“In most countries in Asia, any color-based trademark application will, for sure, at least at the first round, be rejected on the grounds of lacking distinctiveness.”

With their creative minds, marketing and advertising folks never disappoint in coming up with brilliant ways to distinguish their goods and services from the competition – for example, Tiffany’s robin’s egg blue and Hermes’ orange. This type of marketing genius allows one to immediately recognize a brand without even seeing the word “Hermes” or knowing how to pronounce it. On the flip side, these ideas are prime targets for copycats. After all, by simply changing the jewelry box color to the exact pantone shade of Tiffany’s turquoise blue, a seller could immediately quadruple his/her revenue by profiting from consumer confusion without having to increase the inventory quality or spend a dime on marketing. The question then is: is it possible to protect a color (or color combination) in all jurisdictions by registering it as a trademark?

With their creative minds, marketing and advertising folks never disappoint in coming up with brilliant ways to distinguish their goods and services from the competition – for example, Tiffany’s robin’s egg blue and Hermes’ orange. This type of marketing genius allows one to immediately recognize a brand without even seeing the word “Hermes” or knowing how to pronounce it. On the flip side, these ideas are prime targets for copycats. After all, by simply changing the jewelry box color to the exact pantone shade of Tiffany’s turquoise blue, a seller could immediately quadruple his/her revenue by profiting from consumer confusion without having to increase the inventory quality or spend a dime on marketing. The question then is: is it possible to protect a color (or color combination) in all jurisdictions by registering it as a trademark?

In the United States, the answer is yes – one can and is most likely able to register a single color as a trademark so long as there’s sufficient commercial use and consumer recognition to support the color as a source identifier for the underlying products or services. For example, the owners for the following marks have proved sufficient “acquired distinctiveness” and all of the below colors have been allowed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to be registered as trademarks:

- The ‘robin’s-egg blue’ or, more commonly known as, ‘the Tiffany blue’, for fragrance products, jewelry, watches, and tableware (Tiffany);

- Red soles for women’s designer high heels (Louboutin);

- Brown exterior on trucks for courier services (UPS);

- The famous and highly coveted red knobs on kitchen appliances (Wolf) from cooktops and toaster ovens to outdoor barbeque grills.

These colors carry legal significance as trademarks, allowing the owners to claim exclusive rights to use such colors when it comes to the underlying registered products (or services). In other words, the power of a trademark registration provides a monopoly – as such, no one from Canal Street in New York to downtown Los Angeles is permitted to sell diamond rings, necklaces, or earrings wrapped in the same shade of blue as that of a Tiffany’s jewelry box.

Unfortunately, things are not so easy in Asia.

China

China flatly rejects any trademark applications if the applications are comprised of one single color. The Chinese National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) believes granting such a single color as a trademark would give the owner too much power that could disrupt the market. So, if a trademark application includes one single color – regardless of how unique it is, or if consumers can immediately shout out the brand by taking a quick glance at the color – all such applications will be rejected.

The acquired distinctiveness argument available in the United States will not work in China – except for one rare case, which will be discussed below. This unfortunately opens the back door to opportunistic sellers, allowing them to paint the same red knobs on their cooktops and grills, for example, and pass them on to consumers under the illusion that such products are of the same high-quality as those from Wolf. There are ways to address these issues in China, but unfortunately trademark infringement is not the answer that will give you the home run.

Trademark applications with two or more color combinations (Article 8 of the China Trademark Law) may have a chance – but only a slim one. The rejection from CNIPA is almost guaranteed on the grounds of lacking distinctiveness. The path to registration remains daunting – and expensive – because one will not only need to show a significant amount of use evidence in China but will also need to show that consumers can immediately rely on the color as a source identifier for the underlying goods and services. Although one may argue this is the same level of “acquired distinctiveness” as under the U.S. standard, from experience, we think the threshold requirement is in fact higher because the type of evidence that’s required is almost at the same level to prove a brand as “well-known” in China. As such, although many brands can certainly prove their commercial distinctiveness, they are not able to meet the “legal” threshold of a famous mark. So, although color combinations are allowed to become registered as trademarks in China, many have tried, but most have failed. By contrast, in the United States, certain color combinations might be registered without proof of acquired distinctiveness.

Despite the above, here’s the glimmer of hope if anyone still wants to try and push for a trademark registration. The famous Christian Louboutin high heels caused quite a wave in China a couple of years ago. Essentially, the shoemaker was aggressively pushing for trademark registration for a single-color red, positioned on the bottom of the shoe. CNIPA rejected it twice, citing Article 8 of the Trademark Law, which makes it clear that a single color is not allowed to become a registered trademark. Christian Louboutin pressed on, initiating multiple court appeals. Surprisingly, although the Beijing court is known for its unwillingness to overturn a CNIPA’s decision, particularly on issues relating to what can or cannot be a trademark, the first instance, second instance and even the Supreme People’s Court sided with Christian Louboutin. The reason? Christian Louboutin provided sufficient evidence relating to secondary meaning and, accordingly, the color was allowed to become a registered trademark despite the black and white language of the law.

Below is a screenshot of the famous red-shoe registration in China:

Unfortunately, although Christian Louboutin offers some hope that Chinese examiners and judges may be relying on the same secondary meaning standard as their peers in the United States, this is an exception of the most extreme kind. Despite this precedent, CNIPA has made it clear that no trademark will be approved for registration, at least during the review stage within its office, so long as it’s composed of one single color.

Japan and Korea

The trademark laws in these countries are less rigid than China but still not as accommodating as the United States. The good news is the law allows a single-color application to be registered as a trademark. The unsurprising bad news is the Japan Patent Office (JPO) has yet to grant one.

Under the JPO Trademark Examination Guidelines, “a trademark composed of a single color or of two or more colors will invariably be treated inherently devoid of any distinctive character, and the trademark applicant will then be required to prove the acquired distinctiveness of such trademark through use.” These guidelines are remarkably similar to U.S. law (except the fact that acquired distinctiveness is not always required for color combination marks in the United States), but their application in practice appears to be different, given the lack of success registering single colors in Japan. The difference lies in the threshold requirement to prove distinctiveness in Asia vs. the US; the former is a lot more stringent than the latter.

In most countries in Asia, any color-based trademark application will, for sure, at least at the first round, be rejected on the grounds of lacking distinctiveness. The local law requires the applicant to show that the mark has acquired secondary meaning and has obtained a high level of fame, locally. In other words, general international use or fame evidence is not enough. So, for example, even though U.S. consumers can immediately recognize the Wolf-branded kitchen appliances by the red knobs, such red knobs mean little to consumers in Japan because of the size of their kitchens, which typically only allows for a two-burner stove cook top as opposed to the four or six burners commonly seen in American households. So, no matter how much fame evidence Wolf is able to supply from the U.S. and western markets, it will be of little help to push for registration for its color mark in Japan.

The type of evidence that’s given the most weight is traditionally financial evidence, such as sales volume, market share, or advertising expenditures. All of these need to be supported by objective third party materials, such as newspaper/magazine articles and receipts from advertising agencies and the corresponding annual reports.

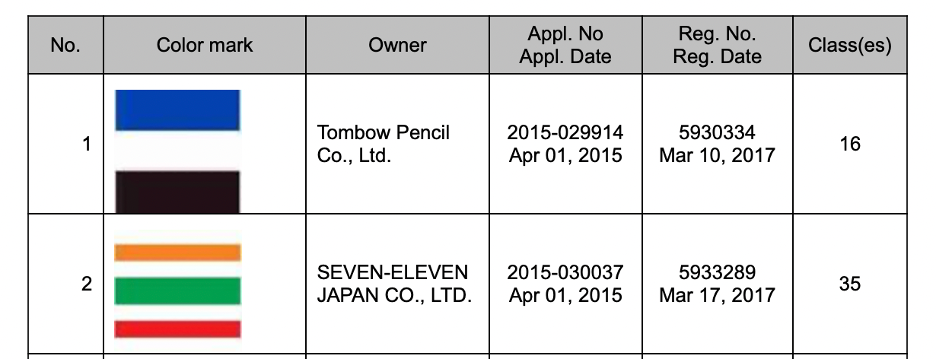

So, the famous gold-green-red color scheme of 7-Eleven stores is registered as a trademark in Japan; same with the blue-white-black mark for the Mono erasers many kids in Asia use in school. In both cases, even though the color has long become exclusively associated with the underlying services (convenience stores) and products (erasers) for decades – in fact, generations – each applicant still had to go through multiple interviews with the examiner and submit an enormous amount of evidence before their marks were awarded registration status.

Below are trademark registration details in Japan about the famous eraser (Mark 1) and 7-11 color registration (Mark 2).

Takeaways

Although sufficient consumer recognition is likely enough to help a color become a registered trademark in the United States, Asia is a different story. The Asian countries covered above may allow a single-color or a color combination mark to become registered as a trademark, but the path to registration is extremely difficult (and expensive) because the type of evidence that’s required is similar to that which is required to prove a mark as legally “well-known” in Asia. Unless the color combination has been in use in the local market for at least three years and has obtained a popularity level similar to that of 7-Eleven convenience stores in Asia, there’s little value in trying to register the color/color combination as a trademark. Therefore, when a brand is newly launched, even though there may be an impressive amount of press coverage and the associated social media posts may have gone viral from Paris to Tokyo, any trademark application in Asia seeking to register the color – or color combination – is most likely to fail.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: pedro2009

Image ID: 8096538

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.