“Patents offer a historical record, not just of major technology turning points, but also of the kinds of incremental innovations that underpin national economic growth.”

Patent Office built after the 1836 fire. Source: Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2012648853

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) issued its 11 millionth patent today, May 11, 2021. America’s first (unnumbered) patent was issued in July of 1790, and patents were numbered consecutively starting in 1836. From there, the pace of patenting accelerated, with 100,000 patents issued by early 1870 and the 1 millionth issued in 1911. Since 2010, the USPTO has issued an average of over 300,000 new patents annually, as inventors and firms around the world have look to the United States as the premier global patent location.

This article provides a brief history of patents issued with milestone numbers. There are numerous invention histories that identify patents with the greatest societal or economic impact. That is not my aspiration here. Whether or not patent office officials are stacking the deck to make milestone patents especially important (history suggests they have not done so), this chronology instead offers a broader survey of technology change over the past 231 years and demonstrates the value of incremental change that is a core characteristic of the majority of innovations we interact with in our daily lives.

Patent X1

The first patent issued in the newly established United States went to the inventor and Philadelphia-based businessman Samuel Hopkins, who had developed an improved method of making potash and pearl ash. Produced by burning newly cleared indigenous hardwood forests across New England and the mid-Atlantic, potash was used as a fertilizer, as a detergent to clean fibers in textile manufacturing, and to make soap. Pearl ash was a more refined material used in glassmaking, to make saltpeter for gunpowder, and as a leavening agent for baking (baking soda and baking powder were not invented until the 1840s). Potash and pearl ash both had a reliable cash value, which in many cases was used to pay for land clearing and the initial start for farmers in new rural communities.

Hopkins’ patent itself enumerated a four-step process for his improved process that included a second burning of ashes, dissolving the ash in hot water, and then concentrating the potash by boiling the mixture in a specially designed brick furnace. He also initiated the nation’s first patent licensing program by visiting frontier areas, speaking about his invention, publishing a pamphlet describing his breakthrough, and establishing legal agents in cities across the northeast who could sign licenses on his behalf. Historical records are spotty, but Hopkins does not appear to have had great success at monetizing his invention; by 1800 he had moved in with his daughter and son-in-law in New Jersey. He did continue to invent and secured patents on methods for producing “flour of mustard” in 1813 and 1817.

Patent 1

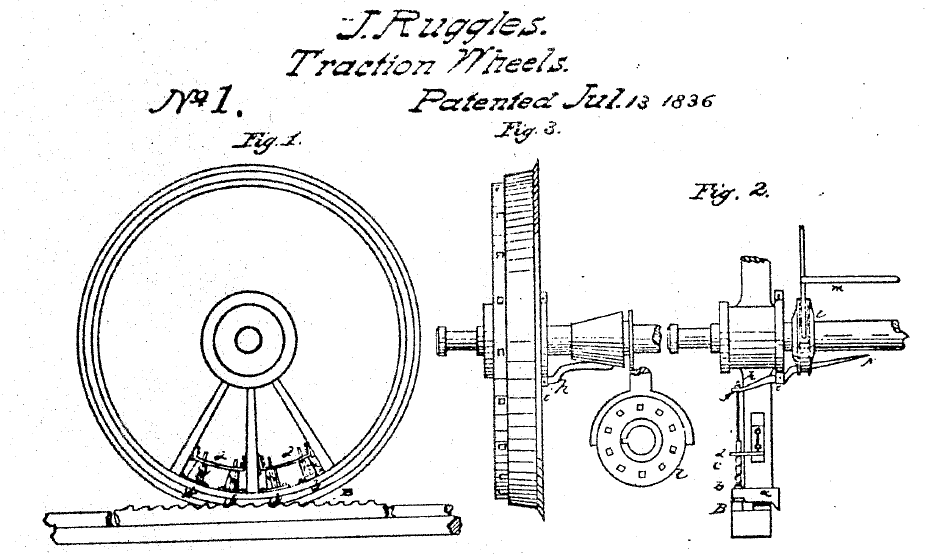

Patent #1: John Ruggles’ Train Cogwheel. Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office.

In what proved a transformative year for the U.S. patent system, a new Patent Act was passed on July 4, 1836. Championed by the Maine Senator John Ruggles (chair of the Committee on Patents and the Patent Office), the 1836 Act specified how inventions should be described, called for drawings and references, and in a boon to other inventors throughout the 19th century (and later to the Smithsonian and other museums), asked inventors to submit of physical models of their inventions. It also set standards for the “examination” of submissions and gave applicants the opportunity to reply to questions posed by examiners. Later the same year, on December 15, a fire destroyed the Patent Office and nearly all of its records. Subsequent efforts to document lost inventions identified only some 2,800 records out of an estimated 10,000 patents from the 1790-1836 period.

The first patent issued under the 1836 Act – and the start of sequential numbering – went to none other than John Ruggles for a “locomotive steam-engine for rail and other roads.” Coming as rail construction was just starting to expand in the United States, Ruggles’ cogwheel invention increased “tractive power” to the locomotive and reduced backsliding on hills or on ice or snow-covered rails. The system featured notched plates along the tracks and incorporated a clever way to engage a cogwheel when traction was needed and to withdraw the cogs for descents. While Ruggles was a successful lawyer and is credited to this day for his work on the 1836 Patent Act, his invention was not widely taken up. Mountain cog rails were built starting in the 1860s using rack and pinion systems but were developed after Ruggles’ patent had expired. Ruggles himself returned to Thomaston, Maine in 1841, where he had a law practice and was known as an inventor and orator, though no records have surfaced of his later inventions.

Patent 100,000

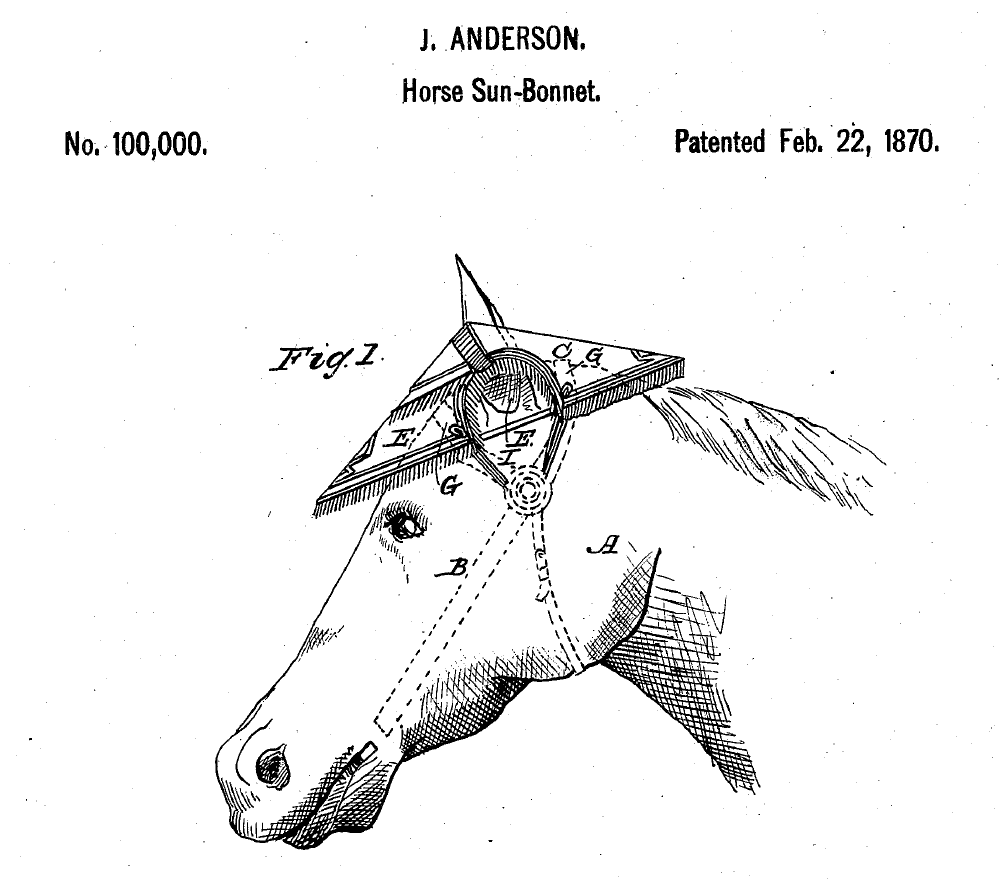

Patent #100,000: John Anderson’s Horse Sun-Bonnet. Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office.

In 1870, the inventor John Anderson received patent 100,000 for what is likely the most idiosyncratic of the milestone patents, namely for a “horse sun-bonnet.” Using elastic attachments and bands to secure the bonnet to a horse’s head, Anderson’s invention was an improvement on a prior patent he had received in 1869. While obscure, Anderson went on to secure a design patent (number 5,210) in 1871 for the horse sun-bonnet and a third patent in 1873 for an improved sun-bonnet that was lighter and allowed for greater air circulation. Sun-bonnets were used during the Victorian era to protect horses pulling carriages used by wealthy Americans as well as those pulling or custard or other food carts who stood in the sun for long stretches.

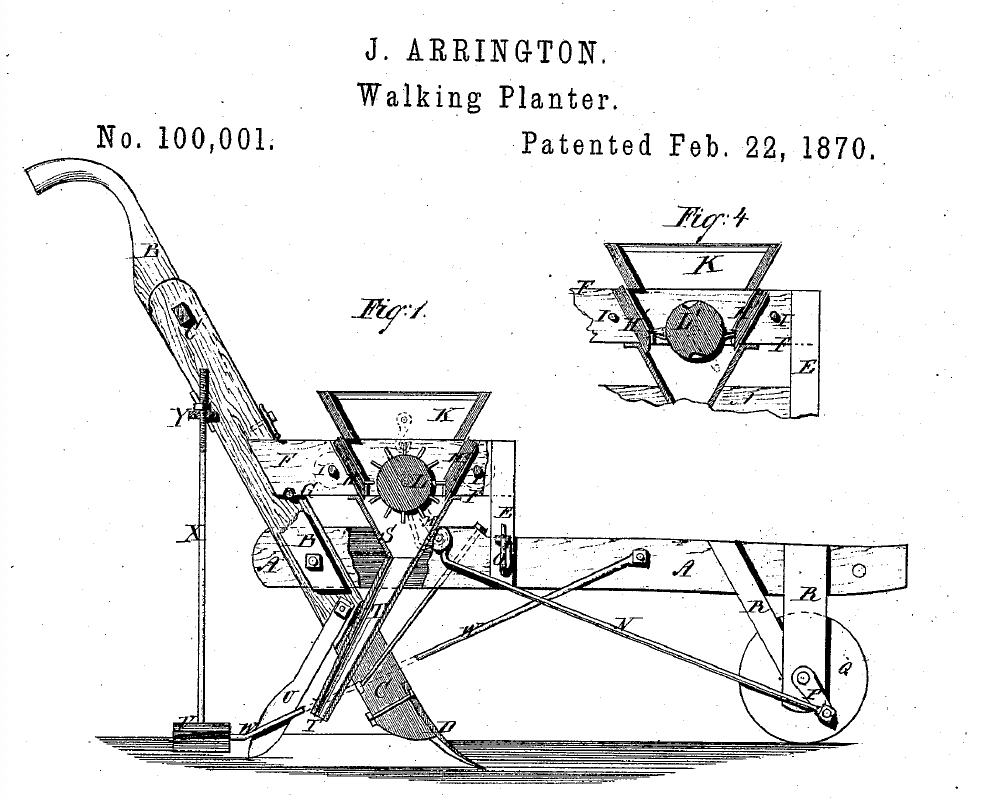

Patent #100,001: Joseph Arrington’s Walking Planter. Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office.

The next patent, number 100,001, aligned to the shifts in American farm technology after the Civil War with an improved “seed-planter and fertilizer-distributer.” Invented by Joseph Arrington of Livingston, Alabama, the “Walking Planter,” as he termed it, was designed to dig a trench, plant cotton seeds, distributed controlled amounts of fertilizer, and fold the soil back in a single process. Arrington’s machine would have been of great use to farmers in the South, where soils were soft enough to plough by hand and horses or mules pulling larger ploughs were too expensive for many. Across the region, the post-Civil War period was characterized by sharecropping and tenancy arrangements in which both poor white and formerly enslaved Black laborers worked fields in exchange for a share of the crops. Any inexpensive improvement to ploughing and planting was likely to gain some uptake. However, as with the majority of 19th century inventors, few if any historical records point to what Arrington did with the patent once it issued, and he did not earn any further patents.

Patent 1 Million

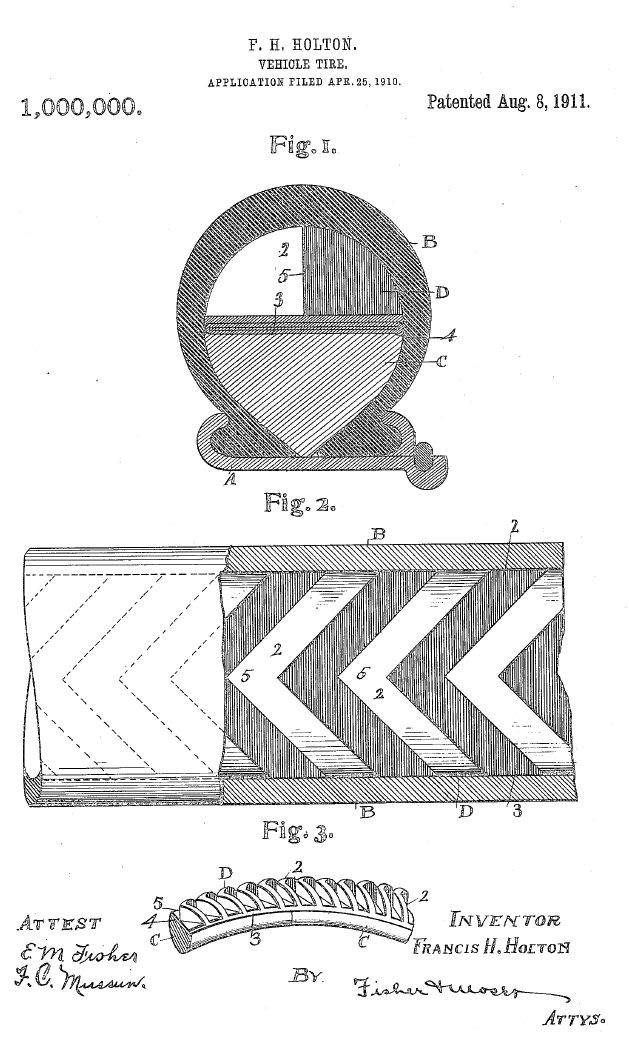

Issued in 1911, patent one million went to Francis Holton from Akron, Ohio, for an improved pneumatic vehicle tire that was more durable, less likely to puncture, and less expensive to manufacture than previous tires. Notably, Holton sought a balance between having a thick solid tire that did not puncture and an air-inflated tire that weighed less and gave a smoother ride. A hot area of invention, over 4,000 tire patents were issued between the 1880s and 1910s. The new Holton tire had a “cellular or honeycombed” structure that yielded under pressure, but then bounced back reliably. In effect, it had an open structure, rather than being an enclosed inflated tire.

Issued in 1911, patent one million went to Francis Holton from Akron, Ohio, for an improved pneumatic vehicle tire that was more durable, less likely to puncture, and less expensive to manufacture than previous tires. Notably, Holton sought a balance between having a thick solid tire that did not puncture and an air-inflated tire that weighed less and gave a smoother ride. A hot area of invention, over 4,000 tire patents were issued between the 1880s and 1910s. The new Holton tire had a “cellular or honeycombed” structure that yielded under pressure, but then bounced back reliably. In effect, it had an open structure, rather than being an enclosed inflated tire.

As a major milestone patent number, Holton’s invention was covered by the New York Times (August 20, 1911, p.M12), which considered it “a peculiarly up-to-the-minute contraption … being indeed for nothing less than a non-puncturable automobile tire, one of the crying necessities of this modern world.” Amusingly, Holton listed “bicycles, motor cycles and the like” in his patent, but made no mention of cars. As with many of the inventors before him, there is little about Holton in the public record, and he did not have any other patents issued after his improved tire.

Patent 5 Million

University of Florida professor Lonnie O. Ingram and researchers Tyrrell Conway and Flavio Alterthum were issued patent number 5 million in 1991 for inventing a modified E. coli bacterium that produced ethanol. Granting intellectual property protections for life forms has a history that includes the 1930 Plant Patent Act, which allowed protection of new asexually reproducing plant varieties, and the 1980 Diamond v Chakrabarty Supreme Court Case, which extended patent protection to human-engineered microorganisms.

Specific claims in the Ingram, Conway, and Alterthum patent covered the E. coli transformation while broader claims covered the production of ethanol from a variety of biomass materials ranging from grass clippings to wheat stalks to cardboard and newsprint. Ingram would go on to earn 35 patents, authored over 250 publications, and worked with a variety of applied biorefinery projects to advance renewable fuel production technologies. Conway became a professor at Oklahoma State University and Alterthum would author Brazil’s leading microbiology textbook while on the faculty of the University of São Paulo.

Patent 11 Million

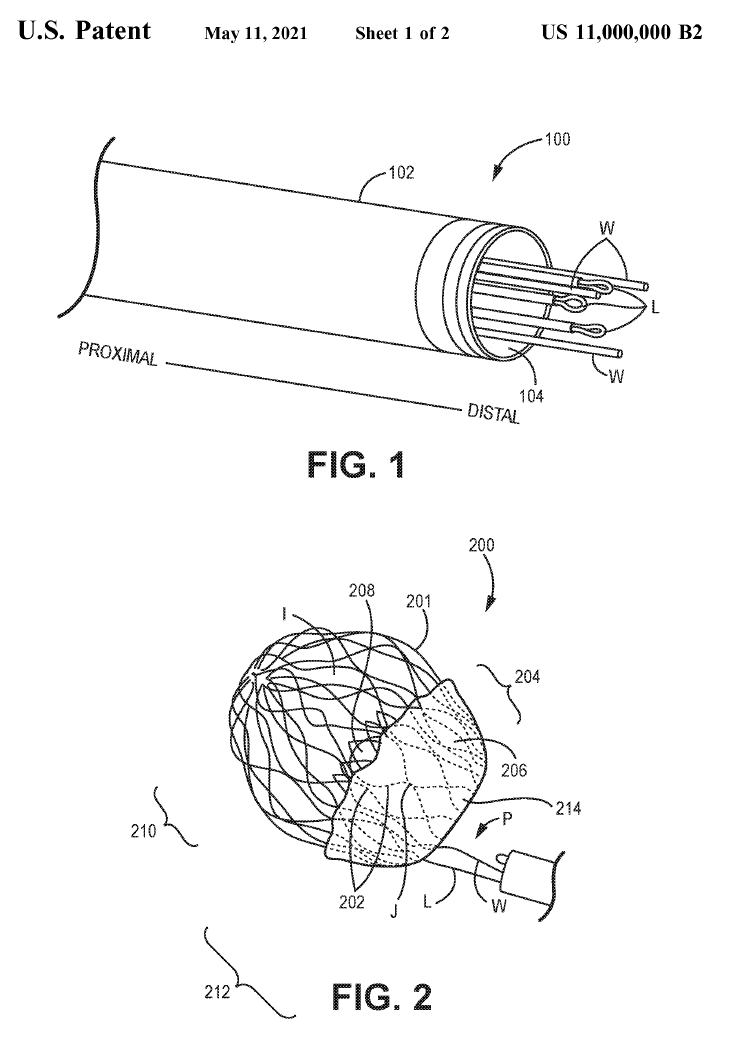

The 11 millionth patent was issued today to co-inventors Jason Diedering and Saravana Kumar at 4C Medical Technologies in Maple Grove, Minnesota, for a medical device that positions (or repositions) an expandable prosthetic valve in a patient’s heart. Coronary stents have been implanted through minimally invasive surgery since the mid-1980s, and transcatheter heart valve surgery (in which a thin wire or tube is threaded through an artery to the heart and a new valve is placed) slowly gained acceptance in the early 2000s. The new device and approach is especially targeted to situations in which blood is flowing backward through the mitral heart valve. It enables physicians to implant an expandable prosthetic valve while using multiple looped and flat-ended wires to position or reposition the valve with greater precision than was possible in the past. Founded in 2015, 4C Medical Technologies is building on a legacy of new cardiac technologies and medical device startups in central Minnesota, beginning with the cardiac pacemaker that was invented at Medtronic when it was a small startup in the mid-1950s.

The 11 millionth patent was issued today to co-inventors Jason Diedering and Saravana Kumar at 4C Medical Technologies in Maple Grove, Minnesota, for a medical device that positions (or repositions) an expandable prosthetic valve in a patient’s heart. Coronary stents have been implanted through minimally invasive surgery since the mid-1980s, and transcatheter heart valve surgery (in which a thin wire or tube is threaded through an artery to the heart and a new valve is placed) slowly gained acceptance in the early 2000s. The new device and approach is especially targeted to situations in which blood is flowing backward through the mitral heart valve. It enables physicians to implant an expandable prosthetic valve while using multiple looped and flat-ended wires to position or reposition the valve with greater precision than was possible in the past. Founded in 2015, 4C Medical Technologies is building on a legacy of new cardiac technologies and medical device startups in central Minnesota, beginning with the cardiac pacemaker that was invented at Medtronic when it was a small startup in the mid-1950s.

Commenting on issuing the milestone patent, Acting USPTO Director Drew Hirshfeld said that the subject matter of the 11 millionth patent offers “a reminder of just how lucky we are at USPTO to be working with innovators so focused on advancing society.”

Patents Have a Complex and Elusive History

Patents offer a historical record, not just of major technology turning points, but also of the kinds of incremental innovations that underpin economic growth. In the United States, where enthusiasm around new technology and inventors has long been a key feature of the national identity, patents also are at the forefront of debates over how to incentivize invention and how to diversify who participates in science, engineering, and entrepreneurship. That history is complicated and fraught, especially when it comes to women and Black inventors, who often find it very challenging or even impossible to secure the support needed to go from the creative act of inventing to the more commercial experience of patenting and licensing or selling their products or services. Considerable work lies ahead for historians and others who get interested in this topic; even for some of the most-cited inventions of the past, we know next to nothing about the inventors themselves or what they did with their patents once issued.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

4 comments so far.

PTO-indentured

May 12, 2021 11:03 amAnd now: a most-recent decade of history yielding a million+ U.S. patents, relegated — knowingly (and thus intentionally) –defenseless.

The real ‘news’ in U.S. patents is not the number that ‘grant’ it is a butchery of such a vast number of them that are so dependably killed ‘post-grant’. Everyone knows this. No one (capable of doing something) is doing anything to stop it.

Consolation prize: Well, at least we get to know it’s because “powerful forces” want U.S. inventors / innovators kept utterly powerless.

AND! We get to call the reaching of this 11th million U.S. patent threshold — following a decade of intentional debasement of U.S. patent value — ‘history!’

PTO-indentured

May 12, 2021 11:01 amJohn @2

During the recent (excellent) four-day webinar series Winning at the PTAB one of the esteemed panelist stated words akin to: These days it would almost be considered malpractice if an IP firm did not use the very tools unleashed by congress, AIA and the courts… those so effectively, reliably and predictably proven to invalidate U.S. patents.

John

May 12, 2021 07:08 amAre there law firms that specialize in invalidating patents?

IPdude

May 11, 2021 08:42 pmOver 90% are invalid, thanks to current law, so really more like the millionth patent issued. Bravo…smh.