“A patentee can now present a willfulness claim using a totality-of-the-circumstances approach under a preponderance evidentiary standard. Since Halo, however, the Federal Circuit’s views on what ‘willful’ means lack consistency.”

On June 13, 2016, the Supreme Court decided Halo Elecs., Inc. v. Pulse Elecs., Inc., addressing standards for recovery of enhanced damages for patent infringement pursuant to Section 284 of the Patent Act, under which a “court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed.” In Halo, the Supreme Court rejected damages-related requirements imposed by In re Seagate Tech., LLC, a 2007 decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

On June 13, 2016, the Supreme Court decided Halo Elecs., Inc. v. Pulse Elecs., Inc., addressing standards for recovery of enhanced damages for patent infringement pursuant to Section 284 of the Patent Act, under which a “court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed.” In Halo, the Supreme Court rejected damages-related requirements imposed by In re Seagate Tech., LLC, a 2007 decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

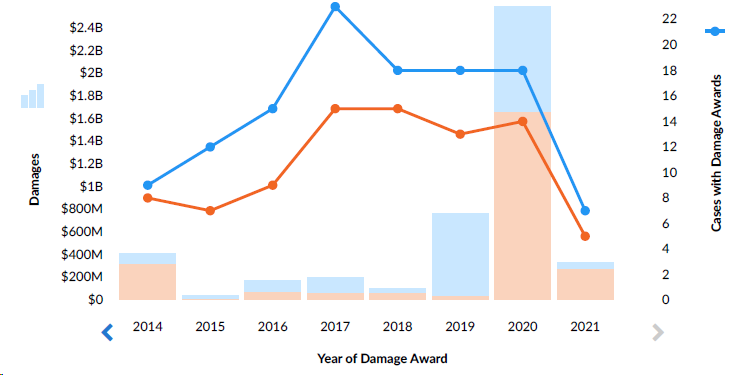

With patentee litigants freed from what the Supreme Court called Seagate’s “inelastic constraints” in favor of a totality-of-circumstances approach, a consensus developed that Halo would facilitate recovery of enhanced damages. Statistics suggest alignment with that view. The orange line in the graph below indicates that, for completed post-Halo years, 15 judgments for enhanced patent damages issued in each of 2017 and 2018, 13 in 2019, and 14 in 2020. Those totals markedly exceed the 7, 6, and 8 enhancement judgments reported for 2014, 2015, and 2016, respectively.

“Reprinted from Lex Machina with permission. Copyright 2021 LexisNexis. All rights reserved.

Yet Halo generated new questions. How does one now plead a willful infringement claim? Did Halo resurrect opinions of counsel as a hedge against willfulness claims? If so, how does that resurrection square with 35 U.S.C. § 298, which bars patentees from arguing that the absence of such opinions indicates willfulness? Recent post-Halo cases address such questions, though courts remain divided on another question – whether post-suit knowledge can predicate a willfulness claim.

Halo’s Main Holdings

The Supreme Court disagreed with Seagate’s threshold requirement that the patentee prove “objectively reckless” conduct by the infringer, which had allowed the infringer to escape a willfulness finding by advancing a reasonable defense at trial. The Court observed that Section 284 “contains no explicit limit or condition” on exercise of discretion by the trial court. It further faulted this Seagate requirement because “[t]he existence of such a defense insulates the infringer from enhanced damages, even if he did not act on the basis of the defense or was even aware of it.” Thus, the Court announced that subjective willfulness alone could predicate an award of enhanced damages, with “culpability [ ] generally measured against the knowledge of the actor at the time of the challenged conduct.”

The Federal Circuit’s requirement (in Seagate and in preceding Federal Circuit decisions) that the patentee prove willfulness by clear and convincing evidence also troubled the Halo Court. The Court noted that Section 284 omits mention of any specific evidentiary burden. It continued: “[N]othing in historical practice supports a heightened standard.” The Court quoted its Octane Fitness decision concerning recovery of attorney’s fees under the Patent Act, there stating that “patent-infringement litigation has always been governed by a preponderance of the evidence standard.” Added the Halo Court: “Enhanced damages are no exception.”

Halo “eschew[ed] any rigid formula for awarding enhanced damages under §284,” but announced that “such punishment should generally be reserved for egregious cases typified by willful misconduct.”

Willfulness and Enhancement Analytical Frameworks Resulting from Halo

A patentee can now present a willfulness claim using a totality-of-the-circumstances approach under a preponderance evidentiary standard. Since Halo, however, the Federal Circuit’s views on what “willful” means lack consistency.

- In SRI Int’l, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., a 2019 opinion modified on other grounds, the Federal Circuit remarked that a showing of willfulness under Halo requires the patentee to prove that the infringer committed misconduct that “rose to the level of wanton, malicious, and bad-faith behavior.” This requirement arguably stems from Halo’s characterization of enhanced damages under Section 284 “as a ‘punitive’ or ‘vindictive’ sanction for egregious infringement behavior.” Halo, however, did not define “willful” this narrowly.

- In Eko Brands, LLC v. Adrian Rivera Maynez Enters. (2020), the Federal Circuit remarked: “Under Halo, the concept of ‘willfulness’ requires a jury to find no more than deliberate or intentional infringement.” This quote reflects Halo more faithfully than does SRI, and it harmonizes with a district court’s recent formulation of post-Halo willfulness pleading requirements (see block quote below).

In WBIP, LLC v. Kohler Co., a post-Halo 2016 decision, the Federal Circuit reiterated: “Knowledge of the patent alleged to be willfully infringed continues to be a prerequisite to enhanced damages.” The patentee’s “totality of the circumstances” evidence must therefore include proof of such knowledge. Such proof, though meeting that prerequisite, will not by itself establish willfulness (see Justice Breyer’s concurring opinion in Halo). In a post-SRI 2019 opinion, the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware allowed patentees to establish knowledge by proving “willful blindness,” distilling pleading requirements for seeking enhanced damages as follows:

And since the doctrine of willful blindness applies in patent cases, see Global-Tech [Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A.], 563 U.S. [754,] 766 [(2011)], a willful infringement-based claim for enhanced damages survives a motion to dismiss if it alleges facts from which it can be plausibly inferred that the party accused of infringement (1) had knowledge of or was willfully blind to the existence of the asserted patent and (2) had knowledge of or was willfully blind to the fact that the party’s alleged conduct constituted, induced, or contributed to infringement of the asserted patent.

If the patentee’s willfulness claim survives pre-trial challenges, then the finder of fact (i.e., the jury in jury cases) decides whether the infringement was willful. As an example of factors considered, Eko evaluated a willfulness jury instruction telling the jury to “consider all the facts” that “may include, but are not limited to”:

(1) Whether or not ARM intentionally copied a product of Eko that is covered by the Eko 855 patent;

(2) Whether or not ARM reasonably believed it did not infringe or that the patent was invalid;

(3) Whether or not ARM made a good-faith effort to avoid infringing the Eko 855 patent, for example, whether ARM attempted to design around the 855 patent; and

(4) Whether or not ARM tried to cover up its infringement.

The Eko litigants patterned the above jury instruction on the Federal Circuit Bar Association’s (“FCBA”) National Patent Jury Instructions (“NPJI”) No. 4.1 (now No. 3.10) for willful infringement. The Federal Circuit cautioned: “There is no claim that the FCBA model instructions are afforded special status, nor could there be, since these instructions have not been endorsed or approved by this court.” The Federal Circuit did not, however, criticize the portion of the jury instruction listing factors (1)-(4) above, remarking that “the latter half of Jury Instruction 40 provides a list of facts that the jury could properly consider.” As a result, the listing of factors in NPJI 3.10 should provide useful guidance to patentees as to what kinds of facts can viably support a willfulness claim.

If the fact-finder reaches a conclusion of willful infringement, then, upon a post-trial motion by the patentee for enhanced damages under Section 284, “the issue of punishment by enhancement is for the court and not the jury.” (Eko). Halo reiterated that a judge could even deny an award of enhanced damages altogether despite a fact-finder’s willfulness conclusion.

In exercising his/her discretion when undertaking an enhancement analysis, a judge “consider[s] the particular circumstances of the case to determine whether it is egregious,” as stated in Presidio Components, Inc. v. Am. Tech. Ceramics Corp. (2017). Judges traditionally apply a 9-factor enhancement test first announced in 1992 by Read Corp. v. Portec, Inc., though Presidio held that Halo did not require application of the Read factors. Nevertheless, the Federal Circuit in Polara Eng’g Inc. v. Campbell Co. (2018) reiterated that the judge “‘is obligated to explain the basis for the award, particularly where the maximum amount is imposed’” (quoting Read Corp.).

Renewed Relevance of Opinion Letters to Combat Willfulness Claims

Commentators, including one in May 2017 hailing Halo as a “game changer,” accurately observed that the Supreme Court’s rejection of Seagate restored the strategic importance of opinion letters in attempting to avoid enhanced damages. Subsequent decisions solidify that viewpoint.

In September 2017, on remand of the Halo case following the Supreme Court’s opinion, the U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada denied Halo’s motion for enhanced damages. It viewed two opinion letters of noninfringement and invalidity as “powerful evidence that Pulse was not intentionally infringing Halo’s patent.”

In Omega Patents, LLC v. CalAmp Corp. (2019), the Federal Circuit left little room for doubt on the relevance of opinions of counsel in willfulness determinations, declaring: “As to willfulness, an accused infringer’s reliance on an opinion of counsel regarding noninfringement or invalidity of the asserted patent remains relevant to the infringer’s state of mind post-Halo.” However, if the accused infringer knew of the asserted patent before the filing of the lawsuit, any opinion may only be relevant if it was obtained at that time, as the Federal Circuit added: “Bailey’s written opinions to CalAmp after the current suit was filed were appropriately excluded since they were not contemporaneous with the infringing activity.”

In C R Bard Inc. v. AngioDynamics, Inc. (2020), the Federal Circuit stressed that an invalidity opinion, while a relevant willfulness determination factor, “was not dispositive, and the question of whether [the accused infringer] reasonably believed that the asserted claims were invalid was a question of fact for the jury.”

Although an opinion of counsel once again factors in a willfulness determination, the absence of such an opinion does not. Section 298 of the Patent Act provides:

The failure of an infringer to obtain the advice of counsel with respect to any allegedly infringed patent, or the failure of the infringer to present such advice to the court or jury, may not be used to prove that the accused infringer willfully infringed the patent or that the infringer intended to induce infringement of the patent.

In SRI, the Federal Circuit characterized an accused infringer’s decision to not seek an opinion of counsel as “legally irrelevant under 35 U.S.C. § 298.” A 2020 district court decision echoing that quote refused to accord such facts any weight in opposition to a successful motion for summary judgment of no willful infringement.

As judicially recognized, despite Section 298’s impact upon a fact-finder’s willfulness determination, Section 298 does not bar a judge from considering the absence of an opinion of counsel in his/her enhancement determination. Post-Halo, courts continue to regard such absence as relevant to Read factor #2 (“whether the infringer . . . investigated the scope of the patent and formed a good-faith belief that it was invalid or that it was not infringed”). For example, en route to doubling damages awarded under Section 284, a 2018 district court decision (Alfred E. Mann) discussing that Read factor observed: “It is also undisputed that [the defendant] did not rely on the advice of counsel in developing a good-faith belief of non-infringement.”

Courts Split on Whether Post-Suit Knowledge Counts Toward Willfulness

In March 2021, the District of Delaware observed: “District courts across the country are divided over whether a defendant must have the knowledge necessary to sustain claims of indirect and willful infringement before the filing of the lawsuit,” and that “[n]either the Federal Circuit nor the Supreme Court has addressed the issue.”

Since a court can consider a wider array of circumstances in enhancement determinations than in willfulness determinations (see the Halo remand), weighing post-suit activities in this context has apparently not spurred controversy. A late-2016 Northern District of New York decision, as well as Alfred E. Mann, assessed a Read factor focusing on “the duration of the misconduct,” and held that “continuing to sell the infringing products after notice of infringement and during the course of litigation supports enhancement.”

As post-Halo jurisprudence continues to evolve, it will be interesting to observe whether either the Federal Circuit or the Supreme Court will resolve the current split of authority on post-suit knowledge in willfulness determinations, and whether we will continue to see judgments of enhanced damages at numbers remaining above pre-2017 levels.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:59987909

Copyright:absurdov

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

4 comments so far.

Anonymous

June 14, 2021 03:47 pmJosh @2, exactly right. Opinion work is profitable for patent attorneys, and the “right” opinion can always be bought, especially since it is sold as insurance against treble damages. When is the last time ANY patent attorney wrote an opinion against the position the client wanted to hear? Any “bad” opinion is delivered orally, if ever, and the case settled.

We should be seeing enhanced damages awards far more often, and using greater multipliers, especially against serial infringers like Apple. Apple’s willful infringement is part of its very business model and has been adjudicated on many occasions.

For the scholars (and/or Congress, who is tasked with investigating anti-competitive conduct) – I challenge one of you to document and write a comprehensive article about all of Apple’s infringement, including those where willfulness was found.

Just as Telebrands misbehaved in Mr. Malone’s Tinnus case, Apple’s bad business behavior is well known by the courts and needs to be addressed with 3x enhanced damages awards.

Gabe Sukman

June 14, 2021 03:51 amThe ambiguity around post-suit knowledge will likely not amount to much, whichever way it is decided.

If a patentee is relying on post-suit knowledge for willfulness, it’s already a weak case. Even if post-suit knowledge is sufficient to defeat a motion to dismiss, it will most likely not result in enhanced damages because at that time opinion of counsel or other good faith investigation would have entered the calculus and, as Michael already noted, those investigations represent the strongest method to defeat enhanced damages (under Read Factor #2). There would have to be some pretty serious litigation misconduct for enhanced damages to be based solely on post-suit knowledge.

The biggest ambiguity that I see post-Halo is around the Arctic Cat issue that was denied cert a couple years ago: https://blog.clearstoneip.com/arctic-cat-v-bombardier-at-the-supreme-court-willful-infringement/ (follow-up here: https://blog.clearstoneip.com/supreme-court-denies-cert-in-arctic-cat-willful-infringement/).

That is, whether willfulness amounts to a negligence or recklessness standard, and whether a duty of care exists for investigating the likelihood of infringement. Between Seagate and Halo, the Supreme Court held that a patentee must show that the infringer acted despite a risk of infringement that “was either known or so obvious that it should have been known.”

What does it mean that the risk “should have been known”??

Josh Malone

June 13, 2021 10:50 pmI don’t see why an attorney opinion should carry any weight. They will ALWAYS say a patent is not infringed, ineligible, invalid, and not enforceable if the infringer pays them for such an opinion.

For those who are interested to see how this plays out, here is the analysis from our 2017 judgment. It netted a 2X enhancement. I think the infringer has to kill someone to get treble damages.

https://www.scribd.com/document/511687366/EDTX-6-16-cv-00033-725

Pro Say

June 13, 2021 06:05 pm“Since Halo, however, the Federal Circuit’s views on what “willful” means lack consistency.”

Bringing to one’s mind:

Since Alice, however, the Federal Circuit’s views on what “abstract” means lack consistency.

Rendering “CAFC consistency” . . . one big oxymoron.

Indeed.