“When one seeks international patent rights it is typically wise to draft the application so it would be appropriate in both the United States and China [since these countries] have among the most stringent disclosure requirements (and getting ever stricter).”

For better or for worse, there is no such thing as a worldwide patent. There is, however, something that approximates a worldwide patent application that can ultimately result in a patent being obtained in over 150 countries around the world. This patent application is known as an international patent application, or simply an international application. The international treaty that authorizes the filing of this single international patent application is the Patent Cooperation Treaty, most commonly referred to as the PCT.

For better or for worse, there is no such thing as a worldwide patent. There is, however, something that approximates a worldwide patent application that can ultimately result in a patent being obtained in over 150 countries around the world. This patent application is known as an international patent application, or simply an international application. The international treaty that authorizes the filing of this single international patent application is the Patent Cooperation Treaty, most commonly referred to as the PCT.

The Streamlining Effect of International Patent Applications

For those new to the international stage, it may at first glance seem odd that it is possible to essentially file a single worldwide patent application, but not obtain a single worldwide patent. This is because patents are granted by individual countries, not by any international authority. There had been high hopes that this would change with the beginning of a unitary patent in the European Union, but BREXIT created a significant roadblock, as have constitutional challenges filed in Germany. The European Patent Office (EPO) does examine applications on behalf of member countries (with membership not being coextensive with the European Union) but actual recognition of the ultimate exclusive rights still comes from individual countries, although in many instances once the EPO has given an application a green light, the formalities are minimal—but the EPO process is another story for another day. Having said that, it is worth noting at this point that a PCT application can be filed with the EPO, and a filing in the EPO can claim priority to a previously filed PCT application.

In any case, the purpose of the international process of the PCT is to streamline as much of the common application procedures as possible while allowing applicants to file a single application that has the immediate potential to mature into a patent in over 150 countries.

The reality that individual countries issue patents doesn’t explain the rationale, and there is indeed a reason behind the rule. While the patent application process can be streamlined and uniform up to a certain point, as with the PCT process, individual countries have different patent laws, which makes a uniform, worldwide substantive patent granting process an impossibility (although through bi-lateral agreement patent offices in countries with similar laws will share work under various Patent Prosecution Highway agreements). Nevertheless, by way of example, in some parts of the world living organisms are not patentable at all, but in the United States at least some living organisms are patentable if they are the product of human engineering (i.e., genetically modified bacteria). Similarly, in much of the world computer software is patentable, but computer software has become increasingly difficult to patent in the United States thanks to the Supreme Court’s decision in Alice v. CLS Bank and decisions from the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit interpreting and implementing Alice.

The moral of the story is this: The protection ultimately received varies not only based on whether the country issuing the patent has a meaningful enforcement mechanism available to stop infringement, but also varies in kind depending upon whether a particular country will even grant a patent in the first place. When one seeks international patent rights it is typically wise to draft the application so it would be appropriate in both the United States and China. The United States and China have among the most stringent disclosure requirements (and getting ever stricter), and historically the United States also has the broadest interpretation of what is considered patentable subject matter, despite alarming creep in the wrong direction over the past decade by the United States Supreme Court.

The PCT and Member Countries

The PCT came into existence in 1970. It is open to States party to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (1883). The Treaty, like any other Treaty, is a legal agreement entered into between various countries. The purpose of the PCT is to streamline the initial filing process, making it easier and initially cheaper to file a patent application in a large number of countries.

In PCT speak, which can sometimes seem to be a language all its own, those countries that have ratified the PCT are referred to as Member Countries or Contracting States.

An international patent application can be filed pursuant to the rules of the PCT in any Member Country where at least one applicant is a resident or national. Upon the filing of the international application, it will be effectively treated as a patent application in all of those Member Countries that have ratified the PCT. Countries that are not members of the PCT include (in alphabetical order): Afghanistan, Argentina, Bolivia, Congo, Ethiopia, Guyana, Iraq, Pakistan, Paraguay, Somalia, South Sudan, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Yemen. The one country from this list that often surprises people, and where you may find clients wishing the PCT applied, is Argentina.

The International Patent Application Process

The appeal of the PCT process is that it enables patent applicants to file a single patent application and have that single, uniform patent application be treated as an initial application for a patent in any Member Country. It is, however, important to understand that obtaining international patent protection is not cheap. It is also important to understand that the international patent application you file will not mature into an international patent.

The PCT procedure consists of two main phases. As mentioned, the first phase begins with the filing of an international application. The second phase begins upon entering into the national stage in any number of countries, which starts evaluation under the domestic patent laws in each particular country. Thus, there is said to be an international phase and a national phase to the PCT process.

Direct Domestic Filing vs. International Filing

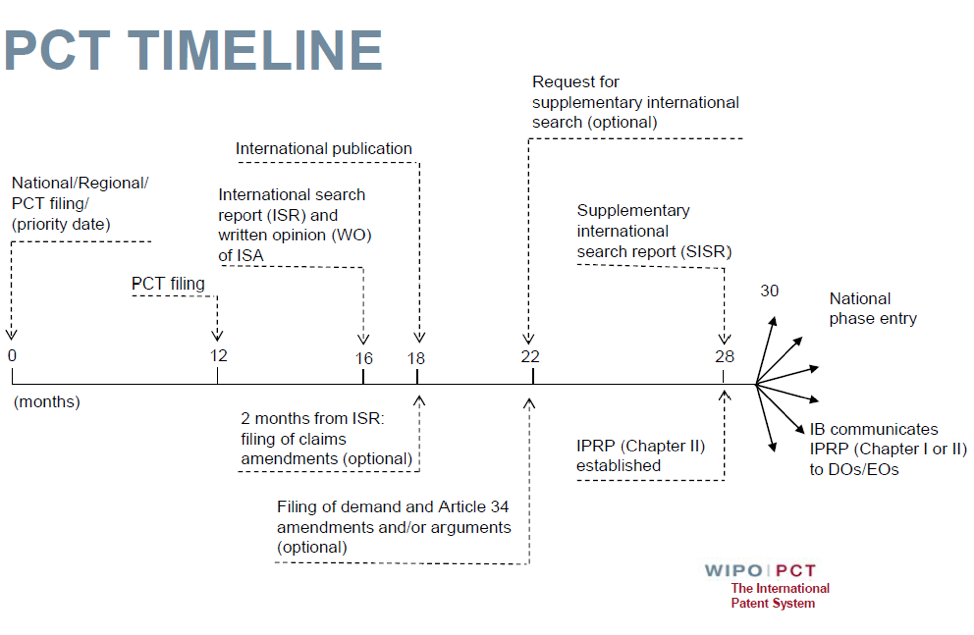

The first option many inventors and businesses pursue is to file the first patent application on an innovation in the country where they are physically located. This is shown as the starting point of the PCT timeline below, courtesy of WIPO via the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

This direct domestic filing option is accomplished pursuant to the national laws and regulations of whatever country in which the application is filed. A U.S. patent application, such as a provisional patent application filed under 35 U.S.C. 111(b) or a non-provisional patent application filed under 35 U.S.C. 111(a), is a direct filing option. From the U.S. perspective, a filing in a patent office other than the USPTO that is not filed pursuant to the PCT is considered a foreign application. Direct U.S. patent applications and foreign patent applications are distinguished from an international patent application, which can be filed in any receiving office around the world.

If an applicant files either a U.S. patent application or a foreign patent application, they can still file an international patent application pursuant to the PCT within 12 months of the earliest filing date. If the applicant files an international patent application within 12 months of the earliest filing date (whether a U.S. application or foreign application) then the international patent application may be given priority all the way back to the filing date of that first filing (assuming you claim benefit of that first filing, which you should as a general if not absolute rule). What this means is that when an application ultimately gets examined substantively it will be considered to have been filed as of the earliest filing date, which further means that anything that happens (i.e., public sale, public use, publication, disclosure) after that date cannot be prior art. Having an early priority date is critical in many cases because without capturing and holding that early date prior art the applicant will find it impossible to obtain patent protection in many (if not all) jurisdictions.

Because the earlier filing of a U.S. patent application or a foreign patent application can be used to establish priority for a later filed international patent application that will seek rights in multiple countries, many inventors and small businesses just start with a U.S. patent application. The filing costs are less by just pursuing a U.S. patent application from the start, and you have 12 months to decide if you really want to pursue foreign rights. Indeed, a provisional patent application can be used to establish priority, but as with any application that will be used for priority the completeness and detail of the application is of paramount importance. Many provisional patent applications provide thin disclosures (to be generous) since they are not examined. It is crucial to always understand that you can only obtain priority with respect to what has been adequately described, which means appropriate technical details. Best practices are to always include a claim at the time of filing when a filing will be (or may be) used outside the United States to establish priority.

What is a Receiving Office?

Whether filed initially or sometime on or before the expiration of 12 months from the priority filing, the international application must be filed in an authorized Receiving Office. The Receiving Office functions as the filing and formalities review organization for international applications. But that still begs the question: What is a Receiving Office?

The patent offices of the countries that are members to the PCT are called Receiving Offices. You cannot simply file an international patent application in any patent office, but rather you need to file in the appropriate Receiving Office. Where there are several applicants who are not all nationals and/or residents of the same country, any Receiving Office where at least one of the applicants is a resident or national is authorized to receive an international application filed by those applicants. Alternatively, the international application may be filed with the International Bureau as the Receiving Office. In the United States, the USPTO acts as a Receiving Office for United States residents and nationals, but the International Bureau of the World Intellectual Property Organization may also act as a Receiving Office for U.S. residents and nationals.

It is worth noting that the rule requiring filing in an authorized Receiving Office written in mandatory terms, but if an error is made and the wrong Receiving Office is used the application will be forwarded to the International Bureau for proper processing provided that at least one applicant is a resident or national of a Member State and the application is filed in a language acceptable to the International Bureau.

Foreign Filing License Requirement

Applicants need to know that if the invention was conceived of in the U.S. it will be necessary to obtain a foreign filing license before filing a patent application outside the U.S. If a patent application is filed in the U.S. (as discussed previously) an implicit requested a foreign filing license has been made, and ordinarily one will be automatically granted in the filing receipt. If a foreign filing license is not granted explicitly in the filing receipt, individuals at the Pentagon (or perhaps some other government agency) are reviewing the application to determine whether it raises a matter of national security warranting the imposing of a secrecy order. Secrecy orders are quite rare, but an application cannot be filed overseas without a foreign filing license. If one is not granted explicitly one is acquired through the passage of 6 months by operation of law. Thus, if a secrecy order will be imposed it will be issued within 6 months of the filing date of the application. And, of course, to completely undo the requirement for a foreign filing license, one can be obtained retroactively.

A foreign filing license is not required to file an international application in the United States Receiving Office but may be required before the applicant or the U.S. Receiving Office can forward a copy of the international application to a foreign patent office, the International Bureau or other foreign authority. So how then can one file directly with the International Bureau as the Receiving Office? If no corresponding national or international application has been filed in the United States that would provoke the granting of a foreign filing license and you want to use the International Bureau as the Receiving Office and the invention was conceived in the United States, a petition for a foreign filing license under 37 C.F.R. 5.13 must be filed. A petition for license should be in letter form and must include the fee, the petitioner’s address, and full instructions for delivery of the requested license when it is to be delivered to other than the petitioner and must also be accompanied by a legible copy of the material upon which a license is desired.

The National Stage

Whether you use an earlier filed patent application to support priority for the filing of the PCT Application (as discussed previously), or you file an international application without any priority claim, you will ultimately need to enter into what is called the national phase in every country where you wish to ultimately obtain a patent.

If you file an international application first, you have 30 months from the filing date of the international application within which to enter the national phase in any countries you wish. If you file an earlier application that will be used to establish priority for the international application you will have 30 months from the filing of that earlier application within which to enter the national phase in countries where you wish to obtain a patent. Regardless, at the this point of entry into the national phase things can get extremely expensive because you would have to pay national fees to each country, and you would have to obtain translations into the language of each country where you wish to proceed. Your primary patent attorneys can and usually do coordinate international prosecution, but they cannot represent you in countries where they are not admitted to practice, which means you will need separate representation in every country where you want to obtain a patent.

For more information on entry into the U.S. national stage pursuant to 35 U.S.C. 371. see MPEP 1893.

UPDATED February 7 @ 3:50 pm EST to clarify that you have 30 months to enter the national stage from the priority date.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Vector ID:6675611

Copyright:Vitalius

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Enhance-2-IPWatchdog-Ad-2499x833-2.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

4 comments so far.

Cy Bates

February 8, 2021 09:35 amI retract my earlier question. After reading the paragraph again and I realize I misread it the first time. It is stated correctly and is consistent.

MaxDrei

February 7, 2021 06:02 amMr Bates: Good question. Confirmed. Here:

https://www.wipo.int/pct/en/texts/time_limits.html

from the WIPO web-site.

Mr Quinn might want to clarify further. After all, if (for example) one files one’s earliest patent application at the USPTO, then discloses the invention, then files a PCT (including a Paris Convention declaration of priority of the earlier-filed US application ) and 30 months after filing that PCT attempts to enter the national phase, you are very likely to suffer disappointment, and perhaps much worse.

Cy Bates

February 6, 2021 08:03 pmArticle says national stage must be entered by 30 months from the filing date of the international application, but the timeline chart appears to show that it is 30 months from the priority date. I believe it is 30 months from priority date. Can I get a confirmation?

ipguy

February 3, 2021 02:59 pmWhen dealing with China, you have to be very careful that things, quite literally, do not get lost in translation. Also, give numerous specific examples when you use a generic term because if you give only a single example, the China Examiner is going to demand that the applicant replace the generic term with that specific example since no other examples were given.