“In the creator economy, Professor Vasbinder suggests, it is less about enforcing the letter of the IP law, and more about receiving recognition that can be monetized.”

Millions of content creators hoping to establish a cash machine on platforms like TikTok, YouTube and Instagram are learning that it takes more than lively moves and thousands of followers to be taken seriously.

Millions of content creators hoping to establish a cash machine on platforms like TikTok, YouTube and Instagram are learning that it takes more than lively moves and thousands of followers to be taken seriously.

They are also discovering that not all creators are created equal, even when they are the source.

Content on TikTok and other social media platforms is theoretically copyrightable. In practice, however, the IP rights of social media creators today are less clear. Work generated by lesser known creators, especially if they are young and Black, is being stolen with little apparent recourse.

Black content creators went on strike against TikTok back in June because they believed some of their work was being used without being credited and that TikTok was not sufficiently policing infringers. Copyright did not appear to be the primary issue. Whether the fault lies with TikTok, society or the IP system—or a combination—is unclear. Videos and other content provided directly to social media by individuals and businesses with the potential to go viral are a powerful resource that speaks to the complexity of IP rights in a digital world.

The power of some platforms to endow creators with superhero-like powers and bestow value where there would otherwise be none, often overnight, is something IP creators and owners are just beginning to comprehend. These apps appear to be able to turn almost anyone or thing into a monetizable meme. But success is rarely that simple. The original “Renegade” dance challenge, created by Jalaiah Harmon, a 14-year-old from Atlanta, became associated with Charli D’Amelio, one of the biggest stars on TikTok. D’Amelio, with more than 125 million followers, was comfortable taking the credit and adding to her following and list of sponsors, that is until there was push-back on social media.

Coverage in The New York Times in early 2020 helped identify Harmon as the original creator of the dance and called attention to how the Atlanta teen hadn’t been given credit.

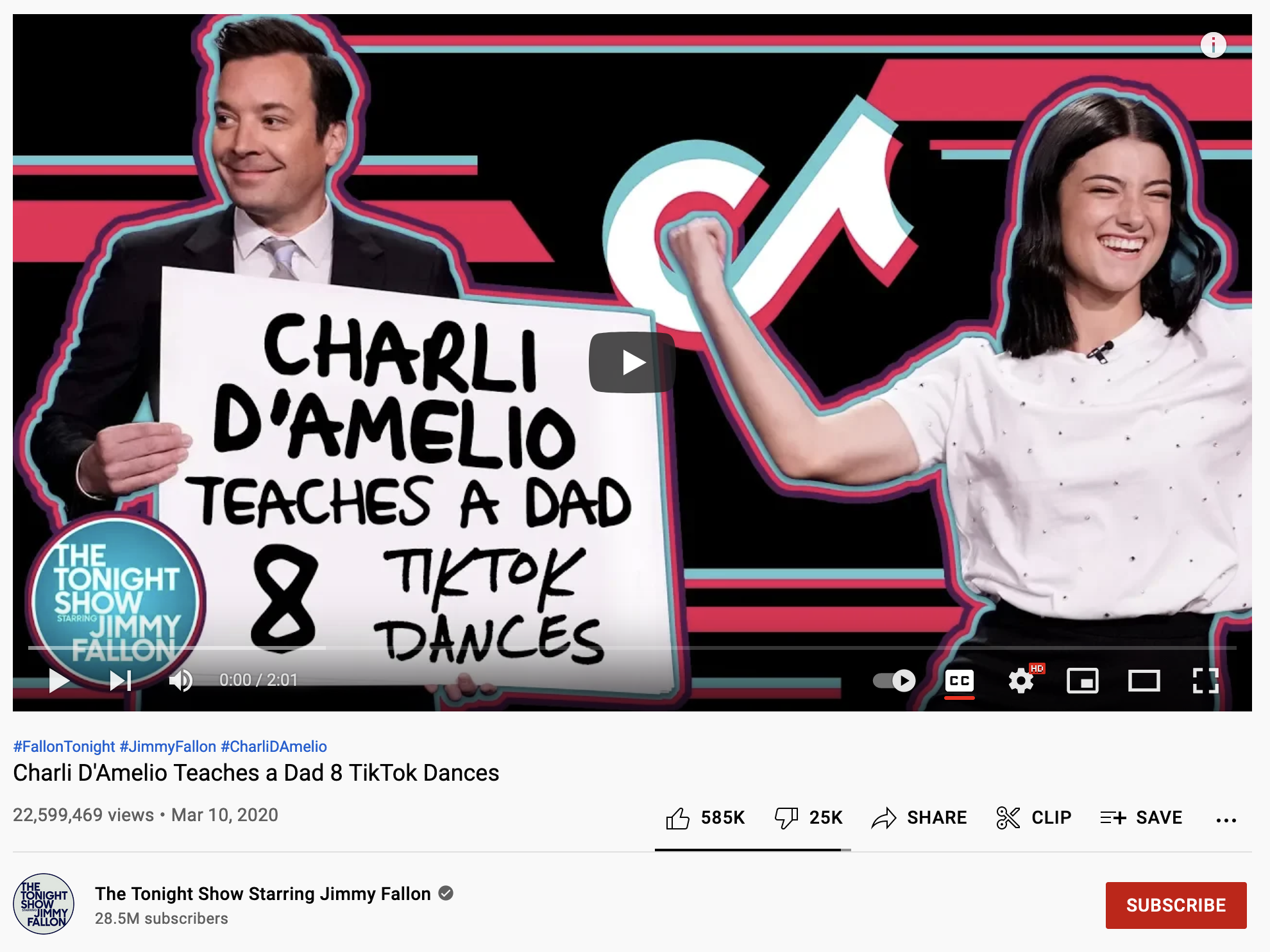

Since then, media stars such as D’Amelio and Addison Rae have added dance credits to their TikTok videos. Frustration regarding Black creators’ lack of recognition for their work were fueled earlier this year when Rae was invited to appear on The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon to perform viral TikTok dances made by several creators, most of whom were Black. After public outcry, Fallon later invited the original choreographers to appear on the show virtually.

Choreography and Copyright

Jill Vasbinder Morrison is a dancer, scholar, and community activist teaching dance studies at the University of Maryland. She supports content creators and their dance moves but does not believe that copyright enforcement is the way for them to go in an area as fast and diffuse as social media.

Tired of not receiving credit for their original work — all the while watching white influencers rewarded with millions of views performing dances they didn’t create — many Black creators on TikTok joined the widespread strike in late June, refusing to create any new dances until credit is given where it is due.

“There has to be a broader conversation about creators having equity in these start-ups,” Isaac Hayes III, the founder and CEO of Fanbase, a subscription-based social media platform told The New York Times. “Instagram and Facebook make billions. How much of that is being passed on to the creators, especially those who drive millions and millions of views?”

In Taylor Swift’s contract with her new label, Universal Music Group’s Republic Records, specifies that the equity the company owns in Spotify, worth more than $1 billion, will be distributed to fellow artists on the label when the shares are sold. This, Taylor believes, will help make up for the shortfall in their streaming income. Swift’s move, as radical as it is serious, suggests that if platforms cannot afford to pay musicians sufficiently for streams, they can by sharing a small portion of equity. Spotify’s market value is approximately $47 billion dollars.

Variety, the entertainment industry publication, is not convinced the strike will have much impact. It believes that Black creators may be cutting themselves off from greater recognition at a time when they most need it. The obstacles faced by content creators today are not unlike those of inventors, musicians and image makers of the past. Today, however, information moves faster and value is more ascendant. Cultural appropriation is something that Black musicians and dancers are all too familiar with, and something social media has only partially addressed.

“Harmon is only the latest in a long list of women and people of color whose choreography and dance work have been pilfered for profit,” says Vasbinder, “a story that dates back to the origins of jazz dance in the 19th and early 20th centuries.”

“Because Harmon didn’t get credit, she wasn’t able to reap the benefits of more views and followers, which, in turn, could have led to collaborations and sponsorships.”

In the creator economy, Professor Vasbinder suggests, it is less about enforcing the letter of the IP law, and more about receiving recognition that can be monetized. Knowing the law does not hurt. Social media has become an increasingly lucrative industry for providers (distributors) like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram, but little more than an avocation for the vast majority of creators. These and other platforms provide access—a ‘taste’ of fame—but seldom are viable income sources. Sorting out the status of IP rights on social media could help bring order to an effectively lawless and arguably exploitive industry. This is especially important to consider because a significant majority of creators have grown up in a world where social media is the norm.

The Currency of Social Media

If creators are unable to meaningfully enforce their copyrights, it may not help to cry that they are being infringed. In social media, recognition by creators with the most followers is almost as lucrative cash; multi-million views and followers, literally, can be taken to the bank. Some of the most valued assets today, followers and views – appear to escape not only the balance sheet but the IP system entirely. They suggest that the use of trademark, copyright and trade secrets is due to be modernized. Patents have already undergone a tectonic shift in licensing; content, it would seem, is close behind.

“TikTokers like Charli D’Amelio and Addison Rae Easterling — the most followed and third-most-followed creators on the app — have become popular for re-creating dances made by young Black creators,” reports Variety. “In late 2019, D’Amelio and Rae quickly shot to fame for dancing to K Camp’s “Lottery (Renegade),” sparking a viral trend on TikTok and earning the dancers millions of followers in the process.”

Creators only get paid for traffic when they hit a certain substantial level of followers and hits. For YouTube, the metric is 4,000 hours annually or 1,000 subscribers. To get to 4,000 hours, you have to generate 240,000 minutes of YouTube watch time. If you have 20,000 views per day, and your average click-through rate (the rate at which viewers who land on your site do not immediately abandon it) is 50%, then your projected yearly earnings will be $10,403 – $17,338. That a lot of work for less than $867-$1,445 per month.

It’s been estimated that you can earn 2-3 cents per 1,000 views on TikTok. Most influencers make money on TikTok by developing direct partnerships with other brands and creating branded content. Technically there is no minimum number of followers you need on TikTok to start getting paid, but the higher the following, and the higher number of views, the more revenue you are likely to generate.

$20 for 500K Views

Influencers using TikTok’s Creator’s Fund earn at a rate of 2-4 cents per 1,000 views, which means that a relatively successful video of 500,000 views would net you about $20. Prolific creators with tens of millions of followers can rake in between $100,000 to $200,000 annually from the Fund, according to the site Tube Filter. For the vast majority of influencers, however, it’s difficult to make TikTok into a full-time income based on ad revenue alone. TikTokers who have more than 100,000 followers can make from $200 to $5,000 a month. It is unclear how many are generating at the $5K level.

When creators get near the 10,000 follower mark, smaller brands might offer $100-500 to mention them in a post (this can include a “music integration,” in which a creator gets paid to play a track in the background of their video). With more followers, influencers subsequently are offered promos more consistently, allowing them to bump up their prices.

An example is provided by Business Insider of a fashion influencer with 250,000 followers who says she posts five times a week, and two or three of those posts are usually sponsored. Her rates for sponsored content are $200 for music integration and $400-$600 for product or brand integration.

Based on this, if an average week is one music integration with two brand integrations, it would be roughly $1200 a week, or $62,400 per year, before taxes (you could conceivably add a few thousand in ad revenue, too). This represents one post per day. The number of promoted posts and their fun factor can increase a content creator’s income. Rates could be quoted higher but that depends on the creator’s negotiating skills and demand from sponsors. The net-net: it is a remarkably hefty lift to go from casual creator to eking out even a basic living.

Who’s on Top?

Forbes ranks the Top Seven TikTok Earners, with Adison Rae Easterling and Charli D’Amelio at the top.

Charli D’Amelio has over 125 million followers. She exploded onto the scene with videos of dance choreography. Her “secret” TikTok account also has over 11 million followers. The 17-year-old has garnered over 9.0 million YouTube subscribers, accumulating more than 251 million views. Forbes reported her 2020 earnings at $4 million. Her 2021 reported net worth is $8 million.

What does this mean for Black and other creators who believe their content would be more valuable if it was not being stolen by celebrities? The likelihood of an audience of followers the size of Easterling or D’Amelio is incredibly rare. It may be wiser to take the substantial handful of followers a creator may have generated, say 100,000 or even 50,000, and establish a monetizable presence. It is very hard to go head-to-head on social media in a pure numbers game. If success cannot be facilitated by copyright it can at least be facilitated by source credit or endorsement.

Using TikTok content without credit may be theft even if it is not copyright infringement. It is certainly unethical. Hiring a lawyer to go after infringers may be a zero-sum game with which most photographers and many song writers are well acquainted. The answer may be to use source credit to build on. Without source credit there is only copyright strategy, and currently many content providers do not believe that amounts to very much.

Takeaway on Takedowns

YouTube has been inconsistent on takedowns and TikTok is even worse. Content creators cannot look to them to enforce their rights. What they can do is make sure that everyone who should be credited is, by setting a standard of how that should work. Whether it be dance moves, songs, or images, it hurts creators to have their work ignored; it is worse to have it stolen. The ultimate affront is to have it used, consciously or not, by someone else without acknowledging the source.

Content creators should not wait for YouTube or TikTok to police their rights. Leadership in content abuse standards among social media creators can come from the creators themselves. It’s easy to want to be a social media celeb like D’Amelio or Rae but generating cash on social media requires a special savvy—and luck. Social media is no fairer than life. The question is what can be done about content theft and does anyone outside of the victims care?

Beyonce has shown an uncommon respect for the work of other artists, many of whom she could easily pay to fade into the background and take the credit fully and fairly in the eyes of the law. Her Lemonade album, with over 100 listed contributors, is an object lesson in collaboration. She credits them all and pays them because her ego is strong enough (and capital abundant enough) to work with talented people on her own original work. The singer-songwriter, a la Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, may not fade into obscurity, but having something to say need not be an exercise in solemnity – or copyright infringement.

While the social media terrain may currently look like the Wild West, where only the biggest and baddest survive, it can be tamed if creators and viewers agree that good behavior is as important as strong rights. Social media does not have to have the final word on who gets paid and how.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

7 comments so far.

nigel worth

October 22, 2021 09:24 amSee the mischief.

I have sympathy with content creators.The solutions to avoid disposession of recognisable IP rights I agree should follow the music industry platforms, where the threat of lost revenues in musical copyrights was averted and as we know turned to hugely profitable advantage, as the cited artist Taylor Swift might testify, they have in fact increased revenues hugely.

Performing rights standards as the industry has adapted to downloads seems to be the way, with if needs be underpinnings of a revised licensing model that releases control of copyrights, formats and in some cases even associated designs tailored to this work.

For the public spirited of course Creative Commons have now evolved in most effective ways to achieve controlled release where academic or public benefit content may be released on a philanthropic but attributed basis and have additional facility for economic reward too depending on the chosen model.

In my view time to offer a sector specific licensing programme that enables Tik Tok et al to account fully for the benefits derived.

It is concerning especially that black artists seem to be at greater peril, just when they are finding their feet in the IP world and time for assurance things can be changed.

Primary Examiner

October 20, 2021 02:43 pmMr. Berman, thank you for the virtue signaling.

?_?

Anon

October 20, 2021 09:13 amENOUGH with the Fn virtue signaling please.

“Content on TikTok and other social media platforms is theoretically copyrightable. In practice, however, the IP rights of social media creators today are less clear. Work generated by lesser known creators, especially if they are young and Black, is being stolen with little apparent recourse.”

Sorry but no – the mechanism of lost rights when one (anyone) uses someone else’s social platform is the same regardless of any ISM.