“Claims may lack written description support even if a specification includes explicit disclosures…. More recently, patent owners have fared poorly when trying to enforce claims directed toward ‘effective’ treatments.”

There is a quid pro quo under the U.S. patent laws. In exchange for disclosing her invention, an inventor receives a limited monopoly. Recent developments, however, have made it harder for those in the biotechnology industry to obtain the benefit of this bargain. The written description requirement mandates that a patent specification convey to one of skill in the art that the inventors had possession of their invention as of the day they filed their patent application. Ariad Pharms., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2010). Over the last decade, three areas have proven troublesome in the life sciences.

There is a quid pro quo under the U.S. patent laws. In exchange for disclosing her invention, an inventor receives a limited monopoly. Recent developments, however, have made it harder for those in the biotechnology industry to obtain the benefit of this bargain. The written description requirement mandates that a patent specification convey to one of skill in the art that the inventors had possession of their invention as of the day they filed their patent application. Ariad Pharms., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2010). Over the last decade, three areas have proven troublesome in the life sciences.

Claiming Ranges

First, claiming ranges can be tricky. As the Federal Circuit has explained, disclosure of a broad range of values may not be sufficient to support a particular value within that range. The General Hospital Corp. v. Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., 888 F.3d 1368, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2018). From the patent’s disclosure, a skilled artisan must be able to discern the import of the claimed values.

Claiming Antibodies

Second, claiming antibodies has become increasingly difficult. A genus of antibodies is often claimed with reference to functional characteristics, such as antibody’s binding affinities or binding locations or blocking ability. But to adequately support a genus claim, a patent must disclose either a representative number of species, or structural features common to all members of the genus. Abbvie Deutschland GmbH & Co. v. Janssen Biotech, Inc., 759 F.3d 1285, 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2014). This can be quite a tall order.

In a dispute over a psoriatic arthritis drug, the inventors had set out sequences of over 300 antibodies in their specification. The problem, though, was that all of the disclosed antibodies had very similar sequences, “sharing 90% or more sequence similarity in the variable region[],” which is the region of an antibody that allows it to bind to a particular antigen. Though the accused antibody had the claimed neutralizing and antigen binding functions, its variable region was only 50% similar to the sequences taught in the patent. Id. at 1300. This was significant because expert testimony established that antibodies that were more similar to those in the disclosure—including those that were 80% similar through the variable region—could entirely lack the claimed functionality. The patent did not otherwise teach structural features that were common to all members of the genus. Thus, the patents were an attempt to cover every antibody that would achieve a desired result, but lacked representative examples to support the full scope of the claims.

The Lack of Written Description Trap

Third, claims may lack written description support even if a specification includes explicit disclosures. Courts will consider whether there is a cohesive disclosure that supports the claim, or whether support must be cobbled together from disparate and unrelated teachings. E.g. FWP IP ApS v. Biogen MA, Inc., 749 Fed. Appx. 969, 2018 WL 5292070 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 24, 2018).

More recently, patent owners have fared poorly when trying to enforce claims directed toward “effective” treatments. Most notably, Idenix (now part of Merck) won a $2.54 billion jury verdict against Gilead based on sales of the latter’s hepatitis C drug, only to lose the verdict on post-trial motions. On appeal, the district court’s non-enablement finding was upheld. Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Gilead Sciences Inc., 941 F.3d 1149, 1153 (Fed. Cir. 2019). Additionally, the Federal Circuit determined that the patent claims lacked written description support.

The only independent claim in the asserted patent recited:

- A method for the treatment of a hepatitis C virus infection, comprising administering an effective amount of a purine or pyrimidine ?-D-2′-methylribofuranosyl nucleoside or a phosphate thereof, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or ester thereof.

As construed, the preamble was a narrowing, functional limitation. This combined with the requirement for the administration of “an effective amount” meant that the claims only covered a subset of claimed nucleosides that actually treat hepatitis.

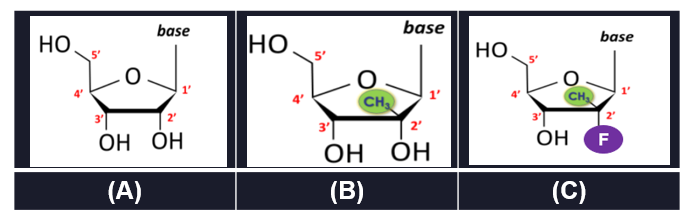

The claimed nucleoside structure corresponded to a sugar ring with five carbon atoms (numbered 1’ to 5’) and a base. (Figure 1A). At each carbon atom, additions could be made in either the “up” or the “down” positions. Idenix, for example, argued that a 2’-methyl-up nucleoside was key to treating hepatitis. (Figure 1B).

Gilead’s drug was a 2’-methyl-up nucleoside, but—unlike anything taught in the patent— it also had a fluorine in the 2’-down position. (Figure 1C). Reflecting the plain language of the claims, the court’s construction required a methyl group at the 2’-up position, but allowed for any non-hydrogen substitutes at the 2’-down position. The result? The candidate compounds numbered in “at least [the] many, many thousands,” if not on the order of millions. Id. at 1157.

The patent itself disclosed 18 different formulas. For just one formula, there were two dozen possible substituents at the 2’-up position. Additionally, there were a dozen possibilities at the 2’-down position and dozens of options at other positions in the sugar ring, not to mention multiple different options for the base. This formula alone was determined to disclose more than 7,000 unique configurations with a 2’-methyl up substitution. There was no teaching for any of the formulas as to which combination of substitutions would result in a compound effective for treating hepatitis C. Moreover, there was no teaching whatsoever of the accused structure. Nor could there have been. Patent owner’s own witness admitted that Idenix itself “only came up with” that combination a year after it had filed its patent.

Nuvo Pharmaceuticals lost its patents on a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) for a similar reason. Its claims covered compositions that included an NSAID and an acid inhibitor “present in an effective amount to raise the gastric pH of [a] patient to at least 3.5,” along with an enteric coating surrounding at least part of the acid inhibitor. Nuvo Pharmaceuticals v. Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, 923 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2019). The allegedly novel drug form had the benefit of prolonging the release of the acid inhibitor, which counteracts undesirable NSAID side-effects (such as ulcers). On defendants’ appeal, the claims were found to require that uncoated acid inhibitor be effective to raise the pH to the claimed level. The claims were also determined to be invalid for lack of written description support because there was no data in the specification to demonstrate to a POSITA that the inventors “possessed” effective, uncoated acid inhibitors.

By contrast, claims to a method for treating obesity were determined to be valid at least in part because of a “peculiarity” of the claim language. Nalpropion Pharmaceuticals v. Actavis Laboratories, 934 F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2019). Though the claims recited a treatment method—including specific steps of administering specific amounts of drug twice a day—they concluded with recitation of in vitro dissolution data. Defendant argued that the claims were invalid for lack of written description because they recited a dissolution profile achieved by one particular method, but the specification disclosed data only achievable by a different method. The district court had rejected Defendant’s argument, crediting patent owner’s expert’s testimony in determining that the patent specification disclosed two “substantially equivalent” methods for measuring dissolution. Patent owner’s win was upheld on appeal.

Pore Over the Patent

The lesson for litigants? If the asserted claims encompass an effective “treatment,” it will pay to pore over the patent specification.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:177220922

Copyright:microgen

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-banner-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-938x313-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IP-Copilot-Apr-16-2024-sidebar-700x500-scaled-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

22 comments so far.

Anon

June 15, 2021 06:32 pm…replies at 17 and 19 (not 7 and 9)

Anon

June 15, 2021 02:52 pmGreat – then my reply at 7 also stands, unaltered.

And 9 as well (you know, for that discussion of some point of information thing).

You seem to confuse whether or not “winning” can accompany conversation.

Most odd for a (supposed) attorney.

TFCFM

June 15, 2021 12:02 pm???

Whatever. My original statement (@#5) stands, unaltered.

Good luck someday having a conversation focused on discussing some point of information, instead of being focused on “winning” some inscrutable goal that only you apparently fathom.

Anon

June 14, 2021 11:03 amNot sure what ‘response’ you are waiting for. Near as I can tell the ‘conversation ball’ is still in your court.

The point should be clear that outside of your ‘favored’ (and heavily caveated) realm, the notion that innovation with function NOT linked expressly and strictly to one “structure” is something that need be integrated into your larger comments vis a vis “what was invented.”

That you were always so priggish on this very point earns me not a small level of smugness in your current growing realization that your past exchanges were based on your faulty understanding.

TFCFM

June 14, 2021 10:11 amIf you’d bother trying to respond substantively, rather than merely attempting to childishly insult others, we might someday have an actual conversation.

Anon

June 11, 2021 02:33 pmAn unusual answer from you TFCFM.

First, you appear to even try to be answering.

Second, you appear to want to use extensive caveats and pull back to a very specific art field (in contrast to your general comments on other legal items that also carry the ‘had not invented’ line.

You seem trepidatious in realizing that NOT ALL innovation has such a “lock” of specific function to specific structure.

TFCFM

June 11, 2021 11:17 amOops. Poor proofreading on my part. The following paragraph should have had the highlighted words in it:

2) My observation does not necessarily apply (surely not in precisely the same way; sometimes perhaps little or not-at-all, depending on the circumstances) in cases lacking the stringent form-follows-function link. That is, I do not intend my observation to EXTEND TO these potentially-wildly-varying situations.

(Also, in the first sentence of the next paragraph, “…situations in which function may not follow function…” should read “situations in which function may not follow structure,” but I think that typo was more obvious.)

TFCFM

June 11, 2021 11:13 amTFCFM@#5: “‘Anything and everything that performs the same function as what I actually invented’ is not an adequate written description of non-invented subject matter in any sane person’s book — particularly in subject matter like this, where function very directly follows structure.”

Anon@#6: “And what cases, TFCFM, in which function does NOT directly follow structure?”

I’m not certain I understand what you intend to ask. I understand you to question whether my observation applies equally (or less, or perhaps more) in cases in which function and structure are less concretely linked.

To clarify:

1) My observation is that in cases like this one, where function is closely tied to structure, a disclosure of only limited structure ought to limit the scope of what can be validly claimed to those structures which closely mirror the disclosed structure. Claims directed to structures substantially different from those disclosed structures are not supported by the disclosure and ought not to be granted to the applicant.

2) My observation does not necessarily apply (surely not in precisely the same way; sometimes perhaps little or not-at-all, depending on the circumstances) in cases lacking the stringent form-follows-function link. That is, I do not intend my observation to these potentially-wildly-varying situations.

There are, of course, many kinds of situations in which function may not follow function as stringently as in a protein-ligand binding situation (as in this case). Each such situation would need to be considered individually to assess whether my observation applies equally, more, or less to the particular situation. This, of course, follows from the mere reality that how our patent laws interact with particular situations varies based on the particularities of the technology(ies) and disclosure-and-claim drafting conventions corresponding to the situation.

Simply restated, my comment is that, in the field of antibodies, it’s not remotely controversial to observe that disclosure of a family of closely-structurally-related antibodies does not adequately support a patent claim to an antibody having a substantially different structure, REGARDLESS of whether or not the claimed antibody has a functionality similar to antibodies in the disclosed family. (If the claim were to a method which recited use of ‘an antibody having functionality X,’ the observation might well be different.)

Anon

June 10, 2021 04:51 pmBy the way George, any attempt by you OTHER THAN admitting your error only emphasizes your inanity.

You would simply be NOT intelligent to continue to fight my highlighting of your clear error.

Far better to own it, retract it, and then restate your ‘new’ position. Wanting me to be ‘wrong” and you (even remotely) correct is a no-win for you.

Anon

June 10, 2021 01:37 pmGeorge,

Move the goalposts back.

Your first comment was: “That’s why you can’t patent a ‘new use’ for an ‘old structure’”

You now switch to “Doesn’t say anything about a new use for an ‘old invention’ ALONE!”

Where does this ‘invention alone’ stuff come from? Are you stating that you had made an error, that my comment is 100% correct, and that you are NOW offering a different statement?

George

June 10, 2021 01:04 pm@Anon #10

35 USC 100(b)(emphasis added): The term “process” means process, art, or method, and includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.

Doesn’t say anything about a new use for an ‘old invention’ ALONE! If you just use an old invention for a different purpose you usually can’t patent that different use for the original patent (without adding to it, or subtracting something from it)!

New use ‘might be’ (see below) patentable if it satisfies all the other requirements for patent. The ‘new use’ of a ‘single old invention’ would have to be pretty surprising and not at all expected (as I stated in my comment about a wheel being used for some totally unexpected purpose). I also suggested that ‘might’ be patentable. In any case, I wouldn’t bother ever ‘trying’ to do it. In most cases it would probably be futile or at least get tons of pushback. Good luck if you want to try it. Again, I am (more) right and you are wrong!

2112.02 Process Claims [R-10.2019]

II. PROCESS OF USE CLAIMS — NEW AND NONOBVIOUS USES OF OLD STRUCTURES AND COMPOSITIONS MAY BE PATENTABLE

“The discovery of a new use for an old structure based on unknown properties of the structure might be patentable to the discoverer as a process of using. In re Hack, 245 F.2d 246, 248, 114 USPQ 161, 163 (CCPA 1957). However, when the claim recites using an old composition or structure and the “use” is directed to a result or property of that composition or structure, then the claim is anticipated. In re May, 574 F.2d 1082, 1090, 197 USPQ 601, 607 (CCPA 1978) (Claims 1 and 6, directed to a method of effecting nonaddictive analgesia (pain reduction) in animals, were found to be anticipated by the applied prior art which disclosed the same compounds for effecting analgesia but which was silent as to addiction. The court upheld the rejection and stated that the applicants had merely found a new property of the compound and such a discovery did not constitute a new use. The court went on to reverse the obviousness rejection of claims 2-5 and 7-10 which recited a process of using a new compound. The court relied on evidence showing that the nonaddictive property of the new compound was unexpected.). See also In re Tomlinson, 363 F.2d 928, 150 USPQ 623 (CCPA 1966) (The claim was directed to a process of inhibiting light degradation of polypropylene by mixing it with one of a genus of compounds, including nickel dithiocarbamate. A reference taught mixing polypropylene with nickel dithiocarbamate to lower heat degradation. The court held that the claims read on the obvious process of mixing polypropylene with the nickel dithiocarbamate and that the preamble of the claim was merely directed to the result of mixing the two materials. “While the references do not show a specific recognition of that result, its discovery by appellants is tantamount only to finding a property in the old composition.” 363 F.2d at 934, 150 USPQ at 628 (emphasis in original)).

P.S. Obviously combining ‘multiple old inventions’ for a new purpose, is the bases of all ‘new inventions’ – so not the same thing that I was talking about!

George

June 10, 2021 12:39 pm“Written Description in the Life Sciences: The Devil is in the Details”

Why isn’t that the case for Nobel Prizes too (and the career advances & prestige made possible by them)?! I bet the Nobel Prize committee wouldn’t care all that much if you ‘scribbled’ how you got to E=mc^2 on the back of an envelope (and ‘society’ wouldn’t either).

It’s time to get back to ‘rewarding people’ (one way or another) for having ‘good ideas’ – period. Patents USED TO BE one way to do that. They aren’t anymore! Patents are now almost useless and a waste of time and money (except of course for the lawyers who depend on their existence).

Anon

June 10, 2021 08:59 amGeroge,

Three more ‘stream of conscience’ posts from you with 1,729 words, and the very first thing that jumps out is how simply very wrong you are with a declaration of what is permitted under patent law.

It is this type of combined rant (into the weeds) AND clear evidence that you do not understand that which you want to preach about that impugns your credibility against ALL of your views.

To wit: “That’s why you can’t patent a ‘new use’ for an ‘old structure’”

See 35 USC 100(b)(emphasis added): The term “process” means process, art, or method, and includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.

https://mpep.uspto.gov/RDMS/MPEP/current#/current/d0e302338313.html

George

June 9, 2021 09:01 pm“Claims may lack written description support even if a specification includes explicit disclosures…. More recently, patent owners have fared poorly when trying to enforce claims directed toward ‘effective’ treatments.”

That’s the problem with ‘legal claims’! They (almost always) fail to ‘fully capture’ what the scientist/inventor is trying to explain & disclose. Even the specification can sometimes fail to completely describe what the inventor may have discovered and invented (say, based on extensive notes). Scientists and peer reviewers aren’t so ‘picky’. They can read between the lines. As long as there is a consensus (among ‘experts’) as to what an inventor was ‘trying’ to say, that should be enough. Einstein didn’t have to write a 1000 page book, to make it clear what he was saying, or the significance of what he was saying (in maybe 10 pages)! I even understood those 10 pages and their significance (as a kid)!

The problem is with our legal system, when it comes to the definition of ‘adequate descriptions’ for new ideas – not with scientists or inventors! They know what they’re talking about (and usually agree on it)!

George

June 9, 2021 08:51 pm“The reality of innovation is that there may well be many examples of innovation in which function does NOT directly “follow structure.””

That’s why you can’t patent a ‘new use’ for an ‘old structure’ (i.e. you can’t patent a new ‘use’ for a knife, or a wheel). Although it ‘might’ be possible to come up with a ‘crazy new’ use for some kind of known wheel . . . maybe??? Not sure what would happen then! Keep it a trade secret???

George

June 9, 2021 08:27 pm@Anon #4

“have always been legal instruments”

Where in the Constitution does it say these ‘instruments’ have to be approved by ‘examiners’, lawyers, judges and ‘lay juries’? Why not government employed scientists and technical experts (that would know a lot more than examiners with ‘some’ limited knowledge of contemporary science)?

Patents were supposed to be just another form of property right to be awarded by an agency of government overseen by Congress (basically the Commerce Department).

And aren’t licences ‘legal instruments’ too? Aren’t various types of Permits legal licenses? Aren’t Deeds? Mineral rights? And, aren’t guns considered ‘legal property’ under the Constitution – under ‘legal permission from the government’? So, why can’t someone ‘sue’ someone else, in order to take their guns away (by arguing they ‘weren’t properly issued’)? Why don’t courts hear ‘civil cases’ to take guns away from people, once they’ve been allowed to buy them?! Can’t the Government ‘make mistakes’ when it comes to issuing gun permits, just like they apparently do – all the time – with patents now?!

There’s nothing in the Constitution that says it’s OK for the government to ‘completely invalidate’ up to half of the patents it issues, is there? But if that’s OK now, why isn’t it OK to challenge at least half of all the gun sales in this country and deem them to have been improperly allowed? Maybe when it comes to guns, lots of mistakes are being made too, right?! Both types of ‘property’ are being conveyed by means of ‘legal and constitutional instruments’, aren’t they? So, why don’t we allow the courts to simply invalidate half or more gun permits (if challenged in ‘lengthy enough and expensive enough’ trials)? All kinds of arguments could be made for doing that too (at least I could come up with them)!

The fact is attorneys, judges & (lay) juries are not the ‘best people’ to judge the scientific or economical significance of new ideas, especially in the 21st century. Indeed it has always been society’s and history’s job to do that! Would most patent attorneys have invested early in NFTs, Bitcoin or the whole idea of ‘blockchain’ (which helps criminals hide their loot)? Would they invest in these ‘great inventions’ even now?

Lawyers & judges and (lay) juries simply don’t have the training or experience to decide who the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in our society will be. They just can’t, but that doesn’t stop them from doing it anyway! To even have a credible ‘aptitude’ for doing that, those selected for doing the ‘judging’ have to at least be highly trained scientists & engineers, if not successful entrepreneurs. No one else can really weigh in on what might be ‘significant’ or ‘not so significant’ (i.e. obvious), when it comes to very technical ideas and their disclosure (and certainly not a lay jury). If you’ve never been a quarterback (or even played football) you can’t really be a credible judge one, can you?!

So, to come full circle, lawyers and courts NEVER get involved in Nobel Prize decisions and don’t ‘even try’ to second-guess them! And, I don’t think one has EVER been retracted, either (even for potentially good reasons)! So why not? Why is that, since the ‘written description’ of what a scientist may be ‘claiming to have accomplished’ couldn’t possibly have been ‘perfectly described’ in the eyes of an attorney or a court. So, why don’t we have a bunch of lawsuits contesting the many private awards that are given out each year? Those can have big consequences for those getting them too, right? After all, a lot of money is usually awarded too, not just an honorary medal. But mistakes in ‘judging’ could have been made there too, right? There could be claims of cheating or plagiarism, right? I guess it’s because society wouldn’t approve of THAT!

So, we have to ask, why don’t scientists fight tooth & nail with each other, about who gets credit for what and what the ‘legal grounds’ for what claims are being made in science, or what the ‘meaning’ of various terminology and sentences are, or what a scientist is ‘trying to say’? Seems that scientists don’t have problems ‘understanding’ what is being said by a fellow scientist (or inventor), or what’s being claimed by them – so why do lawyers seem to have such difficulty in that? Do they have some kind of problem following simple facts, logic and dates? Or, could it be a deliberate desire ‘not to understand’ what an inventor is saying (or at least ‘trying’ to say)? Could it be due to (intentional) ignorance or a difficulty in understanding plain English (as opposed to legalize)?

In many cases even a 5th grader could understand what an invention is about and what it is claiming to be ‘new’ (compared to what came before). So, why don’t we allow 5th graders in court ‘to help explain it all’ to a judge and jury? Too easy a solution? I think I’d trust a 5th grader before a lawyer, any day, because they’re not corrupted by money (much less obsessed with it) and they don’t have secret agendas or learned to play ‘dirty’ yet. Yeah, I’d probably go with a smart 5th grader to explain an invention to me first and they think it could be good for!

================================================

The U.S. is literally THROWING AWAY 1000’s of very valuable technological innovations and advances, simply because our patent system is completely and, possibly irreparably, broken. And when I say ‘throwing away’ I don’t just mean ‘giving it away’ to competitors and other countries, I mean that by not allowing ‘strong’ patents on many things, they’re also ‘devaluing them’ to the point where many will just be ‘ignored’ (at least for a long time). We don’t want scientific & technical advancements to just ‘get ignored’ or be kept in someone’s lab notebook until they die (and even after that), just because a big company doesn’t want any competition or doesn’t want to have license new ideas not originating with them.

If a published invention disclosure never gets a patent, it becomes free for the taking. I don’t think society really wants that to be how things work. Only the rich & powerful want things to be that way (and that’s why they pressed for the AIA with help from lots of attorneys and lobbyists).

Suppress inventions and patents (by various means – including expense) and you will eventually suppress future technologies, because inventors and innovators will figure out how the game is really played and who makes all the money from paying it (hint: it’s not inventors). Inventors can only take so much (and spend so much) before they finally wise up and just STOP doing it!

We’re not going to solve any of the problems with our (antiquated) patent system if we just keep going in circles and keep arguing the ‘same things’, over and over again! Patents have to be VALID when issued – period – just like deeds or mineral rights (unless maybe an Examiner had a brain tumor or something). Patents have to be issued and PRESUMED VALID for any invention that could be significant to society or the nation! Otherwise they are just (lawyer) jokes! That’s just common sense and economics 101!

So what if some (or even many) inventors get rich in the process?! Our patent system Is SUPPOSED to work that way! It was always supposed to work that way! What changed, and WHEN did that change?! When big corporations and monopolies came along? Besides, if we wanted to improve the quality and ‘legal robustness’ of patents, we could just greatly lower the number that are issued every year and disallow ‘minor’ improvements to them as grounds for new patents, so others can’t just skirt or easily get around them (take the telephone patent for instance). Our many billionaires wouldn’t even notice the difference! Our many big corporations wouldn’t either, since it might only cost them 1% of their profits (especially if they could avoid lawsuits by just licensing what they like or need, instead of trying to steal it).

Issuing more ‘good’, ‘significant’ and ‘valid’ patents in the first place, would obviously help spread the wealth (like it used to) and create a lot more jobs (since the rich don’t create jobs anymore, anyway).

Patents, if properly issued and ‘backed up’ by the government (that issues them), will always help create new jobs and help more people become prosperous too (because why should the rich have all the fun?). So who wouldn’t want the government doing a good job of that (for a change)? Who wants more litigation and endless arguments? OK, don’t answer that!

Anon

June 9, 2021 07:53 pmHmmm,

And what cases, TFCFM, in which function does NOT directly follow structure?

I doubt that you have been around long enough, but past discussions on this blog actually leveraged the anti-patent views of P01R (IIRC, a denizen of the slash-dot/techdirt ecosystem) and pivoted off the dogma therein related to MathS – a concept different than ‘math’ and ‘applied math.’

The reality of innovation is that there may well be many examples of innovation in which function does NOT directly “follow structure.”

TFCFM

June 9, 2021 03:17 pmArticle: “In a dispute over a psoriatic arthritis drug, the inventors had set out sequences of over 300 antibodies in their specification. The problem, though, was that all of the disclosed antibodies had very similar sequences, “sharing 90% or more sequence similarity in the variable region[],” which is the region of an antibody that allows it to bind to a particular antigen. Though the accused antibody had the claimed neutralizing and antigen binding functions, its variable region was only 50% similar to the sequences taught in the patent.”

Another way of describing this “problem” is that the makers of the accused antibodies invented A DIFFERENT ANTIBODY than the ones invented by the patentee.

Not surprisingly, the court had a problem with a patent claim which covered both the antibodies which the patentee had invented AND ones the patentee had not invented.

“Anything and everything that performs the same function as what I actually invented” is not an adequate written description of non-invented subject matter in any sane person’s book — particularly in subject matter like this, where function very directly follows structure.

Anon

June 9, 2021 02:14 pmTo the point of the actual article here, I found this article very interesting as a particular viewpoint of a Pharma angle.

However, the underlying concepts – such as:

– actual possession,

– WHEN (and how) an appropriate approach with functional claiming (and the degree to which functional claiming is PURE function as opposed to some vast middle ground of a recognized medium that can be molded — easily — to be functional), and

– when simply WANTING a result (and maybe, just maybe a research plan to winnow through possibilities to actually arrive at things that DO have the desired function)

collide with the patent process.

I have noted previously that actual possession is very much a problem in the Pharma world – as witnessed by the sheer number of FDA process failures.

I have noted previously that “effective” without actually possessing this — at the time of filing — seems to get a ‘free pass’ because “medicine affects human life” – except for the FACT that patent law is by and large agnostic to the field of innovation.

I have even noted in the past that the notion that “but this is not a predictable art, and therefor we should cut some slack” is just NOT within the structure of patent law.

The admonitions here in this article actually apply to ALL areas of innovation — even though they may ‘bite’ more at the Pharma area.

That’s not because of the law – it’s because Pharma has had a somewhat ‘elitist’ view of itself, coupled with a lack of appreciation of the actual magnitude of the advance of being able to build a machine through multiple modes of “Wares.”

(it’s actually an ironic point of innovation history that the vanguard of those happening into software wanted to NOT leverage that advance, but sought to constrain the advance in attempts to leverage hardware)

Anon

June 9, 2021 10:56 amGeorge,

Your empty wagon is clattering on the uneven sidewalk.

You seem oblivious to the fact that patents have always been legal instruments.

Your opening blunders are only a noisy intro to the typical soapboxing that you want to do about a technical space that simply is not capable of doing today what you want it to do (I have given you what, almost a dozen articles now across a variety of sources pointing out current limitations?).

When you type only to ‘hear yourself,’ at the same time that you refuse to hear how you sound (with feedback such as mine), the message you send is NOT the message that you think that you are sending.

George

June 8, 2021 03:28 pmIf scientists can agree on what another scientist (or inventor) is saying – then why can’t lawyers (and who should care)? That’s the fundamental question that we should be asking ourselves now. In other words, what the hell is going on with decisions as to who gets or doesn’t get a patent in this country?! It’s really not ‘rocket science’. In most cases it just comes down to common sense, ‘facts’ and ‘dates’, that’s all. If a panel of ‘true experts’ and ‘science historians’ can agree as to who invented what and when, then all should be settled. Let’s hand back the decision as to who gets IP rights to ‘real experts’, like those who decide on who gets a Nobel Prize! Last time I checked, I don’t think any of the judges for that were lawyers! And, which is more valuable, a Nobel Prize, or the average patent (which is usually worth nothing)? The ‘logic’ is irrefutable, isn’t it? If courts and lawyers aren’t ‘necessary’ for awarding Nobel Prizes, then they shouldn’t be ‘necessary’ to award patents either. They are both prizes for essentially the same thing – creativity & discovery (and I don’t know many lawyers that are super-creative or experts on it).

George

June 8, 2021 03:12 pmSo, why doesn’t any of this matter as to who gets a Nobel Prize (or any other valuable prize)? Are lawyers and judges consulted for those too? If not, why not? Do they have any right to get so involved in decisions having to do with science & technology and who merits being recognized for advances in them? Congress was charged with creating a patent system – not for guaranteeing job employment to lawyers. Congress could have just created a purely bureaucratic & administrative agency (which it mostly was in the beginning), just like our various licensing bureaus are. You don’t have to hire a lawyer to get a licence, or even buy or sell a house.

So, why should the justice system decide who invented a new ‘scientific’ process or device first? It should be up to the scientific and technical community (and society) to do that. After all, we’re talking about people’s reputations and careers, and if the PTO (or the courts) gets that wrong (because they don’t understand the science or the technology or think they know better), it could spell professional and economic ruin! It could even spell disaster for the U.S. economy (if American inventions are ‘given’ to the Chinese for free, because they are denied patent protection)!

Quibbling about ‘language’ and ‘terminology’ shouldn’t get in the way of brilliant people getting the IP protection they deserve and I bet the Founders didn’t want that either! Why would they have? They wanted to help ‘promote’ science & the useful arts and encourage progress and economic growth, not hinder it! They wanted to ‘reward’ those who made advances in science & technology (not lawyers). I don’t think the Framers really gave a crap about lawyers (even though many of them were lawyers). I don’t think that’s what they intended for the patent system. I think it was supposed to be just another property rights agency of government – to be headed and led by bureaucrats.

The Founders didn’t care if inventors would be able to express themselves perfectly, or in so clearly a way that every lawyer in the nation would congratulate them on their linguistic abilities (which scientists and engineers are not always known for and which lawyers would NEVER agree on).

That’s why all of this needs to be turned over to computers now – because they will just uncover the facts, stick to the facts, and not get (intentionally) stuck in inextricable ‘linguistic quicksand’, designed solely to keep lawyers employed and ‘swimming in dough’ – while our ‘irreplaceable’ inventors get the shaft.