“Jefferson’s letter to [Isaac] McPherson showed that he weighed the marginal contribution of an invention against basic, foundational technologies, keeping in mind that a mere change of form—like changing fashions—should not be patentable.”

You cannot get a patent for an invention if it would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time. This is as true today as it was at the founding of our nation. The reason for this rule is clear—the obviousness-bar is necessary to balance rewarding innovation with free and fair competition. The Supreme Court has observed, alluding to the Constitution’s authorization for federal patents, “[w]ere it otherwise, patents might stifle, rather than promote, the progress of useful arts.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 427 (2007).

You cannot get a patent for an invention if it would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time. This is as true today as it was at the founding of our nation. The reason for this rule is clear—the obviousness-bar is necessary to balance rewarding innovation with free and fair competition. The Supreme Court has observed, alluding to the Constitution’s authorization for federal patents, “[w]ere it otherwise, patents might stifle, rather than promote, the progress of useful arts.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 427 (2007).

Achieving Balance

While we all agree that obvious inventions should not be patented, the devil is in the details on how to draw that line between the obvious and the nonobvious. Through experience and “slow progress” courts and practitioners have advanced the delicate art of obviousness argumentation. Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City, 383 U.S. 1, 10 (1966). All the while, the Supreme Court has cautioned, as it did in KSR, that the doctrine of obviousness “must not be confined within a test or formulation too constrained [or rigid] to serve its purposes.”

Today it seems that the courts, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and the bar have found sound, flexible ways to ensure free and fair competition within the useful arts of software and chemistry. The Supreme Court’s omnipresent precedent in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, though controversial, ensures that abstract ideas—the basic building blocks of science—are not monopolized, especially through software or business method patents. And drawing inspiration from the Supreme Court’s demand in KSR for flexibility in obviousness, the USPTO has given its examiners extensive guidance and frameworks that are particularly useful for applying the doctrine of obviousness to chemical inventions. These frameworks enable flexibility in considering patent applications directed to new combinations of chemical ingredients, changing proportions in solutions, and even alterations in ingredients’ molecular structure. Instead, here, I will focus on the obviousness of mechanical inventions.

Getting Crowded

To be sure, the law of obviousness is routinely applied to mechanical inventions, as with all others. The USPTO has provided its examiners with guidance to allow rejection of inventors’ assertions of innovation through choice of materials or simple rearrangement or elimination of parts of known devices. Still, I have witnessed an overabundant proliferation of patenting in some mechanical fields. For some types of simple mechanical devices, there seem to arise vast thickets of patents. Canny practitioners have been successful in writing patent claims that distinguish their inventions over other mechanical devices by employing detailed descriptions of parts—a “flange” here, a “member” there – in which very slight structural differences become all-important “elements” of claims. Never mind that they are all slightly different arrangements to accomplish something well-known; the patent attorney will argue, “show me why this or that physical ‘element’ was known or obvious.” These arguments often prove successful at the USPTO or in court, leading to more and more crowding of the “art” in a given field and iteratively hemming in the competition and prospective manufacturing newcomers alike.

A Revealing Letter

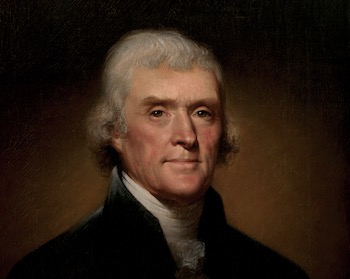

When I encounter these thickets of mechanical device patents, I often benefit from going back to first principles, the founding era of America’s patent laws, and Thomas Jefferson. After ratification of the Constitution in 1789, the first Congress enacted the nation’s first Patent Act in 1790. Patents applications were to be considered by the “Commissioners for the Promotion of Useful Arts” (a proto-Patent Office), who originally were to be designated by the Secretary of State, the Secretary of War, and the Attorney General (Graham). As George Washington’s Secretary of State, Jefferson became this commission’s “moving spirit” and the “first administrator of our patent system.”

Years later, after serving under Washington and completing his own presidential administration, Jefferson wrote a letter about patents to Isaac McPherson in 1813. This letter has become historically famous, mostly for Jefferson’s more lofty discussion of intellectual property. Quotations from this letter are almost universally from Jefferson’s so-called “fire metaphor” and his observation that an invention must be significant to be “worth to the public the embarrassment of an exclusive patent.” But it is also interesting to consider the particular occasion and circumstances of the letter itself for its bearing on mechanical patents.

Isaac McPherson had originally written to Jefferson because a notorious inventor named Oliver Evans was threatening to sue him on his patents for “Elevators, Conveyers, and Hopper-boys.” When the Patent Act was passed, Evans was one of the first in the country to apply for and receive patents from Washington’s cabinet (Jefferson, along with Henry Knox and Edmund Randolph). As President, Jefferson himself had signed a law reviving and extending the term of some of Evans’ patents. Later, Evans’ agents traversed the country demanding royalties from perceived infringers. One of these agents even visited Jefferson, making the accusation that his agricultural equipment at Monticello infringed on Evans’ patents. Jefferson settled for Evans’ “moderate patent price,” but McPherson was seeking Jefferson’s advice on how to put up a fight against Evans’ claims.

In the letter, Jefferson gave McPherson a detailed explanation for why he thought some of Evans’ later patents were invalid. Jefferson believed that Evans’ grain elevator invention was obvious, based on “simple machinery [that] has been in use from time immemorial.” He discussed the similarities of Evans’ device with basic water-bucket elevators used for wells going back to the time of Rome, Archimedes’ screw pump, and a device called the “Persian wheel,” which was known from Egypt and the Barbary coast since 1727. He also discussed some textbooks and colonial prior art from Virginia farmers, including a machine that he himself had used for a long time for “Benni seed…Indian corn, and…wheat.” Jefferson believed these examples ought to “flash conviction both on reason and the senses, that there is nothing new in [Evans’] elevators.”

Jefferson told McPherson that, even if there were some structural distinctions between Evans’ invention and the prior art, that should not entitle him to a patent. In Jefferson’s opinion, “a mere change of form should give no right to a patent. [A]s a high quartered shoe, instead of a low one, a round hat, instead of three square, or a square bucket instead of a round one. But for this rule, all the changes of fashion in dress would have been under the tax of patentees.”

McPherson used Jefferson’s letter and other aspects of his investigation to petition Congress to cancel Evans’ patent. He submitted to Congress a report entitled “Memorial to the Congress of Sundry Citizens of the United States, Praying Relief from the Oppressive Operations of Oliver Evans’ Patent.” Congress ultimately did not act on it, but I find Jefferson’s advice remains helpful today.

Let’s Avoid Future Nuisances

Jefferson’s letter to McPherson showed that he weighed the marginal contribution of an invention against basic, foundational technologies, keeping in mind that a mere change of form—like changing fashions—should not be patentable. Applying this flexible approach to obviousness in the area of mechanical inventions might prevent patent thickets and enable fair competition, lower barriers to entry, and decrease prices. Otherwise, the mechanical patents of today have the potential to raise nuisances similar to the software patents so ubiquitously sued upon.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

21 comments so far.

ipguy

March 9, 2021 05:31 pm@17 “why are they not simply waving everything through”

That would be terribly indiscreet.

Anon

March 9, 2021 03:39 pmJohn,

Your comment about any type of “horizontal” is quite meaningless and besides the point. Horizontal, vertical or diagonal, the premise remains the same and remains fully applicable.

It is ONLY a supposition — your supposition — on relative value that appears to be the reason why you would even try to treat the plain cold hard facts differently. Sorry, but no. Such “value” judgements are not up to you. Further, having studied innovation my entire career, from having careers in engineering, management and law, I would put to you that your “values” do not reflect the reality of either why we have innovation protection laws in the first place, nor on the real-world effects of having such laws.

You should know well enough that larger established corporations would love to compete on those factors for which they have advantages, and simply are NOT in the practice of promoting innovation for innovation’s sake. IF they could get away with stifling innovation, they surely will.

Efficient Infringement is very very real – and very much a Rational Actor model. Neither of these truths affect the true value of innovation, albeit they certainly affect the bottom line of those that would practice Efficient Infringement.

Reminder: those that coined the term “Patent Troll” and used that term as a weapon of propaganda were looking out ONLY for themselves. Not you, not me, not the common man, and certainly not for the sake of innovation or the reason why THIS SOVEREIGN has adopted innovation protection laws.

Onward and upward indeed – just not how you are thinking.

John

March 9, 2021 10:30 am@12, 14, and 15: The assumption seems to be that innovation is primarily “horizontal”, i.e., innovating alternatives. Certainly, that has some value. But not nearly as much value as price competition and vertical innovation, i.e., innovating improvements that build on what came before. Patent prosecutors tend to be obsessed with design arounds rather than competition and improvements. Onward and upward, I say.

@5–It seems that you want it both ways. Ancient insights from 1776 are too old to be valuable. While recent legal developments (Alice) are likewise worthless in your view. It does not look like the real critque here is historical timing, but rather your policy preferences which seemed to me to have had their hayday in the 1990s and early 2000s. It is good that the 1998 standard of useful, concrete, and tangible results is gone.

@13–It is a straightforward historical insight about change of form. But since that is the main upshot of one of the most famous letters on patent law written by our country’s first head of its proto-patent office, it does not seem worthless, especially when brought forward to perceived problems of the present day. It also seems to have sparked a rather lively debate and hit on a fundamental divide, which is fantastic and enjoyable.

Anon

March 9, 2021 07:46 amMaxDrie,

Your disconnect with the way things are in the US is beyond alarming.

MaxDrei

March 9, 2021 04:39 amipguy, can you (or maybe 6) enlarge on that comment, please. If Primaries face no adverse consequences when they are reversed by the PTAB, why are they not simply waving everything through, thereby to i) make their production figures look good, and ii) minimise levels of stress during their dialogue with Applicants and their attorneys?

ipguy

March 8, 2021 09:31 pm@6 “submitting to bullying by patent attorneys.”

Based on my experience, 99% of the time the bullying flows in the opposite direction, especially from Primary Examiners who consider themselves accountable to no one.

Until the day comes when Examiners (and their supervisors) face financial/production consequences from being overruled by the PTAB, the arrogance and abuse of authority will continue. To this day, Examiners know that they can “wait out” just about any applicant.

Curious

March 8, 2021 01:25 pmIn either case, you become part of the strong innovation system either by dutifully rewarding those who innovated earlier than you, or you take the initiative and become an innovator.

Bingo … the progress of science and the useful arts is promoted by both (i) rewarding the original inventor and (ii) encouraging others to innovate around the original invention.

Anon

March 8, 2021 11:07 amLet me amplify a view expressed by Night Writer.

If you find yourself ‘hemmed in,’ than you should rejoice that your field has attracted the level of attention that it has and that OTHER people are busy innovating.

The maxim “Necessity is the mother of invention” is applicable.

So stop the whining, recognize that one ALWAYS has a choice of paying the dues to those others that innovated before you came on the scene,…

… OR

get busy and innovate yourself.

In either case, you become part of the strong innovation system either by dutifully rewarding those who innovated earlier than you, or you take the initiative and become an innovator.

MaxDrei

March 8, 2021 10:16 amIf I see it right, what Jefferson offered on the subject of patentability is nothing more than that “a mere change of form” ought not to be enough.

Hardly the most incisive thought on the subject is it (even assuming he meant utility patents and not design patents). Is this the best we can do, for inventors and for those assessing the validity of the patents of others?

I note that the author of the piece is a patent litigator. Does this article accurately reflect the depth of analysis which litigators put into the obviousness issue, these days?

I’m asking myself why Gene thought the piece worth publishing. What does it bring? What am I missing?

Night Writer

March 8, 2021 08:50 amThis post is such crxp. Anyone that actually does real innovation knows it today’s world it is almost impossible to protect an invention. There are so many design arounds that a clever person can think. Just give me a claim or 10,000 claims and I can figure out a design around. Morever, IPRs insure there is little leverage to stop anyone from practicing your invention.

Moreover, the test under KSR is not law. It is equity where a fact finder can find or not find that the invention obvious no matter what the facts. All of these multi-factored tests mean no law but that fact finder can do whatever they want.

Please give a few real examples where you believe you are “hemmed in”. And what does even mean? Like, gee, I would like to copy what they did but they have a patent and I am not going to hire anyone to innovate so this patent system sxcks?

>>These arguments often prove successful at the USPTO or in court, leading to more and more crowding of the “art” in a given field and iteratively hemming in the competition and prospective manufacturing newcomers alike.

AAA JJ

March 7, 2021 04:57 pmI think we should give Jefferson’s views on the “obviousness of mechanical inventions” the same consideration we give to his views on “all men are created equal.” Which is to say: none.

Pro Say

March 6, 2021 04:41 pm“Balance” (like so-called “eligibility compromise”) . . . is nothing more . . . than a nonce word . . . for . . . “No patent for you!”

Paul Cole

March 6, 2021 12:46 pmReaders will probably be aware that the Oliver Evans patents came before the Supreme Court in Evans v Eaton in 1818 and 1822 and he will be remembered as a distinguished American inventor, not least for his later work on steam engines and locomotives. An example of his automated milling system was purchased by George Washington for Mount Vernon is still in working operation to this day.

Mark Pope

March 6, 2021 12:20 pmHow can you bully someone who has power over you?

Anon

March 5, 2021 05:57 pmBenny,

I would put zero stock in trying to align your views with this author.

Benny

March 5, 2021 03:42 pm“Still, I have witnessed an overabundant proliferation of patenting in some mechanical fields.”

So have I, John, so have I. It has reached the ridiculous, with examiners ignoring prior art staring them in the face, and submitting to bullying by patent attorneys.

David Lewis

March 5, 2021 01:56 pmIt seems to me that just as technology progresses, the science of law making laws and what laws should and should not be does also. Fortunately, in the 20th century we no longer follow Hammurabi’s codes literally. Since Jefferson, there has been new legislation, which presumably was intended to fix problems with earlier laws. We cannot keep our laws frozen in time period of 1776, because things have changed quite a bit since then. Alice, likewise has created havoc in our legal system as have many other developments in recent times, encouraging the infringement of patent owners patent rights, and the problems should be fixed. While there is a balance to be struck between the patent owner rights and the rights of those that want to infringe on other’s inventions, it seems to me that we are in an infringers paradise at the moment (or at least going in that direction), which is not ultimately in the public interest.

Josh Malone

March 5, 2021 01:30 pm@Paul – Zorina Khan in Democratizing Invention emphasizes that the American system of the 19th century rewarded incremental everyday inventions which tapped into the ingenuity of ordinary citizens. Housewives, factory workers, school teachers – individuals from all walks of life and all levels of education contributed to the marvel of a fledgling colony rising to become a world superpower within a few generations.

This history should guide Congress and the USPTO on their renewed push for expanding participation by women and minorities. Our founders had figure it out by 1790 as they offered a property right to “any person…setting forth, that he, she, or they, hath or have invented or discovered any useful art, manufacture, engine, machine, or device.”

Anon

March 5, 2021 01:20 pmIt is pure legal error to put so much weight on the Jefferson McPherson letter.

Rule of Law versus Rule of Man.

Timing.

the fact that so many who harbor anti-patent views cling so strongly to that one letter.

PAUL V MORINVILLE

March 5, 2021 10:34 amWhy does it matter if the invention is on the margins? If it’s value to the more important inventions is also marginal, competitors are not likely to incorporate it..

Also, it very likely can be designed around and may never be enforced because the value of the infringement is lower that the cost of litigation..

A patent thicket is really an invention thicket. It has value in protecting incremental improvements. Most incremental improvements have no value, but every once in a while one of those improvement matters.

Edison did not invent the light bulb. He invented a carbon impregnated filament that lasted long enough to make a light bulb commercially viable.

Amazon’s One Click patent distinguished Amazon from the competition giving them an edge.

The premise that marginal inventions and patent thickets are bad is a false premise.

PAUL V MORINVILLE

March 5, 2021 10:23 amAfter Eli Whitney had lost dozens of cases in GA because 2 witnesses claimed to have seen the cotton gin in operation 5 years prior in England, a GA Judge finally found for Whitney saying that the cotton gin had exploded into use within a single year in the US and it should have done the same in England but didn’t and therefore he didn’t find the witness testimony credible. I think this may have been the first decision that used turning a market to overcome an invalidity market.