“Even without asserting patents, U.S. and European patents with coordinated strategies increase the value of the patent portfolio. Accordingly, knowledge of both patent systems is critical.”

One ingredient that distinguishes a good patent portfolio from a great patent portfolio can be the synergistic strength of its U.S. and European patent family members. To develop this strength, it is not enough to have a U.S. attorney and a European attorney simply coordinate the procedural strategy for filing an application; rather, the drafter and manager of the application should analyze important issues upfront and prepare a patent application that accounts for the substantive differences between U.S. examination, U.S. courts, European examination, and national courts in Europe.

One ingredient that distinguishes a good patent portfolio from a great patent portfolio can be the synergistic strength of its U.S. and European patent family members. To develop this strength, it is not enough to have a U.S. attorney and a European attorney simply coordinate the procedural strategy for filing an application; rather, the drafter and manager of the application should analyze important issues upfront and prepare a patent application that accounts for the substantive differences between U.S. examination, U.S. courts, European examination, and national courts in Europe.

As background, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) examines and grants patents. But the USPTO does not determine whether a U.S. patent is infringed. The owner of a U.S. patent can enforce the patent against infringers by filing a civil case in U.S. federal court for patent infringement. Similar to the USPTO, the European Patent Office (EPO) examines and grants European patents, and also similar to USPTO, the EPO does not determine whether an EP patent is infringed. Rather, an owner of a European patent can “validate” the European patent in individual European countries, creating a patent recognized by the respective European country where it can be enforced through the respective national court. For example, an owner can validate a European patent in Germany to become a German patent. If the owner of such a validated patent wants to enforce the patent, they must use a national court (i.e., where the European patent is validated) for infringement proceedings. To that end, the owner of a European patent that was validated in France can enforce the French patent in French courts. Thus, a European patent gives a patent owner enforcement options in national European courts (e.g., German, French, and/or British) as long as the owner validated the European patent in that respective country.

Coordinating Strategies Across Jurisdictions

U.S. and European patents make a nice pairing when developing a litigation strategy because there can be many natural synergies. For example, U.S. litigation can be expensive and slow as compared to German litigation, but there are benefits to be gained in the United States. It is often helpful for a U.S. plaintiff to file litigation in the United States early on to gain access to more internal documents through the U.S. discovery process, then file litigation and use the speed of the German courts to drive settlement or increase pressure on the defendant. The German courts are also reasonably pro-plaintiff in granting preliminary injunctions, further increasing the potential pressure on the defendant. Also notable for national courts in Europe is that France has some of the strongest search and seizure laws for patent holders. Given these different jurisdictional options and tools, a plaintiff with patent family members in multiple jurisdictions can take advantage of different jurisdictional rules and procedures to achieve its overall goals; at the same time, a defendant should be aware of how to defend itself or prevent plaintiffs from applying pressure in multiple jurisdictions.

Further, in the next few years, the Unified Patent Court (UPC), an international court in Europe that decides on the infringement and validity of unitary patents—which can be based on EP patents (i.e., those granted by the EPO) without the need for nation-specific litigation—is expected to open. Plaintiffs interested in such central enforcement at the UPC will want to have strong European patent family members established.

Even without asserting patents, U.S. and European patents with coordinated strategies increase the value of the patent portfolio. Accordingly, knowledge of both patent systems is critical to achieve not only the goal of establishing a strong patent family in each, but also the goal of opening the door to pursue all available options, up to and including individual country-specific national patents.

While there are many ways to implement a successful strategy for establishing U.S. and European patent family members and working in concert with both systems, we will focus on three in particular: Part I of the article analyzes intervening prior art, Part II analyzes software patents, and Part III then analyzes the importance of, and strategies for, examiner interviews in both the United States and Europe. These articles will be useful for patent portfolio managers, patent attorneys, and others (including litigators) advising on patent strategy in the United States and Europe.

- Strategy for Intervening Prior Art in the United States and Europe

This section of the article discusses how patent portfolio managers should be careful when generating company-owned prior art or reviewing competitor prior art, and how a patent litigation or licensing campaign can be significantly hamstrung based on how the United States and Europe consider intervening prior art.

As background, intervening prior art is a patent application that is filed before and published after the filing date of the patent or the patent application being prosecuted—for this reason, it is sometimes referred to as “secret prior art” because it is not known to the public at the time the prosecuted application is filed. Even though intervening prior art is published after the filing date of the application being prosecuted, the EPO, national courts in Europe, the USPTO, and U.S. federal courts can still use it to reject a claim in a pending patent application or to invalidate a claim in an issued patent as explained below in this article.

Patent application drafting and litigation often starts with reviewing the prior art, but it is not common for drafters and litigators to think about intervening prior art early in the process. For example, intervening prior art under Art. 54(3) of the European Patent Convention (EPC) in Europe is considered weak because it can only be used to judge novelty, yet the same prior art can be considered very strong in the United States under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(2) because it applies to judging both novelty and obviousness in the United States. For reference, Art. 54(3) EPC prior art is a European patent application (or Patent Cooperation Treaty [PCT] application that meets the requirements of Rule 165 of the EPC) that was filed prior to the filing date of the claim but published after the filing date of the claim. European patent applications that are citable under Article 54(3) EPC are citable for novelty only and not for inventive step.

Intervening prior art in Europe is complicated because the EPO, the national European patent offices, and the national courts of European countries all consider it differently. Specifically, the EPO does not consider national patent applications (e.g., German, French, United Kingdom applications) to be intervening prior art. Rather, to qualify as intervening prior art, the intervening applications must be a European patent application. Therefore, during prosecution or during opposition procedures in front of the EPO, only EP patent applications can be used as intervening prior art. In contrast, in procedures related to an EP patent in front of an individual national court in Europe (e.g., in German Federal Court in a nullity proceeding), the plaintiff may use national patent applications as intervening prior art against the EP patent.

Even though the EPO or a national court in Europe will consider intervening patent applications to be prior art, the EPO or national court will only consider intervening prior art for judging novelty (i.e., anticipation). This is often surprising to U.S. practitioners because intervening prior art is used for judging both anticipation and obviousness by the USPTO and U.S. courts.

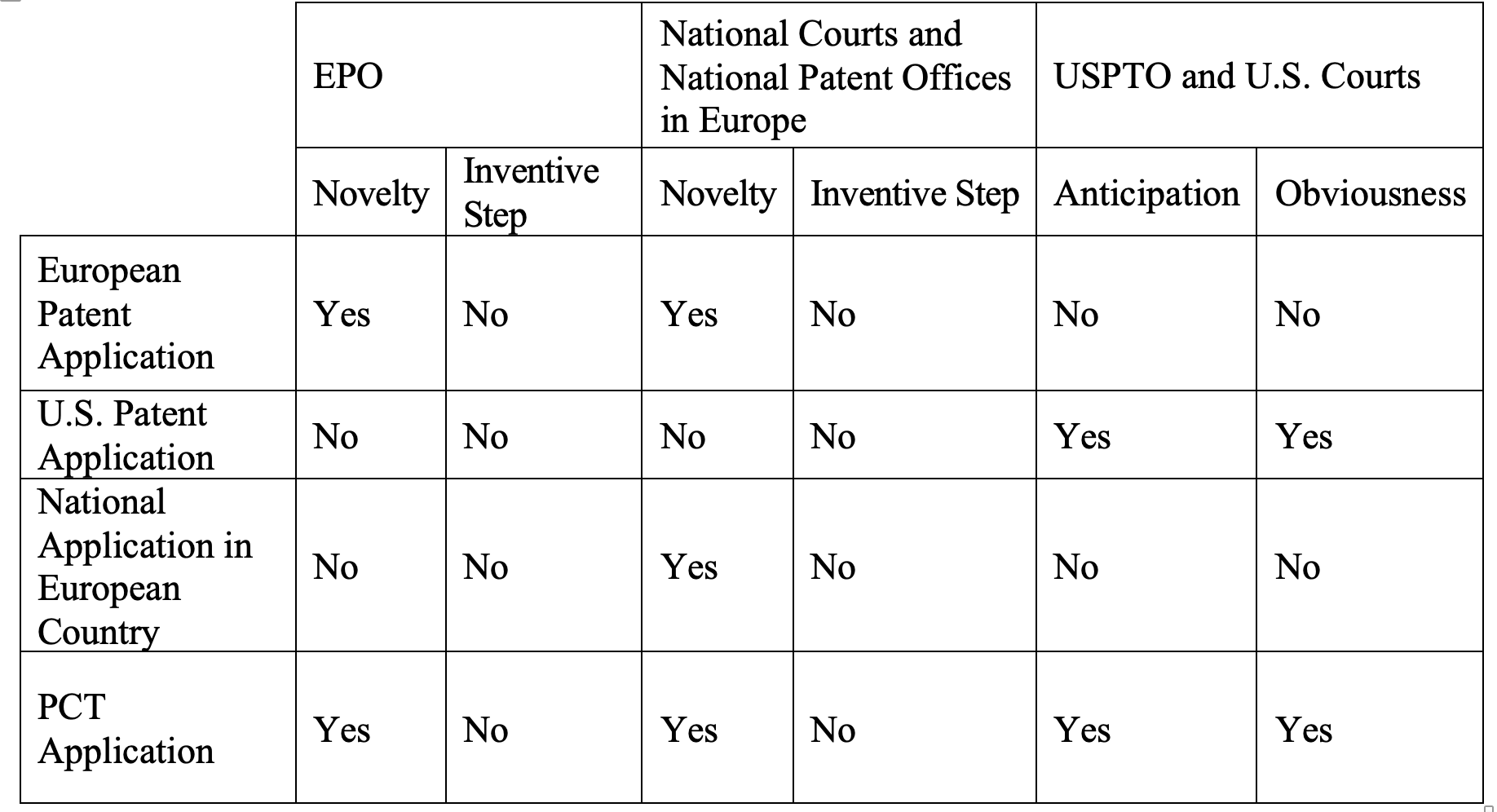

Table 1 below shows a summary of how intervening prior art can be used at the EPO, USPTO/U.S. courts, and national patent offices/courts in Europe. The left column indicates the type of intervening prior art. The top row indicates the office or court that is reviewing the intervening prior art.

Table 1: Use of Intervening Prior Art by Type and Venue

To complicate matters further, U.S. courts, the EPO, and national courts in Europe differ in how they treat PCT applications as intervening prior art. To be considered valid intervening prior art in the United States, a PCT application must designate the United States. Because all PCT applications automatically designate the United States upon filing, the PCT application becomes intervening prior art as soon as the PCT application publishes. Thus, under the America Invents Act (AIA), World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO) publications of PCT applications are treated as U.S. patent application publications for prior art purposes, regardless of the international filing date, whether they are published in English, or whether the PCT application ever enters the national stage in the United States. And, most importantly, under U.S. patent law, the PCT application can be used to judge anticipation and obviousness.

There are even more requirements than those in the US for a PCT application to be considered valid intervening prior art at the EPO. Specifically, a PCT application must have its EPO filing fee paid, the PCT application must be translated into one of the EPO languages (i.e., French, German, or English), and it must be published. With the additional requirements for intervening prior art to be considered by the EPO, applicants, litigators, and in-house attorneys should be careful when making strategic decisions (e.g., where to file, whether to start an opposition at the EPO or file an inter partes review at the USPTO) if it involves intervening prior art.

Also, each country in Europe applies different national law regarding whether the PCT application can be considered prior art, but in general this is no stricter than EPO law. Specifically, if the PCT application designates a European country, after the relevant filing fee is paid and a translation into a national language of that European country is filed, then the PCT application can also be considered intervening prior art in that country. Some countries require even less effort. However, even if the PCT application is considered intervening prior art, again, it can only be used to judge novelty and not inventive step in national courts in Europe.

These differences in the treatment of intervening prior art can impact how practitioners approach prosecution and litigation strategies in the United States and Europe in a myriad of different ways. First, the treatment impacts how companies should think about generating prior art to prevent competitors from obtaining patents. As part of a comprehensive prior art strategy, if companies want to ensure they generate prior art based on PCT applications for EPO examiners, they should first make sure they pay the European national stage entry filing fee; translate the application into French, German, or English (if necessary); and wait until the WIPO publishes the application before abandoning it. If they do not pay the filing fee, the PCT application is not considered prior art at the EPO, which means competitors can potentially enter the European market without having to address the prior art. Note also that the filing fee for a PCT application entering Europe is merely 125 EUR. Accordingly, at a minimum, any company—especially U.S. companies looking to defensively publish in Europe—should pay the European national stage entry filing fee for a PCT application.

Second, when considering attacking a competitor’s patent, companies should be careful about the differences in how prior art is used at the EPO, national courts, and the USPTO/U.S. courts. For EPO proceedings (e.g., oppositions or third-party observations), companies can cite intervening EP patent applications, but again, these applications are relevant only for judging novelty. For national court proceedings, companies can cite intervening national applications for the state but must also research on a country-level basis whether EP patent applications are citable as intervening prior art.

Third, companies should be careful when reviewing intervening prior art where the same inventor is involved for U.S. patents and where the inventor was under an obligation to assign the ownership of the invention to the same person or the same entity for the pending application. This may be natural for U.S. applicants to check, but it is not common for applicants with a European background. Specifically, even if an application qualifies as intervening prior art, one must be careful to check the inventors’ names to determine if the same inventors are involved and the one-year grace period regarding public disclosure can apply. If this grace period applies, the intervening prior art will not qualify as prior art in the United States. if the person who made the public disclosure obtained the subject matter directly or indirectly from the inventor or joint inventor (including if the inventor is the one disclosing). Further, there are also exceptions when the intervening disclosure and claimed invention are owned by the same person, but this is difficult to verify without public disclosure in the USPTO assignment database. U.S. companies may be familiar with the one-year public disclosure grace period in the United States. and what is required to assert it in court and at the USPTO; however, European companies can also consider preparing for intervening prior art in the United States (e.g., a company’s own application) by asking for an affidavit from the inventor regarding a public disclosure of the invention during the grace period or from the person responsible for the disclosure during the grace period (e.g., from a university who had permission from the inventor to publish the invention prior to the filing date of an application for the invention in the United States).

Fourth, as noted, European patent attorneys may be able to avoid Art. 54(3) EPC prior art because it is considered weak (e.g., purely for novelty purposes), but that may not be the case in the United States. For example, if a Euro-PCT application (i.e., a PCT application that enters the EP national phase) is considered Art. 54(3) EPC prior art, that same prior art in the United States can be considered for novelty and obviousness in the United States. So, the European company should not assume that prior art weaknesses in Europe translate to similar weakness in the United States.

Part II of this series will build on Part I to focus on software patents with U.S. and EP family members.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Brett

September 26, 2021 03:26 pmExtremely helpful piece for those protecting IP in multiple counties

George

September 16, 2021 12:28 amAll proof that we need a ‘universal patent system’ issuing single ‘universal patents’, valid in all countries, along with an ‘international IP court’, that can ‘quickly’ decide ALL disputes, from eligibility, to allowance, to validity, to infringement, originating in any country. The current system is no longer sustainable and has now become an economic disaster. Only attorneys could possibly think otherwise or like what we have now.

Our current system of valuing and transacting IP is simply incompatible with 21st century needs (especially the need for speed, economy and financial rewards). It now just sucks all value out of innovation, before it even has a chance to fairly and equitably be used for the benefit of all. Innovation is supposed to benefit everyone, not just a handful of powerful people or organizations. That’s obviously NOT what the Founders intended.

‘IP thievery’ is clearly NOT the same thing as innovation, yet it has now become the dominant ‘substitute’ for the real thing. We are all fooling ourselves that this can keep going on, just like we continue to fool ourselves that we can keep using fossil fuels – just because we always have. The human preference for continued denial of problems as a way to somehow ‘magically’ make them go away, will lead to very bad and likely irreversible outcomes! Once inventors are gone, they’re gone (for at least one or two generations). So, we better start ‘paying them’ again!

For some reason I’m not as worried about our lawyers, since they seem to never innovate or invent anything – especially when it comes to the practice of law! They insist on that remaining ‘exactly the same’ for the next 1000 years!

MaxDrei

September 3, 2021 02:35 pmSame as Alex, I’m looking forward to tips how to reconcile drafting best practices in two different First to File jurisdictions, the USA and the Rest of the World. Under the Paris Convention, it makes no sense to write two applications, one for the USA and a different one for the rest of the world. Or does it?

But that’s also a rather hackneyed subject by now. Personally, I’m much more intrigued with the thought of Part III, the differences across the Atlantic, when it comes to interviewing the Examiner.

MaxDrei

September 3, 2021 04:59 amI’m very impressed. Lots of sound advice in there. I particularly liked it that there is so much about competition between your patent portfolio and that of your competitor.

First to File is a very exacting environment, that puts a high premium on patent drafting skills. Watch for example, how the CRISPR-Cas9 rivals fight it out at the EPO, in inter Partes, post-issue, deep-pocket funded oppositions at the EPO, over the next ten years or so, each citing the filings of the other protagonists as prior art. Pretty sure that for each case fought over, the outcome in the USA will be different from the corresponding patent family member in Europe.

But there’s nothing new here though, is there? Ever since the AIA went through The Congress, people have been writing exactly what’s in this article, about “intervening” prior art. They failed to communicate it as clearly, however, as the writers of this article.

Alex

September 3, 2021 04:14 amGreat dive into many intricacies of the two most important patent systems. Very much needed for European practitioners (like me) often confronted with transatlantic portfolio optimization. Hoping for a sequel with more insights about drafting strategies that would be compatible with both systems.

Shyon

September 2, 2021 01:32 pmGreat article helped answer a lot of my questions, very resourceful