“The Third Circuit test of usefulness omits…important nuances in favor of an approach [to trademark functionality] that is overly simplistic, at odds with longstanding prior precedent, and that would have serious practical ramifications for trademark owners and consumers.” – Amicus Brief of International Trademark Association

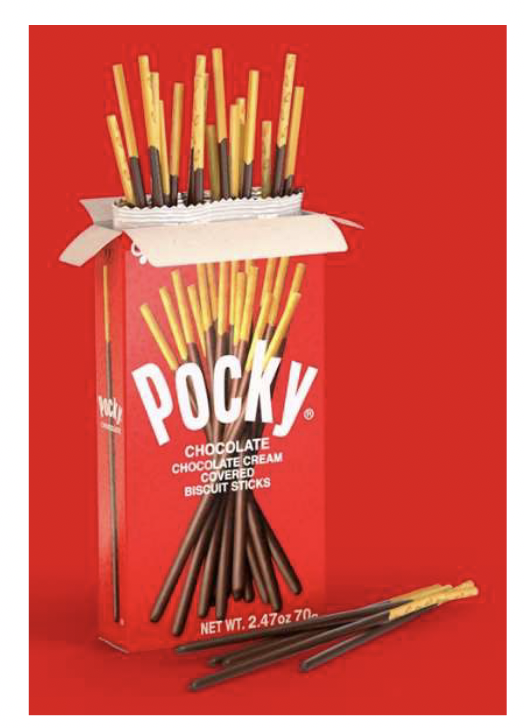

Image taken from Petition for Certiorari.

On July 29, several IP organizations and one global snack conglomerate filed amicus briefs at the U.S. Supreme Court asking the nation’s highest court to grant a petition for writ of certiorari to take up Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v. Lotte International America Corp. At issue in the appeal is a ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit regarding the definition of “functionality” in trademark law. In finding the stick-shaped, chocolate-covered Pocky cookies sold by Ezaki Glico to be “functional” because of the usefulness of their design, amici argue that the Third Circuit erred in its application of functionality doctrine in a way that threatens trade dress protections for any product when any part of the product’s design provides some usefulness.

In its decision last October, the Third Circuit held that the asserted trade dress covering the Pocky cookie, namely the uncoated cookie handle allowing consumers to enjoy the chocolate-coated portion of the cookie, was not an “arbitrary or ornamental flourish[]” but rather a utilitarian advantage that rendered the entire product functional. As a result, the Third Circuit found that Ezaki Glico held no protectable trade dress in the Pocky cookie. Ezaki Glico filed a petition with the Supreme Court in late June in which it asks the Court to rule on two questions presented:

- Whether trade dress is “functional” if it is “essential to the use or purpose of the article” or “affects the cost or quality of the article,” as this Court and nine circuit courts have held, or if it is merely “useful” and “nothing more,” as the Third Circuit held below?

- Whether the presence of alternative designs serving the same use or purpose creates a question of fact with respect to functionality, where the product’s design does not affect cost or quality and is not claimed in a utility patent?

International Trademark Association (INTA)

INTA, which supports a network of 7,200 member organizations representing trademark and brand owners across 191 countries, argues that the Third Circuit’s formulation of functionality doctrine, in which any degree of usefulness for a product feature precludes any trademark protections for that feature’s design, conflicts with more than a century of case law on functionality doctrine. INTA also contends that the Third Circuit’s decision ignored the rationale underlying functionality doctrine in trademark and trade dress law, and called into question the trademark rights for well-known products that have designs covered by registered trademarks, including Rubik’s Cubes, Square point-of-sale terminals, Herman Miller Aeron chairs and Pepperidge Farm goldfish crackers.

Pocky cookies compared to alleged infringing product.

Legal protections for non-essential elements of a product were recognized decades before passage of the Lanham Act, INTA argues, citing to the Second Circuit’s 1917 decision in Crescent Tool Co. v. Kilborn & Bishop Co. in which the appellate court held that non-essential elements of a product could receive protection if they had acquired secondary meaning identifying the product’s source. As functionality doctrine evolved, court’s recognized that the existence of alternative product designs served as evidence of non-functionality. Although the Supreme Court promulgated a simplified formulation of functionality doctrine in TrafFix Devices v. Marketing Displays (2001), in which the Court did not consider the existence of alternative designs because the asserted trade dress was previously patent protected and therefore functional, INTA argues that decision didn’t eliminate the analysis of alternative designs in the way that TrafFix was treated by the Third Circuit.

INTA points out that TrafFix Devices identifies the traditional rule for assessing functionality comes from the Supreme Court’s 1982 decision in Inwood Laboratories v. Ives Laboratories. Courts applying Inwood Labs have looked to see if a product is de facto functional, which can be protectable, or de jure functional, where no trade dress is available because the product’s design has been chosen for its functional nature.

The Third Circuit test of usefulness omits all of these important nuances in favor of an approach that is overly simplistic, at odds with longstanding prior precedent, and that would have serious practical ramifications for trademark owners and consumers. That a design feature is useful should be the beginning of the inquiry, not the end.

The Third Circuit’s overly simplistic formulation of functionality also puts it at odds with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, INTA argues, as the agency has incorporated the Inwood Labs test into trademark examination procedures. By granting the petition for writ of certiorari, INTA argues that the Supreme Court can reaffirm the importance of Inwood Labs and the longstanding test for functionality while clarifying that alternative designs are relevant to functionality but for narrow exceptions, like the existence of the utility patent in TrafFix Devices.

Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO)

IPO, an international trade association for businesses in diverse industries having an interest in intellectual property rights, also argues that the Third Circuit’s decision flouts Court precedent on functionality doctrine. Along with Inwood Labs and TrafFix Devices, IPO also cites to Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. (1995), in which the Supreme Court recognized that, in some circumstances, a color will meet legal requirements for trademark protection. IPO argues that the Third Circuit “cherry-picked” dictionary definitions for “functional” despite the fact that amendments to the Lanham Act in the late 1990s adopted the more nuanced understanding of functionality from Inwood Labs and Qualitex.

If the Third Circuit’s decision stands, IPO contends that it “would eviscerate the [Lanham] Act’s protections for every product configuration that also possesses utility.” While functionality under Inwood Labs protects trade dress while allowing competitors the ability to copy useful features, the Third Circuit’s formulation of functionality doctrine “would protect little to no trade dress, because a party would be hard-pressed to identify a product configuration that ‘does not serve any function.’” Coca-Cola bottles that are grooved for easier handling, Jeep front-end grilles with airflow slots for cooling the engine, and Weber kettle grills having a spherical shape to promote even heating are just a few examples of historically protectable trade dress that now may be unprotectable within the Third Circuit.

The distinctive elements of goods like Jeep’s grille shape, the Coca-Cola bottle’s shape, and eos lip balm’s shape and indentation, do not provide a monopoly on the underlying good. Rather, they are brand signals, immediately communicating to the consumer, for instance: “This is a bottle of Coca-Cola.”

IPO urged the Supreme Court to grant certiorari on both questions presented by Ezaki Glico, arguing that the second question on the existence of alternative designs should be granted to solve a wider circuit split on that issue.

American Intellectual Property Law Association (AIPLA)

Much like the other legal organizations filing amicus briefs in Ezaki Glico, AIPLA, a national bar association comprising 8,500 members, also argues that the Third Circuit’s decision to discard the traditional rule on functionality “decimates trade dress protection because all product design, and every feature of a product design, is ‘useful’ in some way.” While legal doctrine on functionality evolved through the courts over the course of nearly a century, AIPLA notes that the Lanham Act did not mention “functionality” until 1998 when it was codified as an enumerated defense to trademark infringement.

The decision paints with too broad a brush. By jettisoning this Court’s traditional rule in favor of an adage that ‘functional’ is ‘useful,’ the Third Circuit replaced a thoughtful balance of interests with a new standard of colloquial functionality that threatens all trade dress… No other circuit court decision since TrafFix has exalted a colloquial meaning of functionality over the traditional rule, although district courts have been reversed for this legal error.

While the second prong of the traditional rule on functionality asks courts to look at whether the asserted trade dress “affects the cost or quality” of the product, the Third Circuit discussed no cost factors. While the existence of nine alternative designs were alleged, the Third Circuit found that this evidence was “hardly dispositive” while other circuit courts have found the existence of such designs to be a genuine issue of material fact that precludes summary judgment, which was the posture of Ezaki Glico that the Third Circuit’s decision affirmed.

Further, AIPLA contends that the Third Circuit is the only circuit court to displace the traditional rule on functionality with an assessment of competitive advantage, a position that the Third Circuit adopted sua sponte without either party briefing the appellate court on that argument. AIPLA also cites to the Supreme Court’s 2000 decision in Wal-Mart Stores v. Samara Brothers, which held that product design can only be protectable if it has acquired secondary meaning as a source indicator among consumers, as well as the Tenth Circuit’s decision last August in Craft Smith v. EC Design, which AIPLA argues “exemplifies the high threshold for secondary meaning for product design trade dress.” The Third Circuit’s decision ultimately hurts consumers, AIPLA argues, as it discourages brand owners from enforcing trade dress against counterfeiters.

Mondelez Global LLC

Although other amici filings in Ezaki Glico have come from legal and bar associations, American snack conglomerate Mondel?z Global has a more personal stake in the case’s outcome. The snack company notes that several of its well-known candies and cookies, including the mountaintop design of its Toblerone chocolate bars, rely on trade dress registered with the USPTO.

If the decision of the court of appeals is permitted to stand, parties intentionally seeking to trade on the esteemed reputations and commercial magnetism of [Mondelez]’s trade dress can do so in the Third Circuit with impunity so long as they conjure an argument that the trade dress at issue is ‘useful.’ Such an argument is plainly possible with virtually any food product because food is handled, packaged, and consumed in portions or pieces.

Mondelez’s brief follows arguments that have been covered in the other amicus filings profiled here. However, the snack company elaborated upon the point that the Third Circuit’s decision to equate “functional” with “useful” improperly treats trademark law and patent law as mutually exclusive. Whereas functionality doctrine in trademark law seeks to avoid monopoly in design by eliminating protections for “best designs” that must be employed by rival firms to compete effectively, Mondelez argued that usefulness or utility in the patent context was an inquiry focused on a product’s operation and not its appearance. “Asking the patentability question of whether a product configuration is ‘useful’ fails to respect Congress’s distinct selection of the word ‘functional’ instead of ‘useful,’ and it fails to conduct the trademark functionality analysis this Court requires,” Mondelez’s brief contend

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-2024-banner-938x313-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.