent with the original Federal Circuit panel majority in Cuozzo, does not fit with what Justice Breyer later wrote in Cuozzo.

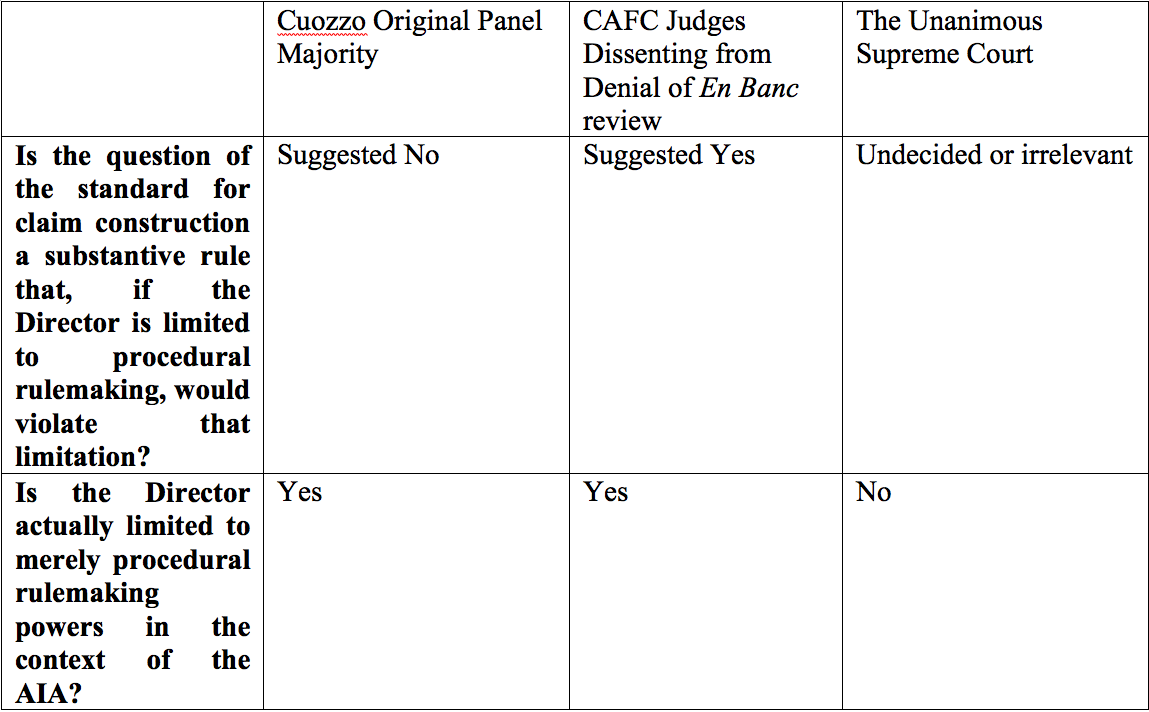

We can chart the holdings (both explicit and suggested) as follows:

As we can see, both the original panel majority and the dissenting judges answered “yes” to the question of whether the Director is limited to procedural rulemaking. They reached different decisions, not because they disagreed about whether the Director is limited to procedural rulemaking, but instead because they disagreed about whether this limitation was violated, as shown in the chart above. In contrast, the Supreme Court sharply contradicted the dissenting judges regarding the Director’s limited rulemaking powers, and thereby implicitly contradicted the panel majority on this point (i.e., rendering that portion of the original panel majority opinion dicta): the Director is not limited to procedural rules in the context of the AIA, and this implies that the Director has some substantive rulemaking power. 136 S.Ct. at 2143. One cannot fault Professor Golden on this point because his article was originally published in 2015, prior to the Court’s opinion in Cuozzo and, therefore, Professor Golden did not have the benefit of seeing how the Court would rule.

The Director Arguably Has Broad Authority

The fact that the Supreme Court left the door open for the Director to have some substantive rulemaking power does not answer the question of which specific substantive rulemaking powers the Director has or what are the precise boundaries of his authority. Nevertheless, a careful reader can infer that, in Justice Breyer’s view, the Director’s powers are quite broad. Indeed, Justice Breyer in Cuozzo does not clearly classify the claim construction question as “substantive” or “procedural.” Instead, Justice Breyer’s opinion suggests that, rather than focusing on the substantive/procedural distinction, the relevant analysis is quite literal: “the statute allows the Patent Office to issue rules ‘governing inter partes review,’ § 316(a)(4), and the broadest reasonable construction regulation is a rule that governs inter partes review.”

136 S.Ct. at 2142. Similarly, I would suggest, and Director Iancu may argue, that a rule regarding how administrative patent judges shall interpret § 101 is a “rule that governs” post-grant review trials (i.e., because the relevant post-grant review statute, 35 U.S.C. § 326, echoes the language of § 316(a)(4) discussed in Cuozzo: “The Director shall prescribe regulations […] governing a post-grant review”) (emphasis added).

Admittedly, the strategy that I outline here creates the potential for a bifurcated body of Section 101 interpretations between the USPTO and the courts, yet this bifurcation flows naturally from differences in respective statutory grants of power. It is not clear to me that, to the extent an inconsistency exists, this inconsistency is intolerable. The Supreme Court in Cuozzo itself already blessed the bifurcation of claim construction standards between post-issuance proceedings and patent litigation, for example. Specifically, the Supreme Court held in Cuozzo that the Director may decide the standard for claim construction in inter partes review, and may select the “broadest reasonable interpretation” standard (as in during examination), rather than the standard applied in traditional litigation. The Supreme Court held that the Director may create an inconsistency in claim construction between the USPTO and the courts because “the possibility of inconsistent results is inherent to Congress’ regulatory design.” 136 S.Ct. at 2146. Director Iancu can make a parallel argument, in the context of interpreting Section 101, that “the possibility of inconsistent results is inherent to Congress’ regulatory design” embodied in the post-grant review statutes. Even if a bifurcation of Section 101 law is intolerable, it is not clear to me that the inconsistency should be resolved against the Director. The courts arguably created problems that are widely acknowledged regarding Section 101 law, and perhaps the Director can do better. Even in a scenario where bifurcated Section 101 law becomes a practical reality, Congress may act readily to resolve that outcome. In any event, as the Court held in Cuozzo, “the statute before us, § 316(a)(4)” is “more broad[]” than 35 U.S.C. § 2. 136 S.Ct. at 2143. The patent system must manage the practical consequences created by this difference in rulemaking powers without pretending that there are no such consequences.

Toward Amendment

In view of the above, I sent a letter to the Director (USPTO), the Commissioner for Patents, and the Office of the Solicitor (USPTO). The letter provided more detail regarding the statutory and jurisprudential background for this strategy to improve the law of patentable subject matter, the strength of that strategy (while acknowledging potential weaknesses of the strategy), and examples of model regulations that the Director may promulgate. The issues here are quite complex and nuanced, and the letter provides a more comprehensive defense of my argument than a blog post can.

Included in the letter linked above is my preferred amendment to 37 C.F.R. § 42.200 that the Director may promulgate to try to improve the law of Section 101. This model regulation is based on my earlier IPWatchdog article, “Alice’s Tourniquet: A Solution to the Crisis in Patentable Subject Matter Law.” The model regulation attempts to achieve some success, where the Federal Circuit has struggled, in interpreting certain more challenging parts of Supreme Court jurisprudence on patentable subject matter. Of course, my preferred amendment here is just one attempt to demonstrate the general strategy, and to begin a dialogue on this topic. The USPTO and the patent bar can likely devise an even better amendment to § 42.200.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:27251091

Copyright:filmfoto

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

35 comments so far.

Anon

November 23, 2020 09:51 amLikewise – (look at your hands, ‘Mr. I’m So Mature’).

You lobbed insults before – with your only “justification” being that you felt insulted in the manner that I showed that you were wrong; and you do so again here, even as you admit that I was right, with your odd ego-preserving recollection AND still sliding into the odd “it must be criminal law” level treatment.

As before, the only one amiss here is you. You can indulge in your ego all that you want, and when you decide to put on your big-boy pants and actually discuss the legal matter, I will still be here.

David Boundy

November 23, 2020 08:00 amanon —

It’s no fun writing for people that don’t read carefully or don’t think clearly. So I’ll put you back on my “don’t bother” list. I gave you benefit of doubt that you might have matured with time. My error. Apologies for taking your time to write that rant.

David

Anon

November 22, 2020 10:17 pmNice enough of the editors to clean up the mess you made with, what was it, 8 attempts to make an ‘typo free’ post.

Sadly, this only draws more attention to your not really ‘getting’ the blogging forum here, Davey.

Blog posts (and especially comments therein) NEED NOT be so meticulous as to form, and they are MEANT for a more rapid fire, ready wit, exchange.

Sure, being correct IS important, but even on that note, your ‘meticulousness’ just does not rise high enough in your post.

“ I remember the conversation well enough”

Apparently not so

“ any invasion must be “narrowly tailored” to a valid state interest.”

True enough – but YOU misplay this notion with YOUR assertion that the extra-statutory law WRITING (and explicitly NOT gap-filling interpretation) BY the Supreme Court may be deemed proper, notably in NOT being Void for Vagueness – but we will come back to this in a bit – but keep in mind here that – as you state – THE INVASION – must be narrowly tailored (that is, the law doing the invading, and NOT the right itself per se), as I will want you to contrast this with the presence of the right itself, which need not be an item so ‘narrowly tailored, as you seem to want to switch these things.

“ambiguity leads to a “chilling” effect on Constitutionally-protected activity”.

This is exactly what happens with the Supreme Court’s re-writing on patent eligibility.

There is a most definite ‘chill’ on innovation (as has been noted across the blogosphere AND the halls of Congress. Maybe you were taking a nap during those discussions.

“ Criminal law is similar”

And there you go again…

Not sure exactly WHY you want to fall back to something that I have corrected you on.

Well, I DO have a feeling why. You really did not like the fact that this ‘upstart’ anonymous web guy showed you up on a legal point and corrected you. You have ALWAYS held a grudge on that point, as you were so DAMM sure that you were correct.

“Property” isn’t one of the interests that gets “narrowly tailored” scrutiny”.

That’s a flat-out bold assertion that simply needs more. It’s also an assertion that ‘flips’ the focus. It is NOT whether or not AN ITEM ‘gets’ narrowly tailored scrutiny, it is whether the particular item HAS LAWS that do NOT get narrowly tailored scrutiny.

And ‘property’ IS one of the Big Three – AND that was the point that I rubbed your nose in it long ago, proving your wrong BECAUSE you wanted only Criminal Law.

“ Take a look at the Sherman Antitrust Act [_]…to assure yourself… doesn’t apply to commercial/economic statutes!”

Non sequitur, and logical error on your part. Just because ONE particular commercial economic statute may not invoke a Void for Vagueness application, such has ZERO tie to the Constitutional Power provision of the Patents Clause.

You simple seek too much and err in your OVER-ASSumptions.

“You corrected my over-simplified post several years ago”

…and again here, as you – yet again – over-simplify and over-ASSume.

“I wrote back to agree… I observed that…”

LOL – is that how you are choosing to remember it?

You wrote back in a sullen fit of rage ONLY after I provided writings by known (named) authors that VALIDATED my position. You made NO SUCH ‘observations,’ and you VERY QUICKLY exited the conversation without actually addressing the points that I had put to you. As I recall, that earned you MY ‘syllogism’ of comparing you to the likes of Malcolm Mooney, who also only too often played that game of not engaging on points that one does not like.

“There’s still no “narrowly tailored” Constitutional interest at stake.”

Again – this is merely YOUR overly broad assertion. Quite clearly, the Patent Clause is a Constitutional interest, as well as is the Separation of Powers doctrine that is ALSO at stake with the Supreme Court’s legislating from the bench (and in other conversations, notably to Night Writer, I have ALSO put forth other Constitutional issues, such as the presumptive and projective “such MAY [in the future] harm innovation” that the Supreme Court relies on for their ‘authority.’

As I also recall, I took you to task for the LACK of holding the Supreme Court to task on ethical grounds. On that point, I will cut you some slack, as you have been the only one to have responded on point with a sharing of which State’s oath you had in mind, and there is a slender reed resting in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ rather unusual direction as to the where the Court or the Constitution has supremacy.

“From that point you went off on some non sequitur that was so absurd that I don’t recall it now.”

…and there you go again.

(Reagan ‘syllogism: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qN7gDRjTNf4 )

YOUR assertion of ‘so absurd’ was me merely your nose in the ego-driven problem of YOU being wrong and unwilling to admit that someone – with a point opposing yours – was absolutely correct.

“That was several years ago; let’s see if your cerebral cortex has matured a bit.”

Let’s see of yours has (or maybe just your ego has been suitably put in check), as the past error was yours, and you seem intent on NOT remembering that situation correctly.

“’Void for vagueness’ is not a free-standing principle… extends only where an interest is subject to a “narrowly tailored” or criminal law requirement.”

WRONG – here, you AGAIN attempt to slip back into the ‘criminal law’ view, EVEN as you (it must be so humbling), half heartedly ADMIT THAT I WAS CORRECT, that criminal law is simply NOT the requirement that you attempt to make it (by ‘syllogism’ or otherwise).

Your own listed first principles (but my emphasis):

“* the invaded interest has to be “life, liberty, or property””

(My correction of you)

“* and there has to be a state actor (i.e., a private sector party can’t violate due process)”

Nice strawman there – as I never implicated a private sector party violating due proves, PLUS, Supreme Court WRITING patent law certainly qualifies as a State Actor.

“* for a due process “void for vagueness” issue[with the law], the interest has to be one of the “narrowly tailored” Constitutional interests.”

Read again your first point in this stanza – and don’t choke on your past retreat to recognize property as a critical interest (and please, no strawman of commerce instead of property).

“fails to address two of the three reasons”

Balderdash

* “Property” isn’t relevant to the state actor prerequisite for due process, at least not in post-issue contexts”

There you go again – a bald assertion without substantiation on your part, that is directly contradicted by your admission that I was correct, as you hurry back to some ‘criminal law’ basis, that just is NOT as you assert it to be.

If YOU want to establish this, I would be interested, but please, I need more than “because Davey said so in a huff.”

“’Property’ isn’t a magic word that has the slightest relevance to applicability of ‘void for vagueness.’”

Not the slightest? That’s easily a wrong statement – by your own very ‘meticulous; words of THIS post.

David Boundy

November 21, 2020 01:09 pmGreg @19 and anon @ 26 –

I remember the conversation well enough. I observed that “void for vagueness” applies only where a constitutionally-protected interest (typically criminal law, Fifth/Fourteenth Amendment “life, liberty, or property,” or First Amendment) is involved. For some (but not all) Constitutionally-protected interests, any invasion must be “narrowly tailored” to a valid state interest. The rationale of “void for vagueness” is that a vague statute isn’t “narrowly tailored,” and therefore the ambiguity leads to a “chilling” effect on Constitutionally-protected activity. It’s unacceptable for a statute to chill Constitutionally-protected activity beyond a narrowly-tailored scope. Criminal law is similar: because it’s the power of the state seeking to impose criminal (or quasi criminal “civil penalties”) penalties, the line between prohibited and not-prohibited conduct must be clear.

“Property” isn’t one of the interests that gets “narrowly tailored” scrutiny.

So, by a syllogism, “void for vagueness” only applies where there’s a Constitutionally-protected interest that requires “narrow tailoring:” life, or First Amendment, or criminal penalties, but not “property.” (I don’t remember whether “liberty” interests have a “narrowly tailored” requirement—doesn’t matter for this discussion.) Take a look at the Sherman Antitrust Act https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/15/1 to assure yourself that “void for vagueness” doesn’t apply to commercial/economic statutes!

You corrected my over-simplified post several years ago to observe that “void for vagueness” isn’t limited to only criminal, because it also applies to “civil penalty” cases.

I wrote back to agree that “civil penalties” can be within due process (I observed that several other Constitutional criminal protections have been extended to apply to civil penalty cases), but I observed that your observation does nothing whatsoever to bring patent law within due process. There’s still no “narrowly tailored” Constitutional interest at stake.

From that point you went off on some non sequitur that was so absurd that I don’t recall it now. I do recall that I concluded that you were too reading-impaired to be worth further discourse.

That was several years ago; let’s see if your cerebral cortex has matured a bit.

Let’s go back to first principles. Read the first three paragraphs of this post again. Read them one more time, carefully. Now do you get it? “Void for vagueness” is not a free-standing principle that applies across all law. It extends only where an interest is subject to a “narrowly tailored” or criminal law requirement. For “void for vagueness” to apply, the specific interest has to be one that gets “narrowly tailored” treatment from the Constitution, or one with criminal (or “civil penalties”) consequences.

Let’s give first principles another look, from another direction. There are several separate conditions for any due process issue:

* the invaded interest has to be “life, liberty, or property”

* and there has to be a state actor (i.e., a private sector party can’t violate due process)

* for a due process “void for vagueness” issue, the interest has to be one of the “narrowly tailored” Constitutional interests.

Your post fails to address two of the three reasons that “void for vagueness” doesn’t apply to patents.

* “Property” is a necessary condition (or rather one of three alternative necessary conditions.). “Property” is not a sufficient condition for applicability of the due process clause.

* “Property” isn’t relevant to the state actor prerequisite for due process, at least not in post-issue contexts (due process could apply while a patent is still in prosecution, but not in a post-issue patentee-v-infringer situation).

* Property interests don’t satisfy the “narrowly tailored” prerequisite for “void for vagueness” to apply.

Therefore, “void for vagueness” doesn’t apply to patent law. “Property” isn’t a magic word that has the slightest relevance to applicability of “void for vagueness.”

David

Pro Say

November 18, 2020 11:12 pmKip — thanks for engaging with the commentators; which is especially valuable given the important, many-faceted aspects and factors present here.

Would be great to see more such engagement from other guest posters.

Kip

November 18, 2020 01:07 pm“Within your proposed reg, the part that catalogs showings that have to be put to paper is a classic “procedural” agency-facing regulation. That part is validly promulgated, within the Director’s authority, and binding against agency staff even in courts.”

I’m not sure that PGR petitioners would agree with you so easily. At least some creative petitioners would argue that my model regulation violates Cooper Techs, Windy City, and related case law.

“the idea of requiring defined showings is a good one”

Thanks, David. That means a lot coming from you .

David Boundy

November 18, 2020 11:04 amKip —

further thoughts.

I don’t agree with the specifics of your list of showings that have to be made, but the concept is on target.

One example — “looping computation.” That has never been relevant to any court as a criterion. So that part of your proposal is off-target (and would be a change to substantive law, and therefore invalid), but the idea of requiring defined showings is a good one.

David

David Boundy

November 18, 2020 10:57 amKip —

Have you ever heard the expression “burying the lede?”

Within your proposed reg, the part that catalogs showings that have to be put to paper is a classic “procedural” agency-facing regulation. That part is validly promulgated, within the Director’s authority, and binding against agency staff even in courts.

Neither the “procedural vs. substantive” line nor Chevron enter into that part of the reg. At least for that part of your proposed reg, those are complete red herrings.

David

Pro Say

November 18, 2020 10:54 am“It is within the powers of the USPTO Director to issue an Administrative Order, under the Administrative Procedures Act, to all USPTO examiners and judges to NOT make use of 101 caselaw in any decision, by declaring that collectively, 101 caselaw violates Due Process Public Notice for being completely vague in being collectively completely contradictory. Kappos did something similar with his “non-transitory” memo in 2010 (sadly, too many patent lawyers and examiners ignored it). Currently, the USPTO violates the APA by allowing examiners to base rejections on the fatal vagueness of 101 caselaw.”

Bingo Greg.

Bingo.

Leave the courts to Congress.

You know; just as our Constitution instructs.

Anon

November 18, 2020 10:44 amMr. Boundy’s views on the limitation of Void for Vagueness remain off.

I do not have a link saved, but last I visited this in detail, I provided not just my views and reasoning, but a learned treatise that clearly evoked that Void for Vagueness applies in the civil matters related to the property that is patents.

Kip

November 18, 2020 10:24 amDavid,

Let me try to reply to all of your many objections.

“Another weak link in the chain. An agency gets Chevron (or Auer) deference for its independent judgment in resolving ambiguity in statute (or regulation). Agencies don’t get deference for their interpretations of judicial precedent. So the Chevron link in your chain fails for another reason.”

My view is that this is a false dichotomy. The fact that an ambiguity is found in case law does not prevent the ambiguity from being in the statute. In 101, the ambiguity is in BOTH, because the statute inherits the case law through application.

Additionally, the Director can argue (per my letter) that “It is true that the term ‘abstract idea’ originates with the Supreme Court, yet both the acquiescence rule and the reenactment rule of statutory construction suggest that Congress incorporated previous Supreme Court case law on the limits of patentable subject matter when it adopted modern § 101 in 1952.”

“The ‘non-transitory’ memo was just an adoption or reminder of existing case law. In contrast, what you (and Kip) are proposing is to displace the law that arises from Congress and the courts. The Director doesn’t have that authority.”

Did you get a chance to actually look at the model regulation at the end of my letter? It’s very similar to the argument in your gaming en banc brief on Due Process and 101 at the PTAB: hewing closely to the language and opinions in Bilski and Alice.

Kip

November 18, 2020 10:17 amAnon November 18, 2020 8:12 am

“Does either ‘establishing’ or ‘governing’ give power to change fundamental aspects of patent law (as would be necessary to actually change the strictures of any of 35 USC 101, 102, 103 or 112)?”

Take a look at the model regulation at the end of my letter (linked at the end of the blog post above). Does it “change fundamental aspects of patent law?” Or just clarify what was previously vague? Chevron gives agency heads power to interpret ambiguous in statutes, not to overrule them (“not contrary to law” is one precondition for Chevron).

Kip

November 18, 2020 10:13 amJ. Doerre:

“I doubt that you are contending that the Director can *expand* the scope of patent eligible subject matter beyond the plain text scope of 35 U.S.C. § 101.”

Nobody applies the plain text, so this point is irrelevant. We’re starting with SCOTUS precedent, which is much narrower than the plain text.

“It also seems odd to suggest that the Director can enact regulations that *contract* the scope of patent eligible subject matter to less than that specified by Congress in the plain scope of 35 U.S.C. § 101.”

A clarifying regulation does not really expand or contract – it clarifies. Chevron requires a gap, as in Cuozzo, which the Director can clarify. Everyone agrees that section 101, as applied in PGR, has many gaps and ambiguities in terms of application.

“I guess you could consider the atextual judicial exception as having been implicitly incorporated by Congress into 35 U.S.C. § 101, at which point you could try to gapfill the ambiguiuty therein”

I actually think this is a strong argument, and it is mentioned in my letter to the Director (“It is true that the term ‘abstract idea’ originates with the Supreme Court, yet both the acquiescence rule and the reenactment rule of statutory construction suggest that Congress incorporated previous Supreme Court case law on the limits of patentable subject matter when it adopted modern § 101 in 1952.”).

“if the Court felt it necessary to graft an atextual, implicit exception onto a congressional statute, why would they not also feel it necessary to graft it onto an administrative regulation?”

The argument would be that, per Chevron and related case law, pre-AIA SCOTUS case law on 101 was done without the benefit of agency expertise, much less deference. This pre-AIA law was therefore wholly created by the Supreme Court. It represents a “reasonable” (according to SCOTUS) interpretation of the statute among other competing interpretations. In the absence of any competing authority, the SCOTUS wins. Per Chevron, however, if the Director can offer a different interpretation, and that interpretation is reasonable, and Congress gave the Director the power to issue that interpretation per 36 USC 326(a)(4) (“The Director shall prescribe regulations … establishing and governing a post-grant review), then the SCOTUS under Chevron should defer to the Director – EVEN IF the SCOTUS would prefer its previous, different interpretation.

“Moreover, the Director has already published guidance that is more generous than the approach taken in most courts and which purports to bind the Board.”

The guidance is problematic for many reasons. The CAFC has already said it is not binding and not given deference. It states that applicants have no right to appeal or petition violations of the guidance. And it applies to a forum/context (examination), where the Director is still limited in terms of rulemaking powers. It would be preferable for the Director to interpret 101 in the PGR context (where he arguably has that statutory power), rather than the vice versa situation today. (On this last point, David Boundy thinks the USPTO has the power to make asymmetrical pro-patent rules that bind the USPTO but not the public – I think that’s a hard sell).

“I guess I am not clear on what you evision: would you have him issue a regulation that is plainly contrary to Supreme Court precedent?”

Take a look at the model regulation at the end of my letter (linked at the end of my blog post above). Ask yourself if that is plainly contrary to SCOTUS precedent. The majority of it is actually written in explicit terms that are very faithful to Benson, Flook, Diehr, Bilski, and Alice. Keep in mind also that the SCOTUS is looking for a way out – the Justices recognize that 101 is a mess and they likely want to save face. Deferring to the Director based on additional expertise and experience at the USPTO a decade after Bilski is one way to save face.

“To what end? Challengers get to choose their venue. PGRs are not that common to begin with. The result would just be that no one files a PGR with a 101 challenge. Perhaps it would have an impact on amended claims in IPRs, but that seems like the biggest likely impact.”

I agree that the unpopularity of PGR would limit the practical impact of my strategy (this is also mentioned at the end of my letter). The goal would be for the Director’s bold actions to stimulate discussions and improvement for 101 in other contexts, like examination and litigation. In other words, the controversy and back-and-forth over the Director’s aggressive actions in PGR would stimulate (rather than force) improvements and reforms in other forums as well. The practical inconsistent and bifurcation would arguably motivate Congress to make everything uniform again.

David Boundy

November 18, 2020 09:49 amGreg @19 (also of interest to Kip) –

A refinement/replacement of mine.

Not so fast. Three problems.

First, the relevant statute (35 U.S.C. § 321) specifies that § 101 is fair ground for a PGR (though not an IPR § 311). The Director doesn’t have authority to create a carve-out.

Second, “void for vagueness” only applies to criminal statutes (or “civil penalty” statutes in which the state is on one side of the “v.”—civil penalty statutes are subject to many of the Constitutional protections as criminal, for this due process reason as well as others). “Void for vagueness” doesn’t apply to routine private sector economic regulatory statutes.

Third, the analogy to the “non-transitory” memo doesn’t extend here, for several reasons. The Director’s authority in ex parte matters is remarkably different than in inter partes matters. In ex parte matters, the Director can issue a memo to limit discretion of agency employees with no adverse effect on any member of the public. E.g., the “non-transitory” memo. In contrast, in an IPR/PGR, any change of the rules benefits one party and harms the other. Any time an agency proposes a rule that has downside for any member of the public, some provision of rulemaking law is triggered. So for IPR/PGR, it’s not as easy as a memo or administrative order or Trial Practice Guide or precedential decision.

3(b). The “non-transitory” memo was just an adoption or reminder of existing case law. In contrast, what you (and Kip) are proposing is to displace the law that arises from Congress and the courts. The Director doesn’t have that authority.

David

David Boundy

November 18, 2020 09:10 amGreg @19 –

Not so fast. Two problems.

First, the relevant statute (35 U.S.C. § 321) specifies that § 101 is fair ground for a PGR (though not an IPR § 311). The Director doesn’t have authority to create a carve-out.

Second, “void for vagueness” only applies to criminal statutes (or “civil penalty” statutes in which the state is on one side of the “v.”—civil penalty statutes are subject to many of the same Constitutional protections that apply to criminal, for this due process issue among others). “Void for vagueness” doesn’t apply to routine private sector economic regulatory statutes.

David

David Boundy

November 18, 2020 08:57 amKip —

To refine that a little bit,,,

Another weak link in the chain. An agency gets Chevron (or Auer) deference for its independent expert judgment in resolving ambiguity in statute (or regulation). Agencies don’t get deference for their interpretations of judicial precedent.

So the Director could issue regulations to pick-and-choose from among judicial precedent, as an exercise of “interpretative” authority of 5 U.S.C. § 553(b)(A), “housekeeping” authority under 5 U.S.C. § 301, or the “management supervision” power of 35 U.S.C. § 3(a)(2)(A). See Accardi v. Shaughnessy and Service v. Dulles. (The § 101 examiner guidance is valid and binding against examiners and the Board under this line of authority.)

But that interpretation would be an interpretative rule (with its asymmetric binding effect only against the agency and only in ex parte proceedings), not a Chevron-eligible interpretation that binds against any member of the public or the courts.

The outcome is “clear” once you understand all the constraints that operate. Else it’s — well, let’s refer to the lack of clarity you mention above as a “learning opportunity.” See the SSRN article linked above to take advantage of it.

David

Greg Aharonian

November 18, 2020 08:24 amIt is within the powers of the USPTO Director to issue an Administrative Order, under the Administrative Procedures Act, to all USPTO examiners and judges to NOT make use of 101 caselaw in any decision, by declaring that collectively, 101 caselaw violates Due Process Public Notice for being completely vague in being collectively completely contradictory. Kappos did something similar with his “non-transitory” memo in 2010 (sadly, too many patent lawyers and examiners ignored it). Currently, the USPTO violates the APA by allowing examiners to base rejections on the fatal vagueness of 101 caselaw.

The proof of this fatal vagueness is that there is not a single patent prosecutor who will guarantee (in terms of providing refunds) his or her clients that the patent claims they paid for will not be rejected under 101. No lawyer will guarantee that, because the caselaw (as explained in MPEP) offers no guidance to write claims that aren’t in violation of 101 caselaw. Is there anyone in this forum that will guarantee (with refunds) that the claims they write won’t be rejected under 101? No. So why tolerate the APA abuse of your clients?

This order would save hundreds of millions of dollars a year in Office Action responses, bring the patent system more in line with all of the Constitution, and eliminate 98% of the 101 woes of patent system users.

That leaves 101 problems in court cases. But for that, we all do is just start filing RICO lawsuits against any law firms that raise invalidity objections using the completely contradictory body of 101 caselaw.

In this way, we can all just collectively ignore the courts which for decades have refused to respect the inventors, the Constitution, science and engineering, with regard to “process” in 35 USC 101.

David Boundy

November 18, 2020 08:24 amKip —

Another weak link in the chain. An agency gets Chevron (or Auer) deference for its independent judgment in resolving ambiguity in statute (or regulation). Agencies don’t get deference for their interpretations of judicial precedent. So the Chevron link in your chain fails for another reason.

David

Anon

November 18, 2020 08:12 amMr. Boundy @ 15,

My postings to date have been aimed to establish a floor of understanding (rather than deconstructing any particular advancement of legal theory that may play out on that floor).

I would next advance along the line as provided by Mr. Doerre, in that I would ask Mr. Werking his view on what limits the particular words of “”establish” and “govern” mean IN the limited arena of Post Grant Review.

Does either ‘establishing’ or ‘governing’ give power to change fundamental aspects of patent law (as would be necessary to actually change the strictures of any of 35 USC 101, 102, 103 or 112)?

Mr. Werking?

(by the way, I would also disagree with you on the impact of the Tafas case – you might want to play a little more with the underlying holding of that case and view ‘facts as applied’ to be amenable to changing facts from one section of 35 USC et seq to another section of 35 USC et seq.)

J. Doerre

November 17, 2020 09:22 pmThe ultimate question for any regulation that the Director tries to enact under 35 U.S.C. § 326(4) is whether it falls under the grant of authority to “prescribe regulations … establishing and governing a post-grant review.” Labeling a rule as substantive or procedural does not automatically answer this question one way or the other.

Personally, I have a hard time with the argument that this provision authorizes the Director to prescribe regulations regarding what is or is not patent eligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

For one thing, the plain text of 35 U.S.C. § 101 is not ambiguous. The ambiguity is injected by an atextual, implicit judicial exception, but it is not clear that the Director has any authority to gapfill this implicit judicial exception.

I doubt that you are contending that the Director can *expand* the scope of patent eligible subject matter beyond the plain text scope of 35 U.S.C. § 101. It also seems odd to suggest that the Director can enact regulations that *contract* the scope of patent eligible subject matter to less than that specified by Congress in the plain scope of 35 U.S.C. § 101.

I guess you could consider the atextual judicial exception as having been implicitly incorporated by Congress into 35 U.S.C. § 101, at which point you could try to gapfill the ambiguiuty therein, but if the Court felt it necessary to graft an atextual, implicit exception onto a congressional statute, why would they not also feel it necessary to graft it onto an administrative regulation?

Moreover, the Director has already published guidance that is more generous than the approach taken in most courts and which purports to bind the Board. I guess I am not clear on what you evision: would you have him issue a regulation that is plainly contrary to Supreme Court precedent?

To what end? Challengers get to choose their venue. PGRs are not that common to begin with. The result would just be that no one files a PGR with a 101 challenge. Perhaps it would have an impact on amended claims in IPRs, but that seems like the biggest likely impact.

In the mean time, it would have no impact on initial examination at the Office, purporting to set up two different standards for application of § 101 at the Office itself.

David Boundy

November 17, 2020 08:33 pmCurious @ 2 and Anon @ 11 —

You’ve reached the same point that I have. § 316(a)(4)/§ 326(a)(4) gives the Director the duty to prescribe regulations to “govern” the proceeding. Which proceeding? The one specified § 311/§ 321, which call for adjudicating under the substantive statutes, § 101, § 102, § 103, and § 112, not something else cooked up by the Director.

The power to “govern” is not the power to redefine and override the substantive statute. Gap fill, yes. Create a private alternative, no.

Kip

November 17, 2020 03:23 pmAnon November 17, 2020 2:24 pm:

“As I understand your reply (and admit that I may be in error), ANY interpretive authority that you want to imbue (on such as 35 USC 101) would necessarily be constrained to cases IN post grant review.”

Yes. The USPTO is constrained by the statutory grants of power that Congress gave it. These grants of power are different between examination (35 USC 2) and PGR (35 USC 326). It might seem awkward and inconsistent that the Director has different levels of power between the two contexts, but Justice Breyer anticipated an essentially similar argument in Cuozzo: the Supreme Court held that the Director may create an inconsistency in claim construction between the USPTO and the courts because “the possibility of inconsistent results is inherent to Congress’ regulatory design.” 136 S.Ct. at 2146.

In other words, Justice Breyer was telling the patent bar that we should follow the statute, even if it leads to seemingly inconsistent results between two different forums or contexts.

Also, let me add that I am not sure that this strategy of mine would be successful. It has weaknesses, for all of the reasons you and others like David Boundy have pointed out. I simply think that it is worth trying, while Congress continues to fail to act and the patent bar struggles to apply section 101 with any predictability.

Kip

November 17, 2020 03:17 pmOne last point:

It’s worth mentioning that you’re citing a three judge supplemental opinion in Windy City to support your argument. The three judges were Prost, Plager, and O’Malley.

Two of those judges – Prost and O’Malley – signed the dissent that Justice Breyer flatly contradicted in Cuozzo.

And, in Windy Cities, the three judges cited one specific case, Cooper Techs, to argue that the Director does not have substantive rulemaking power. That is a case from 2008, a case interpreting 35 USC 2. As Justice Breyer wrote about Cooper Techs in Cuozzo:

“The dissenters, for example, point to cases in which the Circuit interpreted a grant of rulemaking authority in a different statute, § 2(b)(2)(A), as limited to procedural rules. See, e.g., Cooper Technologies Co. v. Dudas, 536 F.3d 1330, 1335 (C.A. Fed. 2008). These cases, however, as we just said, interpret a different statute. That statute does not clearly contain the Circuit’s claimed limitation, nor is its language the same as that of § 316(a)(4).”

Cuozzo, 136 S.Ct. at 2143.

The dicta in the supplemental opinion about Cooper Techs is not binding. And, even if it were, I would expect the SCOTUS to strike it down, based on what the SCOTUS unanimously held in Cuozzo about Cooper Techs.

David Boundy

November 17, 2020 02:53 pmSorry Kip, as I go back to read this again, there are so many errors…

To take one as an example, in your table, you ask “Is the question of the standard for claim construction a substantive rule that, if the Director is limited to procedural rulemaking, would violate the limitation?” Your box for “Cuozzo Original Panel Majority” is “Suggested No.”

In your table, you ask “Is the Director actually limited to merely procedural rulemaking powers in the context of the AIA?” Your box for “Cuozzo Original Panel Majority” is “Yes.”

Well, the decision itself is exactly the opposite, 778 F.3d 1271 at 1281-82 (citations omitted)—the Director’s authority is not so limited, and therefore “broadest reasonable interpretation is within the Director’s authority)—

§ 316 provides authority to the PTO to conduct rulemaking. … [T]he AIA granted new rulemaking authority to the PTO. Section 316(a)(2) provides that the PTO shall establish regulations “setting forth the standards for the showing of sufficient grounds to institute a review….” 35 U.S.C. § 316(a)(2). Section 316(a)(4) further provides the PTO with authority for “establishing and governing inter partes review under this chapter and the relationship of such review to other proceedings under this title.” Id. § 316(a)(4). These provisions expressly provide the PTO with authority to establish regulations setting the “standards” for instituting review and regulating IPR proceedings. The broadest reasonable interpretation standard affects both the PTO’s determination of whether to institute IPR proceedings and the proceedings after institution and is within the PTO’s authority under the statute.

The point you quote in your first block quote (beginning “We do not draw…”) confirms my point—the Director doesn’t have authority to rewrite §§ 101, 102, 103, 112 out of whole cloth. Where there are multiple standards (e.g., the choice between “broadest reasonable interpretation” vs. “ordinary meaning”) the Director does have authority (indeed a duty) to choose one from among those. In a next-over pigeonhole, the Director could disambiguate the Federal Circuit’s § 101 hash, by choosing one from among the Federal Circuit’s divergent standards (as the Director has done with his § 101 examination guidelines — that arises under the “Housekeeping Act,” 5 U.S.C. §?301, and “interpretative” rule authority of 5 U.S.C. §?553(b)(A).

But to make up an entirely different standard? No.

If there’s no rulemaking authority, then the PTO will never undertake rulemaking procedure. If either statutory authority or procedure fails, there’s no Chevron deference, as I explained at https://ipwatchdog.com/2019/10/09/re-examining-usptos-bid-adjudicatory-chevron-deference-response-one-analysis-facebook-v-windy-city/id=114364

Anon

November 17, 2020 02:24 pmKip,

As I understand your reply (and admit that I may be in error), ANY interpretive authority that you want to imbue (on such as 35 USC 101) would necessarily be constrained to cases IN post grant review.

In essence then, you are saying that the Director has power to set up a completely different system than the one he must use in a prosecution/pre-grant phase.

Do I have this (necessary) demarcation correct?

Kip

November 17, 2020 01:31 pmDavid –

Thanks for the reply.

I’m not sure why you think that I am arguing that Director has “all” rulemaking authority. That is not my view, and I agree with you that the Director does not have plenary powers to interpret section 101.

For example, the Director is arguably not allowed to interpret 101 in ordinary examination, because his powers in that context are limited according to 35 USC 2 (and CAFC case law).

To use your phrase, I agree with you that the Director has “some” substantive rulemaking authority. This includes deciding the standard for claim construction per Cuozzo. Arguably, this “some” power includes the power to “govern” through regulations, how PGRs proceed, including section 101 issues.

In other words, I agree with you that the Directors powers are limited and that he only has “some” new substantive powers in the AIA. Where we disagree is whether the power to interpret 101 is part of this “some.” You say that it is “clear” that this is not included in the “some.” I think it is far from clear. Everything that Justice Breyer wrote in Cuozzo leans in the opposite direction.

I’m not the only one to point this out. Several law professors agree.

David Boundy

November 17, 2020 01:18 pmKip —

I gave you essentially exactly this feedback first week of February. Your response was “I respectfully decline” to read it.

Cuozzo only discusses the difference between “none” and “some” substantive rulemaking authority. You’re trying to read Cuozzo as if it addressed the difference between “none” and “all.”

The dividing line is pretty clear in Cuozzo and subsequent Federal Circuit authority, if you read it with care and precision.

The reason it doesn’t work that way is that § 311) /§ 321 (after you chase through a couple indirects) only permit the PTAB to adjudicate under specific sections of “this title,” not some other §§ 101/102/103 created by the Director.

David

Kip

November 17, 2020 12:50 pmDavid Boundy:

One more point about Windy City:

1. You’re quoting from the supplemental opinion, which is arguably dicta, not the case itself, .

2. Even if three CAFC judges implicitly hold that the Director is limited to procedural rules, even in the AIA, this would not be the first time that the SCOTUS disagreed with the Federal Circuit.

Kip

November 17, 2020 12:47 pmReplies:

1. Anon: “How do you view the Tafas case, Mr. Werking?”

I view it as a pre-AIA case that has limited relevance to determining what the Director can do in PGR under the AIA.

2. @Curious:

“Assuming that the Director can has substantive rulemaking power under this statute — it is limited to inter partes review.”

As pointed out in the blog post and letter, the PGR statute uses parallel language to IPR (regulations “governing” these trials).

3. “Think of it. What happens if a new Director comes in and promulgates another set of rules that changes the standard for patent eligibility (for better or for worse)? Do we really want patent eligibility to hang on the whims of whomever is heading up the executive branch at the time? Also, why stop at patent eligibility? There are plenty of opportunities with regard to 102/103/112 to change the law as well. If we think the state of patent law is a quagmire now, imagine what it would be if 102/103/112 substantively changed every few years?”

You are arguing policy and the statute trumps policy. If Congress fails to implement the best policy, then we have to follow Congress and the statute, as interpreted by the SCOTUS, rather than rewrite the statute.

I agree with you that limiting the Director to procedure is good policy, reflected in 35 USC 2. That is not what Congress did with IPR/PGR, as interpreted by Justice Breyer.

Keep in mind that claim construction ALREADY oscillates when the politically-appointed Director changes. Iancu changes the standard of claim construction in response to Cuozzo, and his successor can change it back. Justice Breyer is clear in Cuozzo that such inconsistent results are part of Congress’s design (““the possibility of inconsistent results is inherent to Congress’ regulatory design” – 136 S.Ct. at 2146).

“Aside from the fact that it won’t work, it distracts attention away from the best approach to fix this problem — which is through Congress.”

I agree and would strongly prefer for Congress to step in, rather than the Director to use my strategy. Nevertheless, it’s been almost a decade and Congress continues to fail to do anything. Meanwhile, the Director can act today, and perhaps even stimulate Congress into action.

4. David Boundy:

I would have preferred to get this feedback before publishing (despite our frequent arguments, I respect your opinion and learn a lot from you).

That said:

“It’s called “Chevron.step zero.” The Director doesn’t have authority on this issue. That’s also explained in detail in my article at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3258694”

I believe Justice Breyer disagrees with you. Justice Breyer (joined by the unanimous SCOTUS) believes that the Director has the power to issue regulations “governing” IPR and PGR. And a regulation that interprets section 101 in PGR would govern PGR.

“It’s clear that no subsection of § 316(a) /§ 326(a) gives the Director authority to “interpret” § 101 in the way Kip posits.”

As clear as mud. 😉

“The Director’s substantive authority exists only where statute is ambiguous or silent.”

Both 35 USC 101 and 35 USC 326 are ambiguous and silent about how to apply the specifics and subtleties of modern patentable subject matter law, including SCOTUS creations like the abstract idea doctrine. Nobody thinks that section 101 is clear and unambiguous, in PGR trials or elsewhere. In fact, the massive ambiguity and unpredictability is the biggest complaint today about the U.S. patent system.

David Boundy

November 17, 2020 12:02 pmSecond half

The first big problem is that an IPR can’t raise § 101 issues. § 311(b) only permits §§ 102 and 103. § 101 can be raised in a PGR, § 321(b), but not an IPR. So I will shift the rest of this comment to IPR’s and the 32’s.

Second, § 326(a) does not grant of substantive rulemaking authority on the core substantive patentability issues of § 101, § 102, § 103, and § 112. The Federal Circuit recently reaffirmed that, Windy City. 973 F.3d at 1353.

The best argument is that the Director could by regulation put a collar on § 101 at institution phase under § 326(a)(2). As a parallel analogy, the recent “Applicant Admitted Prior Art” memo https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/signed_aapa_guidance_memo.pdf Let’s give this memo the benefit of doubt, and suppose that it interprets an ambiguity in a statute (but the AAPA guidance is invalid because ti was published as guidance—§ 326(a) requires regulation). I think § 326(a)(2) would permit the Director to do the same kind of exercise for § 101—sorting out the Federal Circuit’s conflicting morass into a consolidated uniform standard—and promulgate it as regulation. But that’s the high water mark of the Director’s substantive rulemaking authority.

The whole topic is explained in (too much) detail in my article, The PTAB Is Not an Article III Court, Part 3: Precedential and Informative Opinions at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3258694

Also—super basic—neither the Director nor the PTAB can ever earn Chevron deference for this kind of thing. Chevron deference can only apply where a tribunal acts within its rulemaking authority. It’s called “Chevron.step zero.” The Director doesn’t have authority on this issue. That’s also explained in detail in my article at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3258694

David Boundy

November 17, 2020 12:01 pmLooks like an earlier comment got lost, probably because it was too long. Split it in half.

This is an interesting view, but confuses some of the details, and ends up taking the applicable principles a little past the breaking point. I agree with Curious @2, “Oh, that way madness lies.” § 316(a)/§ 326(a) does grant the Director some substantive rulemaking authority, but only some. It’s not a blank check. § 316(a)(2)/§ 326(a)(2) gives the Director some authority to set standards applicable at institution, but I don’t see § 316(a)(4)/§ 326(a)(4) giving the authority that Kip posits. It’s clear that no subsection of § 316(a) /§ 326(a) gives the Director authority to “interpret” § 101 in the way Kip posits. The Director’s substantive authority exists only where statute is ambiguous or silent. This boundary on the Director’s authority was recently reaffirmed by the Federal Circuit in Facebok v Windy City. 973 F.3d 1321, 1353 (2020) (“The law has long been clear that the Director has no substantive rule making authority with respect to interpretations of the Patent Act.”)

Let’s look at the relevant statutes. § 316(a)(2) and (4) gives the Director the duty to prescribe regulations:

(2) setting forth the standards for the showing of sufficient grounds to institute a review under section 314(a);

(4) establishing and governing inter partes review under this chapter and the relationship of such review to other proceedings under this title;

Let’s take an example, Cuozzo. The important fact is that the choice of “broadest reasonable interpretation” vs. “ordinary meaning” is not specified in statute. Therefore Cuozzo holds, the PTO had authority to gap fill by regulation. The mistake that Cuozzo made in his briefs was to argue that the PTO had only “procedural” rulemaking authority, when statute had clearly supplemented that authority.

David Boundy

November 17, 2020 11:38 amAlso—super basic—neither the Director nor the PTAB can ever earn Chevron deference for this kind of thing. Chevron deference can only apply where a tribunal acts within its rulemaking authority. It’s called “Chevron.step zero.” The Director doesn’t have authority on this issue. That’s also explained in detail in my article at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3258694

David Boundy

November 17, 2020 11:33 amThis is an interesting view, but confuses some of the details, and ends up taking the applicable principles a little past the breaking point. § 316(a) does grant the Director some substantive rulemaking authority, but only some. It’s not a blank check. § 316(a)(2) gives the Director some authority to set standards applicable at institution, but I don’t see § 316(a)(4) giving the authority that Kip posits. It’s clear that no subsection of § 316(a) gives the Director authority to “interpret” § 101 in the way Kip posits. The Director’s substantive authority exists only where statute is ambiguous or silent. This boundary on the Director’s authority was recently reaffirmed by the Federal Circuit in Facebok v Windy City. 973 F.3d 1321, 1353 (2020) (“The law has long been clear that the Director has no substantive rule making authority with respect to interpretations of the Patent Act.”)

Let’s look at the relevant statutes. § 316(a)(2) and (4) gives the Director the duty to prescribe regulations:

(2) setting forth the standards for the showing of sufficient grounds to institute a review under section 314(a);

(4) establishing and governing inter partes review under this chapter and the relationship of such review to other proceedings under this title;

Let’s take an example, Cuozzo. The important fact is that the choice of “broadest reasonable interpretation” vs. “ordinary meaning” is not specified in statute. Therefore Cuozzo holds, the PTO had authority to gap fill by regulation. The mistake that Cuozzo made in his briefs was to argue that the PTO had only “procedural” rulemaking authority, when statute had clearly supplemented that authority.

§ 316(a) does not grant of substantive rulemaking authority on the core substantive patentability issues of § 101, § 102, § 103, and § 112. The Federal Circuit recently reaffirmed that, Windy City. 973 F.3d at 1353

The best argument is that the Director could by regulation put a collar on § 101 at institution phase under § 316(a)(2). As a parallel analogy, the recent “Applicant Admitted Prior Art” memo https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/signed_aapa_guidance_memo.pdf fairly interprets an ambiguity in a statute (but the AAPA guidance is invalid because ti was published as guidance—§ 316(a) requires regulation). I think § 316(a)(2) would permit the Director to do the same kind of exercise for § 101—sorting out the Federal Circuit’s conflicting morass into a consolidated uniform standard—and promulgate it as regulation. But that’s the high water mark of the Director’s substantive rulemaking authority.

The whole topic is explained in (too much) detail in my article, The PTAB Is Not an Article III Court, Part 3: Precedential and Informative Opinions at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3258694

Curious

November 17, 2020 11:24 amIn my view, the Supreme Court could hardly have been clearer.

Think about that statement for a second. The Supreme Court could hardly have been clearer? The Supreme Court is hardly ever clear — and the statement you cited is no different. Moreover, it does not support your position.

The fact that the Director is not limited to procedural rules implies naturally that the Director has some substantive rulemaking power. The Director can now advocate for substantive rulemaking authority that the Federal Circuit denied to his predecessors in the pre-AIA era.

The statute being interpreted was 35 USC 316 “Conduct of inter partes review.” Assuming that the Director can has substantive rulemaking power under this statute — it is limited to inter partes review.

I doubt any court is going to look upon this section as giving the Director a green light to make substantive rulemaking as to 35 USC 101 that will be given Chevron deference.

Think of it. What happens if a new Director comes in and promulgates another set of rules that changes the standard for patent eligibility (for better or for worse)? Do we really want patent eligibility to hang on the whims of whomever is heading up the executive branch at the time? Also, why stop at patent eligibility? There are plenty of opportunities with regard to 102/103/112 to change the law as well. If we think the state of patent law is a quagmire now, imagine what it would be if 102/103/112 substantively changed every few years?

I understand the desire to have a fix for the 35 USC 101 mess that we’ve gotten ourselves into. However, advocating for a fix such as what is proposed in this article is counterproductive. Aside from the fact that it won’t work, it distracts attention away from the best approach to fix this problem — which is through Congress. Congress is in the best position to produce a real and lasting fix. The Supreme Court isn’t going to admit they made a mistake and reverse Benson, Bilski, Mayo, Alice et al. Not that I have high hopes for Congress, but there are no better options.

Anon

November 17, 2020 10:42 amHow do you view the Tafas case, Mr. Werking?