“As was the case with prior 3GPP generations, 5G represents a true step forward; it promises to underly and otherwise enable an incredible amount of economic activity. Under these circumstances, patent suits are likely.”

5G—the next generation of telecommunications standards provided by the Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP)—began implementation in 2019. It boasts significant technical benefits over prior generations, including higher speeds, greater bandwidth, lower latency, and larger coverage areas. Unlike previous 3GPP standards, 5G is not limited to cellular phones. Rather, 5G will support a plethora of technologies ranging from Enhanced Mobile Broadband to Massive Internet of Things. Accordingly, 5G will support a tremendous amount of economic activity: by 2026, 5G will have 3.5 billion subscribers and will account for 84% of mobile subscriptions in the United States. By 2035, 5G is expected to underly $13.1 trillion in global economic activity, accounting for 0.2% of the 2.7% projected annual global GDP growth.

5G—the next generation of telecommunications standards provided by the Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP)—began implementation in 2019. It boasts significant technical benefits over prior generations, including higher speeds, greater bandwidth, lower latency, and larger coverage areas. Unlike previous 3GPP standards, 5G is not limited to cellular phones. Rather, 5G will support a plethora of technologies ranging from Enhanced Mobile Broadband to Massive Internet of Things. Accordingly, 5G will support a tremendous amount of economic activity: by 2026, 5G will have 3.5 billion subscribers and will account for 84% of mobile subscriptions in the United States. By 2035, 5G is expected to underly $13.1 trillion in global economic activity, accounting for 0.2% of the 2.7% projected annual global GDP growth.

Where money and technology meet, patent litigation follows. It was just a short time ago—in the mid-2000s—that Apple, Google, Samsung, and others made major patent acquisitions, proceeding to assert them against one another to gain an edge in the 3G smartphone space. In addition to these suits, many others were brought by Patent Assertion Entities (PAE), small companies often created specifically to acquire, maintain, and assert patents against large industry players. We are already seeing the next generation of 5G litigation proceed across the world: one of the first 5G PAE suits was filed in August in the Eastern District of Texas, and, just a few weeks later, Nokia was sued in both China and Europe for infringement of 5G patents. And this is only the beginning.

In light of the rising wave of 5G litigation, this article examines three core preconceived notions regarding standard essential patent (SEP) litigation. As is the case with most preconceived notions, these are no longer properly informed. First, this article discusses what actually makes a patent standard essential and whether all declared SEPs truly are essential to practicing a given standard. Second, the article discusses how proving infringement of an SEP differs from the case of an ordinary patent. Finally, the article discusses the viability of injunctions as a remedy in SEP infringement cases.

What Makes A Patent Essential?

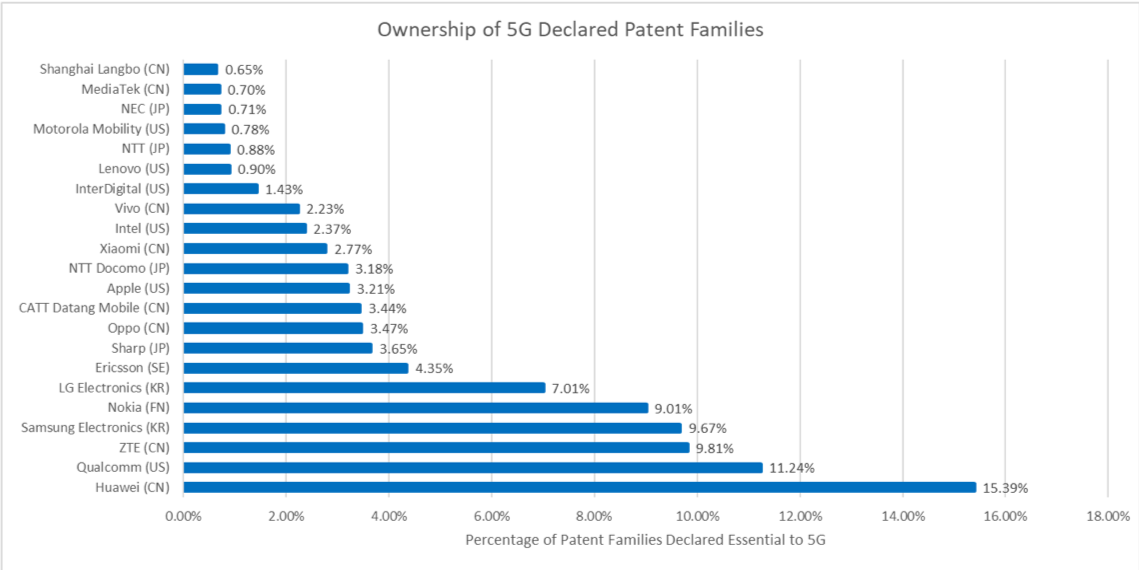

5G is not just a technology, it is a standard. As such, 5G incorporates thousands of technologies described in tens of thousands of patents. Whether these patents are essential to practicing 5G ultimately depends on what the 3GPP participants determine to be the final implementation of the standard. 3GPP asks all participants and other relevant stakeholders to disclose relevant patents that the company owns, is prosecuting, or is otherwise aware of, declaring these patents “standard essential.” As can be seen from the chart below, just 22 companies—spread across the world—account for the vast majority (97%) of 5G patent declarations.

The disclosure policy is an important one. When a company declares a patent or pending application essential, 3GPP also requests that it commit to license the patent on Fair, Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms. Of course, the company may choose not to license its intellectual property on FRAND terms, but in such cases, 3GPP will likely choose to adopt a different technology into the standard. FRAND terms were created to prevent patent holdup: a patent holder extracting supracompetitive value for an asserted patent based on the fact that the industry has become “locked-in” to the standard that the patent allegedly covers. In this case, the patent holder extracts value based on the standard and on the concomitant transaction costs that would be associated with designing around the asserted patent. These patents would thus “hold up” progress. Thus, to allay these fears, 3GPP requests that patentees who declare their patents essential license them on FRAND terms.

Notably, however, 3GPP takes no position as to whether a patent declared essential to a standard is in fact essential to practicing that standard. In short, it is patent owners—not the standard setting body—that declare a patent essential. As a consequence, the vast majority of patents declared essential to a standard are not. Experts estimate that only 10-47% of declared patents to the 2G/3G/4G standards are actually essential to practicing the standard and thus up to 90% of patents declared essential to these standards are not, in fact, essential. As much of the 2G, 3G, and 4G standards have been incorporated into 5G, we can expect to see similar rates of over declaration for 5G as well.

How is Infringement of an SEP Proven?

SEP holders can often fast track infringement proofs. Whereas infringement is normally shown “by comparing the claims to the accused products,” Godo Kaisha IP Bridge 1 v. TCL Commc’n Tech. Holdings Ltd., 967 F.3d 1380, 1384 (Fed. Cir. 2020), SEPs offer a shortcut. Under the right circumstances, an SEP patentee may instead rely on an accused product’s compliance with a standard to prove infringement and, in fact, can rest on this alone. What is most important to this inquiry is how the patent reads on the standard and how the accused product implements it. There are three real scenarios of interest: (1) where the patent reads on a mandatory implementation of the standard; (2) where the patent reads on an optional implementation of the standard; and (3) where the patent does not read on the standard at all.

In the first scenario, i.e., “where, but only where, a patent covers mandatory aspects of a standard, is it enough to prove infringement by showing standard compliance” alone. Id. (emphasis added). The reason for this, as the Federal Circuit notes, is efficiency. If the patent covers a mandatory implementation of the standard and the accused product admittedly practices the standard, “it would be a waste of judicial resources to separately analyze every accused product that undisputedly practices the standard.” Fujitsu Ltd. v. Netgear Inc., 620 F.3d 1321, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2010). Determining whether the SEP is truly essential is a fact issue for the jury. Godo, 967 F.3d at 1385. It also bears mentioning that some district courts may sidestep this holding at least slightly, requiring more disclosure than simply determining the asserted patent reads on a mandatory portion of the standard in such a way that it cannot be designed around. This is often done in reference to local rules which may be inconsistent with the holdings in Godo and Fujitsu. See, e.g., Rambus Inc. v. NVIDIA Corp., No. C-08-03343 SI, 2011 WL 11746749, at *9 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 24, 2011) (relying on a narrow read of Fujitsu as well as local rules to compel plaintiffs to provide additional detail in their infringement disclosures).

The second scenario occurs where certain patents may not be essential to practice the standard as a whole but may instead be essential to one or more optional implementations of the standard. For example, a patent may be essential to implementing aspects of the 5G standard related to the Internet of Things but may be irrelevant to implementing other aspects of the standard, such as Vehicle to Everything (V2X) communications. These patents are not full SEPs, but the Federal Circuit has still recognized its shortcut for proving infringement. Under these circumstances, a patentee may show infringement by proving that the patent reads on the same optional implementation of the standard that the accused product practices. Godo, 967 F.3d at 1384. Determining whether a patent fits this category is also a fact issue for the jury. See id. at 1385.

In the final scenario, i.e., where the patent does not even cover an optional implementation of the standard, the patentee can rely on no shortcuts. Instead, infringement must be shown using the conventional approach, “by comparing the claims to the accused products.” See id. at 1384–85. This type of patent is not an SEP, regardless of whether it has been declared as such. Infringement must also be shown using the conventional approach where standards are not written with sufficient detail or specificity to allow for a finding of infringement on that disclosure alone. Fujitsu Ltd., 620 F.3d at 1327–28.

Despite these shortcuts, plaintiffs asserting SEPs surprisingly do not win on infringement claims significantly more often than those asserting any other type of patent. Rather, courts find infringement (and validity) of SEPs at much the same rate they find infringement of other types of patents. This is also true for PAEs, which win at significantly lower rates than practicing entities, even when asserting SEPs.

Are Injunctions Available for SEP Infringement?

For years, policymakers have largely counseled against the availability of injunctions, especially for infringement of an SEP. In 2006, the Supreme Court limited the availability of patent-based injunctions in district courts in eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C. 547 U.S. 388, 391–94 (2006). Then, in 2013, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) and Department of Justice (“DOJ”) issued a joint policy statement “recommend[ing] caution in granting injunctions or exclusion orders based on infringement of voluntarily F/RAND-encumbered patents essential to a standard,” finding that “[i]n some circumstances, the remedy of an injunction or exclusion order may be inconsistent with the public interest” because the patent was pledged to be FRAND-licensed.

In part relying on the joint position of the USPTO and DOJ, the United States Trade Representative rejected an exclusion order Samsung had won from the United States International Trade Commission (“ITC”) on August 3, 2013. The USTR veto seemed to shift ITC jurisprudence, threatening the possibility of receiving an exclusion order when asserting an SEP. This trend was recognized in a subsequent letter from the DOJ in 2015, noting that “[o]ver the past several years, U.S. patent courts have recognized this principle, making it unlikely that a patent holder bound by a [F]RAND commitment, even one that does not address explicitly the availability of injunctive relief, can secure an injunction (in addition to monetary damages) in an infringement action.”

But in recent years, the paradigm has started to shift back in favor of SEP patent holders, with the ITC poised to again be a central stage for SEP disputes. In 2019, the DOJ, USPTO, and National Institute of Standards and Technology (“NIST”) issued a new statement, revoking the 2013 statement and revising their position barring injunctions to the following:

[C]ourts—and other relevant neutral decision makers—should continue to determine remedies for infringement of standards-essential patents subject to F/RAND licensing commitments pursuant to the general laws. A balanced, fact-based analysis, taking into account all available remedies, will facilitate, and help to preserve competition and incentives for innovation and for continued participation in voluntary, consensus-based, standards-setting activity.

The DOJ in 2020 also reversed its 2015 letter, noting that “concerns over hold-up as a real-world competition problem have largely dissipated.” The DOJ went on to articulate a new position far more favorable to injunctive relief:

Injunctive relief is a critical enforcement mechanism and bargaining tool—subject to traditional principles of equity—that may allow a patent holder (including an essential patent holder) to obtain appropriate value for its invention when a licensee is unwilling to negotiate reasonable terms. Denying essential patent holders access to injunctive relief has the potential to lessen returns for investors and thereby to harm incentives for future innovation.

Commenters have recognized these changes in policy will likely make SEP-based injunctions and exclusion orders more palatable. More broadly, injunctions may have been more palatable than believed all along. Recently, patent scholars have engaged in empirical research to determine the true impact of the Supreme Court’s decision in eBay v. MercExchange, which many practitioners thought significantly limited the viability of permanent injunctions in district court. They found permanent injunctions are granted in nearly three quarters of patent cases where they are sought, only slightly less frequently than before the decision. Thus, injunctions (and exclusion orders) should be viewed with renewed optimism.

Stay Tuned

Of course, uncertainty remains as the situation continues to develop. The 2020 DOJ letter has been reclassified to a lesser stature on the DOJ’s website, and President Biden has recently asked the Attorney General and the Secretary of Commerce to review the 2019 joint statement of the DOJ and USPTO, and NIST. This review is currently in process, so in the words of Jeffrey Wilder, Director of Enforcement of the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, “stay tuned.”

As was the case with prior 3GPP generations, 5G represents a true step forward; it promises to underly and otherwise enable an incredible amount of economic activity. Under these circumstances, patent suits are likely. Accordingly, the authors have examined three preconceived notions likely to influence future litigation over 5G patents including: (1) whether a “standard essential patent” is indeed essential; (2) whether standard infringement poofs apply to alleged SEPs; and (3) whether injunctions are once more a viable remedy. In each case, these preconceived notions are no longer properly informed—just like the standards themselves, litigation over SEPs is both nuanced and changing. Stay tuned.

Tune in to IPWatchdog’s Patent Masters virtual symposium, Standard Essential Patents 2021, November 8-11 for more on SEPs.

Image Source: Deposit PHotos

Image ID:188095512

Copyright:sdecoret

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

concerned

October 26, 2021 07:28 amThe big three: AT&T, Verizon and T Mobile stocks are all down 10% or more this year when the S&P 500 is up approximately 20%. And AT&T and Verizon have been dumping non-core assets to focus on the 5G build out. Apparently Wall Street does not buy this 5G promise.

I been in discussions with friends lately regarding the big three are not investing billions in 5G just to take a beat down in the stock market. They will get a payback for this 5G investment and these stocks look incredibly cheap. AT&T stock hit an 11 year low last week. This is not the Randall Stevenson AT&T of the past, the current CEO immediately reversed all the past moves. Sure the current CEO was there during blunderville, however, was he just going along with Randall Stevenson to avoid getting the ax to live for today?

This is a patent website, not a stock market forum. Big tech allegedly runs all over patent rights. Will these big 5G players be extended the same non-infringement patent courtesy from the courts and USPTO as the other big tech companies? Will evidence be tossed or not recognized? Will more undefined words be added to s101 from the bench to assist the taking of patent rights?

People who made money from big tech ridicule this website for standing up for inventors suggesting we are fools for not taking the easy “steal the invention” candy on big tech stocks.

Patent Wars or Patents destroyed?

Stephen Potter

October 26, 2021 07:25 amIt would be nice to have a similar article on the situation with respect to SEP’s in the German and Chinese courts and one on anti- and anti-anti suits…