“The fair-use defense has traditionally been viewed as a fact-bound issue. However, the opinions in Cariou and Warhol reflect a trend to determine fair use as a matter of law.”

“Fair Use” is a flexible defense to claims of copyright infringement. It is a doctrine that evolves as technology and the way in which people use copyrighted works advance. As an exception to the general law prohibiting copying others’ works, it permits copying for a limited and “transformative” purpose, such as commentary, criticism, teaching, news reporting, scholarship, or research.

“Fair Use” is a flexible defense to claims of copyright infringement. It is a doctrine that evolves as technology and the way in which people use copyrighted works advance. As an exception to the general law prohibiting copying others’ works, it permits copying for a limited and “transformative” purpose, such as commentary, criticism, teaching, news reporting, scholarship, or research.

Naturally, the way courts analyze the “fair use” defense must adapt as technology advances and the way in which creative content is developed evolves. Earlier this year, for example, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on a landmark fair use case involving the “copying” of an Application Programming Interface (API). In Google, LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., the Court held that Google did not commit copyright infringement when it used key aspects of Oracle’s programming code in the Android operating system. Using Oracle’s programming language as a building block constituted a legitimate “fair use” because Google used “only what was needed to allow users to put their accrued talents to work in a new and transformative program.” While much has been written on Google v. Oracle, we believe that a deeper understanding of that case—and modern trends in fair use more broadly—can be found in precedents arising from the world of high art.

Recent Evolution of the Fair Use Defense

Specifically, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit helped define the scope of fair use in the context of creating art using others’ photographs in two separate decisions: Cariou v. Prince and Andy Warhol Found. For Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. One might analogize the use of photographs as a building block for art with the use of the programming language in Google v. Oracle and many other contexts in which the fair use defense is often raised.

In Cariou, photographer Patrick Cariou published a book of his photographs of Rastafarian men in Jamaica. A few years later, artist Richard Prince altered and incorporated several of Cariou’s photographs in a series of paintings and collages, in a work titled “Canal Zone.” Cariou sued Prince, alleging that Canal Zone infringed Cariou’s photographs. Prince raised the defense of fair use.

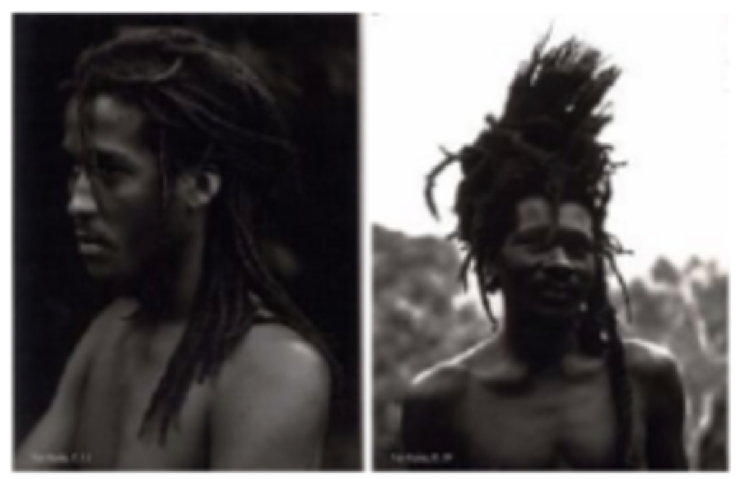

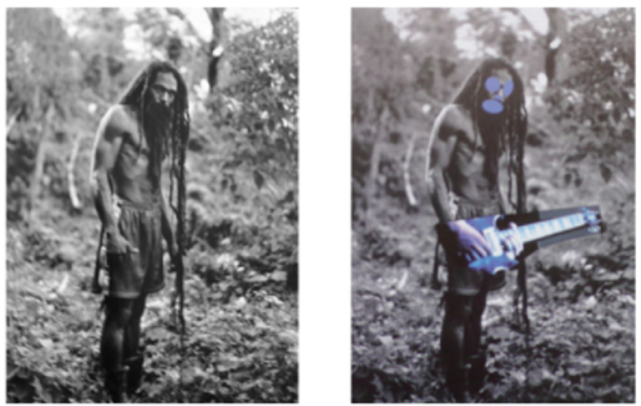

The district court found in favor of Cariou, concluding that none of Prince’s works constituted fair use, relying heavily on Prince’s deposition testimony that he was not trying to create a new meaning or message, and concluding that Prince failed to show his work was transformative in the sense of creating new meaning. But on appeal, the Second Circuit reversed, finding that 25 of Prince’s 30 works that used Cariou’s photographs were fair use as a matter of law because they were transformative. For context, the Second Circuit found that Prince’s use of Cariou’s photographs on the top line below to create the new work directly below it was transformative as a matter of law:

However, Prince’s use of the following photo on the left to create the work on the right was not found to be transformative, therefore, it did not constitute fair use:

The Second Circuit stated that, generally, the new work must alter the original with “new expression, meaning, or message” in order to qualify as fair use. However, the court did not treat Prince’s testimony regarding lack of any new meaning of his works as dispositive; rather, it stated that there is no rule requiring a defendant to explain and defend his or her use as transformative. A reviewing court should instead consider how the work appears to the reasonable observer. Similar to use of the API in Google v. Oracle, the court explained that Prince used Cariou’s photos “as raw material, transformed in the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understanding,” even though Prince did not directly comment on Cariou’s photographs. Ultimately, the court rejected the notion that to be entitled to a copyright “fair use” defense, an allegedly infringing work must comment on, relate to the historical context of, or critically refer back to the copyrighted work.

Limiting Principles

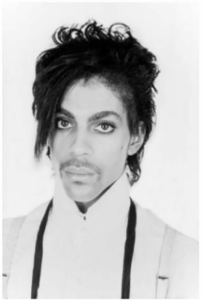

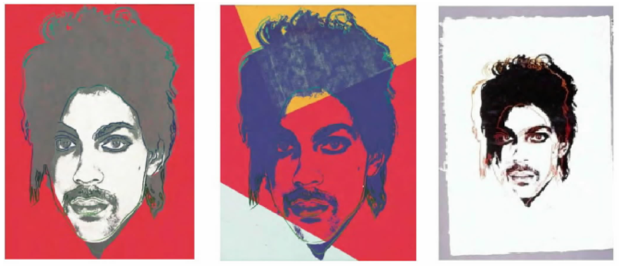

Before getting carried away with the implications of Cariou, the Second Circuit provided important limiting principles in the recent Warhol decision. There, the court was presented with a similar question as to whether an artist’s use of pre-existing photographs in a new work constituted fair use. The artist Andy Warhol created 15 works (the “Prince Series”) using a photograph of pop-icon Prince taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. For reference, the original photograph is below on the left, and the three right-most images are a few of the works Warhol created by using the photograph:

In 2016, after Prince’s death, Vanity Fair licensed some of Prince Series from the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) to use in a tribute to Prince. Afterwards, Goldsmith alleged that the Prince Series infringed Goldsmith’s photographs. AWF sued Goldsmith’s photo agency for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement or, in the alternative, fair use.

Relying on Cariou, the district court held that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph was transformative and therefore constituted fair use. The district court concluded that Warhol’s alterations “result[ed] in an aesthetic and character different from the original,” and added “something new to the world of art and the public would be deprived of this contribution if the works could not be distributed.” On appeal to it, the Second Circuit reversed, holding that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph did not qualify as fair use as a matter of law and that the Prince Series infringed the photograph as a matter of law.

The Second Circuit drew a distinction between a derivative work that adds a new aesthetic or new expression and a secondary work that goes beyond that, to a level that would be considered “transformative.” The district court incorrectly interpreted Cariou as establishing a broad rule that a secondary work was transformative as a matter of law when it adds a new expression or aesthetic to the original work. However, it was not enough that the Prince Series “display the distinct aesthetic sensibility that many would immediately associate with Warhol’s signature style.” Ultimately, the court found that the Prince Series “retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements.” Goldsmith’s photo “remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built.” To explain the result, the court used the example of adapting a play into a movie, explaining that such a movie is a “paradigmatically derivative work,” even if it might reflect a director’s signature style.

Reading these two decisions together, the Second Circuit even acknowledged that it has given some “conflicting guidance” in cases assessing the transformative nature of works. But the key is found in the analogy to Google v. Oracle by considering whether programming language, photographs, or other creative works have been used as building blocks for a truly new (and hence, “transformed”) work. Merely imprinting one’s own style on another’s work without comment or critique is derivation, not transformation. Of course, it is always most helpful to look at the actual photographs and secondary works in question (above) to help visually understand what degree of “change” may constitute transformation of an original work.

A New Trend

Finally, the fair-use defense has traditionally been viewed as a fact-bound issue. However, the opinions in Cariou and Warhol reflect a trend to determine fair use as a matter of law. Lower courts have certainly taken note. For example, the fair use defense in Hosseinzadeh v. Klein was adjudicated by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on a motion for summary judgment. Plaintiff Matt Hosseinzadeh posted a video skit on YouTube featuring his “Bold Guy” character, in his “Bold Guy vs. Parkour Girl” video. Ethan and Hila Klein created a “reaction video” to Hosseinzadeh’s video, which they also posted on YouTube. Hosseinzadeh’s video is five minutes and twenty-four seconds, and the Kleins used three minutes and fifteen seconds of it to create their 14-minute-long video. The court found that the defendants’ use was fair as a matter of law, noting that the purpose of the work weighed heavily in their favor because their video was “quintessential criticism and comment.”

Given these emerging trends in the law, it is important for defense counsel to identify and pursue potential fair-use defenses early in a copyright litigation, even outside the traditional areas of commentary, criticism, teaching, news reporting, scholarship, and research.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:63109787

Copyright:Rawpixel

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

5 comments so far.

Anon

November 17, 2021 09:55 amTwo cases seven years apart do not as a matter of logic determine a trend.

At that point, I could not reach where the authors wanted to go.