“[W]hether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from the work.”

On March 26, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York’s decision that Andy Warhol’s Prince Series constituted fair use of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph, holding that “the district court erred in its assessment and application of the fair-use factors and the works in question do not qualify as fair use.” The Court of Appeals further concluded that the Prince Series works were substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph “as a matter of law.”

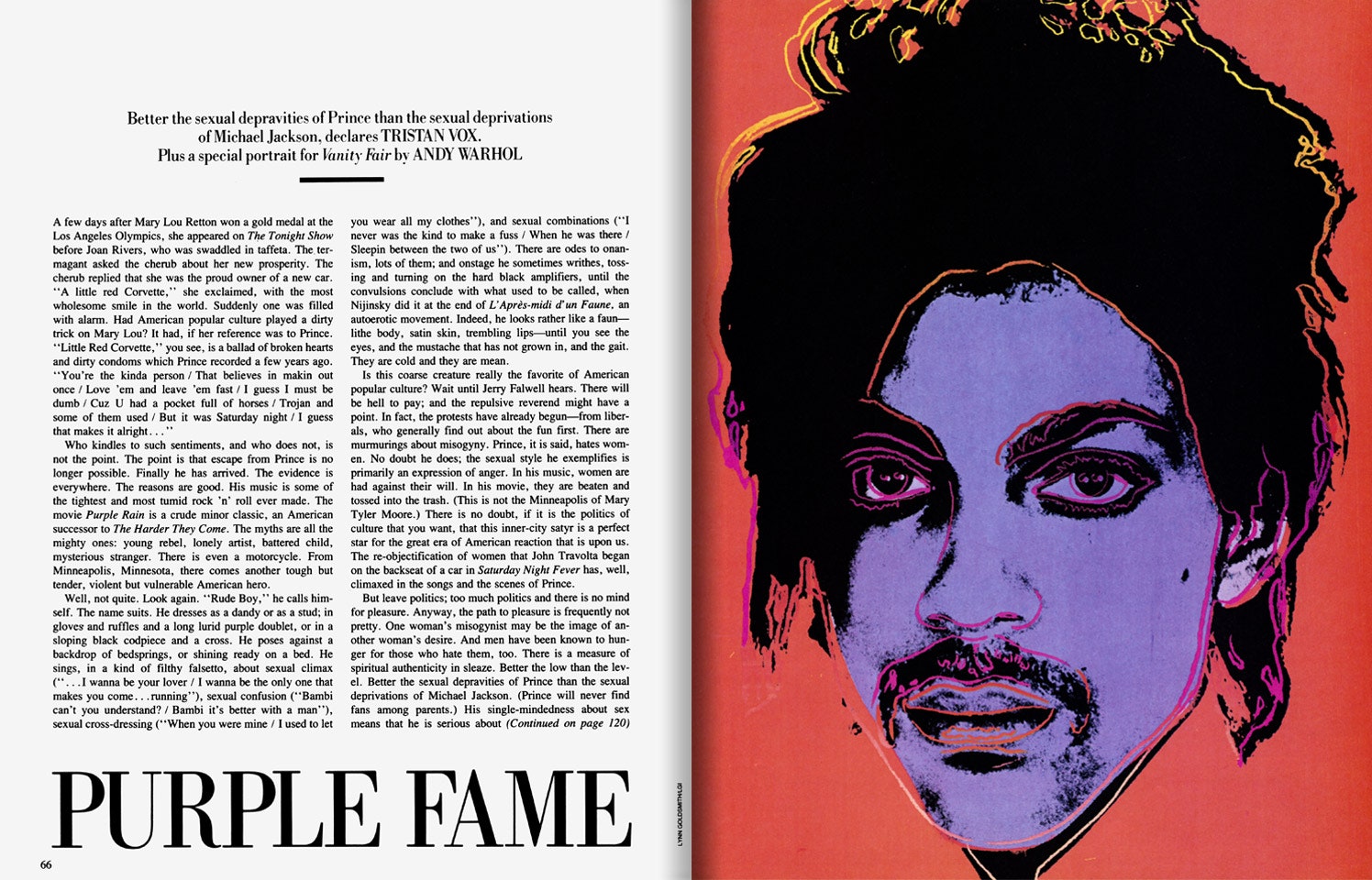

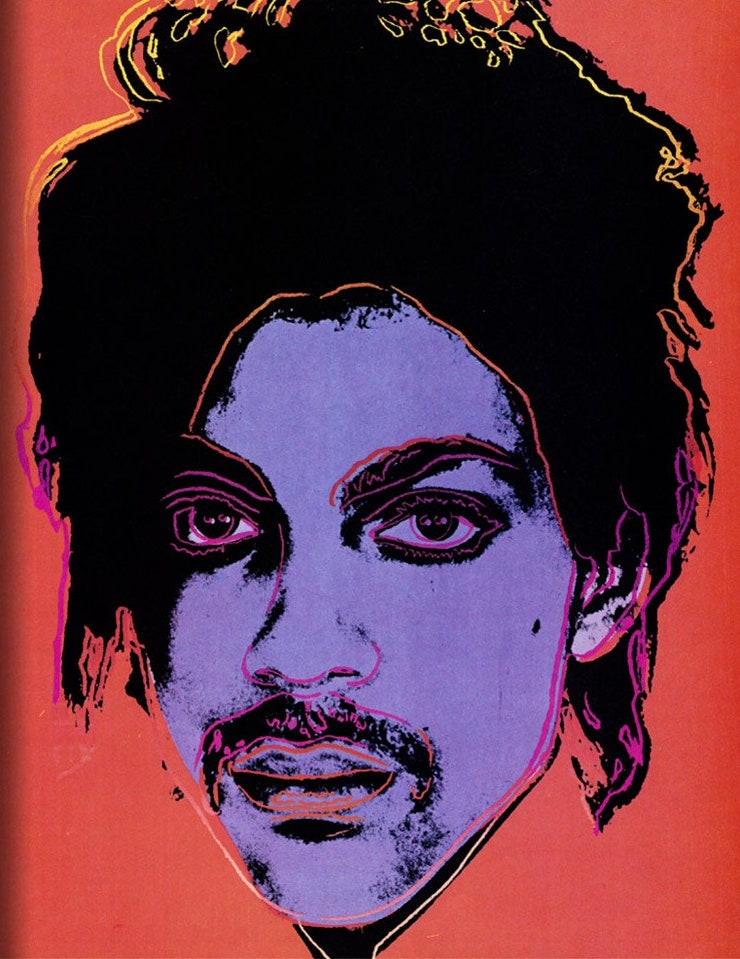

In 1981, Defendant-Appellant Lynn Goldsmith (Goldsmith) took several photographs of the then up-and-coming musical artist Prince Rogers Nelson (Prince). In 1984, Goldsmith’s agency, Defendant-Appellant Lynn Goldsmith, Ltd. (LGL) licensed one of the photographs from the 1981 photoshoot to Vanity Fair magazine “for use as an artist reference.” Unbeknownst to Goldsmith and LGL, the artist who used her photo as inspiration was Andy Warhol, and not only did he use her photo for inspiration for the image Vanity Fair commissioned, but he continued to create an additional 15 works, which are known as the “Prince Series.”

When Goldsmith became aware of the Prince Series in 2016, she notified Plaintiff-Appellee, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF), who is the copyright holder for the Prince Series that she believed the Prince Series violated her copyrighted photo from the 1981 photoshoot. In 2017, upon receipt of this notification, AWF sued Goldsmith and LGL seeking a declaratory judgment that the Prince Series was non-infringing or, alternatively, that the works “made fair use of Goldsmith’s photograph.” In response to AWF’s suit, Goldsmith and LGL countersued for infringement. The lower court granted summary judgment to AWF on its assertion of fair use and dismissed Goldsmith and LGL’s counterclaim with prejudice. On appeal, Goldsmith and LGL argued that the district court “erred in its assessment and application of the four fair-use factors.” Specifically, they argued the district court’s conclusion that the Prince Series is transformative “was grounded in a subjective evaluation of the underlying artistic message of the works rather than an objective assessment of their purpose and character.” The Court of Appeals agreed with Goldsmith and LGL, stating that “the district court’s error in analyzing the first factor was compounded by its analysis of the remaining three factors.” This finding prompted the appellate court to conduct their own four-factor fair use analysis.

Court of Appeals’ Fair Use Analysis

As a starting point, the court noted that under the Copyright Act of 1976, “copyright protection extends to both the original creative work itself and to derivative works.” Quoting Section 101 of 17 U.S.C., the court stated derivative works are defined in the Copyright Act of 1976 as works “based upon one or more preexisting works,” that may be “recast, transformed, or adapted.” However, the court stated, as Justice Story explained in Campbell, few things, if any exist “which in the abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout,” and therefore, “[e]very book in literature, science and art, borrows and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well known and used before.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 575 (1994). Therefore, citing Blanch, the court reasoned that the doctrine of fair use strikes a balance between an artist’s rights to the fruits of their own creative labor, and “the ability of [other] authors, artists, and the rest of us to express them- or ourselves by reference to the works of others.” Blanch v. Koons F.3d 244, 250 (2d Cir. 2006). The Copyright Act provides a non-exclusive list of four factors that courts consider when determining if a work is fair: (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of commercial nature or is for educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

- Purpose and Character of The Use

Citing Campbell, the court noted that the chief concern when evaluating the first factor is the degree to which the use is “transformative,” meaning “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.” 510 U.S. at 579. As part of Section 107 of the Copyright Act, Congress enumerated examples of transformative uses which are “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching …, scholarship, or research.” However, as the Supreme Court emphasized in Campbell, that the fair use analysis is a “context-sensitive inquiry” that does not lend itself to “simple bright-line rules.” 510 U.S. at 577-578.

Quoting the lower court’s decision, the court of appeals decided that the district court improperly identified a bright-line rule when it reasoned that any secondary work is necessarily transformative as a matter of law “[i]f looking at the works side-by-side, the secondary work has a different character, a new expression, and employs new aesthetics with [distinct] creative and communicative results.” Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d at 325-26. While the court of appeals recognized that alterations to the original work is “the sine qua non of transformativeness,” it does not follow “that any secondary work that adds a new aesthetic or new expression to its source material is necessarily transformative.”

In its ruling, the district court held the Prince Series to be transformative because Warhol transformed the Goldsmith Photograph, which depicted Prince as a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to images of an iconic, larger than life figure. The court of appeals corrected the lower court, stating that “whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from the work.” The court reasoned that, if it were otherwise, the law may recognize any alteration as transformative. Therefore, the court must examine how the works may reasonably be perceived without assuming the role of an art critic “seek[ing] to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.” Instead, the judge must determine whether the secondary work’s use of source material is in service of a “‘fundamentally different and new’ artistic purpose and character” in such a way that the secondary work stands apart from the “‘raw material’” used to create it.

The court of appeals recognized Warhol created the Prince Series by removing certain elements such as depth and contrast and adding loud unnatural colors, but that does not make the images transformative as a matter of law. The court therefore determined that the Prince Series was not transformative because it retained the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without adding significantly more. The court underscored the fact that even though the Prince Series may be immediately recognizable as a “Warhol” that does not make the work transformative because “[e]ntertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct the style, the greater leeway the artist would have to pilfer the creative labor of others.”

- The Nature of the Copyrighted Work

Turning to the second factor, the court recognized two issues that must be determined to deduce the nature of the copyrighted work (1) whether the work is creative or factual, and (2) whether the work is published or unpublished. Though the court of appeals agreed with the lower court that the Goldsmith Photograph was both unpublished and creative the two courts come to different conclusions about which party this factor should favor. The lower court believed this factor should not favor either party, recognizing that though the work was creative and unpublished, because the Prince Series was created by obtaining a license and was highly transformative the scope of fair use was larger than a typical unpublished work. The court of appeals corrected the lower court, stating that Goldsmith “made the Goldsmith Photograph available for a single use on limited terms” and that should not change its status as an unpublished work. Therefore, the court of appeals held that this factor favors Goldsmith because the scope of permissible fair use for unpublished works is narrow and the work was not highly transformative.

- The Amount and Substantiality of Use

Quoting Campbell, the court of appeals stated, “the ultimate question under this factor is whether ‘the quantity and value of the materials used are reasonable in relation to the purpose of the copying,’” noting again that there is no bright line rule for what is permissible and what is not. 510 U.S. at 586. AWF’s contention was that this factor favored them, resting their argument on the premise that Goldsmith could not copyright Prince’s face and that “by cropping and flattening the Goldsmith Photograph” Warhol removed or minimized the “expressive qualities” of the Goldsmith Photograph. However, the court of appeals was not convinced, it reasoned that although Goldsmith cannot copyright Prince’s face, she has a broad monopoly on the Goldsmith Photograph and the screen prints that make up the Prince Series are “readily identifiable as deriving from a specific photograph of Prince, the Goldsmith Photograph.” The court cites the fact that the way Prince’s hair falls in the Goldsmith Photograph as evidence that the Prince Series copied the “essence” of the Goldsmith Photograph, noting that other photographs from the same photoshoot do not even portray Prince’s hair in the same way as the Goldsmith Photograph. Contrary to the lower court, which held that this factor favored AWF because Warhol had only taken unprotected elements of the Goldsmith Photograph “in service of a transformative purpose,” the court of appeals ruled this factor favors Goldsmith because the Prince Series was not transformative, nor did it only take unprotected elements.

- The Effect of the Use on the Market for the Original

The key question in assessing the market harm is not whether the secondary work would “damage” the market for the primary work, but rather whether it “usurps” the market for the primary work by offering a competitive substitute. This analysis, the court stated, encompasses the market for both the original work and any potential derivatives. Citing Google, the court reasoned that the first and fourth factors are closely linked, because the more copying that is done for a different purpose than that of the original work “the less likely it is that a copy will serve as a suitable substitute.” Guild v. Google, Inc. 804 F.3d 202, 223.

The lower court found that the Prince Series posed no threat to the licensing market for the Goldsmith Photograph because the market for original Warhol’s and the Goldsmith Photograph do not “meaningfully overlap.” Though the court of appeals agreed that the market for original Warhol’s and the Goldsmith Photograph do not meaningfully overlap, the lower court reached the wrong conclusion because if the conduct AWF engaged in became unrestricted and widespread, it would have a substantial adverse impact on the potential market for the Goldsmith Photograph.

Substantial Similarity

Unsuccessful in convincing the appellate court of fair use, AWF sought in the alternative a ruling that the Prince Series is not substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph, though the court of appeals rejected this as well. AWF urged the court to apply the “more discerning observer” test, however the court stated that test applies to types of works with “thinner” copyright protection, meaning works that contain a larger share of non-copyrightable elements. The court of appeals, citing Knitwaves, reasoned that the proper test will show “two works are substantially similar when ‘an average lay observer would recognize the alleged copy as having been appropriated from the copyrighted work.’” Knitwaves, Inc. v. Lollytogs, Ltd., 71 F.3d 996, 1003 (2d Cir. 1995). The court therefore concluded that the photographs were substantially similar because “any reasonable viewer” would have no difficulty identifying the Goldsmith Photograph “as the source material for Warhol’s Prince Series.” Accordingly, the court of appeals concluded that all four factors favor Goldsmith and LGL and therefore the lower court’s ruling was reversed.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.