Towards the end of 2019, I was finishing a book, AI Concepts for Business Applications. The last chapter was titled, “The Future.” I wrote about quantum computing and a version of deep learning that was related: a “quantum walk neural network.”

Towards the end of 2019, I was finishing a book, AI Concepts for Business Applications. The last chapter was titled, “The Future.” I wrote about quantum computing and a version of deep learning that was related: a “quantum walk neural network.”

In 1980, the idea of a quantum processing unit was proposed. Such a processing unit doesn’t use the 1s and 0s with which we’re familiar. That “classical” way of thinking is the way we think, with a 1 for true and a 0 for false, and combinations—for example, a “false positive.” Quantum computing is based on a “superposition” of states called “quantum bits” or “qubits” for short. But there’s a big difference between the way we think and the way nature behaves.

In 1981, the late Caltech professor, Richard Feynman (a Nobel Prize co-winner for his work with “quantum electrodynamics”) summed it up: “Nature isn’t classical, dammit, and if you want to make a simulation of nature, you’d better make it quantum mechanical, and by golly it’s a wonderful problem, because it doesn’t look so easy.”

Now, quantum computing is beginning to emerge. It started with hardware:

- In March of 2017, IBM announced an open Application Programming Interface (API) called IBM Q, where Q means quantum.

- In December of 2017, not to be outdone, Microsoft announced a preview version of a developer kit with a programming language called Q#.

- In January of 2018, the world of neural networks, which includes a convolutional neural network (CNN), primarily for images, and a recurrent neural network (RNN), primarily for text, expanded to include a Quantum Walk Neural Network (QWNN). The QWNN paper is entitled “Quantum Walk Inspired Neural Networks for Graph-Structured Data” was written by Stefan Dernbach (then a PhD student at the University of Massachusetts College of Information and Computer Sciences); Arman Mohseni-Kabir (then a graduate student in physics at UMass Amherst); Don Towsley (Dernbach’s PhD advisor); and Siddarth Pal (a scientist with BBN Raytheon Technologies).

In their Abstract, they wrote, “A QWNN learns a quantum walk on a graph to construct a diffusion operator which can be applied to a signal on a graph. We demonstrate the use of the network for prediction tasks for graph structured signals.”

Note the phrase “prediction tasks.” That’s what deep learning known for being able to do, that is, once trained with labeled data, a model “for the label” (or category or classification) is able to identify images or text from a blizzard of input the model’s never seen before, and yet find the needles that match to the model. Such models have become known as “prediction machines.”

- In March of 2018, Google’s Quantum AI Lab announced a 72-qubit processor called Bristlecone.

- On July 19, 2018, Google announced an open-source framework called Cirq (where the C is short for cryogenic) and plans for a Bristlecone cloud.

- On January 8, 2019, IBM announced IBM Q System One as the first integrated quantum system for commercial use.

- On February 21, 2019, Google announced a cryogenic controller that used only two milliwatts of power.

- In May 2019, Microsoft announced that, in the summer of 2019, it would open-source parts of its Quantum Developer Kit on GitHub, including the Q# compiler and quantum simulators.

- On October 23, 2019, in a Nature paper, Google announced “quantum supremacy.” The paper was entitled, “Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor.” As Google summarized the advance in the Abstract:

A fundamental challenge is to build a high-fidelity processor capable of running quantum algorithms in an exponentially large computational space. Here we report the use of a processor with programmable superconducting qubits2,3,4,5,6,7 to create quantum states on 53 qubits, corresponding to a computational state-space of dimension 253 (about 1016). Measurements from repeated experiments sample the resulting probability distribution, which we verify using classical simulations. Our Sycamore processor takes about 200 seconds to sample one instance of a quantum circuit a million times—our benchmarks currently indicate that the equivalent task for a state-of-the-art classical supercomputer would take approximately 10,000 years.” (Boldface added.)

From this much, you may gather that the field of quantum computing had finally made it to the launch pad of an “emerging technology.”

Quantum Computing Patents

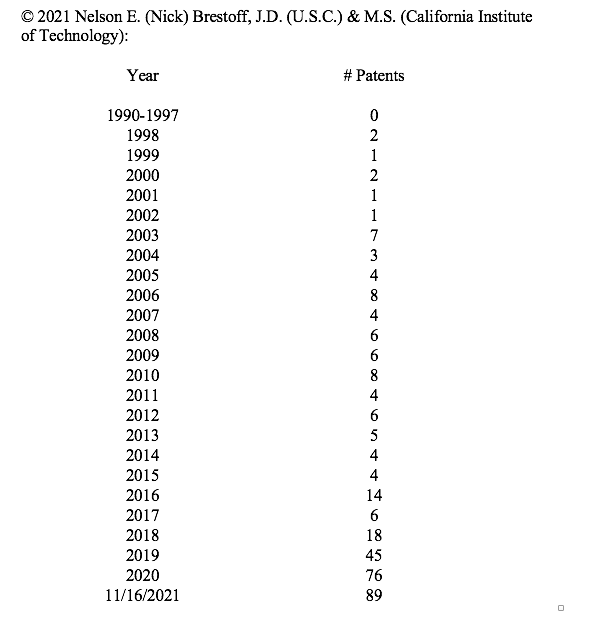

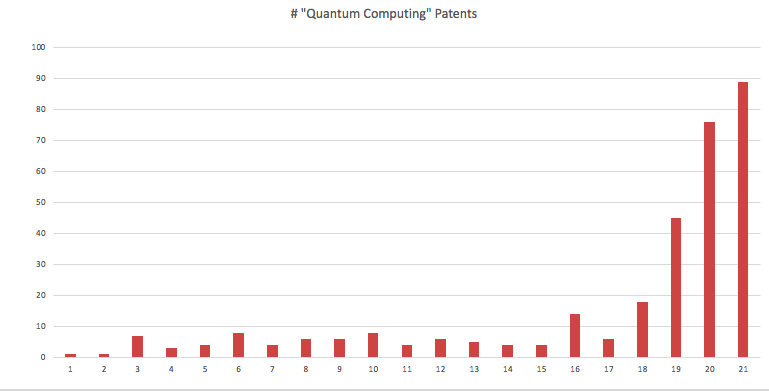

With that history, let’s switch to patents. I’ve previously presented bar graphs for two emerging technologies: deep learning and blockchain. These graphs are based entirely on searching the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s (USPTO’s) patent database.

As before, I searched for a key word or phrase in the Claims field of the USPTO database. For the annual data, I searched the USPTO for “quantum computing” in the Claims and for the Issue Date on an annual basis. The bar graph for “quantum computing” is surprisingly similar to the bar graphs for deep learning and blockchain.

THE QUANTUM COMPUTING PATENT LAND RUSH

The total on November 16, 2021 was 322. Keep in mind that the 2021 total is for a partial year as of November 16. Since there are six more Tuesdays in 2021 (when new patents are announced), I’ll predict a year-end for 2021 of 150 or more.

If you compare this bar graph to the graphs for deep learning and blockchain, the conclusion is readily apparent. We are living in a time when deep learning, blockchain and quantum computing are rapidly emerging, and almost simultaneously. Wonders we cannot now foresee will come from these advances.

If readers know of yet another candidate for an emerging technology, please let me know in the comments below.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

18 comments so far.

Nick Brestoff

November 24, 2021 10:28 amTo Anon and Step Back, with an apology to Step Back and thanks to Anon, I stand corrected. My reflexes were Drax-fast which, in this case, was too fast. 😉

Anon

November 24, 2021 09:44 amNick,

Shall I call you Drax?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iLttd33j-GQ

By the way, that was step back that added the honors of “stripping down” the term computer — which augments the irony of the point – and makes your Drax leap all the more ‘impressive.’

Nick Brestoff

November 23, 2021 10:45 amTo Mark G. I tried the original links and they opened for me this time. Lens.org is patents on a global scale, and is NEW to me. The USPTO patent database is focused only on the US, and I agree that a global way of sharing science and technology innovations are a better way to go, especially as to climate change. I’ve now found the Monticello Group Ltd. in Medina WA, which is physically near me (Sequim, WA) and so I’ll be spending time to learn more about Lens.org and will perhaps contact the Monticello Group. Thanks very much!

Anon

November 23, 2021 10:40 amThank you step back – your post well-augments the aim of my point of irony.

Nick Brestoff

November 23, 2021 10:23 amTo Anon: I only provided a way for you to inquire about how others may have defined “generic computer.” The way you’ve stripped down a “computer,” my inquiring mind settled on an abacus.

Primary Examiner

November 23, 2021 09:52 amThanks for another really good article.

Another candidate for an emerging technology could be edge computing.

step back

November 23, 2021 02:16 amAnon @6

I do not believe there is a definitive description of “computer” let alone the “generic” kind.

For example, must a “computer” have a graphical display? Or even an interface for driving such a display/monitor?

Must a “computer” have a keyboard and/or mouse-like input device? Or even an interface for driving such a user input device?

Must a “computer” have a nonvolatile data read/write storage device (a hard drive)? Or even an interface for driving such a data storage device?

Must “generic” computers come equipped with the displays, (and/or speakers) and input devices and nonvolatile data storage devices?

When does a computer become a “programmed” computer? (Consider that most microprocessors are programmed at the micro-code level.)

Inquiring minds don’t want to know.

Mark G

November 22, 2021 07:47 pmThanks Nick, sorry those results didn’t load for you.

An alternative to the keyword analysis you used is using the classification codes (or a combination). CPC G06N10/00 and B82Y10/00 represent most of the 2600 patents that show up using keywords. A visualization of the CPC codes identified through the keyword search is available here: https://link.lens.org/kTdxKmQLLHi

The IonQ patents show up in G06N10/00 visible here: https://link.lens.org/Ls1Bq8Ra7ff

The IonQ work with Univ Maryland and Duke is also visible in that analysis.

Pro Say

November 22, 2021 04:57 pmThanks Nick.

Anon

November 22, 2021 04:01 pmThanks Nick,

My comment in reply was more tongue in cheek than asking for any indicator as to how individuals may have decided to use the term.

This is due to the fact that the term is a legal term of art WITHOUT having a specific and exacting physical structure (as in, those who often use the term without thinking, WANT exacting physical structure in claims — picture claims — when such is neither necessary nor desirable).

It is a point of irony that was being made.

Nick Brestoff

November 22, 2021 03:56 pm1. To Mark G: I opened the links and was able to see your (broader) search for “quantum computing” in the title or abstract or claim, but not any of the results.

2. To Max Drei (and other readers): In the USPTO’s lingo, ACLM is the code for “claims,” AN is the code for Assignee. When using ACLM, a multiple word search term is in quotes. For a single word, no quotation marks are needed. To respond to you, my search was ACLM/”quantum computing” AND AN/”International Business Machines” — USPTO response was 47 patents; for ACLM/”quantum computing” AND AN/Google, the USPTO response was 9 patents; and for the same search structure but for Microsoft, the USPTO response was 38 patents. I tried AN/China, but the USPTO response was 0. The #s are current as of 11/16/2021.

For you and others, when there’s a USPTO response that’s non-zero, the patents are listed by the patent number and they’re in numerical order.

3. To Kyle Swanton: I searched for AN/IonQ, and the USPTO response was 16 patents.

4. To Model 101: Please see my response to Comment #6 by Anon.

5. To Murphy Lin: I think your question raises only the ACLM field code for “claims.” For ACLM/”quantum communication” => 117 patents. For ACLM/”quantum sensing” => 1 (# 11,165,505). For ACLM/”silicon photonics” =>228 patents. For ACLM/”fusion energy” => 36 patents. For ACLM/LiDAR => 4,207 patents. For ACLM/metalens => 21 patents. For ACLM/metasurface: 182 patents.

6. To Anon and also Model 101: ACLM/”generic computer” => 30 patents. They too are listed by patent number and are in numerical order. If you click on each number and open the patent, “generic computer” should be in boldface and you may well find different contexts for the phrase, as used by the different inventors.

Nick Brestoff

November 22, 2021 02:29 pm1. To Mark G: I tried the links and saw that you searched for “quantum computing” in the title OR abstract OR claim in a different database, which was unfamiliar and not the United States Patent Full-Text and Image Database, Advanced (“USPTO”). However, the responses you may have received did not show up, so ???

2. To Max Drei: (a) For patents issued on or before 11/16/2021, I searched the USPTO using ACLM/”quantum computing” and AN/”International Business Machines” => 47 patents. I then searched for ACLM/”quantum computing” and AN/Google => 9patents. Last, I searched for ACLM/”quantum computing” and AN/Microsoft => 37 patents.

Here (and below): ACLM is the field code/acronym for Claims. and AN is the code for Assignee. Also, for each search, the patent numbers appear in the results.

3. To Kyle Swanton: I search AN/IonQ => 16 patents.

4. To Model 101: See my response in #6 to Anon.

5. To Murphy Lin: I searched for ACLM/”quantum sensing” => 117 patents; ACLM/”quantum sensing” => 1 patent, No. 11,165,505; ACLM/”silicon photonics” => 228 patents; ACLM/”fusion energy” => 36 patents; ACLM/”LiDAR” => 4,207 patents; ACLM/metalens => 21 patents; and ACLM/metasurface = 182 patents.

6. To Anon and Model 101, I search the USPTO for ACLM/”generic computer” => 30 patents. If you repeat this search, you’ll find 30 patents numbers and “generic computer” in the claims. If you open each patent, you should be able to read how the inventor used the term of interest.

Anon

November 22, 2021 10:46 amModel 101,

I am curious as to if you (or anyone) has ever seen an exacting physical description of this so-called thing of a generic computer.

Murphy Lin

November 21, 2021 11:12 pmHow about these trends of patent’s number for another emerging technologies like quantum communication, quantum sensing, silicon-photonics, fusion energy, LiDAR, metalens or metasurface?

Model 101

November 21, 2021 12:22 pmAnother generic computer.

Kyle Swanton

November 21, 2021 10:00 amI saw that IonQ did not make your list. From what I read they are doing pretty well.

IonQ Happens to be the first pure play quantum computing company to go public. Their principal actors have a long history in research and development of quantum computing. This makes me doubly curious as to why they are not mentioned in your article. I am fascinated with the field and would love to learn anything new about the players who will bring quantum computing to the every day aspects of the world we live in. Who will be the players that bring quantum hardware and software from the labs of universities into the fabrication factories and software development company’s of the world?

MaxDrei

November 21, 2021 10:00 amOf the 150 patents that will issue in 2021, how many of them belong to IBM + Google + MS and how many to enterprises in China (who are of course in less of a rush to issue Press Releases)?

Any information on that.

Mark G

November 21, 2021 06:05 amA helpful analysis of USPTO patents. While USPTO fillings are comprehensive, a more complete global analysis of “quantum computing” patents is available here:

https://link.lens.org/P7D7sZxWtif

and a broader search on the quantum computing technology here: https://link.lens.org/EcO37c8ulec