“We view Yale’s standard as sound law, ensuring that an obviously errant disclosure of a typographical or similar nature would not prevent a true inventor of the claimed subject matter from later obtaining patent protection.” – CAFC

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) earlier today held in a precedential decision that a typographical error in a prior art document would have been dismissed by a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA) and thus could not be used to prove obviousness. The appeal was brought by LG Electronics, Inc, against ImmerVision, Inc. and related to claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,844,990 for “capturing and displaying digital panoramic images.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) earlier today held in a precedential decision that a typographical error in a prior art document would have been dismissed by a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA) and thus could not be used to prove obviousness. The appeal was brought by LG Electronics, Inc, against ImmerVision, Inc. and related to claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,844,990 for “capturing and displaying digital panoramic images.”

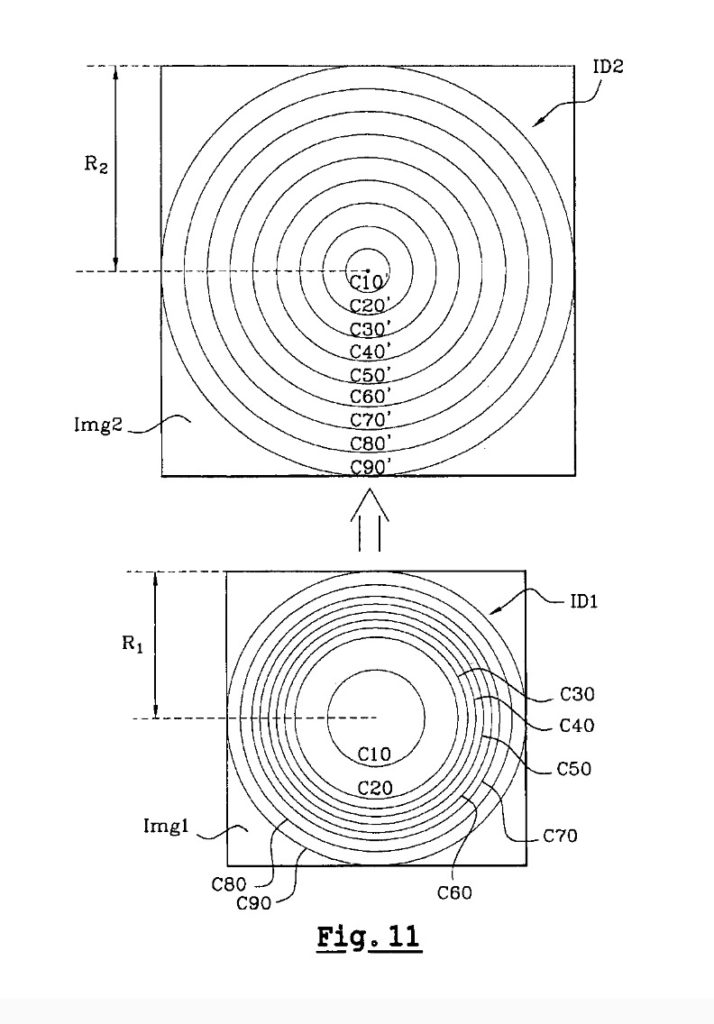

LG petitioned the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) to institute inter partes review (IPR) on two dependent claims of the ‘990 patent in two separate petitions. LG relied on U.S. Patent No. 5,861,999 (“Tada”), directed to a “Super Wide Angle Lens System Using an Aspherical Lens. LG enlisted an expert to reconstruct the lens described in Figure 11 of Tada using the information in Table 5 of Tada, who ultimately declared that “Tada’s third embodiment has a distribution function producing ‘a compressed center and edges of the image and an expanded intermediate zone of the image between the center and the edges of the image’ as recited in challenged claims 5 and 21.”

The PTAB instituted review and ImmerVision’s expert explained that this result was due to “a readily apparent error that cannot form the basis of any obviousness ground.” ImmerVision’s expert, David Aikens, replicated the model used by LG’s expert but soon found the image was distorted and could not make a usable image. He soon determined that “the aspheric coefficients from Table 3, which corresponds to Tada’s Embodiment 2, “were exactly the same as in Table 5,” which corresponds to Embodiment 3.” The CAFC explained:

“It became clear to Mr. Aikens that, after ‘chang[ing] the aspheric coefficients [of his model] to match’ those of the Japanese Priority Application, the aspheric coefficients in the Japanese Priority Application were the correct ones and that they yielded a lens surface that was ‘a perfect match to the surface described in Table 6.’ J.A. 3042 (Aikens Decl. ¶¶ 74–75). In other words, there was a transcription, or copy-and-paste, error in Tada. The disclosures in Tada’s Table 5, which were intended to correspond to its Embodiment 3, were actually identical to those in Table 3, which corresponded to Embodiment 2.”

The PTAB agreed with Aikens and held that the “’disclosure of aspheric[] coefficients in Table 5 of Tada is an obvious error’ that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have recognized and corrected.” Further, since “the correct aspheric coefficients in Table 5 of the Japanese Priority Application do not satisfy the language of the challenged claims,” LG had not proven the claims unpatentable as obvious.

In re Yale

In its discussion, the CAFC explained that the key question before it was “whether substantial evidence supports the Board’s fact finding that the error would have been apparent to a person of ordinary skill in the art such that the person would have disregarded the disclosure or corrected the error.” The court relied on In re Yale, decided by the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (CCPA), the predecessor to the CAFC, in 1970. In that case, an obvious typographical error in a prior art reference (an article) led to the errant disclosure of a compound that was not known at the time. The CCPA held there that:

“[W]here a prior art reference includes an obvious error of a typographical or similar nature that would be apparent to one of ordinary skill in the art who would mentally disregard the errant information as a misprint or mentally substitute it for the correct information, the errant information cannot be said to disclose subject matter.”

The CAFC said “we view Yale’s standard as sound law, ensuring that an obviously errant disclosure of a typographical or similar nature would not prevent a true inventor of the claimed subject matter from later obtaining patent protection.” The court also found the Board’s fact finding to be supported by substantial evidence.

A Distinction Without a Difference

LG presented two additional arguments: 1) that Yale imposed an “Immediately Disregard or Correct” standard that was not met here and 2) that Yale applies only to purely typographical errors. The CAFC rejected both of these, explaining first that Yale imposed no temporal requirement and, while the amount of time it took Aikens to discover the error could be relevant to the analysis, it is just one factor to consider overall and did not negate the Board’s finding “that Tada’s disclosure of aspheric coefficients in Table 5 is an obvious error of a typographical or similar nature, notwithstanding the amount of time that preceded detection of the obvious error.” Secondly, although the error in this case was not identical to the type of error made in Yale, and instead was “a transcription error . . . namely, inadvertent duplication of the values for the aspherical data in Table 3,” it amounted to “a distinction without a difference.”

Newman Disagrees

Judge Pauline Newman dissented in part because she did not agree that the error was “typographical or similar in nature,” noting that “its existence was not discovered until an expert witness conducted a dozen hours of experimentation and calculation.” While a typographical error is readily apparent and may be ignored by a reader without impact, here, patent attorneys, examiners or the two instituting panels of the PTAB. Newman explained that while she agreed Yale sets the correct standard, she did not agree with the way the majority applied Yale to the facts of this case:

“An ‘obvious error’ should be apparent on its face and should not require the conduct of experiments or a search for possibly conflicting information to determine whether error exists. When a reference contains an erroneous teaching, its value as prior art must be determined.

The error in the Tada reference is plainly not a ‘typographical or similar error,’ for the error is not apparent on its face, and the correct information is not readily evident. It should not be necessary to search for a foreign document in a foreign language to determine whether there is an inconsistency in a United States patent. The foundation of the ‘typographical or similar’ standard is that the error is readily recognized as an error. I am concerned that we are unsettling long-standing law, and thus I respectfully dissent in part.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

B

July 13, 2022 10:04 am@ Anon

100% agreement on everything.

Plus, it seems just entirely unfair to have one’s IP destroyed by a typo

Anon

July 11, 2022 06:58 pmThe notion here is simple: the legal (read that as NOT HUMAN) fiction of the juristic person of Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art is simply not some real person (expert or a contrasted ‘anyone else’) that did not understand the plain fact of a typo – be it in a foreign language or not.

The Legal Fiction is charged with an omniscient level of understanding of what IS the current state of the art, and that state of the art is NOT swayed by mere typos.

The only thing on display here is that even giants like Judge Newman are still (real) human and make mistakes.