“The notion of patent-eligible subject matter applies only to utility patents. As a result, the enforcement of design patents avoids this potential area of dispute and attendant risk of invalidation, resulting in increased certainty for the patent holder.”

Design patents provide powerful protections both on their own and as a complement to their more well-known cousin, utility patents. The highly publicized Apple v. Samsung lawsuits of the previous decade featured both design and utility patents, and revitalized public awareness of design patents in general. In fact, it was infringement of the design patents that resulted in the large damages awards in those litigations, with three design patents resulting in an award of $533.3 million and two utility patents only $5.3 million.

Beyond the likelihood of greater money damages, as compared to their utility patent counterparts design patents are also less expensive to obtain and hold, offer simpler determinations of infringement and validity, and are less susceptible to being invalidated (whether, e.g., for non-patent eligible subject matter or via a post-grant procedure). As such, design patents are more likely to survive, potentially resulting in substantial damages for the patent holder.

This article explores some key differences between design and utility patents, using a design patent recently litigated by Blackbird Technologies (Blackbird) as an example.

Design Patent Scope

Section 35 of the United States Code, known as the Patent Act, states that a design patent protects “any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture,” whereas a utility patent protects “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” Put differently, design patents protect the decorative aspects of a product and utility patents protect the functional features. For example, a utility patent on a smartphone could cover technology such as unlocking, video calling, and texting, whereas a design patent could cover the shape of the phone, such as the rectangular body with rounded edges of an iPhone. It is valuable to obtain both utility and design patents on the same product, as doing so makes it more difficult for a competitor to develop a similar product that does not infringe at least one type of patent.

The scope of any patent is defined by its claims. While utility patents typically have multiple claims of varying scope, design patents have a single claim typically in the form of:

An ornamental design for [the particular article of manufacture] as shown and described.

One of the design patents at issue in the Apple v. Samsung litigations, U.S. Patent No. D618,677, claims “The ornamental design of an electronic device, as shown and described.”

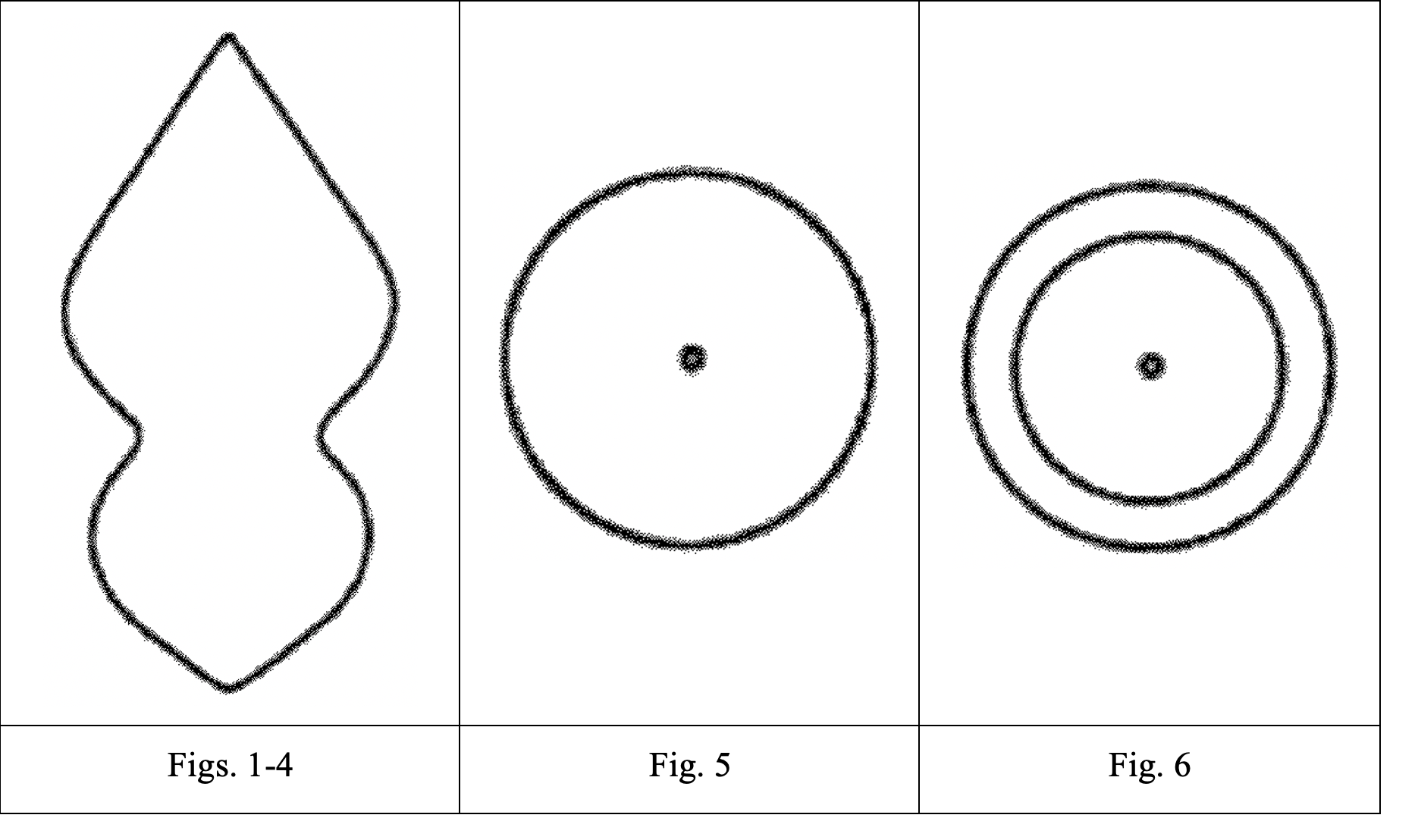

Blackbird recently concluded a series of litigations involving U.S. Patent No. D666,358 (the “D’358 Patent”), which relates to a design for a makeup applicator sponge and claims “[a]n ornamental design for a face sponge, as shown and described.” The face sponge patent includes the following figures:

These figures depict views from all sides of the face sponge, including the top and bottom. The figures convey the scope of the claimed ornamental design of the D’358 Patent.

Simple Claim Construction

Claim construction, where a court interprets disputed terms of a patent’s claim language, can make or break a case. Indeed, when a defendant obtains a construction that is sufficiently narrow, the accused device will not infringe that claim. Similarly, when a defendant obtains a construction broad enough to encompass the prior art, the patent is invalid. Constructions of even a single claim term can be determinative of the entire litigation.

For utility patents, claim construction typically involves a thorough analysis of a patent’s disclosure and file history. It also often involves opinions of competing experts, analysis of technical publications, and other considerations for the court to take into account. While courts frequently provide detailed textual constructions for utility patent claims, that process is discouraged in the case of design patents. As such, the risks associated with claim construction is significantly lower when asserting a design patent.

Design patents contain a single claim, which the courts have found best construed simply by reference to the patent’s drawings. In Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, a seminal case concerning interpreting design patent claims, the Federal Circuit explicitly stated that it does not “require[] that the trial court attempt to provide a detailed verbal description of the claimed design, as is typically done in the case of utility patents… if it does not regard verbal elaboration as necessary or helpful.” Indeed, “a design is better represented by an illustration than it could be by any description and a description would probably not be intelligible without the illustration.”

The Federal Circuit has examined this issue multiple times, reiterating that “misplaced reliance on a detailed verbal description of the claimed design risks undue emphasis on particular features of the design rather than examination of the design as a whole” and that “[d]epictions of the claimed design in words can easily distract from the proper infringement analysis of the ornamental patterns and drawings.”

In the Blackbird face sponge litigations, Blackbird proposed a construction of the claim that simply referenced the figures:

An ornamental design for a face sponge, as shown and described in Figs. 1-6.

Ease of Proving Infringement

Infringement of a utility patent claim is found by establishing that the accused device includes each and every limitation of the claim(s) at issue. As utility patents typically contain numerous claims, each with multiple limitations, this process can be highly technical and detailed, introducing complexity, delay, and expense. Because a utility patent defendant may avoid infringement if even one claim element is missing from its accused product, this provides many possible avenues for a defendant to avoid liability.

By contrast, the test for infringement of a design patent articulated in Egyptian Goddess is the “ordinary observer test” and examines whether the accused article “embod[ies] the patented design or any colorable imitation thereof.” More particularly, infringement is found when the “accused design [is] so similar to the claimed design that a purchaser familiar with the prior art would be deceived by the similarity between the claimed and accused designs, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other.” Simply put, infringement occurs when someone buying the accused product who is aware of the prior art believes it to be, or be very similar to, the patented design.

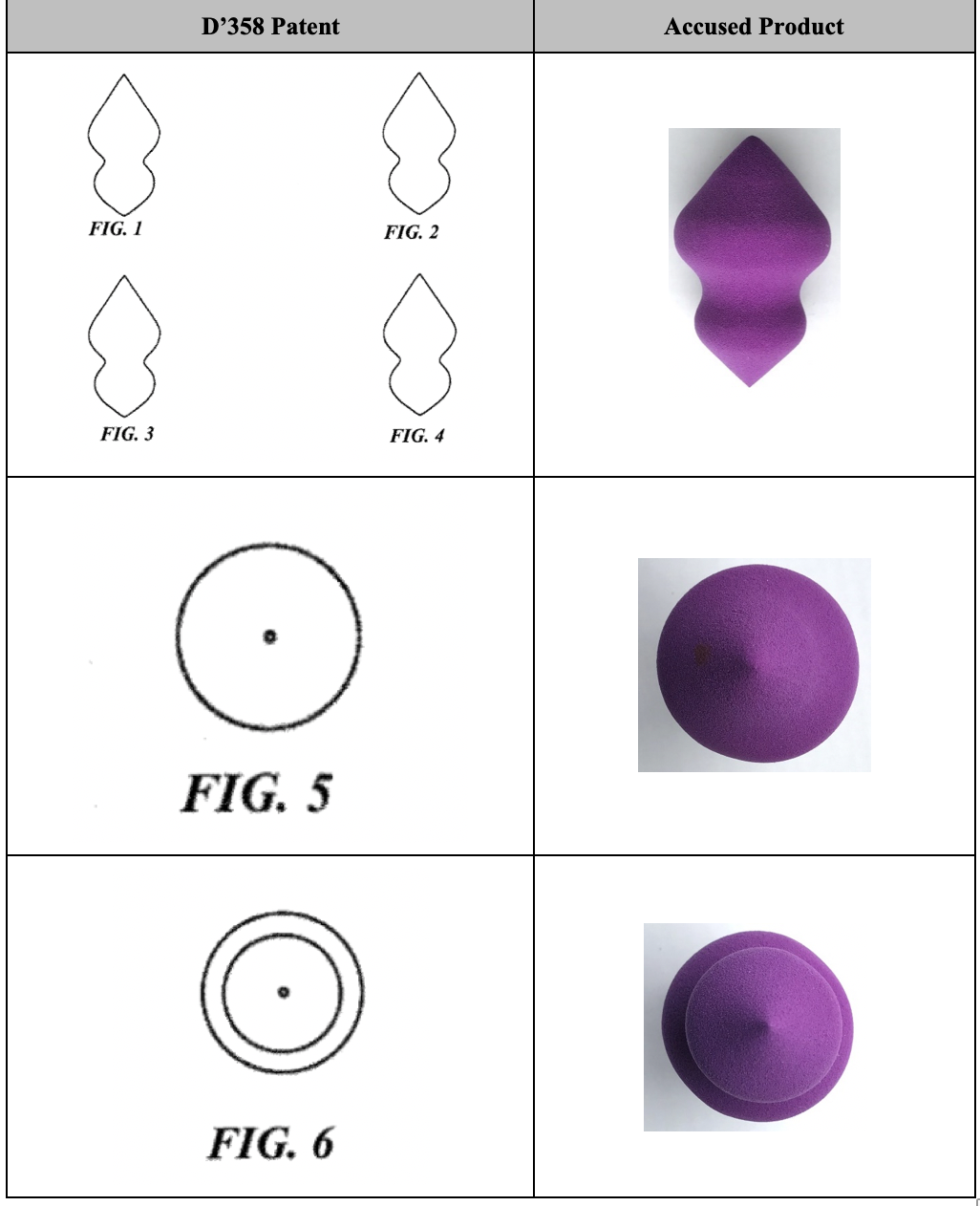

Because design patents cover ornamental designs, infringement determinations are typically relatively simple visual comparisons between the patent drawings and the accused product. In Blackbird’s face sponge litigations, for example, the accused face sponge product was compared to the drawings of the patented face sponge:

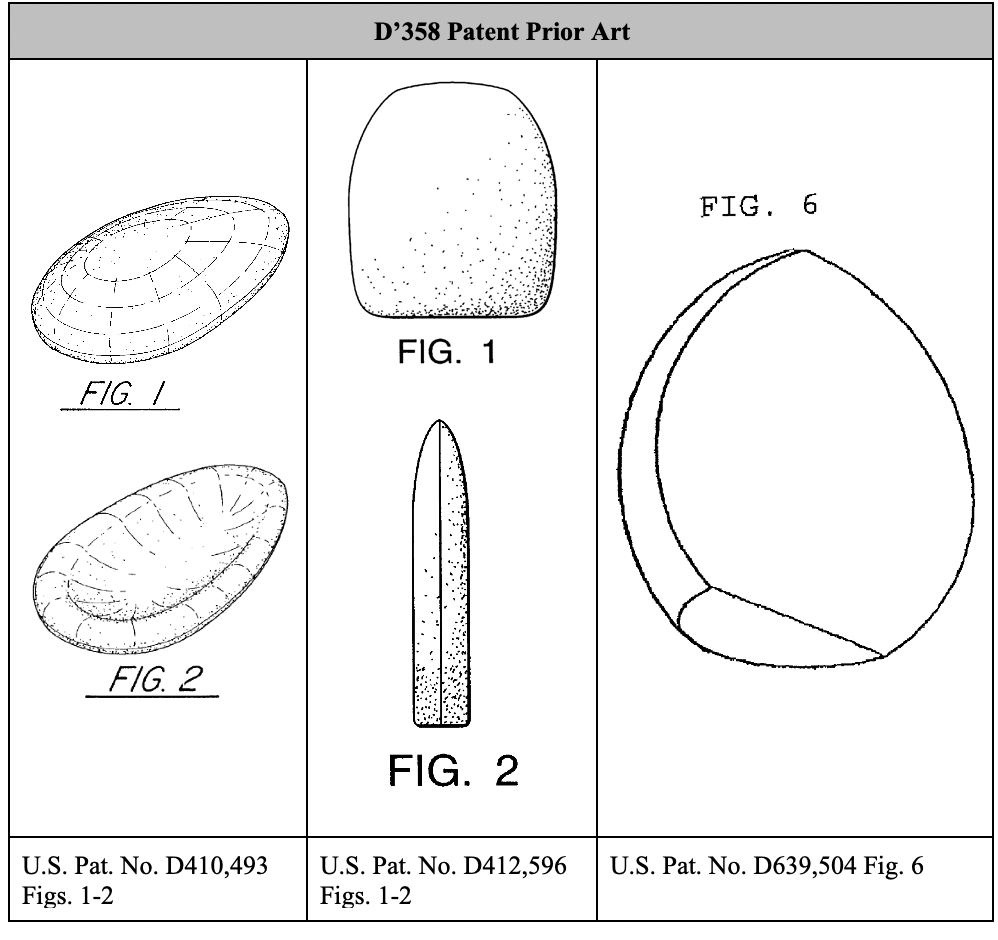

From the visual comparison alone, the similarities between the patented design and the product are evident. More, the prior art is quite different, as demonstrated by the following examples taken from the file history:

Taken together, an ordinary observer familiar with the prior art should find that the accused product infringes the D’358 patent.

Simple and Generous Damages

The Patent Act provides that infringers of both design and utility patents are liable for “adequate compensation” to the patent holder that is “in no event less than a reasonable royalty.” What constitutes a “reasonable royalty” is invariably a point of stark disagreement between parties to a litigation and typically represents competing damages experts’ opinions regarding a “hypothetical negotiation” for a license — what a willing patent licensee would have paid a willing licensor in an arms-length negotiation at the time infringement began.

This “hypothetical negotiation” inquiry is typically conducted by painstakingly analyzing the 15 Georgia Pacific factors. This includes considerations such as the royalties of prior licenses to the patent(s) at issue or licenses the infringer has taken to comparable patents, as well as the portion of the infringer’s profit attributable to the patented invention. As should be readily apparent, the calculation of a reasonable royalty leaves considerable room for disagreement. As a result, the inquiry frequently serves to significantly increase the cost and complexity of litigation, while simultaneously reducing the likelihood of settlement because of uncertainty as to the amount in controversy.

While damages in the form of a reasonable royalty are available to a design patent plaintiff, the Patent Act provides for an “additional remedy for infringement of [a] design patent”: the infringer “shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit” attributable to the infringing product. In other words, the patentee is entitled to profit disgorgement. Profits are frequently both easier to calculate and significantly greater than a reasonable royalty. In fact, many infringing companies maintain product-specific profit calculations in the usual course of business.

Profit disgorgement also serves to simplify the damages analysis and reduce disagreement or ambiguity regarding the amount in controversy, which in turn can increase the likelihood of resolving a case through early and less expensive means such as mediation.

Patent-Eligible Subject Matter

The Patent Act provides that a patent may be obtained for “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” While the scope of what may receive patent protection is broad, the Supreme Court has “long held that this provision contains important implicit exceptions: laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.” These exceptions define subject matter that is not “patent eligible.”

Of these three exceptions, the courts have particularly struggled to provide clarity and predictability as to what does—and what does not—constitute an unpatentable abstract idea. Following the Supreme Court’s Alice v. CLS Bank opinion, this determination follows a two-part test: First, the court must determine whether the claims are drawn to as an abstract idea. If the answer is yes, the court must look to the elements of the claim both individually and as an ordered combination to see if there is an inventive concept.

While the inquiry may seem straightforward enough, courts at the trial and appellate level alike have tried and largely failed to provide clarity and predictability as to whether a patented concept is abstract. Indeed, the Federal Circuit found over 82% of patents analyzed for patent eligibility between the Alice decision in 2014 and late 2020 invalid as directed to patent-ineligible subject matter. It follows that, while not every utility patent is amenable to a subject matter eligibility challenge, those that are stand a significant chance of being invalidated.

Fortunately, however, the notion of patent-eligible subject matter applies only to utility patents. As a result, the enforcement of design patents avoids this potential area of dispute and attendant risk of invalidation, resulting in increased certainty for the patent holder.

Lower Likelihood of Inter Partes Review

One of the key changes made by the 2011 America Invents Act was the introduction of the inter partes review (IPR) procedure, by which the USPTO, through the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), reviews issued patents for novelty and non-obviousness based on prior patents and publications. Used by many accused infringers to obtain a second, extra-judicial bite at invalidating patents they are accused of infringing, IPRs were invalidating such a large percentage of patents that, in late 2013, then-Federal Circuit Chief Judge Randall Rader referred to the PTAB panels as “death squads killing property rights.”

While IPRs and other post grant proceedings have become commonplace in utility patent litigation, they are not commonly used for design patents. Through August 2020, the PTAB instituted IPR proceedings (the first procedural step in an IPR) in 65% of the over 9,400 IPR petitions filed on utility patents. Of the proceedings that made it all the way to a Final Written Decision (over 99% of which involved utility patents), 80% resulted in the invalidation of at least one patent claim with 62% invalidating all challenged claims. During that same eight-year time period, only 56 petitions were filed on design patents, of which only 21 (38%) were instituted.

In Sum, Design Patents Add Value

Design patents are often overlooked when it comes to both obtaining protections and ensuring that others do not infringe on those protections once obtained. Yet design patents are an effective way to strengthen the intellectual property protections for a product, whether or not that product is also subject to utility patents.

While the precise protections available under design and utility patents vary, design patents are significantly less costly to obtain and maintain and can garner increased damages. They are also easier to enforce in numerous respects, ranging from claim construction, to infringement and validity analyses, to calculating damages.

Bottom line—design patents are a valuable addition to a patent portfolio.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

7 comments so far.

ipguy

June 2, 2021 08:10 pmIf a design patent is the “Utility Patents’ Lesser-Known Cousin, ” what’s the plant patent…the Utility Patents’ Neglected Step-Sibling?

Jacek

June 1, 2021 03:33 pm” filings from outside the EU rising remorselessly”??

Should I be ashamed using EPO?

“In terms of effectiveness, the EU’s design legislation has been broadly successful in promoting a single market for products embodying designs, with the exception of provisions on design protection for component parts used for the repair of complex products. Due to only partial harmonisation, the economically important spare parts market continues to be fragmented, causing considerable legal uncertainty and distorting competition.

The legislation also proved to be effective in providing reliable protection tools, serving the needs of multiple design industries. Regarding enforcement, the evaluation revealed that,

although judicial recourse is widely used, there is room for improvement. This should be explored in the context of the recent evaluation of the Enforcement Directive3

. The Regulation has also clearly been effective in providing access to simple and affordable design protection by making it significantly easier and less costly to obtain a registered design right that is valid across the whole EU”

What is wrong with that?

What about?

Industrial product registration?

You do not have to see a lawyer. The cost is Peanuts comparing with the US and is in effect next day without 2 years delay like in the US. Plus you can register up to 100 designs in one application when in the US they are going divide it in single applications and charge you about 10 times as much after the torture dealing with examiner babbling about “judicial exemptions”

Blue Bus

June 1, 2021 10:49 amAnon, fair questions. A link below will take you to the EU Commission website. If you download the pdf and look at Fig 4 you can see the proportion of filings from outside the EU rising remorselessly, up by now to just under 40%

https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/1846-Evaluation-of-EU-legislation-on-design-protection_en

And the link below to a law firm website leads you to the EU Commission view that there is “underuse” of design patents by EU residents.

https://www.allenovery.com/en-gb/global/news-and-insights/publications/the-evolution-of-eu-design-law-what-you-need-to-know

Anon

June 1, 2021 07:16 amYou have feelings about “bulk filers,” but no examples?

Where did these feelings come from? Why would anyone give them any credibility?

(Not trying to be snarky)

Blue Bus

May 31, 2021 02:32 pmNo. Sorry. Just a general feeling about which bulk filers are most assiduous at aggregating the potent rights on offer with the EU Design Regulation.

Jacek

May 31, 2021 11:20 am” In yet another illustration of the Law of Unintended Consequences, non-EU industry has been quicker than domestic manufacturers to seize the potency of the new exclusive right and thereby put the squeeze on their European competitors.”

Hi. Can you give as real example of the squeeze?

Blue Bus

May 30, 2021 04:49 pmAlso in Europe, design patents can deliver a surprisingly large bang for surprisingly few bucks. When the politicians set up the EU Design Patent Regulation, they supposed that its high potency and cheap acquisition and enforcement costs would help domestic industry to see off competition from outside the EU. In yet another illustration of the Law of Unintended Consequences, non-EU industry has been quicker than domestic manufacturers to seize the potency of the new exclusive right and thereby put the squeeze on their European competitors.

In days gone by, industry took out design patents if at all then only in their home market. Those days are long gone, as the politicians in Europe are belatedly realising.