“The results of the evaluation showed that INSPIRE was a useful resource that could save users time when approaching a new database or new feature…. However, the information was a top-level summary, it was not possible to drill down into specifics.”

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) launched their INSPIRE (Index of Specialized Patent Information Reports) “database of databases” on November 4, 2020. It provides useful summaries of patent databases to help both novice and expert patent searchers identify the most suitable search system. WIPO’s ultimate goal was to speed up the pace at which innovation takes place. To do this, INSPIRE identifies database features without commenting on any strengths or weaknesses of products. At the time of writing, INSPIRE listed 23 databases, both free and subscription. Content was still being added to the collection and there was scope for more sources to be included.

Huge strides have been made in the use of machine translation (MT) to enhance patent searches in the last decade. As inventors from Asian countries are so prolific in their patent filings, it is more important than ever to have access to patent specifications written in non-Latin character sets as well as Latin character sets. China became the top filer of international patents in 2019; Japan and the Republic of Korea were also in the top five countries.

Fig. 1 Illustration of Non-Latin characters for the term “search”

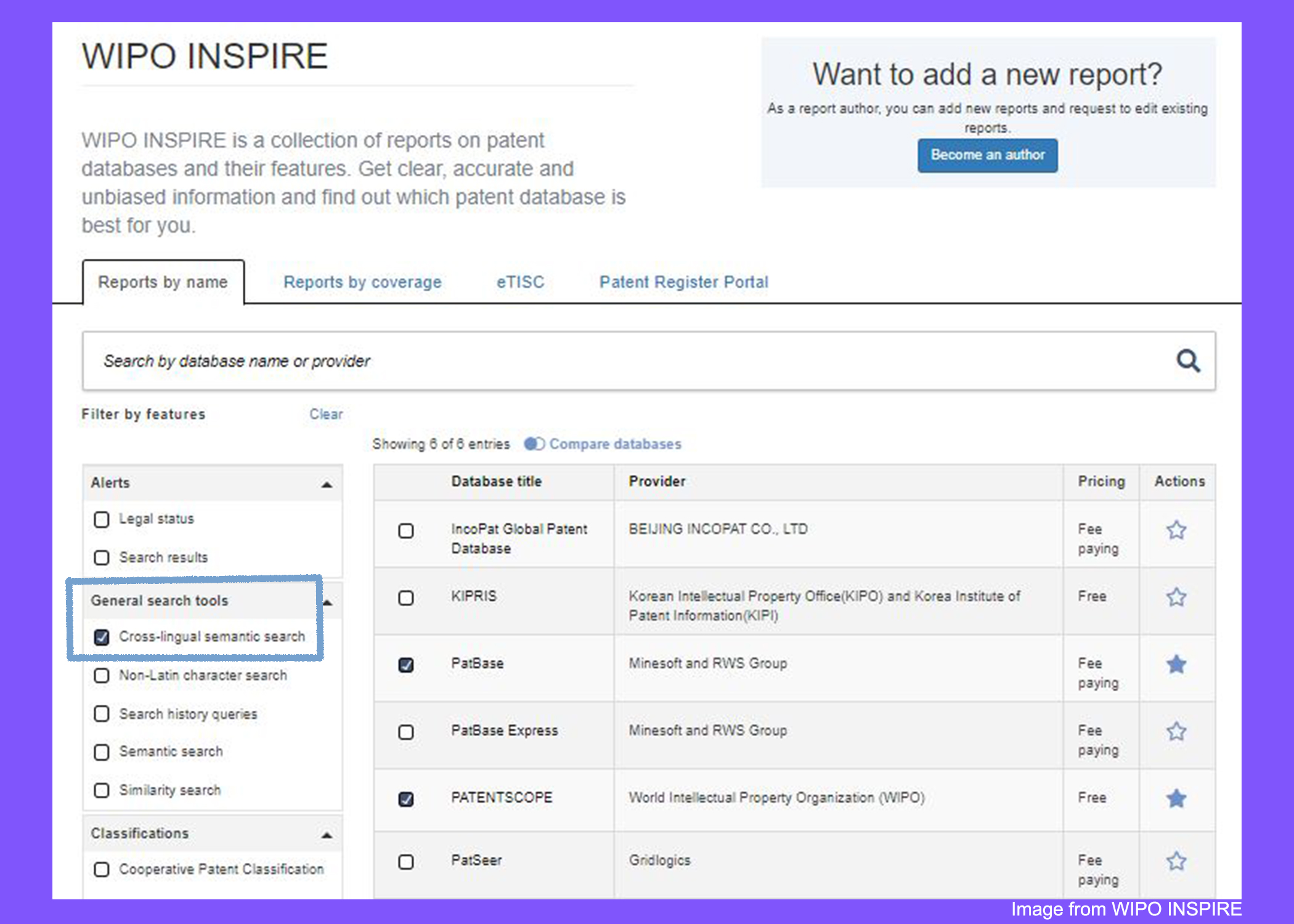

INSPIRE was used to look at sources that offered MT searches, in particular cross-lingual semantic search. Analysts chose two databases from INSPIRE. Based on inclusion of the cross-lingual semantic search feature, country coverage and availability of the source to the authors, PATENTSCOPE was selected as an example of a free source and PatBase as a fee-paying database. PATENTSCOPE is produced by WIPO and PatBase by Minesoft. Both platforms make use of Cross-Lingual Information Retrieval (CLIR) software, which retrieves information written in a language different from the language of the user’s query.

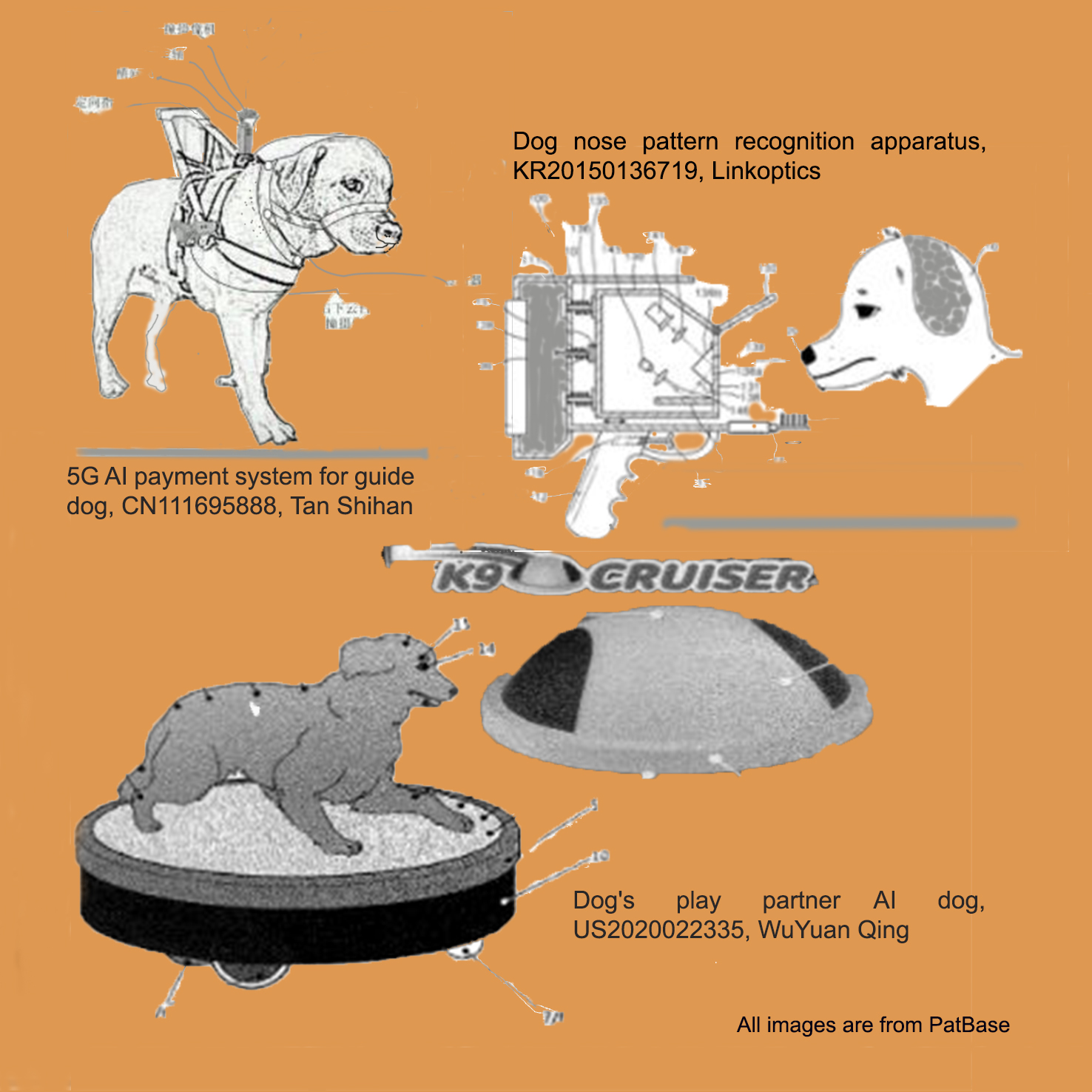

A patent study was conducted on artificial intelligence (AI) inventions concerning dogs, in order to investigate the two MT tools. The aim was to consider how the INSPIRE reports compared with hands on use of the two databases for this MT feature.

Patent Searches

Different types of patent search may be required during the patent lifecycle. See Akers. These can be a “state of the art” search conducted before research and development investment or a pre-filing novelty search conducted before applying for a patent. A further patentability search may be done before foreign filing, infringement searching before launch and validity searching at the time of grant. All searches require the correct balance between recall and precision. Searchers need to be skilled enough in their search strategy design in order that the search be broad enough to retrieve all documents that could be relevant, whilst not retrieving too many documents that could be irrelevant.

Machine Translation and Cross-Lingual Search

AI has led to great improvements in MT, including between patents in Latin and non-Latin character sets. Dwivedi and Chandra suggested that the most effective way to solve the problem of language barriers, could be through these three approaches:

- Document translation – machine translated full-text patents allow for search results to be to reviewed in the reader’s language, for example the European Patent Office’s (EPO’s) PatentTranslate and WIPO Translate.

- Query translation – MT can provide cross-lingual search, with synonyms and translations of keywords provided for several other languages, to broaden patent search strategies.

- Document and query translation approach

This study focused on query translation.

A previous analysis of multilingual searching by Kirch-Verfuss compared three databases including PATENTSCOPE and PatBase. He summarized the process involved in a cross-language search in which a multilingual search query was used on a multilingual text corpus.

CLIR in INSPIRE

There were two types of MT features shown in INSPIRE.

- Non-Latin character search translates one language, either Latin or non-Latin, into the required non-Latin equivalent.

- CLIR refers to the information retrieval activities in which the query or documents may appear in different languages. For example, a search strategy in one language can be converted into several other languages. The process is also known as translingual information retrieval or multilingual information retrieval.

This study focused on the second feature and analysts got the following results for cross-lingual semantic search from INSPIRE.

Fig. 2 WIPO INSPIRE search for databases with cross-lingual semantic search

Note – the blue stars in the Actions column on the right referred to databases for which content updates have been requested.

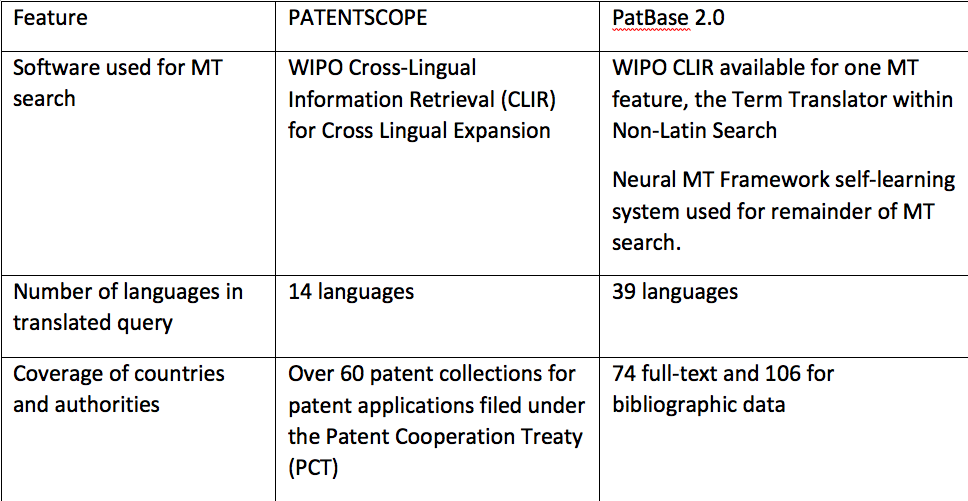

PatBase uses the WIPO CLIR application to power its Term Translator tool. In September 2020, PatBase 2.0’s simultaneous multiple language searching functionality was released. It allowed MT to be incorporated in the main search screen or search form and for terms to be searched simultaneously across native and multi-language machine translated full-text.

Table 1 – Summary of MT and countries covered in PATENTSCOPE and PatBase

Features of the two MT systems were investigated then results compared with the INSPIRE report.

Method

Analysts applied the MT tools for construction of search strategies in PATENTSCOPE and PatBase. They were used to find patents on AI concerning dogs and the following strategies were used:

- Set 1 included keywords for the concepts of “dogs” and “AI”, which were searched in the title, abstract and claims fields.

- Set 2 consisted of results from set 1 with the addition of a MT search for “dogs” and “AI”.

- Set 3 had any additional items from set 2 that were not in set 1.

All sets were limited to priority years greater than 2010 and with broad patent classifications for AI.

The study looked at the database best suited to particular tasks, in order to compare the outcome with the INSPIRE report.

Patent Examples on AI and Dogs

The searches retrieved patents on AI involving dogs, such as these examples.

Fig. 3 Examples of patents on AI involving dogs

Results of INSPIRE search

The INSPIRE database offered:

– a comparison of features for up to four patent databases

– more detailed information for individual sources of interest

– an interactive world database coverage map, which showed coverage of specific jurisdictions.

There was an option for users to send in suggested corrections and even to suggest additional sources.

The summaries were top-level and were not intended to provide as much data as a user manual. However, for this analysis more information would have been helpful. For example, there was no indication of whether the translation process was transparent. It was not clear whether the suggested keyword translations and synonyms could be checked for their meaning. The user might want to know whether changing precision settings would influence recall, for example whether the number of countries changed. There was no way to gauge whether the query would require editing and manipulation to get the translation to work. A searcher might want to know about the type of help offered if there were errors in their Boolean strategy. Experienced users might find the in-depth reports too brief and it would have been helpful to see a link to the database user guide. Maybe the form used for database comparisons could be clearer. For example, “language” refers to the interface languages for display and search.

The database was designed to offer independent, impartial data. Initially, vendors supplied the information for their own database entries, although patent information user groups have been asked for input. These groups include the Patent Information Users Group (PIUG), Confederacy of European Patent information User Groups (CEPIUG) and Patent Documentation Group (PDG). Therefore, at the time of the analysis, features such as ease of use were not covered.

The Actions option allowed users to choose their favourite sources then receive updates when a record was changed. At the time of writing, the whole record had to be reread, as there was no flag to show where the change had been made in the record.

Useful, but More Info Needed

The results of the evaluation showed that INSPIRE was a useful resource that could save users time when approaching a new database or new feature. Whether users were novices or experienced searchers, the tabular reports allowed selected sources to be compared at a glance. By opening individual database reports, slightly more detailed information was available from the vendor. However, the information was a top-level summary, it was not possible to drill down into specifics.

There was a similar comparison site called Intellogist some years ago. It gave opinions on databases from the searcher’s viewpoint rather than the producer’s. It would be interesting to review entries for PATENTSCOPE and PatBase after user groups such as the PIUG, CEPIUG and PDG have added their comments and assessments.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.