“It appears [from Hyatt v. Hirshfeld] that if the time between a filing of a U.S. or PCT priority application and filing of a continuing application exceeds six years, it is presumed that prosecution laches applies…. What are the potential impacts of this framework?”

Laches is an equitable defense that may be raised in a patent-related proceeding. If a defending party can show that a patent holder exhibited unreasonable delay that caused prejudice to the defending party, the patent holder may be barred by laches from asserting the right.

Laches is an equitable defense that may be raised in a patent-related proceeding. If a defending party can show that a patent holder exhibited unreasonable delay that caused prejudice to the defending party, the patent holder may be barred by laches from asserting the right.

The delay may relate to how long it took for a patent holder to file a lawsuit. Further, “prosecution laches” may bar an applicant from asserting a patent. For example:

- In 1923, the Supreme Court held that laches applied when an Applicant waited nine years before contacting the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) about a delayed issuance and further – at that time – sought to amend the claims and specification. (Woodbridge v. United States, 263 U.S. 50 (1923)).

- In 1924, the Supreme Court held that laches applied when an applicant filed a divisional application with claims identical to those in a parent – thereby provoking an interference. After the interference proceeding, the applicant added two new claims, which were held to be unenforceable. (Webster Elec. Co. v. Splitdorf Elec. Co., 264 U.S. 463 (1924)).

- In 2002, the Federal Circuit held that laches applied when an applicant filed 12 continuation applications instead of arguing rejections or amending claims. (In re Bogese, 303 F.3d 1362, 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2002)).

- In 2005, the Federal Circuit provided three examples of reasonable delay: (1) filing a divisional application as late as right before a parent application’s issuance; (2) refiling an application to present new evidence of non-obviousness; and (3) refiling an application to include additional content to support broader claims. Meanwhile, an example provided of unreasonable delay was repeatedly “refiling an application solely containing previously allowed claims for the business purpose of delaying their issuance” (Symbol Techs., Inc. v. Lemelson Med., Educ. & Research Found., LP, 422 F.3d 1378, 1385 (Fed. Cir. 2005)).

While the examples of “reasonable” and “unreasonable” delay provided in Symbol Techs. are informative (as are the fact-specific analyses from the other cases), a bright-line test for “unreasonable delay” had yet to be established in the prosecution laches context. That is, until the June 2021 decision of Gil Hyatt v. Hirshfeld (Fed. Cir. 2021). This case pertained to the laches defense raised by the USPTO when Hyatt filed an action under 35 U.S.C. § 145 to obtain four patents subsequent to receiving an affirmance of rejections of various claims at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

Specifics of this case are summarized here, but the present article focuses on two sentences from the decision:

In the context of laches, we have held that a delay of more than six years raises a “presumption that it is unreasonable, inexcusable, and prejudicial.” Wanlass v. Gen. Elec. Co., 148 F.3d 1334, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 1998). That presumption shifts the burden to the patentee to prove that “either the patentee’s delay was reasonable or excusable under the circumstances or the defendant suffered neither economic nor evidentiary prejudice.” Id. (Emphasis added.)

Thus, the Federal Circuit relied upon Wanlass for supporting the presumption that laches applies when a delay of more than six years has occurred. In Wanlass, the patent holder initially approached General Electric (GE) about licensing the patent in the year that the patent issued and GE replied that they did not believe that the patented technology was new. Eighteen years after issuance of the patent, the patent owner sued GE for infringement (relying on tests of a GE product conducted by the patent owner 15 years after issuance of the patent). Because 35 U.S.C. 286 specifies that infringement recovery is only permitted when the infringement was committed within six years prior to filing of the complaint, the Federal Circuit defined a “critical date” as six years prior to the Complaint filing. It was held that the patent holder should have known about the infringement before this critical date, and thus, it was presumed that laches applied.

Notably, the basis for conducting an analysis in Wanlass using the six-year threshold was because a statute specifically identified this threshold as being applicable to infringement contexts. Further, the time period assessed in Wanlass is rather clearly defined: it begins when a patent holder should have known about patent infringement (a date of constructive or actual knowledge) and ends when a Complaint was filed.

In Hyatt, the Federal Circuit held that laches was presumed to apply (thereby shifting the burden to Hyatt to overcome the presumption) based on “Hyatt’s conduct—including his delay in presenting claims, his creation of an overwhelming, duplicative web of applications and claims, and his failure to cooperate with the PTO”. The alleged “delay in presenting his claims” was based on the time that elapsed between the filing dates of priority applications and the filing dates of the applications at issue (and of other applications in Hyatt’s portfolio).

Thus, it appears as though the logic behind this decision indicates that if the time between a filing of a U.S. or Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) priority application and filing of a continuing application exceeds six years, it is presumed that prosecution laches applies and that the continuing patent cannot be enforced. What are the potential impacts of this framework?

Delving Into the Data

To investigate, priority data for all U.S. patents issued in 2019 was obtained from GreyB Services. Each patent was characterized as being an “original” patent (that may claim priority to one or more provisional applications but not to any other U.S. or PCT application), a “national phase” patent (that claims priority to a PCT application but not to any non-provisional U.S. application), or a “continuing” patent (that claims priority to at least one non-provisional U.S. patent application). For each patent, an earliest priority date was defined to be the date of the earliest PCT or non-provisional U.S. application in the priority chain for national phase and continuing patents and was defined to be the filing date for the patent for original patents. The issue date and art unit were further identified.

The data set represented 354,401 patents, of which 50% were original patents, 21% were national phase patents, and 29% were continuing patents. Across all patents, the average time between the priority date and filing was 1.45 years; the average time between filing and issuance was 2.53 years; and the average time between the priority date and issuance was 3.98 years.

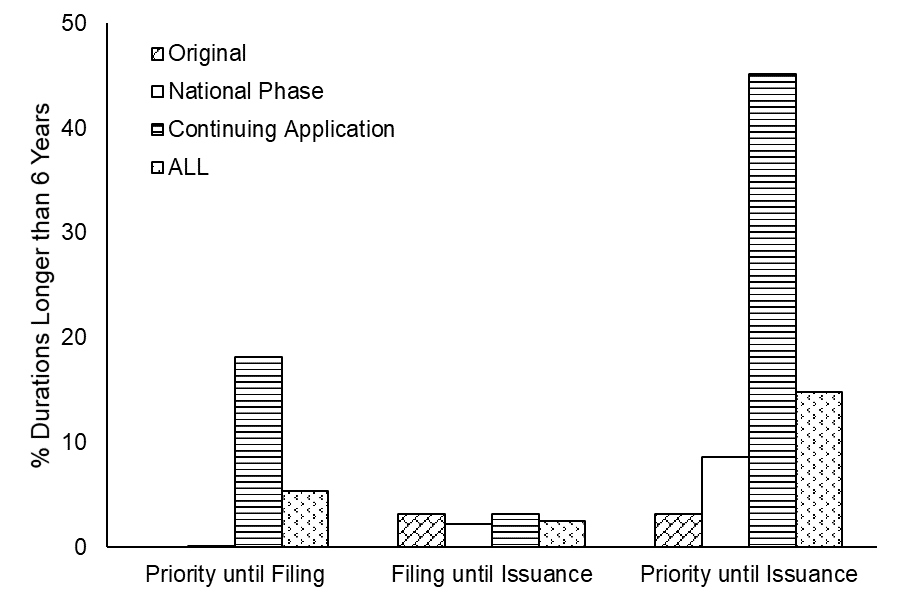

FIG. 1 shows the percentage of patents for which various time periods exceeded six years. Of highest relevance with respect to the laches-presumption analysis presented in Hyatt is the percentage of patents for which a time between a priority date and a filing date exceeded six years (which would seemingly mean are presumed to have laches apply). Unsurprisingly, none of the original or national phase patents had priority-to-filing durations that exceeded six years. However, the priority-to-filing duration did exceed six years for 18.1% or 18,858 of the continuing applications, which amounted to 5.3% of all of the patents issued in 2019.

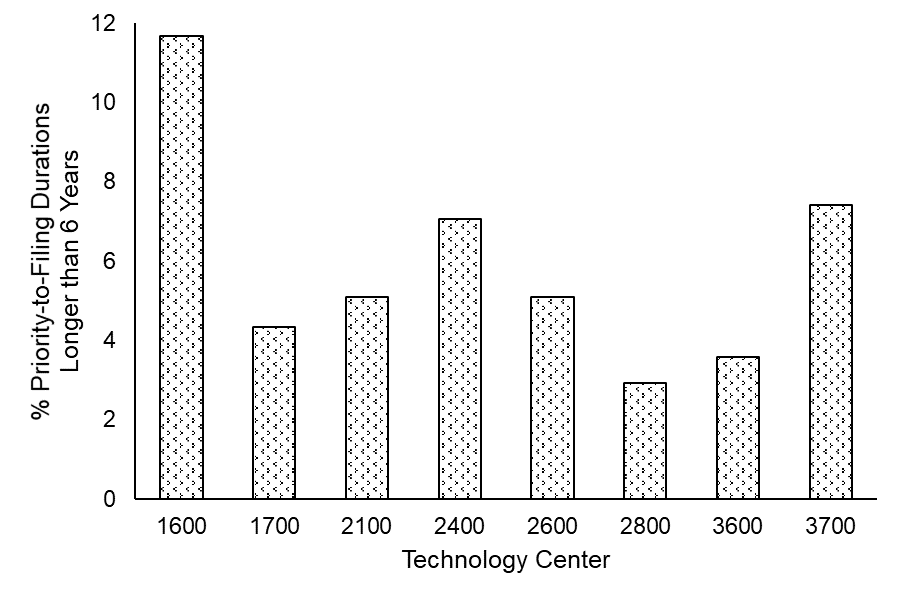

FIG. 2 shows, for each technology center, the percentage of 2019 patents with priority-to-filing durations that exceeded six years. This percentage was highest for patents from Technology Center 1600 (Biotechnology and Organic fields) at 11.7% and was lowest for patents from Technology Center 2800 (Semiconductors, Electrical and Optical Systems and Components) at 2.9%.

So, does Hyatt mean that laches is presumed to apply to 5% of patents that are issued? Bright?line rules can be very useful. However, it is important to carefully consider the potential impacts before any such rule is defined.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:50104927

Copyright:iqoncept

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

7 comments so far.

Moderate Centrist Independent

July 21, 2021 03:27 pmipguy, I think you’ve got a good point about reviving abandoned applications. I tried to revive an abandoned application for a client with a near-terminal health issue and faced a great deal of pushback on the revival.

ACD

July 19, 2021 08:45 pm“Thus, it appears as though the logic behind this decision indicates that if the time between a filing of a [] priority application and filing of a continuing application exceeds six years, it is presumed that prosecution laches applies and that the continuing patent cannot be enforced.”

Prosecution laches requires a finding of an unreasonable and unexplained delay in prosecution that constitutes an egregious misuse of the statutory patent system under the totality of the circumstances. A finding of unreasonable and unexplained delay requires a finding of prejudice. This prejudice, according to Hyatt v. Hirshfeld, is what can be presumed after 6 years. The totality of the circumstances still must show an egregious misuse. I believe it is incorrect to state that all applications filed 6 years or more after a priority application are presumed barred by prosecution laches because there still must be this egregious misuse, which is likely not going to be found simply because of filing beyond 6 years from priority.

Additionally, prosecution laches is an equitable defense. In such cases, “[a] court must look at all of the particular facts and circumstances of each case and weigh the equities of the parties.” A.C. Aukerman C. v. R.L. Chaides Const. Co., 960 F.2d 1020, 1032 (Fed. Cir. 1992). Presuming prosecution laches based solely on filing 6 years after a priority document removes this equitable consideration of the defense.

The fact specific analysis of Hyatt shows this equitable nature and the required egregious misuse.

Lastly, in my opinion, if such a presumption were indeed correct, I think it would rightfully be challenged under the Petrella/SCA Hygiene rationale. The statutory scheme gives applicants the right to file continuation and divisional applications. To some extent, the following quotation from the Supreme Court in SCA Hygiene applies:

“When Congress enacts a statute of limitations, it speaks directly to the issue of timeliness and provides a rule for determining whether a claim is timely enough to permit relief. [citation omitted] The enactment of a statute of limitations necessarily reflects a congressional decision that the timeliness of covered claims is better judged on the basis of a generally hard and fast rule rather than the sort of case-specific judicial determination that occurs when a laches defense is asserted. Therefore, applying laches within a limitations period specified by Congress would give judges a ‘legislation-overriding’ role that is beyond the Judiciary’s power.”

Pro Say

July 19, 2021 06:18 pmWhat Paul, Anon (less “reckless”), ipguy, and TFCFM said.

Paul F Morgan

July 19, 2021 03:31 pmNotwithstanding Gilbert Hyatt v. Hirshfeld (Fed. Cir. 2021), In 2017 the Supreme Court issued a 7-1 decision in SCA Hygiene Products v. First Quality Baby Products, LLC, ruling that laches—the notion that a plaintiff prejudiced a defendant by waiting too long to sue—cannot be invoked as a defense against a claim for patent infringement damages that accrued prior to the date of the suit. Explaining that a laches defense would undermine the Patent Act’s statute of limitations for damages, the Supreme Court relied heavily on its analogous copyright decision from 2014, Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., to overrule a 6-5 en banc decision from the Federal Circuit.

While this Sup. Ct. decision is on lawsuit delay laches rather than PTO application prosecution delay laches, there is now also a relevant statutory term limit – the approximately 20 years from filing date patent term [rather than the prior 17 years from indefinitely delayed issue date].

TFCFM

July 19, 2021 10:06 amArticle: “…a bright-line test for “unreasonable delay” had yet to be established in the prosecution laches context.”

It seems to me that a “bright-line test” is a little much to ask for an equitable doctrine that is supposed to take into account the particular facts and circumstances surrounding a situation for which the doctrine may be applied.

Anon

July 19, 2021 08:04 amI think that (at first blush) a blanket statement that ANY action occurring six plus years after an initial filing is not only unsupportable, but reckless.

IF (and that’s a mighty big if) there was absolutely no action, THEN the ‘six year window’ might come up in an analysis of all the facts of that situation.

But in most all instances, there is likely to be some action that would lead to a different conclusion.

For example, chain continuations may easily rely on the actions of the most prior link, and can easily extend legitimate seeking of claim coverage well past six years after an initial filing date.

ipguy

July 18, 2021 03:38 pmIt’s an interesting read but, as a practical matter, I don’t see there being much of an impact on the vast majority of applicants. I do see this as having a potentially big impact on applicants seeking to revive abandoned applications (which are already seeing higher levels of scrutiny from the PTO).