“The First Circuit noted that Reid was not intervening Supreme Court precedent, as Forward was decided four years after Reid, and added that ‘we are skeptical that the Supreme Court, in construing the 1976 Act, casually and implicitly did away with a well-established test under a different Act.’”

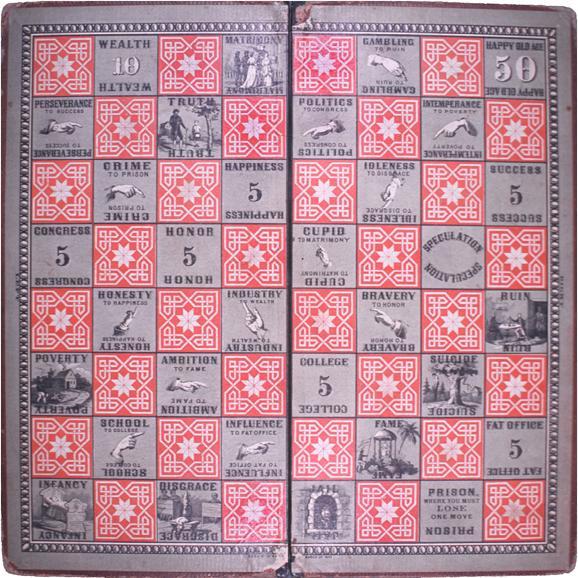

The Checkered Game of Life

On June 14, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit issued a decision in Markham Concepts, Inc. v. Hasbro, Inc. affirming a lower court’s ruling that the game design firm that developed classic board game, “The Game of Life,” possessed no termination rights in Hasbro’s copyright to that game. In so ruling, the First Circuit reiterated that the “instance and expense” test to analyze work for hire status applies to works governed by the Copyright Act of 1909, and found that the district court properly applied that test in determining that Markham’s successors-in-interest had no termination rights.

Dispute Over Creation of ‘The Game of Life’ Centers on Work Made for Hire Analysis

The present appeal stems from a long-time dispute between individuals claim credit for creating the famed Milton Bradley board game: Reuben Klamer, a toy developer who had been asked by Milton Bradley to create a game for the company’s centennial celebration in 1960; and Bill Markham, the head of a game design firm Klamer chose to develop the concept for The Game of Life, which Klamer conceived as a modern update to Bradley’s 1860 game “The Checkered Game of Life” (see image above). After successors-in-interest to Markham, who passed away in 1993, asserted the right to terminate copyright held by Hasbro and successors-in-interest to Art Linkletter, who owned a firm called Link Research that marketed the game, the District of Rhode Island ruled in 2019 that Markham’s contributions to The Game of Life met the “work for hire” exemption for termination rights under 17 U.S.C. § 304.

The First Circuit’s decision recites much of the doctrinal background of work for hire tests going back to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1903 copyright decision in Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co.; this case’s holding on employer ownership of employee works was later codified into U.S. copyright law through passage of the 1909 Copyright Act. However, this law didn’t define the terms “employer” or “work made for hire” so courts developed tests to determine works created within the scope of an employer-employee relationship until passage of the Copyright Act of 1976, which created a two-part framework covering both conventional employee relationships as well as independent contractor situations.

Significantly, Congress’s new approach was friendlier to commissioned parties than under the 1909 Act, at least in certain ways. In the absence of an employee-employer relationship, only specific kinds of works could be treated as works for hire, and then only if there was a written agreement to do so.

On appeal, Markham argued that the district court erred by applying the instance and expense test, which governed work for hire analysis for works governed under the 1909 Copyright Act. Markham contended that the test no longer applies to commissioned works under the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1989 decision in Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid. In that case, the Court held that the definition of the term “work made for hire” within the meaning of the Copyright Act of 1976 should “be understood in light of the general common law of agency.” Markham had argued that Reid’s reasoning applied to works governed by the 1909 Act, including The Game of Life, such that the instance and expense test only exempts works created under a traditional employer-employee relationship as defined by agency law.

Reid is Not Intervening Precedent, Instance and Expense Test Applies to 1909 Copyright Act Works

The First Circuit rejected this argument under its own binding precedent in Forward v. Thorogood (1993), in which the appellate court applied the instance and expense test to determine copyright ownership to unpublished tape recordings of George Thorogood and the Destroyers from recording sessions paid for and arranged by a fan of Thorogood’s music; those recordings were also governed by the 1909 Copyright Act.

Applying the instance and expense test… [t]he panel found that the evidence supported the district court’s conclusion that ‘although Forward booked and paid for the studio time, he neither employed nor commissioned the band members nor did he compensate or agree to compensate them.’ In short, ‘Forward was a fan and friend who fostered [the band’s] effort [to secure a record contract], not the Archbishop of Saltzburg [sic] commissioning works by Mozart.’ Put simply, Forward applied the instance and expense test to reach the outcome it did.

The court further noted that Reid was not intervening Supreme Court precedent, as Forward was decided four years after Reid, and added that “we are skeptical that the Supreme Court, in construing the 1976 Act, casually and implicitly did away with a well-established test under a different Act.”

Applying the instance and expense test, the First Circuit found that the evidence amply supported the district court’s finding that The Game of Life was created at the expense of Klamer, who promised to pay Markham for any costs incurred, regardless if Milton Bradley liked the game prototype, and ultimately paid for the rights. Markham argued that the game was actually made at Bradley’s expense, but the First Circuit found that Klamer bore the expense and the primary risk during the relevant time period when the prototype was being developed. Although Markham was paid in the form of a royalty, the First Circuit construed the form of payment from Klamer to Markham as the payment of a non-refundable sum certain plus a running royalty and not a pure royalty deal that would have weighed in favor of Markham having termination rights.

Although the existence of an agreement assigning rights in a work can rebut the presumption that a work was made for hire even if created at the instance and expense of another, the First Circuit held that an agreement assigning rights in The Game of Life from Markham to Link Research didn’t reserve rights in Markham but rather operated as a failsafe for Link. “That is, it makes clear that if, contrary to expectations, Markham were entitled to the copyright in the game, he would, at Link’s request, assign it over,” the First Circuit opinion authored by Circuit Judge Kermit Victor Lipez reads. The appellate court ruled that, though the agreement referenced copyright and trademark protection that might be pursued by Markham, the language was not express contractual reservation of the copyright in the artist and thus didn’t rebut the presumption that The Game of Life was made at the instance and expense of Klamer and thus a work made for hire.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Barry Manna

June 17, 2021 12:40 pmHasbro should add a square to the board game: “Lose Copyright Case, Go Back Ten Spaces”