“The large number and diverse ownership of 5G RAN SEPs should encourage a frenzy of monetization activity. Questions of primary and secondary infringement will, however, require careful consideration.”

Changes in the 5G radio access network (RAN) are likely to increase interest in monetizing patents essential to RAN equipment and operations (RAN SEPs). One of these changes is the significant increase in the volumes of equipment like radio units (RUs) expected over the next decade. For example, China alone plans to deploy 6 million 5G cells by 2027, at an average cell spend of $28,500.

Changes in the 5G radio access network (RAN) are likely to increase interest in monetizing patents essential to RAN equipment and operations (RAN SEPs). One of these changes is the significant increase in the volumes of equipment like radio units (RUs) expected over the next decade. For example, China alone plans to deploy 6 million 5G cells by 2027, at an average cell spend of $28,500.

Other changes likely to spur 5G RAN licensing are the increase of new entrants to the RAN equipment market and the use of open source software and off-the-shelf hardware in new RAN deployments. These latter changes are driven by the new Open RAN model promoted by operators seeking to break vendor lock in and foster equipment democratization and price competition. These changes naturally could pose a threat to the traditional RAN equipment businesses like Ericsson, Huawei, Nokia, Samsung, and ZTE, who number among the top eight technical contributors to 5G RAN standardization and hold a significant portion of the self-declared 5G RAN SEPs.

RAN SEP Landscape

The RAN patent licensing market will not, however, be without challenges. One of the challenges is the sheer number of patents and applications claimed to be relevant to 5G RAN and the diversity of their ownership.

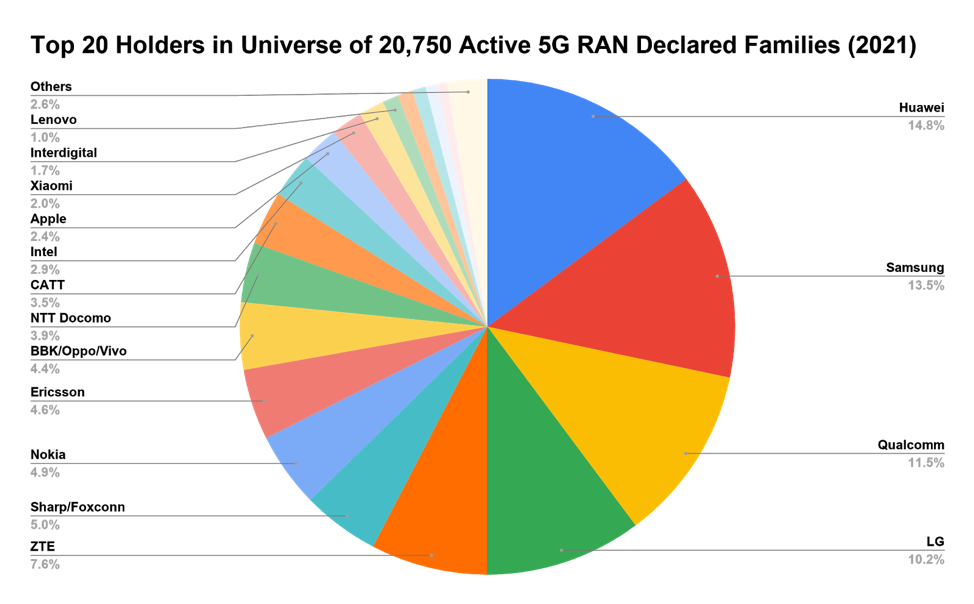

As of January 2021, nearly 33,000 active patent families have been self-declared to 5G. Of those families, over 63% or 20,750 families have been self-declared specifically to 5G RAN infrastructure. These families comprise nearly 70,000 active patents and applications. The pie chart below developed from Unified Patents’ objective patent landscaping tool (OPAL) shows the top 20 ownership of those families.

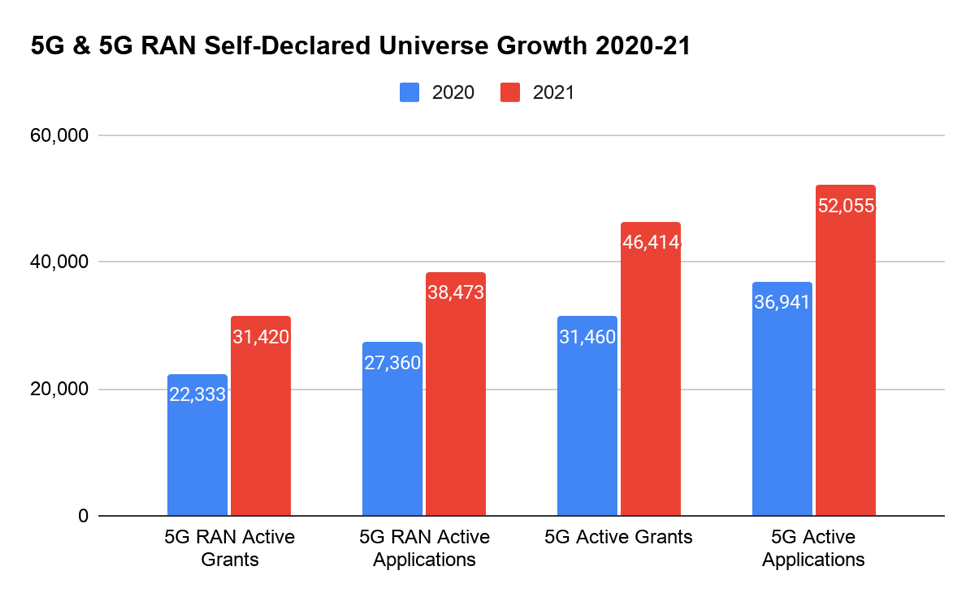

The number of active granted patents currently self-declared to 5G RAN is about 31,400 but that leaves over 55% of the 70,000 self-declared publications still pending. The number of self-declared publications is growing fast as the 5G RAN grows in complexity. In comparison, 14K patents and applications had been self-declared to LTE RAN as of February 2012 – about 2.5 years after the 2009 freeze of the initial LTE RAN standard which corresponds to the same amount of time that has passed between the 2018 freeze of the initial 5G standard and today. Currently, over 91,000 patents and applications (23,000 families) have been self-declared to LTE. If the number of 5G self-declared patents and applications grows as the number of LTE grants and applications grew over the last nine years at an annual rate of over 9%, the number of 5G self-declared grants and applications could reach an astounding 200,000 by 2030. The increase in self-declared publications just from 2020 to date doesn’t bode well for those hoping for a more manageable 5G patent landscape.

Of course, the numbers stated above represent only the patents and applications self-declared by entities participating in 5G standardization. These numbers do not capture the tens of thousands of potentially relevant patents and applications that have not yet been self-declared by 5G standardization participants or that are owned by entities that do not participate in 5G standardization work. The OPAL tool identified over 15,000 active, undeclared grants and applications that have a very high degree of semantic similarity (a score of 80 on a scale of 0-100 with 100 being the highest) with patents and applications already self-declared to be essential to 5G.

Of course, the numbers stated above represent only the patents and applications self-declared by entities participating in 5G standardization. These numbers do not capture the tens of thousands of potentially relevant patents and applications that have not yet been self-declared by 5G standardization participants or that are owned by entities that do not participate in 5G standardization work. The OPAL tool identified over 15,000 active, undeclared grants and applications that have a very high degree of semantic similarity (a score of 80 on a scale of 0-100 with 100 being the highest) with patents and applications already self-declared to be essential to 5G.

Further, these numbers do not indicate whether these self-declared patents and applications are actually essential to the referenced standards. The essentiality rates associated with past 3GPP standards such as 2G, 3G, and LTE are as a rule less than 50% and some even as low as 13%. There is no reason to believe that the self-declared essentiality rate for 5G will be any better.

The traditional RAN vendors Huawei, ZTE, Nokia, Ericsson, and Samsung combined have self-declared about 9,400 families to be essential to 5G RAN. This represents about 45% of the universe of patent families so declared. Any defensive licensing strategy should take into account potential assertions from these entities as they are the most threatened by the commoditization of the RAN. The FRAND obligations undertaken by these entities should, however, elide any hold-up scenarios and be conducive to the growth of a competitive RAN market.

Liability for Infringement

The disaggregation of the 5G RAN into centralized baseband processing units (CU), distributed baseband processing units (DU), and radio units (RU), discussed in an earlier article here, leads to some thorny issues from an SEP licensing perspective. In the new 5G RAN architecture, the processing of the 5G baseband and hence the infringement of RAN SEPs will occur across a number of network components supplied by a number of different vendors. The main questions don’t get any easier: where does the infringement occur and who is responsible for the infringement?

Primary Liability for Infringement

Patent infringement in the United States requires that the use, sale, offer to sell, or import of a patented invention is directly infringed. Identifying the entity directly and primarily responsible for such activities involving equipment that comprises all the elements of a patent claim is a relatively straightforward task. But the task of imputing liability becomes daunting and even costly from an evidentiary perspective when the elements of a patent claim are performed by a combination of several devices in a distributed network system or as a method the steps of which are practiced by several entities.

- In a commercial combination of products, a vendor of an RU that does not include the means to perform some of the elements of a patent claim may not be primarily liable for direct infringement. In such a case, a licensor would have to assert against the operator or system integrator that combines the RU with a DU / CU to perform all the elements of the patent claim.

- With respect to a patented method, a distributed antenna system (DAS) owner using an RU or an antenna array may not be primarily liable for direct infringement where one of the elements of the method claim are performed by a mobile network operator using a CU. A licensor in such a case would have to identify the controlling entity and show divided infringement.

Either of these scenarios will likely be a gating issue for traditional RAN vendors that seek to assert their SEPs against their operator-customers. Discussions where a vendor asks its operator-customer for permission to sue them as a primary infringer usually don’t go over well— if they’re even allowed to take place.

Divided Infringement

In limited cases, 5G RAN SEP holders could look beyond the traditional operator for primary infringement liability if the infringement benefits and is orchestrated by another entity. Such cases could, for instance, arise when traditional operators perform a supporting role for private networks operated by DAS owners.

Prior to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit’s 2015 en banc decision in Akamai v. Limelight, an entity could be found to be a direct infringer and thus primarily liable for infringing a patented method if:

- the entity performs itself all the steps of the patent method,

- the entity acts through an agent, or

- the entity contracts with another to perform one or more steps of the patented method.

The court in Akamai v. Limelight also found that primary liability for another entity’s actions could be attributed to an entity if that entity conditions the other entity’s receipt of a benefit upon the other entity’s performance of some of the steps of a patented method and establishes the manner or timing of that performance.

It would seem plausible that a DAS operator could be held primarily liable for the acts of a mobile network operator that initiated or completed the steps required in a patented method if the DAS operator contracts with the mobile network operator to perform the steps. As an example, a DAS operator could contract with a mobile network operator to route and terminate traffic originating from its RUs covering, for instance, a sports stadium or a business campus. A similar finding of primary liability for a DAS operator could arise under the Federal Circuit’s 2017 decision in Travel Sentry v. Tropp where a DAS operator interconnects with a mobile network operator under even a non-binding MoU and conditions the routing and termination of traffic generated in the DAS upon compliant performance of certain steps required in a patented signal processing method.

The question of who supports whom in the 5G RAN should be fact based. The controlling role of operators in heterogeneous networks could come under scrutiny, particularly where the networks operate at unlicensed frequencies.

Secondary Liability

Once direct infringement is provable, licensors can direct their assertion at any entity that directly infringes the patented invention or at any entity that either induces the direct infringement or can be found to have contributed to the infringement.

In the United States, inducement and contributory infringement require under 35 U.S.C. § 271(b) and § 271(c) a finding that the inducing or contributing entity had prior knowledge of the patent or at least there is no showing of willful blindness. The U.S. Supreme Court in its 2011 decision in Global-Tech Appliances vs. SEB stated that a finding of wilful blindness can overcome a lack of actual knowledge if the defendant can be found to have “…subjectively believe[d] that there is a high probability” of a fact and then taken “…deliberate actions to avoid learning of that fact.” The U.S. Supreme Court went further in its 2015 decision in Commil USA vs. Cisco to require that inducement requires also that the defendant had knowledge of not just the patent but also that its inducement would cause infringement.

The application of the willful blindness standard has been scrutinized recently in the courts with respect to motions to dismiss with differing results. In Motiva Patents v. Sony, HTC, the Eastern District of Texas found in 2019 that the existence of a patent non-review policy was sufficient to state a claim of willful blindness. Interestingly, the same court came to the opposite conclusion in 2016 in Nonend Inventions v. Apple in finding that a patent non-review policy does not per-se constitute willful blindness for the purposes of enhanced damages. The Delaware District also concluded in 2019 in VLSI Tech v. Intel that a patent non-review policy does not, without more, constitute willful blindness. In none of these cases was there a showing that the defendant subjectively believed that there was a high probability of the existence of a patent. The decision in the Motiva Case vs. Sony case may just be an aberration but it is likely that plaintiffs in the Eastern District of Texas will refer to it until it is overturned at the 5th Circuit.

The case law and 35 U.S.C. § 271(b) and § 271(c) also require for a finding of inducement or contributory infringement that the intent to cause infringement be shown. While intent is difficult to show, strict compliance with standards and operator requirements may make the task easier particularly if the infringement is sufficiently detailed in the standard or operator requirements and the vendor warrants compliance.

Contributory infringement can be rebutted if, for instance, the product giving rise to the claim of contributory infringement can be shown to have non-infringing uses. Since the aim of the open RAN alliances, O-RAN and OpenRAN, is to design and build the RAN around general purpose hardware, it is arguable that RUs so designed and built could frustrate a claim of contributory infringement at least with respect to the hardware. In contrast, software running on RUs to implement BBU functionality may not have a non-infringing use and such rebuttal may not be effective.

A Frenzy of Activity Ahead

The rapidly changing 5G RAN and the growth forecasts for the equipment market promises to attract 5G RAN SEP monetization. The large number and diverse ownership of 5G RAN SEPs should encourage a frenzy of monetization activity. Questions of primary and secondary infringement will, however, require careful consideration. Traditional 5G RAN vendors may find their efforts to monetize their 5G RAN SEPs hampered by their business goals to sell RAN equipment to their operator-customers. Of course, as is evident from Huawei’s infringement lawsuit against Verizon, when product business goals are frustrated by government security and trade policies, such will likely yield to the potential profitability offered by patent monetization and the threat the new changes to the traditional RAN equipment market portends.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: jamesteohart

Image ID: 182552442

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.