“Computer-implemented simulations are as patentable as any other computer-implemented method. Nothing is to be changed in the patentability assessment criteria utilized so far, with the clarification that technicality of the simulated system or model does not necessarily impact on patentability.”

The Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office (EPO) recently published its decision No. G1/19 on patentability of simulations.

The Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office (EPO) recently published its decision No. G1/19 on patentability of simulations.

There was great anticipation for such a decision, after landmark decisions 641/00 (COMVIK) and G3/08, mainly due to the ambiguous formulations of the questions of law to the Enlarged Board of Appeal. The result is “business as usual”, but several clarifications might be useful in the future.

In the following, we first summarize the questions of law, the clarifications of the Enlarged Board of Appeal and then infer possible consequences for applicants and practitioners.

Questions of Law

By interlocutory decision T 489/14 (22 February 2019), Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.07 (referring Board) referred the following questions of law to the Enlarged Board of Appeal for decision:

- In the assessment of inventive step, can the computer-implemented simulation of a technical system or process solve a technical problem by producing a technical effect which goes beyond the simulation’s implementation on a computer, if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as such?

- [2A] If the answer to the first question is yes, what are the relevant criteria for assessing whether a computer-implemented simulation claimed as such solves a technical problem? [2B] In particular, is it a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, at least in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process?

- What are the answers to the first and second questions if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as part of a design process, in particular for verifying a design?

As many practitioners noted, in question 1 “computer-implemented simulation as such” was a definition that came out of the blue with respect to (case) law. In fact, the question could simply boil down to asking whether or not the term “simulation” could replace the term “method”.

Once a “method” can be implicitly understood behind the “simulation”, part 2A of the second question would not be meaningful, as criteria for patentability of computer-implemented methods are well established and quite stable (i.e. predictable) at the EPO.

However, question 2B was interesting, owing to the fact that technicality of the underlying phenomena of a simulation were drawn into the discussion, and raised concerns about the fact that related considerations by the Enlarged Board of Appeal could entail serious consequences for the standard practice.

Finally, claiming a final design (or actual production) step in a computer-implemented method could have only been beneficial to patentability, due to tying the computer-implemented method to a physical reality, and this was remarked on by several amicus curiae briefs filed with the Board, which did not expand very much on the third question.

Reasoning and Clarifications by the Enlarged Board of Appeal

From the beginning of its long and articulated reasoning, the Board made it clear that there was no reason to depart from the approach of the above COMVIK decision (confirmed by G3/08) and all of the received questions related to patentability (i.e. novelty, inventive step, industrial applicability) and not to eligibility (non-inventions), as the referring board recognized the presence of technical character in the claims presented in the case. Assessing technical character is recognized as an intermediate step between eligibility and patentability, and surely a key one, given that today the mere presence of a computer renders a claim eligible, and the obviousness is compelled to be strictly tied to the specific invention and related prior art.

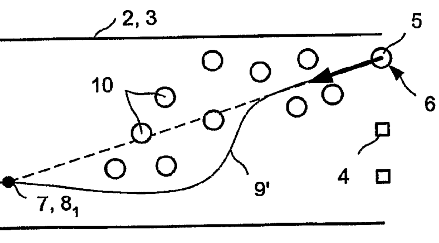

The original claim in the case, in fact, was directed to “A method of simulating movement of an autonomous entity through an environment” and the application makes it clear that this is for the purpose of designing a building that would enable a crowd to flow efficiently through its spaces:

The main claim specified apparently subjective concepts such as personal profile, preferred step, neighborhood, and obstacles. The referring Board tended to consider such an original claim deprived of technical purpose.

However, the Applicant changed its main request to introduce mathematical functions expressing a cost of taking a step, a cost of deviating from a given direction, as well as a cost of deviating from a given speed. In this respect, the referring Board found that this formulation was provided with technical character, based on construing the autonomous entity in the same way as an electron could be considered: a moving entity subjected to spatial constraints/forces.

Once the question of technical character was put aside, the Board concentrated on the solution to a technical problem, in relation to simulation. Given that a simulation implies the devising of a model, i.e. a set of differential equations approximating a physical reality, a simulation cannot as such confer technicality to a claim, since it can be done for scientific or business purposes by using the very same model.

The Enlarged Board of Appeal made it clear that the key general principle for responding to the asked questions is assessing the contribution of a feature to the technical character of the claimed subject-matter in view of the whole scope of the claim. If the very same model underlying the simulation can be used with or without a technical purpose because the claim leaves it unspecified, the claim lacks technical character and therefore a technical problem cannot be solved.

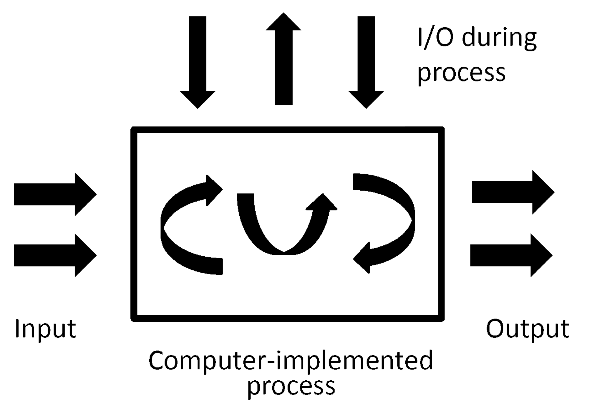

The Enlarged Board of Appeal explicitly represented a computer-implemented method as an input-processing-output flow, also considering that input and output can occur during processing (e.g. by receiving periodic measurement data and/or continuously sending control signals to a technical system):

Technical effects can occur within the computer-implemented process (e.g. by specific adaptations of the computer or of data transfer or storage mechanisms) and at the input and output of this process. For a claim to be patentable, a direct link to a physical reality is not required, as “It is self-evident that the input and output are always nothing other than data, if only the data processing within the computer is considered”. Some form of indirect link to a physical reality, be it external or internal to a computer, must be present but it is impossible to “to exhaustively describe (or represent in graphical form) every type of feature of a computer-implemented invention that may contribute to the invention’s technical character”. This impossibility is beneficial to the concept of technicality, which can be left open to adaptation as technology advances.

Such considerations confirm, in any case, the requirement that there must be a “technical effect going beyond the technical effects within the computer that necessarily occur when a program is run on a computer”. Such further technical effect must be implied by the claim over its whole scope, as above explained, and has to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. The fact that a model underlying a simulation reflects a technical system does not per se assure that there is a further technical effect, for example simulation of non-technical systems such as weather phenomena do not per se imply a further technical effect.

On this basis, the Enlarged Board of Appeal answered the above questions as follows:

- A computer-implemented simulation of a technical system or process that is claimed as such can, for the purpose of assessing inventive step, solve a technical problem by producing a technical effect going beyond the simulation’s implementation on a computer.

- For that assessment it is not a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, in whole or in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process.

- The answers to the first and second questions are no different if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as part of a design process, in particular for verifying a design.

Consequences for Applicants and Practitioners

The clear message of decision G1/19 above illustrated is that computer-implemented simulations are as patentable as any other computer-implemented method. Nothing is to be changed in the patentability assessment criteria utilized so far when computer-implemented simulations are claimed.

In this regard, we find it very valuable that the Enlarged Board of Appeal clarified that technicality of the simulated system or model does not necessarily have an impact on patentability.

A secondary clear message from the Enlarged Board of Appeal is that any assessment of patentability for computer simulated method/simulation must be performed within the framework of the landmark COMVIK decision, therefore the current Guidelines for Examination are fully confirmed and, hence, reinforced.

Such an assessment, says the Enlarged Board of Appeal, must be done on a case-by-case basis, both for the impossibility to exhaustively describe every case of technicality of a claim, and the necessity to leave the technicality concept open for adaptation to future developments in technology.

All in all, applicants and practitioners can fully apply the current Guidelines for Examination to any computer implemented invention, be it in the form of a simulation or not. However, we expect that the clarifications given by the Enlarged Boards of Appeal will be positively reflected in the 2022 version of the Guidelines and therefore on real examinations. It will be fully clear that the Guidelines only summarize well-established patentability criteria with a few examples that cannot substitute assessment of specific case features, which only will be determining the outcome of the examination.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: Joeppoulssen

Image ID: 86141172

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

BP

March 22, 2021 04:58 pmThank you! Very helpful to know. The USPTO does have a simulation example in the subject matter eligibility guidance, though some art units still raise questions.